Last summer when participating in a two-week Calvin College seminar, I was providentially assigned to room with Margaret (Peggy) Adams Parker, a sculptor and printmaker who lives, as it so happens, just an hour south of me! Peggy’s enthusiasm—for God, for life, for art—is infectious. She possesses such deep joy, and yet she feels so deeply the hurts of the world. She is attentive, as all good artists must be. “I feel called as an artist to bear witness to the world I see around me and also to the ways I understand that world,” Peggy wrote in an ArtWay feature. “This yields not only images of beauty and tenderness, but also images of suffering and terror.” She regards her art as a means of prayer.

The recipient of numerous church and seminary commissions, Peggy majors on religious and social justice themes. Her sculpture Mary as Prophet won a 2016 honor award from the Interfaith Forum on Religion, Art, and Architecture. In addition to maintaining a studio practice and doing shows, Peggy serves as an adjunct instructor at Virginia Theological Seminary, teaching such courses as “Encountering Scripture through the Visual Arts” and “The Artist as Theologian.” She also writes for various publications, including ARTS: The Arts in Religious and Theological Studies and the Anglican Theological Review, and collaborated on the book project Who Are You, My Daughter? Reading Ruth through Image and Text. She is currently working on a Saint Andrew sculpture group. To learn more about Peggy and view more of her work, visit her website, www.margaretadamsparker.com.

By way of further introduction, here is an essay Peggy wrote ten years ago for the book Heaven, ed. Roger Ferlo (New York: Seabury Books, 2007), pp. 158–66. It is reproduced by kind permission of the publisher.

“Where Sorrow and Pain Are No More”

by Margaret Adams Parker

To be honest, I’ve never thought much about heaven, at least in any systematic fashion. I was interested enough to pick up, at some point, The Great Divorce, C. S. Lewis’s allegory of heaven and hell. And I’ve been known to joke about my expectations that heaven had better have a comprehensively stocked art studio, as well as a fabulous bookstore.

But in looking back though many years of making art and also teaching about art at a Christian seminary, I’ve unearthed a great deal about heaven, although not in the expected places. I haven’t glimpsed heaven among the many imagined depictions, ranging from medieval woodcuts to the visual speculations of twentieth-century outsider artists. I’m simply not drawn to “visionary” images. These are not the kinds of images I make. Instead, my image of heaven is distinctly negative (theologians would call it apophatic). I have no vision of what heaven is like. But I have seen, and I have also made, pictures of what heaven is not.

I am a concrete thinker, and so my art is earthbound, far from visionary. I’ve always understood the incarnational nature of Christianity as a charge to take seriously life in this world. What’s more, my two great artistic mentors—Rembrandt and Käthe Kollwitz—were rarely given to visions. Rather, their work was grounded in the physical, spiritual, and social realities of life. Such symbols as they used (most notably Kollwitz’s use of the skeleton to represent death) served to underscore their understanding of human existence as it is. They recorded moments as small as a child learning to walk and as momentous as war or revolution. Even when picturing the incarnation, that most heavenly of earthly events, both artists showed the miracle taking place in a tangible human setting.

Consider some of these two artists’ characteristic images. Rembrandt’s drawings testify powerfully to his all-encompassing interest in the life around him. He depicted everyone he saw—beggars and merchants, rabbis and serving girls—with the same probing yet sympathetic scrutiny. His drawings of his wife Saskia constitute a particularly poignant record: we watch as she endures four pregnancies, suffers the deaths of three infants, and finally dies at thirty, a short nine years after their betrothal. We glimpse her first in a silverpoint drawing (1633), made the week of their engagement. In this love poem in line, Rembrandt shows us a winsome young woman, resting her cheek lightly against her hand, dangling in her other hand one of the flowers that also adorn her straw hat. In a pen and ink drawing made four years later (1637), Saskia lies in bed, supporting her head heavily on her hand, staring out with a weary and resigned expression. And in the image that Rembrandt sketched on a tiny etching plate the year Saskia died (1642), she has become an old woman, worn, gaunt, and desperately ill.

