The wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the young goat, and the calf and the lion and the fattened calf together; and a little child shall lead them. The cow and the bear shall graze; their young shall lie down together; and the lion shall eat straw like the ox. The nursing child shall play over the hole of the cobra, and the weaned child shall put his hand on the adder’s den. They shall not hurt or destroy in all my holy mountain; for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord as the waters cover the sea.

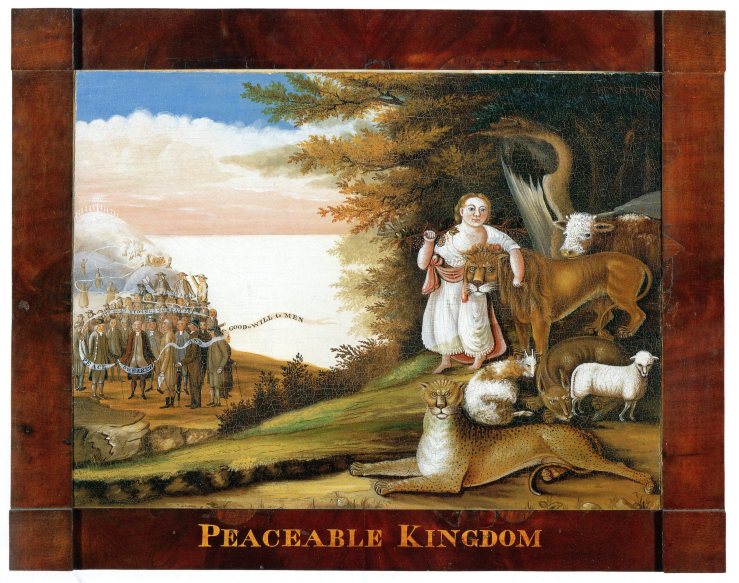

This passage describing the peaceable kingdom of the Messiah was, according to biblical scholar John F. A. Sawyer, popularized by the Quaker preacher-artist Edward Hicks, born in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, in 1780. He painted it sixty-two times during his career: predators and prey lying down together in harmony, and a little rosy-cheeked child—the Christ child—leading them.

When Edward was just eighteen months old, his mother died. His father was unable to support him financially, so he sent him to board with family friends David and Elizabeth Twining, who exposed him to Quakerism. From ages thirteen to twenty Edward lived with local coach maker William Tomlinson, for whom he worked as an apprentice, developing a talent for ornamental painting. When his apprenticeship ended in 1800, he went into business for himself, now painting with decorative motifs not only carriages but also signs, furniture, and household objects. Some of his signboard compositions would later prompt commissions for easel paintings.

During this time Edward was attending religious meetings with increasing regularity, becoming an official member of the Society of Friends in 1803. But he encountered criticism from many of his fellow Friends for his choice of vocation, which was at odds with the Quaker values of simplicity and utility. Painting is a worldly indulgence, they said. Taking their rebukes to heart, Edward gave up painting for a time and tried his hand at farming, but this venture was unsuccessful.

Edward struggled to reconcile his love of painting with his faith; he was passionate about both. In 1811, at age thirty-one, he set up a painting shop in Newtown, Pennsylvania, and also became a minister, which meant that he was often called away to other states to preach. Quaker ministers were not paid for their services, so it was necessary for Edward to maintain a source of income to support his wife and four (soon to be five) children.

“Of all the types of paintings Edward produced during his lifetime, none was repeated as often or with greater attention to change and refinement than the Kingdom pictures,” writes Carolyn J. Weekly in The Kingdoms of Edward Hicks, the catalog for the major exhibition she organized in 1999 for the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in Williamsburg, Virginia. Edward pursued this subject not for commercial reasons (records suggest that he gave the Kingdom paintings as gifts to friends and family) but to express his yearning for unity and peace, especially in light of the 1827 Hicksite-Orthodox schism within the Society of Friends, the first in the denomination’s history. (Edward’s cousin Elias led the liberal faction that split from the mainstream.) His Kingdom paintings reference the schism through a blasted tree trunk, which doubles also as a reference to the “stump” of Jesse out of which Christ sprung up (Isaiah 11:1).

