In his Gospel John records that on the Sunday morning following Jesus’s crucifixion, Mary Magdalene went to the tomb and, finding it empty, started to weep, for she thought someone had taken the body. In her worry and frustration, she “turned around and saw Jesus standing, but she did not know that it was Jesus . . . supposing him to be the gardener” (John 20:14–15). It isn’t until he says her name that she recognizes him.

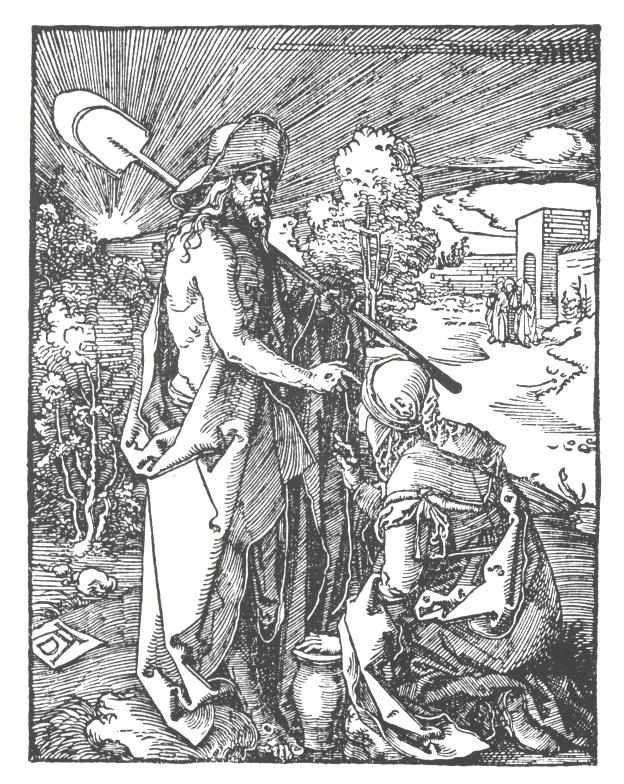

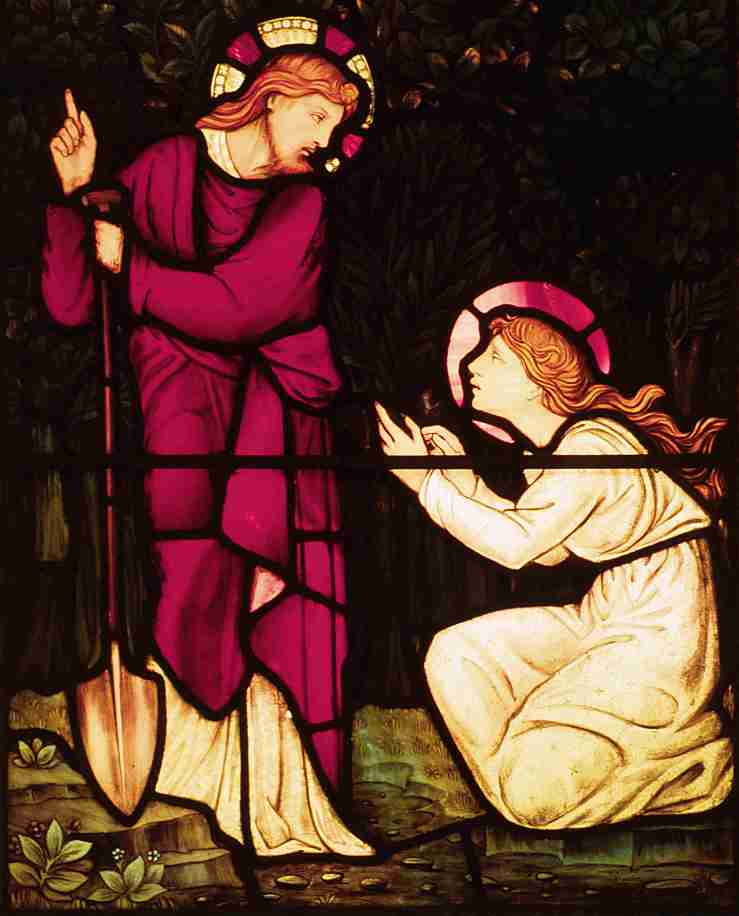

Artists—mainly from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries—have latched onto this detail of mistaken identity, representing Jesus carrying gardening tools, like a shovel or a hoe, and sometimes sporting a floppy gardener’s hat. A few artists, such as Lavinia Fontana, Rembrandt, and the illuminators of the book of hours and passional shown below, have even shown Jesus in full-out gardener’s getup. (In her commentary on John, Dr. Jo-Ann A. Brant mentions that the fact that Jesus left his burial clothes in the tomb, coupled with Mary’s confusion, might provoke the “fanciful speculation” that Jesus actually borrowed the gardener’s clothes. Nevertheless, a different understanding is more likely behind the artistic representations; read on.)

The portrayal of Jesus as a gardener isn’t meant to suggest that Jesus was literally gardening that day—though he might have been, and that’s amusing to think of. Rather, it alludes to his role as one who “plants” us and grows us. He gets his hands dirty in the soil of our hearts, bringing us to life and cultivating us with care so that we flourish.

According to Franco Mormando, whose research involves the religious sources of Renaissance and Baroque Catholic art, Jesus the gardener was a traditional theme of orthodox scriptural exegesis and popular preaching whose origins can be traced back to patristic times. In a 2009 article for America magazine, he writes,