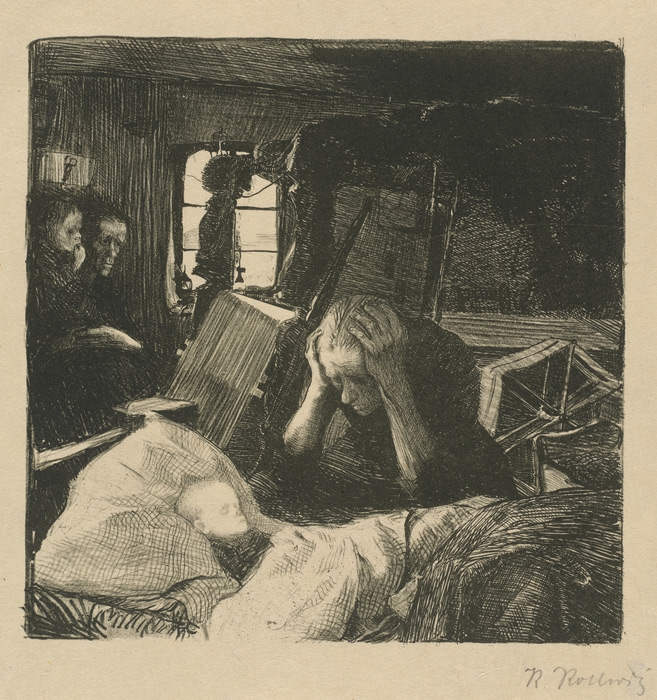

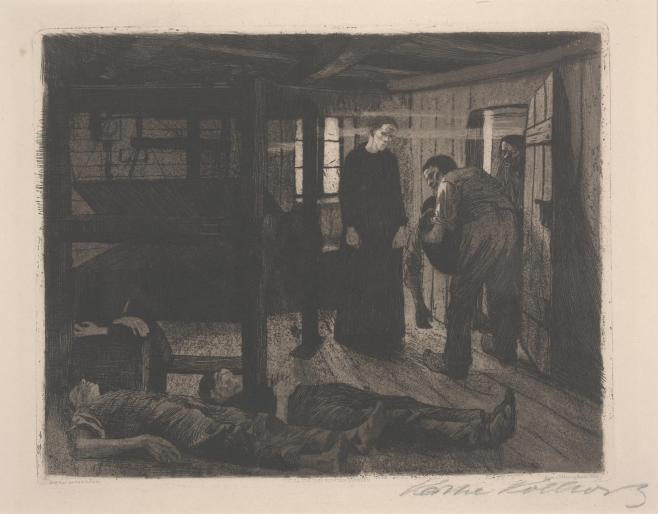

Käthe Kollwitz’s imagery is more politically engaged. The daughter of a trained lawyer who chose to work as a builder rather than practice within the Prussian legal system, she spent her life depicting the plight of the poor and protesting the ravages of war. In her first great print series, A Weavers’ Rebellion (1897–98), she chronicled the causes, progression, and bloody aftermath of the 1844 revolt of Silesian home weavers against their employers. The series begins with Poverty (1894), where a family of weavers gathers around the deathbed of an infant, and concludes with The End (1897), where the bodies of slain revolutionaries are being laid out on the floor of a weaver’s cabin. In both of these dimly lit interiors, the looms and other apparatus of the weavers’ trade stand as ominous reminders of the weavers’ plight.