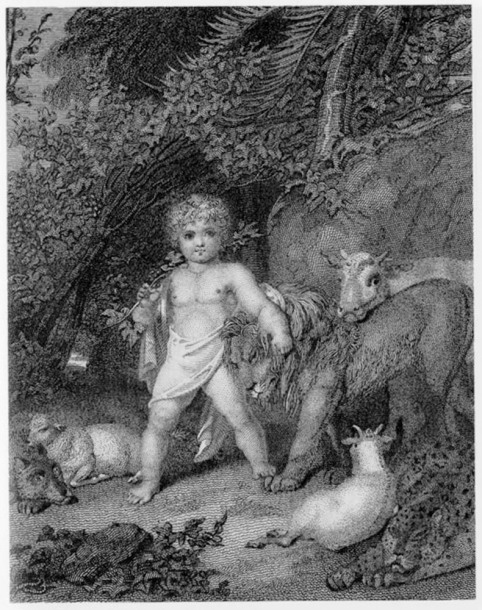

Only a few Peaceable Kingdom images before Hicks’s time have been documented worldwide, among them an early nineteenth-century engraving designed by Richard Westall. Hicks borrowed directly from Westall in his “Peaceable Kingdom of the Branch” compositions, replacing the Christ child’s loincloth with a little jumper suit fashionable among Friends at the time.

The Branch paintings are referred to as such because they show a child holding a grapevine, an allusion to both the fruit-bearing branch of the Tree of Jesse from Isaiah 11:1 and the blood of Christ that we partake of at the Lord’s Supper.

Around the border of several of his paintings, like the one pictured above from Mead Art Museum, Edward painted a rhyming paraphrase of Isaiah, taken from a contemporaneous prayer-book:

The wolf shall with the lambkin dwell in peace,

His grim carniv’rous nature then shall cease;

The leopard with the harmless kid lay down,

And not one savage beast be seen to frown;

The lion and the calf shall forward move,

A little child shall lead them on in love;

When man is moved and led by sovereign grace,

To seek that state of everlasting peace.

In others he changed the verb tense of this rhyme from future to past and substituted the following final couplet:

When the great Penn his famous treaty made

With Indian chiefs beneath the elm tree’s shade.

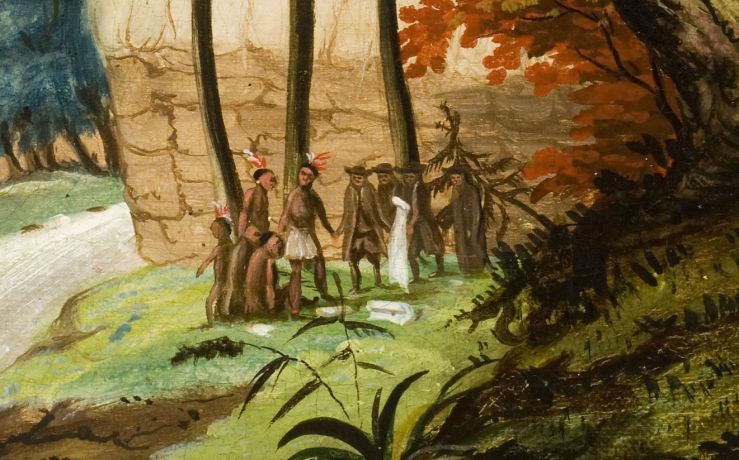

Edward represented this episode from America’s colonial past—Pennsylvania founder William Penn signing a treaty of perpetual friendship with the Lenape Indians in 1681 (some sources have 1682 or 1683) on the banks of the Delaware River—in many of his Kingdom paintings, sometimes prominently and sometimes as a minor detail. This, Edward thought, is what it looks like to put into practice the values of brotherly love and peace that Christ came to teach us. Penn did honor this treaty, but his successors did not—a fact that Edward was painfully aware of.

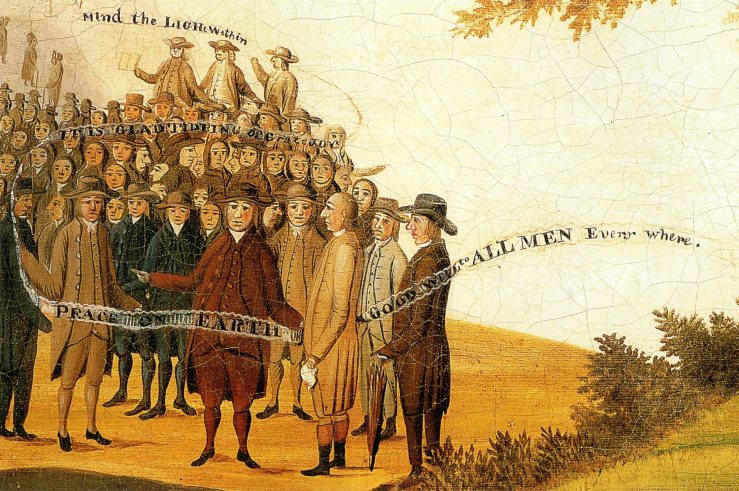

In place of this vignette, Edward sometimes depicted instead a congregation of leading Quaker figures unfurling a banner that paraphrases the angels’ announcement to the shepherds of the birth of Christ: peace on earth, goodwill to men (Luke 2:14). And often the directive “Mind the light within,” a reference to the Quaker doctrine of the inward light (Christ himself), which indwells believers, giving them a direct and personal experience of God. There are nine extant “Banner Kingdoms.”