Mary’s misidentification was meant to remind us, so the pre-modern exegetes taught, of a spiritual reality: Jesus is the gardener of the human soul, eradicating evil, noxious vegetation and planting, as St. Gregory the Great says, “the flourishing seeds of virtue.” Although today out of circulation, this teaching was disseminated [in the fourteenth through eighteenth centuries] in such popular, authoritative texts as Ludolph of Saxony’s Life of Christ (a book that played a crucial role in St. Ignatius Loyola’s conversion) and [starting in the seventeenth century] Jesuit Cornelius a Lapide’s Great Commentary on Scripture.

The Bible makes explicit the connection between God the Father and gardening. Genesis 2:8 tells us he was the world’s first gardener: “And the Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east, and there he put the man whom he had formed.” The prophets sometimes wrote of God’s gardening in a metaphoric sense—for example, in Isaiah 61:11: “For as the earth brings forth its sprouts, / and as a garden causes what is sown in it to sprout up, / so the Lord God will cause righteousness and praise / to sprout up before all the nations.” Or Jeremiah 24:6, in which God says of the exiles from Judah, “I will build them up, and not tear them down; I will plant them, and not pluck them up.” Furthermore, Jesus’s parable from John 15 casts God as a vinedresser.

John’s Gospel, though, goes even further to ascribe this role to Jesus, and to present his resurrection as the genesis of something new. For example, the prologue to his Gospel starts, “In the beginning . . . ,” an obvious echo of the prologue to Genesis. In 19:41 he mentions that Jesus was buried in a garden, and in chapter 20, that he was found walking around in it. He mentions twice that Jesus rose on “the first day” of the week, as if this were the first day of a new creation (cf. Genesis 1:3–5). And then he has Mary mistake Jesus for the gardener. When taken in concert with Paul’s conception of Jesus as the Second Adam (Romans 5:12–21; 1 Corinthians 15:21–22, 45), these allusions suggest that Jesus is the gardener of the new Eden, doing what Adam could not do. His resurrection broke ground in this garden, marking the beginning of a massive restoration project.