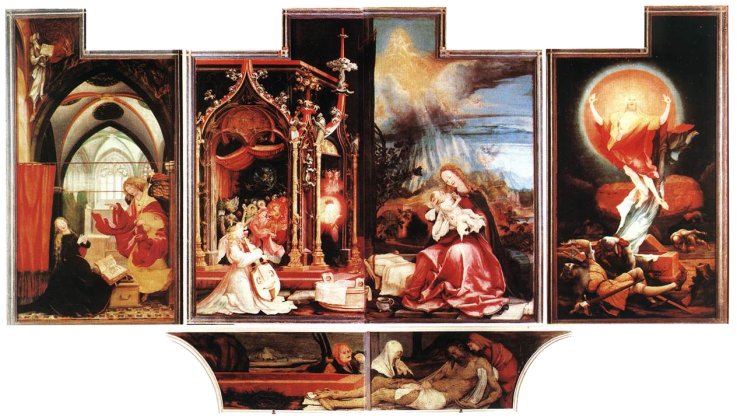

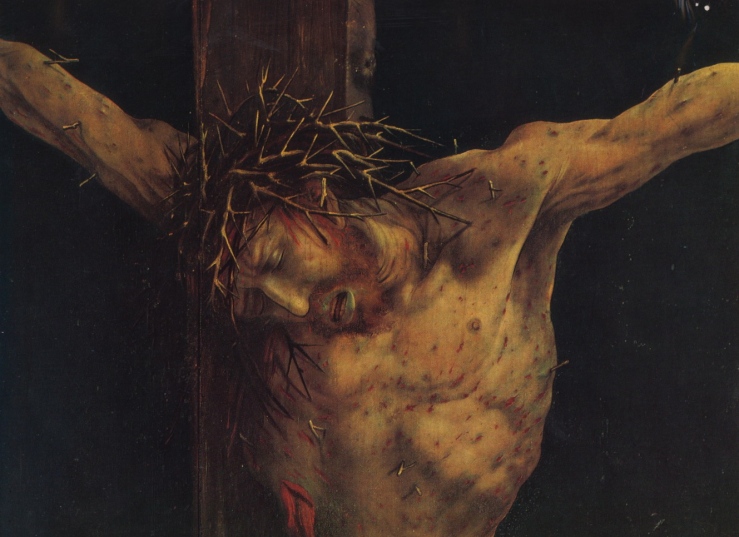

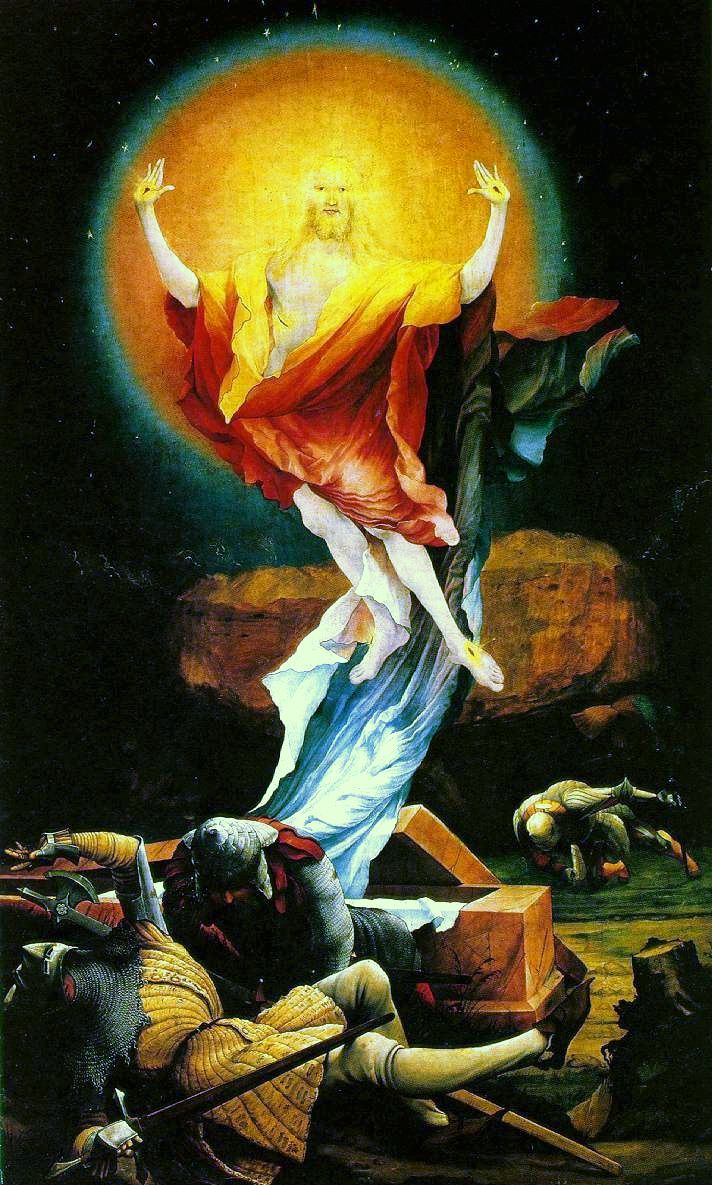

I would never have thought to link any of these earthly images with heaven until I recalled Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1511). This enormous altarpiece—eleven feet high, almost twenty feet wide, and constructed in three separate layers of images—manages to be simultaneously earthbound and visionary. It contains the most graphic of crucifixions and the most hallucinatory of resurrections. The altarpiece was created for a hospice in Isenheim, Germany, where members of the Antonine order treated victims of ergotism (called St. Anthony’s fire). The condition resulted from eating bread made with ergot-infected barley. The disease was characterized by burning lesions, treated with amputations as limbs became gangrenous, and resulted, inevitably, in death.

