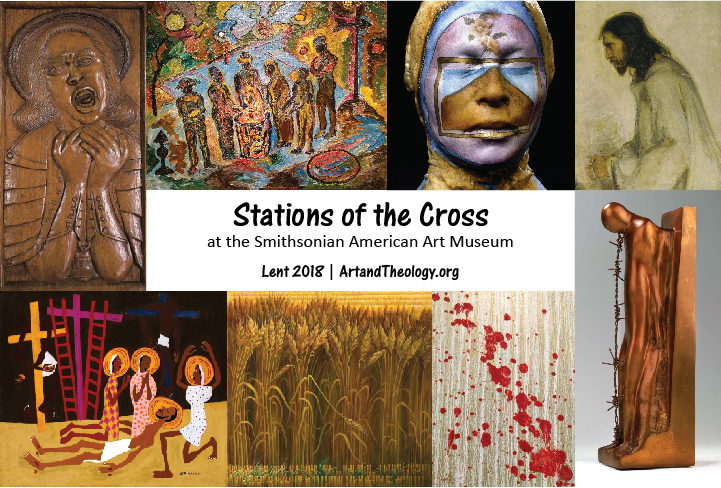

Welcome to the Stations of the Cross audio tour at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), developed by Victoria Emily Jones at ArtandTheology.org.

Originating in the thirteenth century, the Stations of the Cross is a Christian devotional practice whereby participants immerse themselves in the story of Jesus Christ’s final sufferings by metaphorically journeying with him from his trial to his entombment. The road between is known as the Via Dolorosa (“Way of Sorrows”) or Via Crucis (“Way of the Cross”).

In this eighteen-stop tour we will walk this road with Jesus, recognizing along the way the many other paths of sorrow that were traveled in America’s history and that are still being traveled today. Migrant workers, soldiers, prisoners, victims of racial discrimination and violence, the poor and the homeless, the grieving, and the mentally ill are among the many people we will meet through these paintings, sculptures, and mixed-media works that bear witness to human suffering.

The American novelist and social critic James Baldwin said of Beauford Delaney, one of the artists on our tour, “The reality of his seeing caused me to begin to see.” That is my hope: that as we encounter these visual narratives of suffering from our nation’s past and present, we will begin to see. This tour obviously doesn’t cover all the oppressed groups in the US, but this is a starting point for further conversation, discovery, intercessory prayer, confession, and action.

My other hope is that we will be led to a deeper engagement with the biblical narrative—with Jesus’s way of sorrows and why he walked it, what it achieved.

Jesus began his public ministry by reading these words from an Isaiah scroll at his local synagogue at Nazareth:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives

and recovering of sight to the blind,

to set at liberty those who are oppressed,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.

Then, as Luke 4:20–21 tells us, “he rolled up the scroll and gave it back to the attendant and sat down. And the eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. And he began to say to them, ‘Today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.’” This was a very bold move: here, he is claiming to be the messianic servant of the Lord prophesied about in Isaiah 61, who would bring spiritual and, ultimately, material salvation to the world. But the cost of this salvation, the Hebrew prophet tells us, is suffering; the messianic servant must suffer and die. “He was pierced for our transgressions; he was crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace, and with his wounds we are healed” (Isaiah 53:5).

Below you will find eighteen audio tracks of art commentary available for free streaming or download, as well as transcripts and artwork locations. If you are taking this tour virtually, you can click on any of the featured images to jump to that object’s museum page, where you can zoom in on details.

As you walk this Way of Sorrows, beholding the sufferings both of Christ and of those he came to redeem, may these artists’ seeing help you to see.