That’s why Jesus is so often found toting a shovel in the resurrection art of Renaissance and Baroque Europe. He is the caretaker of humanity, bending down to bring us up, to make us full and healthy and beautiful. Charles Spurgeon preached a sermon on the topic back in 1882, in which he declares,

Behold, the church is Christ’s Eden, watered by the river of life, and so fertilized that all manner of fruits are brought forth unto God; and he, our second Adam, walks in this spiritual Eden to dress it and to keep it; and so by a type we see that we are right in “supposing him to be the gardener.”

More recently, Andrew Hudgins—inspired by the imagination of visual artists—wrote a poem called “Christ as a Gardener.” You can read it in full here.

I’m curious to know whether any modern artists have exegeted John’s text in the same way—that is, portraying Jesus as a gardener in his appearance to Mary Magdalene. Besides a pen, brush, and chalk work by Anton Kern, done in a Baroque style, I am aware of only a few, the first of which is Graham Sutherland’s 1961 altarpiece in the St. Mary Magdalene Chapel of Chichester Cathedral. Commissioned by Walter Hussey, one of the twentieth century’s most important patrons of sacred art, Graham Sutherland painted two versions of Noli me tangere. Hussey chose the one that shows a door opening out into a garden and Christ wearing a sun hat made of straw, pictured below. (Click here to see a wider shot of the painting in its chapel context.) The alternate version is in the Pallant House Gallery, also in Chichester.