While there was no cure for the disease, those suffering from it must have found comfort in viewing the great altarpiece, which was opened and closed to reveal different images on different days. On weekdays viewers would have seen the outermost layer, depicting the Crucifixion. Grünewald’s crucified Christ is a graphic image of torment, his flesh a sickly green and marked with lesions and thorns, his hands and feet twisted in agony. On Sundays, Christmas, Easter, and other feast days, the outer layer was opened to reveal the second layer, picturing Annunciation, Incarnation, and Resurrection. The contrast between Christ of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection is arresting. The suffering Christ has barely enough energy to draw breath; the risen Christ is joyfully, triumphantly alive. Surging with energy, he raises his arms and spreads them wide to display the wounds in his hands. All five wounds radiate beams of light. Moreover, Christ’s hair is washed clean and golden, his garments are shining and new, and his figure is posed against a glowing nimbus, blue on the outer edge, turning to red, and glowing golden in the center, just behind his head. But to those suffering from ergotism, the most significant feature of this image would have been Christ’s flesh, which appears whole and sound, cleansed of every blemish and wound.

I have looked at this Resurrection countless times with my students, yet my first response is always the same: it seems unbearably psychedelic. (I am reminded of the posters from my college years of rock stars in DayGlo colors.) But when I remember the context, and think of the sufferers who gazed on this image, I am always moved. To the victims of ergotism, the Crucifixion was a reminder that God suffered with them, for them; the Resurrection showed them what heaven would be like: not just a place where their sins might be forgiven but where their suffering bodies would be healed and made whole. I still don’t like this image, and I don’t think I will ever respond instinctively to any such vision. But the contrast between Grünewald’s Crucifixion and his Resurrection enables me to understand that the earthbound image can teach us about heaven simply by showing us what heaven is not.

Heaven has to be a place where political repression and the casualties of war are healed. Think of Goya’s Third of May, 1808 (1814), or Picasso’s Guernica (1937). Goya’s painting memorializes the executions carried out in Madrid on that day in response to a popular uprising against Napoleon’s army the day before. Goya divided his canvas between the victims on the left and their executioners to the right. The soldiers all stand in the same rigid position, their faces turned away from the viewer, their rifles leveled at the identical angle. By contrast with the anonymous efficiency of the executioners, the victims form a chaotic mass, their fear and despair transparent. The bloody bodies of the dead sprawl in a heap on one side, while from the other side the condemned trudge fearfully out of the dark night toward their fate. Between them kneel the men facing the firing squad. They pray, plead, rant, or cover their faces. The light of a huge lantern focuses attention on one particular peasant in a white shirt. He kneels, an expression of horror on his face, his outstretched arms recalling the crucifixion.

Picasso’s Guernica, arguably the most significant painting of the twentieth century, was painted to protest the bombing of the town of Guernica in 1937, during the Spanish Civil War. The gigantic canvas—almost twelve feet high and twenty-six feet across—is filled with fear, chaos, and confusion. A man with a broken sword in one hand lies prone across the foreground; a woman screams over the dead child in her arms; another searches the wreckage, lamp in hand; another lifts her hands above her head and cries out in fear; a wounded horse shrieks in the center. The absence of color—the painting is limited to black, white, and shades of grey—calls to mind news bulletins from contemporary newspapers and newsreels. The size of the painting and the scale of the figures assault the viewer. Picasso forces us to confront the obscenity of civilian casualties (the destruction that we now describe, disingenuously, as “collateral damage”).