+++

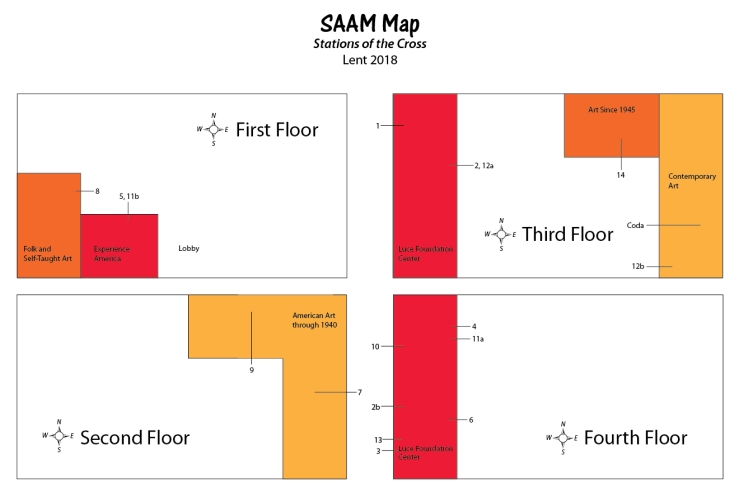

VISITING THE MUSEUM: The SAAM is open daily from 11:30 a.m. to 7 p.m., and admission is free. Its main building is located on the National Mall at 8th Street NW and F Street NW in Washington, DC—conveniently, right next to the Gallery Place–Chinatown Metro stop (on the Green, Red, and Yellow Lines), and within a few blocks of several (paid) parking decks.

Though all these artworks are currently on display, the museum cannot guarantee that that will be the case for the entirety of Lent (in the Luce Foundation Center especially—the museum’s visible storage area—objects tend to move around frequently and unexpectedly). If you notice that any have been temporarily removed, please notify me, and remember that they can still be enjoyed digitally on the SAAM website.

LISTENING OPTIONS: You can stream the audio commentary on this webpage or through the SoundCloud app (available for free download from the iTunes store or Google Play). Free Wi-Fi is available in the Luce Foundation Center, where the majority of tour stops are concentrated, but not in the galleries, so if you prefer to listen offline, you can sign up for a free 7-day trial of SoundCloud Go or download the individual tracks. Be sure to bring your own headphones so that you do not disturb other viewers.

MAPS + PRINTABLE GUIDE: You’ll want to grab an official Visitor Map from the Information Desk in the front lobby to help you get around, but in addition, here is a museum layout marked with the approximate location of each station, followed by a printable guide:

+++

STATION 1. Jesus Is Condemned

[3rd Floor Mezzanine, Luce Foundation Center, 11B]

Commentary (Transcript): The Savior by Henry Ossawa Tanner, ca. 1900–1905

Here at the first station of the cross we meet Jesus at his trial, where he is accused of being a threat to national security. The ravening crowd pronounces his death sentence—“Crucify him! Crucify him!”—and weak-willed Pilate gives in, handing Christ over to be tortured by the state and led to his execution.

In Henry Ossawa Tanner’s painting The Savior, all this commotion is relegated to outside the picture plane, as the focus is put on a silent, haggard, praying Christ, portrayed as an ordinary man of Jewish ancestry. Rendered in loose, expressive brushstrokes, the waist-up profile portrait does not overspiritualize its subject, as religious portraits at the time were wont to do. Instead, Christ’s face is filled with a sense of deep, personal struggle but also raw determination, and his bowed posture underscores both his dejection and his humility. To ground the figure in reality, Tanner uses a restricted palette of mottled browns and beiges, the colors of the earth.

Born in 1859 to a prominent minister in the African Methodist Episcopal church, Tanner was raised in Philadelphia and in 1879 became the first black student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he studied under the progressive painter Thomas Eakins. His work found critical favor, even more so after he moved to Paris in 1891. When Tanner started painting biblical subjects, art critic Rodman Wanamaker financed an all-expenses-paid trip for him to the Middle East so that he could familiarize himself with the people and places he was painting. The Savior is based on one of the sketches Tanner made during this trip.

STATION 2. Jesus Takes Up His Cross

[3rd Floor Mezzanine, Luce Foundation Center, 21B]

Commentary (Transcript): Señor de la Humildad y la Paciencia, 19th century

This small nineteenth-century sculpture from Puerto Rico shows Christ seated on a rock, head in hand, contemplating his impending death. This image type originated in late medieval Europe and is still prevalent in Galicia in northern Spain. There and in other Spanish-speaking countries it is known as el Señor de la Humildad, Lord of Humility; other names for it are the Pensive Christ, Christ in Distress, or Christ on the Cold Stone. In some variations, Christ is shown with a crown of thorns and a scepter, placing it narratively after the mocking and just before the taking up of the cross. The emphasis is on the suffering Christ accepted on our behalf, and the humility and patience with which he bore it.

(Station 2, cont.) [4th Floor, Luce Foundation Center, 36B]

Commentary (Transcript): Look Down That Road by Charles Pollock, 1942

Our second image for station 2 is Look Down That Road by Charles Pollock, the older brother of Jackson Pollock. It shows an African American man in much the same pose as the distressed Christ we just saw, using his suitcase as seat, and he too contemplates the way of sorrow that lies before him. The sense of danger is amplified by the roiling storm clouds, and the man’s psychological discomfort by the knotted, twisted tree.