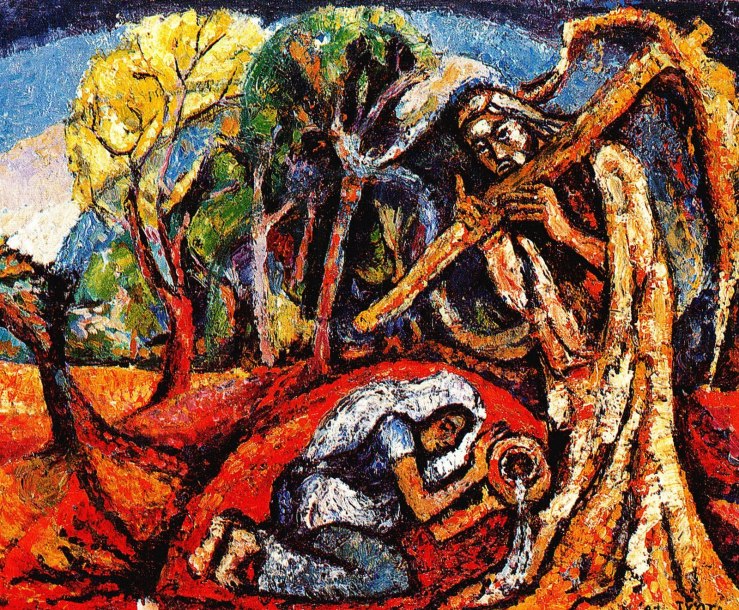

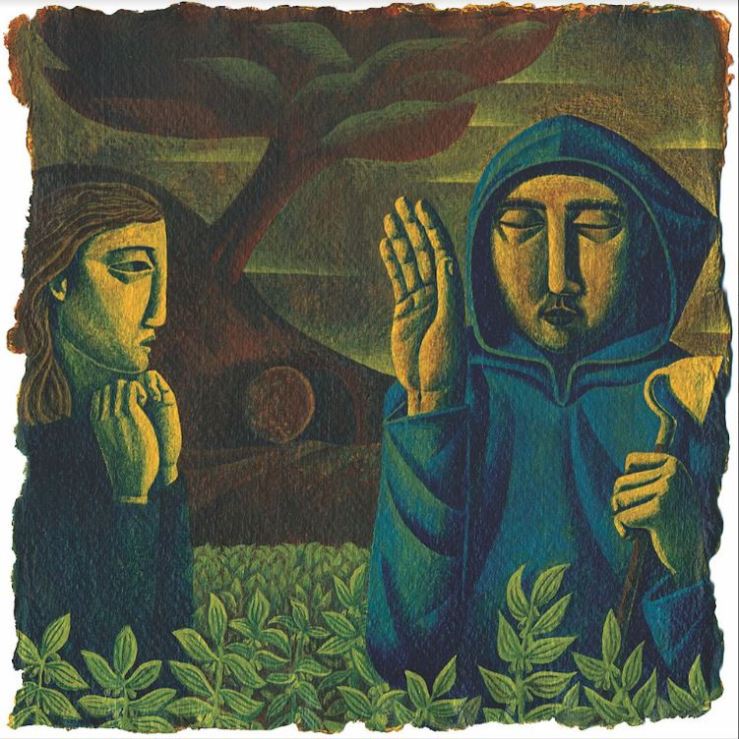

Back in 2010 Jyoti Sahi posted an oil painting on his blog along with three others under the heading “The Resurrection.” I think the signature says 1987, but it’s hard to tell, as it’s cut off in the photo. In it Jesus carries an oversize scythe while Mary anoints his feet, just as she had done a week earlier, when she had shed tears in anticipation of his death (John 12:1–8). The outline around her is reminiscent of a kernel of wheat.

Most people associate scythe-wielding figures in art with the Grim Reaper—that is, Death—due to an iconography that stretches all the way back to the fourteenth century. But the Bible associates scythes with Jesus, the lord of the harvest (Matthew 3:12; Matthew 13:24–30; Revelation 14:14–20), the harvest being the end of the world. Only those who have rejected Jesus need fear his Second Coming, for those who have grown in his word will be gathered up into heaven. This painting in particular reminds me of Psalm 126:5: “They that sow in tears shall reap in joy”—a beautiful song of ascents that has been set to music by, among others, Bifrost Arts. Mary had wept along Christ’s road to Calvary and again at his grave, but now, because of his Resurrection, she enters into his presence with shouts of joy.

Lastly, He Qi’s Do Not Hold On to Me from 2013 also references the Jesus-as-gardener metaphor, but because the head of the implement Jesus holds is in shadow, it’s not as obvious.

Do you know of any artworks from recent times that take on this theme?

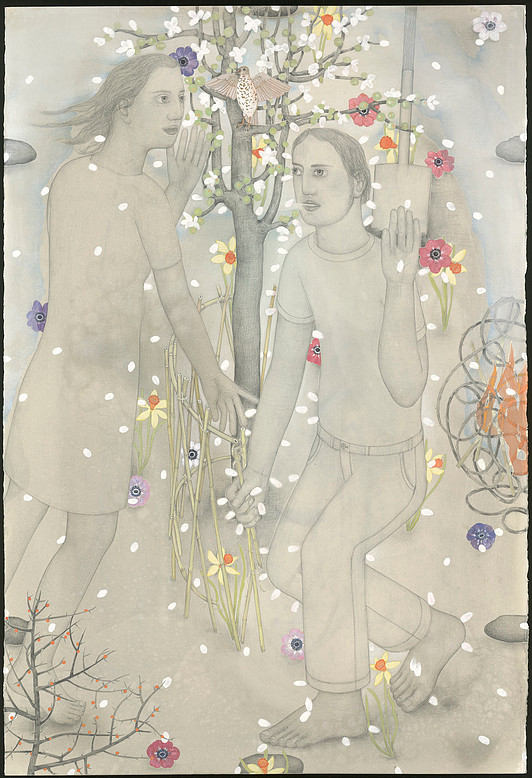

Update, August 1, 2019: I found a few more! Jesus as gardener is actually a favorite theme of Dutch artist Janpeter Muilwijk. His 2017 painting New Gardener shows the freshly risen Christ in a white T-shirt and overalls, heading with open arms toward Mary, who is dressed like a bride to receive him. (Mary is modeled after the artist’s daughter Mattia, who died; see “Walking the Via Dolorosa through Amsterdam, part 2.”) Butterflies alight on each of Jesus’s five wounds, marking them as sites of transformation, and the flowering branches of a tree crown him with spring glory.