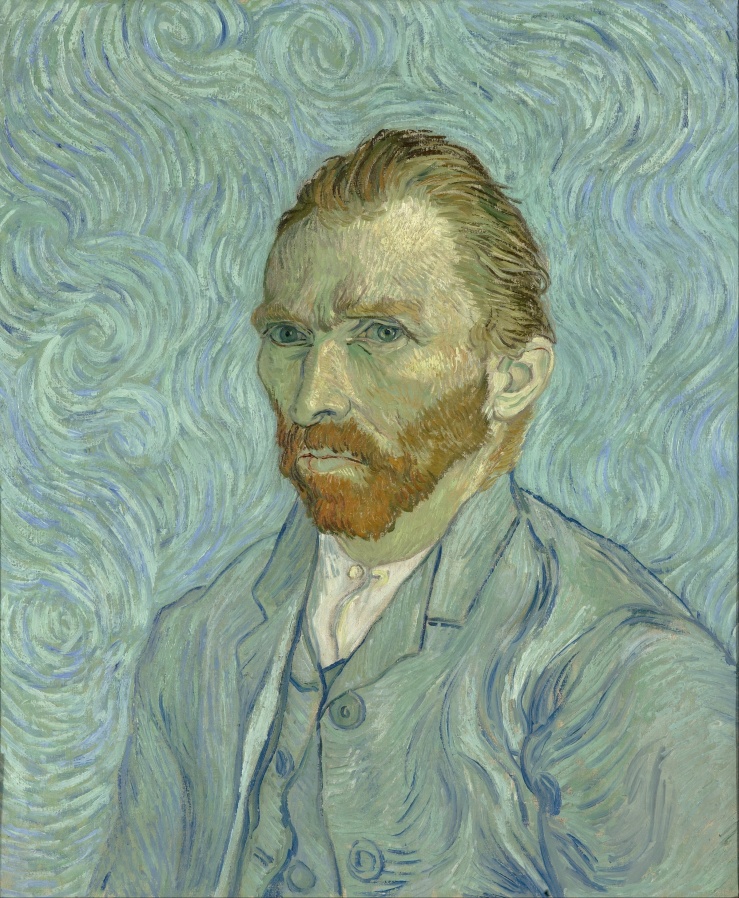

Heaven also heals the more intimate, personal struggles of life. The pain that we see in Rembrandt’s images of Saskia dying will be erased, as will the lifelong experiences of rejection and loneliness that we sense in Vincent van Gogh’s great series of self-portraits. Van Gogh failed in his early ambitions to pastor among the poor. He subsequently channeled his passion and awkward intensity—qualities that so often made him seem frightening to others—into his pursuit of art. His self-portraits (over forty in all) offer painful glimpses into the artist’s restlessness, intensity, and unhappiness. Tellingly, the eyes which confront us in all of these paintings are the same: anxious and piercingly sad. Indeed, in 1890, shortly after van Gogh’s death, his brother Theo wrote about him to their mother, “Life was such a burden to him. . . .” The artist’s own words ten years earlier confirm the immense loneliness conveyed by the self-portraits: “There may be a great fire in our soul, and yet no one ever comes to warm himself at it, and the passers-by see only a wisp of smoke coming through the chimney, and go along their way.” In his final Self-Portrait (1889), painted less than a year before his suicide, turbulent blue brushstrokes dominate the background, move into the blue of his coat and the shadows of his face. His brows are furrowed above glaring blue eyes, his unhappiness palpable in the short, angry strokes that model his face.

Students sometimes ask why artists make such images and why we take time to study them, since the subjects are so unsettling. They wonder why we dwell on these dark aspects of life when we might focus instead on moments of beauty, serenity, or joy. In truth, lament is a significant theme in my own work—although students are usually too tactful to ask the same questions of me—and I suppose this is why I respond so strongly to images I have described. One early lament was a woodcut titled ENOUGH (1996), showing women in various postures of grief. They are silhouetted against a blood-red landscape into which the word “ENOUGH” is carved in a repeating spiral. I created this print in response to the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Itzhak Rabin, who famously declared, “Enough of blood and tears. Enough.” But I resisted for five years the impulse to add Rabin’s words, along with his name, as a subtitle. I didn’t want to limit the meaning of the print to one person or event; there are so many places and times when we urgently need someone to cry, “Enough!” I also wanted to acknowledge the reality that women—who must send sons and brothers and husbands to war, who bear disproportionately the consequences of wars and displacements—are often the ones who initiate the hard work of reconciliation.