Where is this man going? Is he moving North to escape racial persecution? Is he on his way to the local draft board to enlist in the war effort? Is he looking for work? Is he leaving family? The title is likely a reference to the folk song “Look Down That Lonesome Road,” in which the speaker laments the heaviness of his load and enjoins others to survey the desolate road ahead before embarking on it.

Pollock painted this image in 1942 during his employment through the Federal Art Project, the visual arts arm of the Depression-era Works Progress Administration. Its style reflects his years as a student of Thomas Hart Benton, whose works, including one at station 9 of our tour, are displayed on the second floor of the museum’s North Wing. It also evinces the inspiration he culled from the Mexican Mural Renaissance. Just a few years later, however, Pollock would abandon social realism in favor of abstract expressionism and color-field painting.

STATION 3. Jesus Falls for the First Time

[4th Floor, Luce Foundation Center, 31A]

Commentary (Transcript): The Breakdown by William H. Johnson, ca. 1940–41

On his way to Calvary, Jesus falls multiple times under the weight of the cross. His collapse is obliquely reflected in The Breakdown by William Henry Johnson, which shows a malfunctioning car, piled high with furniture, stranding a couple in search of a better life. The title refers not just to a mechanical breakdown but to the economic breakdown of American society during the Great Depression, which for some led to breakdowns of other kinds—emotional, spiritual, and/or familial. “I’m broke down” is an expression of despair used especially in blues music.

But the couple in this painting seems to be coping well with their hardship: the wife is improvising a roadside cookfire while the husband works on repairs. Displayed prominently on the car’s hood is a cross ornament, backlit by a sun, alluding to the couple’s sustaining faith and prefiguring the dawning of a new day.

Johnson was a major figure in twentieth-century African American art. Born in South Carolina, he traveled extensively throughout Africa and Europe, living for extended periods in France and Scandinavia. Though he experimented with realism and expressionism, he is best known for the flat, consciously naive style he adopted after his return to the US in 1938, using a palette of only four or five colors. His output during this period depicts African American subjects—farm workers, street musicians, market shoppers, churchgoers, chain gangs, etcetera—sometimes even working them into biblical narratives, as we will see in station 13.

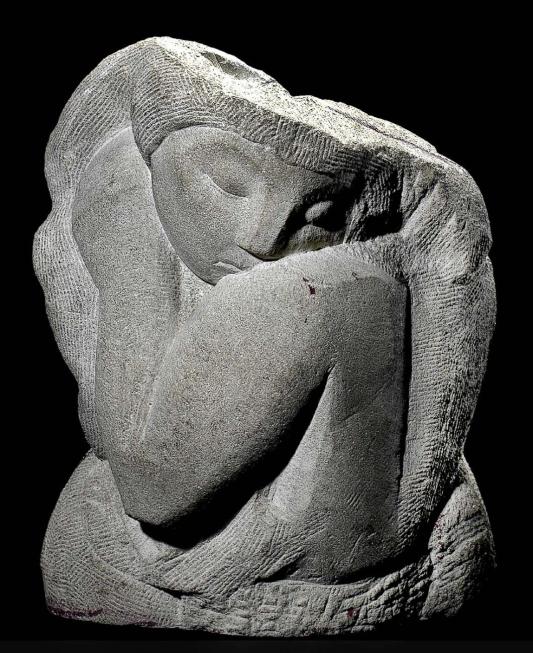

STATION 4. Jesus Meets His Mother, Mary

[4th Floor, Luce Foundation Center, 48A]

Commentary (Transcript): Woman’s Head by Moissaye Marans, n.d.

At the fourth station of the cross, Jesus meets his mother on the roadside. Most artistic representations of this imagined moment show Mary tearfully embracing her son’s broken-down body. Who knows what words they might have exchanged during this, their last encounter before his death.

Woman’s Head by Moissaye Marans doesn’t explicitly depict this cross-station, but the form is evocative of a very tender, maternal embrace. Though the poses aren’t fully fleshed out, we can see the mother’s downcast head, her nose touching the other figure’s shoulder, her arms circling his lower back. With eyes closed, she savors their goodbye.