In an earlier gouache, Muilwijk shows Jesus removing the protective fencing from around the tree of life, welcoming Mary in. Both are showered by white flower petals. His breath is visible; he speaks her name. She brushes his arm lightly with her pinkie finger. In the background a garden shovel is propped up in a heap of soil, indicating the breaking of new ground.

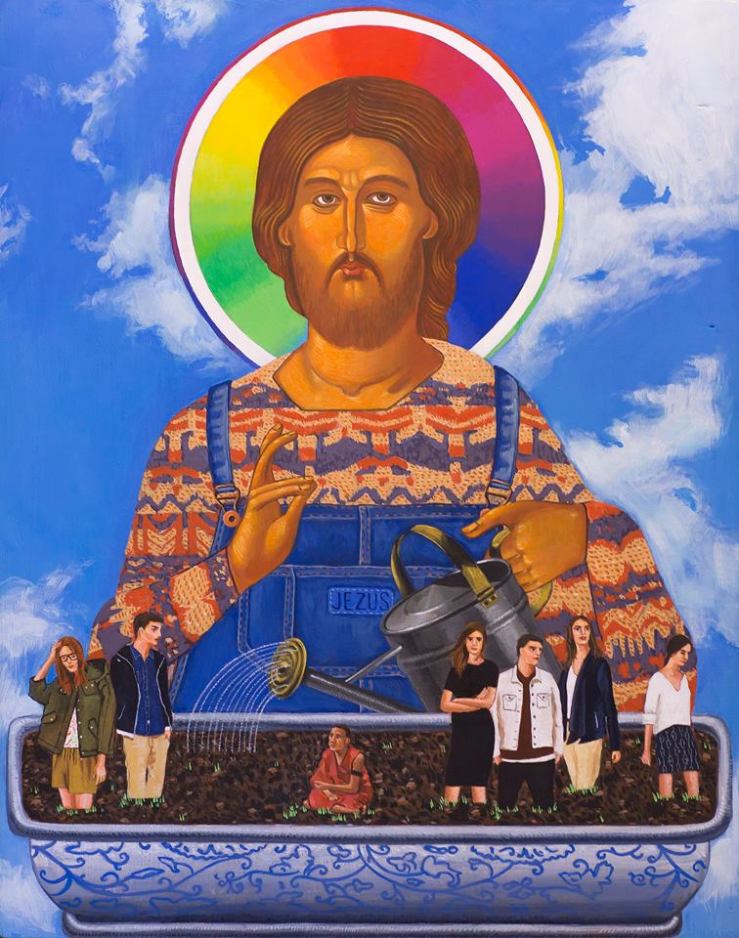

Włodzimierz Kohut’s Jesus the Good Gardener visualizes the gardener metaphor with humor. It shows a Byzantine-style Jesus with a rainbow halo, wearing a hipster sweater and overalls with his name (in Polish) sewn onto the front pocket. With his right hand he blesses, and with his other he holds a watering can. He lovingly waters the “seedlings” in his ceramic planter: that is, human beings in modern dress. They stand knee-deep in the soil in various attitudes, some eagerly awaiting their growth, others resisting it.

Update, February 1, 2022: And the imagery keeps coming! The Gardener by Joel Briggs shows an olive-wreathed Christ bringing new life to a devastated landscape, the wounds of crucifixion still borne in his wrists and lower side. With one hand he holds a shovel over his shoulder—a dove perched on its handle—and with the other he holds a nascent olive tree, its leafy sprigs peeking out from a clod of dirt.

The artist says, “I need a Lord and Savior who is redeeming me in my humanness. Who is bringing new order to the old chaos, new life to the old, worn-out wastelands. Christ is not erasing the human story. His coup de grâce against the curse upon humanity is not the removal of my humanity. His final triumph is undying humanity—his physical resurrection, in which human thriving is defined. . . . The seemingly fragile and infantile promise of the inheritance of all creation is being held in the firm grasp of he who is both gardener and ‘first of the fruit’ of his garden.” Follow Joel Briggs @joelbriggspaints.