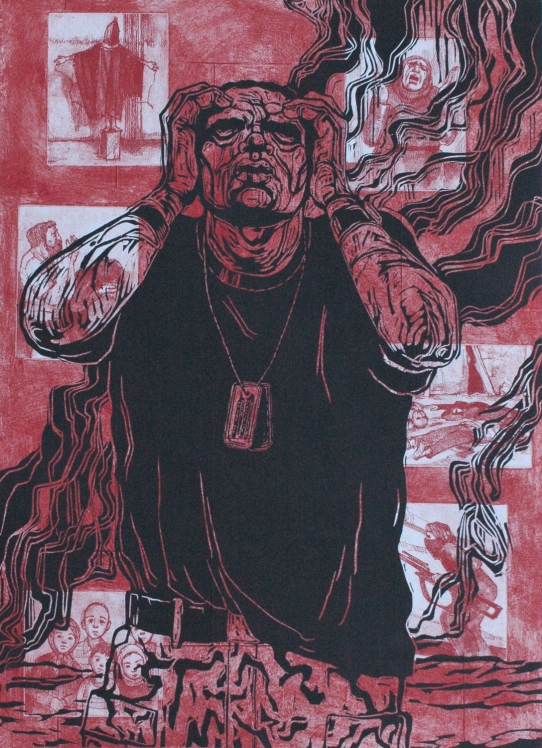

In the intervening years lament has become a recurring theme in my work. Often the impulse to make these images arises spontaneously out of my response to an event in the news: genocide in Rwanda or Darfur, violence in the Middle East, mental instability in soldiers returning from battle in Iraq. It is as though the subject asserts itself, demanding depiction in a woodcut or sculpture. In making each image I strive to enter the experience with my body as well as my heart and mind: I want the gestures of the bodies (as much as the expressions on the faces) to draw viewers into the story. This intense identification with the suffering of others is a form of prayer. And I am gratified when the resulting image, like a psalm of lament, can make visible and real the experience of the sufferer.

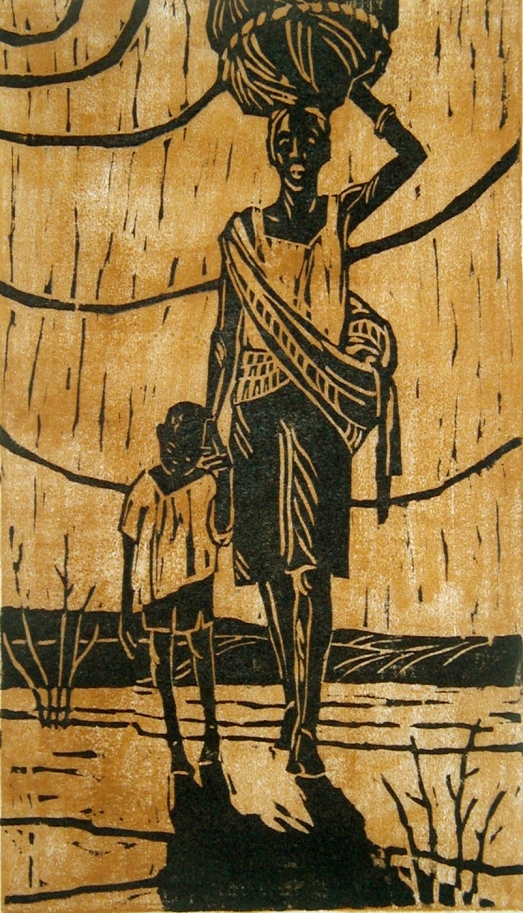

This happened with African Exodus (1997), which I created in response to news descriptions of masses of refugees fleeing genocide in Rwanda. I depicted a lone woman, carrying her possession on her head and leading an exhausted child across a parched landscape. While it seemed presumptuous to speak about this experience out of my comfortable suburban studio, the initial sketch shaped itself on the page virtually unbidden (a rare experience), and I could hardly refuse it. I knew that the woodcut had captured some truth when, in 2001, a student from Southern Sudan chose this print to take home with him, and later, in 2004, when the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees printed the woodcut as the frontispiece to their publication on Refugee Children.