Marans was a Jewish immigrant from Romania, specializing in biblical subjects. Sometimes referred to as “the sculptor of peace,” he is best known for his fourteen-foot bronze sculpture Swords into Plowshares, which adorns the facade of the Community Church of New York in midtown Manhattan and in the 1960s was adopted as the official emblem of the US government’s Project Plowshare.

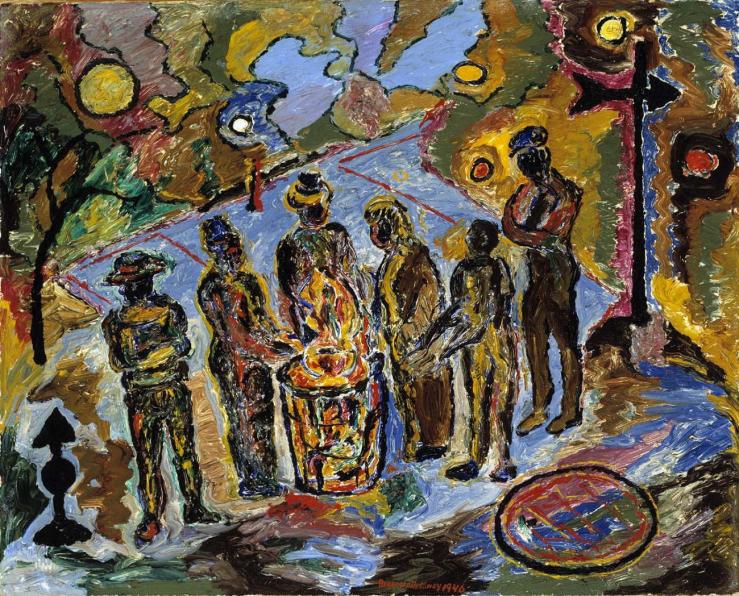

STATION 5. Simon of Cyrene Carries Jesus’s Cross

[1st Floor, South Wing – “Experience America”]

Commentary (Transcript): Can Fire in the Park by Beauford Delaney, 1946

The son of a Methodist Episcopal minister, Beauford Delaney demonstrated a penchant for art making at a young age—shaping figures from red clay in the parsonage yard and drawing Bible characters on his Sunday school papers. In 1923 he left his family home in Knoxville to study art in Boston. He then made his way to New York City in 1929, just at the moment when the Harlem Renaissance was waning and the Great Depression was beginning. He supported himself with various small jobs while painting portraits, interiors, and urban street scenes that focused on the poor and downtrodden.

Delaney’s style during his New York years can be classified as figurative expressionism. He was greatly influenced by postimpressionists like van Gogh, whose technique of thickly applied oil paint, called impasto, he adopted, and also by the Fauves, who were known for their use of pure bright colors and wild brushwork. This comes across in his 1946 painting Can Fire in the Park, which shows six homeless men gathering around a firelit oil drum for warmth and companionship. Delaney struggled financially all his life, so this empathetic scene may represent a night he once spent on a park bench alongside other marginalized folk in the community.

At the fifth station of the cross, Simon of Cyrene takes the cross off Christ and carries it for him to Golgotha, very tangibly supporting him in his sorrow. This act of compassion inspired, in 1963, the UK-wide Simon or Cyrenian movement, a collective of organizations dedicated to sharing the burdens of disadvantaged members of society. A hallmark of the movement is the alternative communities that have sprung up, in which homeless singles and local volunteers live together in shared housing, providing not just assistance but a sense of belonging.

This station begs the question: How might we help alleviate the burdens of the hurting? How might we provide warmth and companionship, that metaphoric can fire?

STATION 6. Veronica Wipes Jesus’s Face

[4th Floor, Luce Foundation Center, 53B]

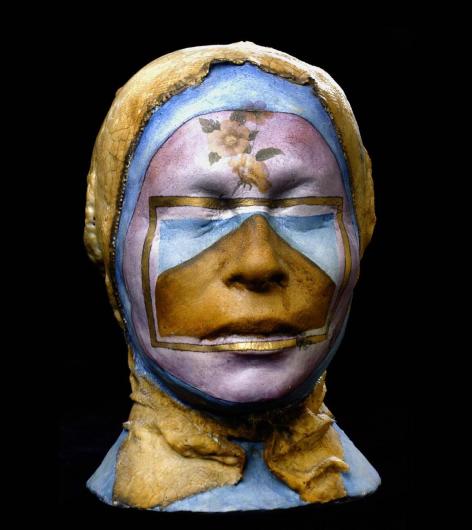

Commentary (Transcript): Dream Sequence by Bruria Finkel, 1976

Veronica is an apocryphal character in the story of Christ’s passion, who wasn’t introduced until the Middle Ages. According to legend, on the road to Calvary she wiped the blood and sweat from Christ’s face with her veil, and the veil forthwith received a miraculous imprint of his features.