Very interesting. I’d never heard the typography of Christ as gardener of the New Creation (at least not in any way I can remember, and certainly not linking to Mary Magdalene’s mistaking him post-resurrection). As I was scrolling through the pictures, all I could think of was how silly Jesus looks wearing a floppy sun hat. But as soon as you introduce the typography, I think I appreciate it a lot more. I think one of the beautiful things about iconography is how there is the ability to depict things not necessarily as they appear, but as they actually are. One might say that Mary Magdalene indeed saw Christ as He truly is (even though she did not recognize Him), as the true Gardener.

LikeLike

[…] ukjent, han er også en som hun gjenkjenner, det er Jesus Kristus, både fremmed og fortrolig. ”Noli me tangere” (”rør meg ikke”), svarer han bryskt. Er denne advarselen en allusjon til ordene Moses […]

LikeLike

Excellent article. Thank you for the research that has been put into this. So glad I found this. God bless you.

LikeLike

Thank you for this article and the research you has been put to it. I am planning on reblogging it. I have to say though that Western Art’s depiction of Christ is too worldly in my opinion.

LikeLike

Thank you for the interesting article. I like Francesco de Mura’s version of “Noli Me Tangere” –Jesus is carrying a hoe and looks startlingly corporeal for one who is on the way to ascending; as in many representations of this scene, there’s an interesting tension between earth and heaven, between the earthly and the spiritual. I just saw an exhibit of de Mura’s work at the Chazen Gallery in Madison, WI, and I found a black-and-white representation online and this art poster of “Noli Me Tangere.” http://www.art.com/products/p22103777997-sa-i7498563/francesco-de-mura-noli-me-tangere-c-1750.htm?ac=true

LikeLike

In1979, our daughter Ellyn was a student at St. Leonard’s School, St. Andrews, Scotland. Among her schoolmates were female members of the Royal Family, including Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, namesake of the then Queen Mother. She invited her school friends (and Ellyn’s visiting parents) home “for tea.” Home turned out to be Glamis Castle (where Macbeth killed King Duncan). On a tour of the Castle, we were taken to the private chapel, where a series of biblical scenes adorn the walls. Painted by the 17th century Dutch limner Jan de Wet, one depicts Jesus and Mary Magdalene at the empty tomb–and we understand immediately why she failed to recognize him at first: He looks exactly like a Dutch burgher tending to his garden, wearing a large black hat and leaning on a shovel.

I have written about this in my book THE TIMELESS MOMENT: CREATIVITY AND THE CHRISTIAN FAITH, pp.120-121. I have not been able to find a reproduction of the Glamis Castle scenes. D. BRUCE LOCKERBIE

LikeLike

[…] Easter 2016 I published an article on Jesus as the gardener of our souls, featuring a roundup of Noli me tangere (“Touch me not”) paintings that portray the risen […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

thank you for all the images – saw both Sutherland paintings yesterday in Chichester and was well confused that there appeared to be two identical paintings – so I was just looking that up and came across this lovely blog!! I see now the hat which just goes to show, I should always be looking more closely! Actually for the cathedral visit I mostly wanted to see the Chagall window but in the event, the Sutherland painting is the one thing I can’t get out of my mind.