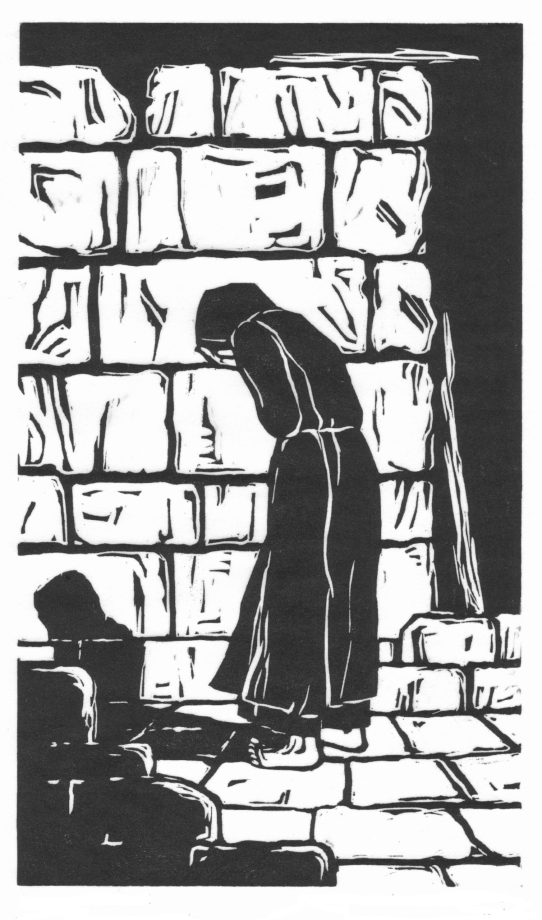

One lament was unexpectedly, horribly prophetic. The image—the final woodcut for an exhibition about Jerusalem—was drawn from the Book of Lamentations. Lamentations 1, “How lonely sits the city that once was full of people. How like a widow has she become . . .” (2001) portrays the personification of the city as a young widow who turns from the viewer, her face hidden in her hands. As I worked, I reflected on the sad reality that these words are as apt in contemporary Jerusalem as they were twenty-six centuries ago. But text and image suddenly took on a terrible new meaning closer to home: the date was September 11, and I was carving this block when I heard, from my studio, the impact of the plane striking the Pentagon.

But lament was not always my theme. Fifteen years ago I was contentedly painting Washington cityscapes and wooded landscapes, searching for the visual poetry of light, shape, and color. Today I still enjoy the beauty of the natural world and I still make prints of fields and streams and trees. But I have discovered that these always take second place when a lament rises out of contemporary events and demands my attention. Right now I have prints in various stages of preparation: sketches of Washington’s cherry trees, the magnificent Dawn Redwood from the Duke Gardens, redwood-lined waterfalls near the Big Sur coastline. But these images are stuck in line behind a woodcut about Iraq and what war does to the soldiers who must fight it.

Friends still ask me why I don’t go back to making those nice cityscapes. Sometimes I wonder myself. But then I am caught up short by reports of the morgues in Iraq filling up with bodies; of dead and wounded soldiers returning to our own country; of southern Lebanon in ruins; of children in northern Israel unable to sleep for fear of incoming missiles; of global warming and environmental destruction degrading the world we are leaving our children. I acknowledge about myself that I am neither a street protester nor a letter writer. I am a maker of images, and this is work I can do to bear witness to these sorrows. In this task I stand on the shoulders of artists long dead and beside artists still working.

In a very fine book, A Theological Approach to Art (1967), Roger Hazleton explains my motivations better than I can: “One does not go to such trouble to portray human brokenness, erosion, or malignancy unless one is deeply concerned with true and whole humanity.” This truly is heaven: a place where humanity, individual by individual, is restored, made true and whole. Deo gratias. It is a place where human brokenness, erosion, and malignancy are healed. In heaven there will be no more war; no more oppression and degradation; no more sin and sorrow and death. In the burial office in The Book of Common Prayer, we recognize these expectations of heaven when we pray:

Give rest, O Christ, to your servants with your saints,

where sorrow and pain are no more,

neither sighing, but life everlasting. (BCP 499)

This brings me back, full circle, to Rembrandt. His etching of The Adoration of the Shepherds, with the Lamp (1654) is always the first work that I show new students. Light radiating from the Christ child illumines Mary’s peasant face, as she lifts her cloak to reveal the infant, and Joseph’s arms, beckoning in welcome. Their gestures draw the wondering shepherds into the light from the darkness outside. Even the shaggy beasts gaze toward the light from the shadows of the barn. The miracle of the incarnation is revealed out of, and by contrast with, the surrounding darkness. It is the same with my vision of heaven: out of the sorrow and suffering of this world I anticipate heaven’s brightness.

As I sit here with a chronic illness, it is so very difficult to look at the PAIN in and of the world and not be able to do anything. What can I do?

LikeLike

[…] Also on display at the exhibit are some of Parker’s small-scale terracotta and plaster sculptures—a few of which I snapped photos of. See her Visitation sculpture here, and her art essay “Where Sorrow and Pain Are No More.” […]

LikeLike

[…] next event is a lecture on April 6, 2019, by printmaker and sculptor Margaret (Peggy) Adams Parker (previously), which I’m really looking forward […]

LikeLike

[…] (Related post: “‘Where Sorrow and Pain Are No More’ by Margaret Adams Parker”) […]

LikeLike