This painted porcelain sculpture by Bruria Finkel, titled Dream Sequence, is to me evocative of that episode. The head is wrapped in actual cloth, inspired by the lace head coverings the artist’s Jewish mother would wear during Sabbath celebrations, and the gold-rimmed rectangle that bisects the figure’s lips and eyelids could also be a veil of some kind. This woman, whoever she is, appears to be basking in a meditative state of grace; perhaps she has just encountered the Divine. Flowers spring up across her forehead and alongside the back of her head, where they attract a swarm of butterflies.

Finkel’s art is inspired in large part by Jewish mysticism. In addition to studying and translating texts from that tradition and making art, Finkel is also a curator, educator, and advocate for greater female representation in museum art collections.

STATION 7. Jesus Falls a Second Time

[2nd Floor, East Wing – “American Art through 1940”]

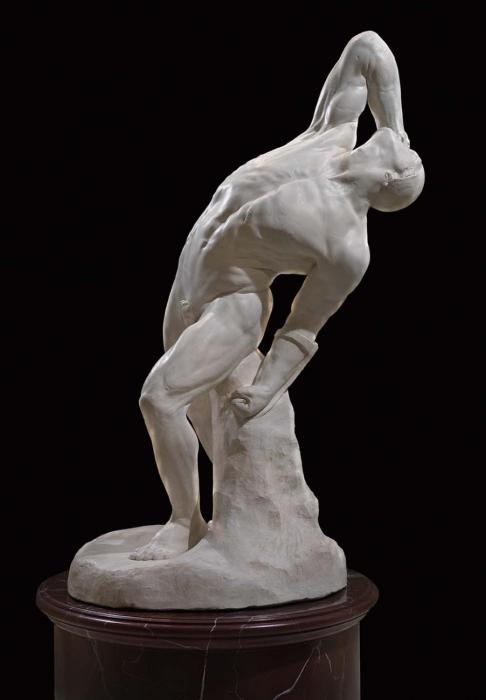

Commentary (Transcript): The Falling Gladiator by William Rimmer, 1861

At station 7 our hero falls again—as does this contemporary of Jesus, The Falling Gladiator, sculpted by Boston-based artist William Rimmer. Rimmer practiced medicine for years before turning to sculpting and painting in the late 1850s, eventually leaving the medical field to start an art school. His remarkable command of anatomy enabled him to create very lifelike figures, like this mortally wounded gladiator toppling backward while trying to draw his opponent’s sword out of his back. The sculpture was completed in January 1861—a tenuous time in America, as six states had seceded from the Union; just three months later, the Civil War began. When young American men at their physical prime started falling to each other’s gunfire, Rimmer’s sculpture gained a new resonance.

STATION 8. Jesus Meets the Women of Jerusalem

[1st Floor, West Wing – “Folk and Self-Taught Art”]

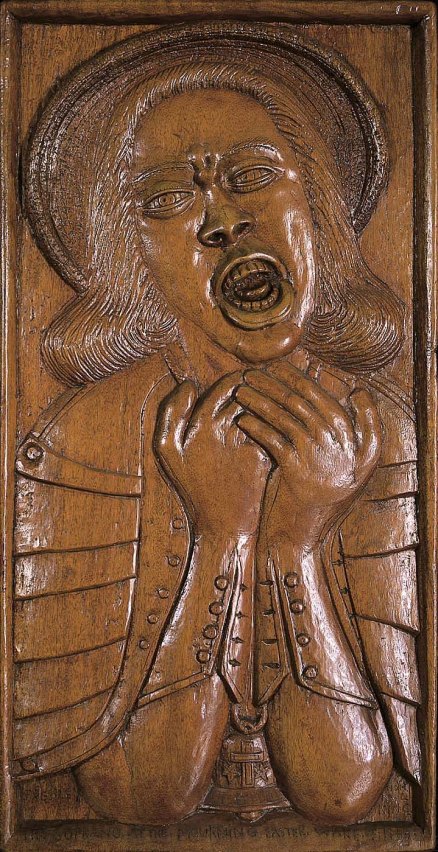

Commentary (Transcript): The Soprano at the Mourning Easter Wake of 1968 by Daniel Pressley, 1968

“And there followed him a great multitude of the people and of women who were mourning and lamenting for him. But turning to them Jesus said, ‘Daughters of Jerusalem, do not weep for me, but weep for yourselves and for your children’” (Luke 23:27–28).