Although Edward was initially hopeful about mankind’s ability to establish peace on earth by simply exercising biblical principles, over time he became more and more cynical, an attitude that’s reflected in his work. While his early Kingdom paintings from the 1820s show animals in joyful company with one another, the animals in many of his middle- and late-period paintings are tense or exhausted, or even bare their teeth in open hostility. In some—such as the Yale University one above, but even more noticeably in the one from the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum (detail below)—Christ’s hold on the lion’s mane is one of forcible restraint rather than gentle guidance.

Hicks wrote later in life that all the intrafaith dissension he witnessed had destroyed his hope of ever seeing established in the here and now a kingdom like the one Isaiah envisioned. But that realization only caused him to cling to Christ all the more tightly.

At first glance the Kingdom paintings may seem naive, but actually they are the artist’s attempt to tease out the tension between “peace on earth” and the violence and divisiveness of man. The Quaker experiment had failed, but still Edward harks back to it as a consideration of what could have been, had not man’s warring nature gotten in the way. (Edward elaborates on people’s animal qualities in his Goose Creek sermon of February 22, 1837, the most important source for interpreting the Kingdom paintings, says Carolyn Weekly.)

As a way to enter further into the “peace” theme of the second week of Advent, I presented one of Edward’s Kingdom paintings, in digital projection, to my church congregation this past Sunday, closing with this charge:

Today we live between the two advents of Christ. The Prince of Peace has come as a little child to tame our wild hearts, but somehow peace still seems so elusive. Edward Hicks wrestled constantly with the tension between the already and not-yet aspects of Christ’s kingdom, and we are called to do the same. So let us look back to the manger birth and forward to the eschaton, meanwhile living in the light of him whose law is love, and whose gospel is peace.

Update, December 2018: I’ve written and narrated a short video on Edward Hicks’s Peaceable Kingdom for art historian James Romaine’s Art for Advent video series. Check it out!

This essay is an expanded version of the “Coming as peace on earth” section of the booklet Come, Lord Jesus, Come: Visual Devotions for Advent, available for free download.

[…] reproduced in black and white—for example, Motley’s Tongues (Holy Rollers), Edward Hicks’s Peaceable Kingdom, and Lawrence’s Sermon II and Sermon VII. Luckily these can be found online, but seeing as the […]

LikeLike

[…] channel next week for subsequent videos. For more on Hicks and this favorite subject of his, see this post of mine from 2016. Thank you to Rain for Roots for letting me use their wonderfully playful musical […]

LikeLike

[…] The images used in this manuscript are downloaded from https://artandtheology.org/2016/12/06/the-peaceable-kingdoms-of-edward-hicks/ or the websites this page links […]

LikeLike

[…] The Peaceable Kingdoms of Edward Hicks at Art and Theology – blog by Victoria Emily Jones […]

LikeLike

[…] wallpaper on my computer desktop is a version of the painting The Peaceable Kingdom by Edward Hicks. It’s a fascinating painting with a powerful story behind it. There are 62 […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting information, indeed. Thank you!

LikeLike

[…] (Related post: “The Peaceable Kingdoms of Edward Hicks”) […]

LikeLike

Are there any original artwork by Edward hicks in australia.Could you please let me know as I have seen a very old painting of his.

LikeLike

I’m not sure.

LikeLike

[…] https://artandtheology.org/2016/12/06/the-peaceable-kingdoms-of-edward-hicks/ […]

LikeLike

[…] by Edward Hicks (1780-1849), an American painter. You can find background information on this piece here and Hicks’ bio […]

LikeLike

[…] https://artandtheology.org/2016/12/06/the-peaceable-kingdoms-of-edward-hicks/ – Victoria Emily Jones […]

LikeLike

[…] [1] For more about Hick’s and his paintings, see https://artandtheology.org/2016/12/06/the-peaceable-kingdoms-of-edward-hicks/ […]

LikeLike