LikeLike

I’ve just listened this week to an episode of Richard Rohr’s podcast, Another Name for Everything, which presents a wonderful contemplation on Mary’s “garden moment” with the risen Christ – highly recommended! It’s from Season 1, Episode 9 and this link should get you there: https://centerforactionandcontemplation.podbean.com/e/9-peter-paul-mary-minus-peter/

LikeLike

[…] “‘She mistook him for the gardener’”: Humanity was born in a garden and reborn in a garden, as biblical scholars like N. T. Wright are keen to point out, with Easter morning marking the launch of new creation. In art history the resurrected Christ is sometimes amusingly shown carrying gardening tools when he encounters Mary Magdalene outside his tomb—to explain the case of mistaken identity, perhaps, but more likely to establish a metaphor. Two of the paintings I’ve added to this post are by Janpeter Muilwijk, whose New Gardener from 2017 shows the freshly risen Christ in a white T-shirt and overalls, heading with open arms toward Mary, who is dressed like a bride to receive him. (Mary is modeled after the artist’s daughter Mattia, who died.) Butterflies alight on each of Jesus’s five wounds, marking them as sites of transformation, and the flowering branches of a tree crown him with spring glory. […]

LikeLike

[…] So there are two stereotypes here and now, which I present as “mostly” accurate in pointing to deeper truths, but which at the same time must give way to greater truths, only captured satisfactorily for me in an icon. First we take up the fact that men are physically stronger than women. As we already said, this cannot equate to a moral right to physical force against women. What are we to take it as? We must make of this an icon, the icon of Christ the New Adam, the Gardener of the New Eden. […]

LikeLike

[…] (For more artwork of Jesus as gardener visit She Mistook him for the Gardener.) […]

LikeLike

Hello Everyone,

This lovely aspect of the Resurrection Story also needs to be cross + referenced with the mention of flowers, roses in particular and the garden in Edward FitzGerald’s world famous Mystical Masterpiece The Ruba’iya’t of Omar Khayya’m being a unique painting in words of our Universal Story from Alpha to Omega… “Beauty will save the world” Dostoyevsky

LikeLike

Great subject

You missed Holbein’s work, a cracker.

Yes the real meaning of this Bible story is do not take it literally.

Simple as that.

All religious texts are fiction, but not necessarily less worthy for that.

Can still lead down therapeutic paths.

So here Do not touch means do not waste your effort because it’s not touchable.

And the Gardener is neat too. Powerful allegory.

Because we are all gardeners in our own individual ways, and collectively through our communities, societies..

Means it’s up to us here on spaceship Earth to grow something useful, to take care of the Earth too.

LikeLike

In the esoteric traditions Christ comes first in the physical…the mineral level then next ( second coming) in the etheric…the time body life organisation…thats one stage up… the plant realm…sp she is seeing his next incarnation of sorts prefired in the guise of a gardener…

As mentioned this is an esoteric view which in my experience many artists work out of…make of it what you will.

LikeLike

[…] the middle of a garden. Which may help explain the long tradition of depicting Jesus as a gardener. In this article by Victoria Emily Jones (which I highly recommend browsing through), I learned that paintings from the European Renaissance […]

LikeLike

[…] the middle of a garden. Which may help explain the long tradition of depicting Jesus as a gardener. In this article by Victoria Emily Jones (which I highly recommend browsing through), I learned that paintings from the European Renaissance […]

LikeLike

This is such an excellent compilation, and the writing is beautiful. What a sweet story God has crafted and brought us into. Thanks for sharing this.

LikeLike

[…] Grace impaled.That you might nowbe just a flashof something likea past’s passed past.“A garden now,”as Herbert said,“is what becomesof Gospel […]

LikeLike

[…] Guite’s “Jesus dies on the cross,” part of his Stations of the Cross sonnet cycle, was inspired by a line from George Herbert’s poem “Prayer”: “God’s breath in man returning to his birth.” And his “Easter Dawn” [previously] is based in part on a sermon by the seventeenth-century Anglican bishop Lancelot Andrewes. Paraphrasing Andrewes, Malcolm says, “Jesus is the gardener of Mary [Magdalene]’s heart—her heart is all rent and brown and wintery, and with one word, he makes all green again.” Beautiful! For more on the theme of Jesus as gardener, see my 2016 blog post “She mistook him for the gardener.” […]

LikeLike