As Jesus processed to his death on Good Friday, the Jewish women wailed for the loss of their great leader. Daniel Pressley’s relief carving seen here captures that anguish, that grief, unleashed by the death of a loved one. Titled The Soprano at the Mourning Easter Wake of 1968, it depicts one of the singers at Martin Luther King Jr.’s memorial service in Memphis the day after he was assassinated. She wrings her gloved hands and lets out an agonized moan, her eyes heavy with tears. The brim of her hat looks like a halo, and a cross dangles from around her neck.

African Americans have a heavy cross to bear—namely, a shared history of enslavement, brutality, and discrimination against their persons, which in many ways is not past. King’s gospel message of love, equality, and racial reconciliation was an additional cross he bore, along with many other civil rights activists, and he bore it to the death.

Pressley became aware of racism at a young age when his father was shot by a white neighbor on their South Carolina farm. Shortly after, he moved with his brothers and sisters up to Ohio, and then struck out on his own in Harlem, where he started to carve and paint images that dealt with his experiences as a black man. He was fifty years old when King was assassinated, and he immediately responded with this emotionally intense image. Pressley died three years later.

STATION 9. Jesus Falls a Third Time

[2nd Floor, North Wing – “American Art through 1940”]

Commentary (Transcript): Wheat by Thomas Hart Benton, 1967

Born in Missouri in 1889, Thomas Hart Benton was at the forefront of the regionalist art movement, which sought to depict realistic scenes of rural and small-town America, primarily in the Midwest and Deep South. Benton declared himself an “enemy of modernism,” rejecting the European-influenced abstraction that was becoming popular in the US. Everyday people and landscapes, he believed, were the proper subject matter for American art.

When Benton painted Wheat in 1967, regionalism had long since fallen out of favor. Still, Benton continued to paint scenes such as this one, harking back to a day when America was heavily agricultural.

Jesus regularly used examples from the world of farming to teach spiritual lessons, as it was a subject his audiences knew a lot about. During his final week, for example, he spoke this parable on death and resurrection: “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit” (John 12:24). He was talking about himself.

In Benton’s painting, a row of flowering wheat rises up proudly from the soil. But one of the stems has snapped, its head falling to the ground. This is part of the life cycle of wheat. It grows, it withers, its kernels fall into the earth, and that burial then becomes a source of new life.

STATION 10. Jesus Is Stripped

[4th Floor, Luce Foundation Center, 40A]

Commentary (Transcript): The Naked Man by Joseph Hirsch, 1959–62

At station 10 Jesus is stripped of his clothing, which the Roman soldiers then divide up amongst themselves, casting lots to determine what each should take. The Romans crucified criminals naked and in public so as to further humiliate them.

The Naked Man by Joseph Hirsch represents a different narrative context, but the vulnerability that comes with being unclothed, and a somber sense of calling, can be read in the painting. This tall young man has just been drafted into military service, as signified by the dog tags and boots around his neck. His pale bare skin against the dark background emphasizes the starkness of this ritual act: stripping off the old civilian life and putting on the life of a soldier. The youth has just performed the first part and now he braces himself for the second, preparing to walk the red-arrowed path marked out before him.

STATION 11. Jesus Is Nailed to the Cross

[4th Floor, Luce Foundation Center, 49B]

Commentary (Transcript): The Unknown Political Prisoner by Roberto Estopiñán, 2008

For his entire life Roberto Estopiñán felt the ethical need to be engaged in the struggle for a better Cuba. In 1949 he was a founding member of the cultural group Nuestra Tiempo, and after Fulgencia Batista seized power of the country in 1952, he fought against him as an urban guerrilla. When Fidel Castro took over in 1959, Estopiñán joined the diplomatic service, but by 1961 he had become disillusioned with the dictatorial policies of the new regime and went into exile in the US. He lived in New York City until 2002, when he retired to Miami, Florida. He died in 2015.

Estopiñán was a reader of Camus. One of the passages he underlined in his copy of the French philosopher’s journal reads, “The artist must never be an ally of the powerful. The role of the artist is not simply to live history, he is to be on the side of those who suffer history. He is to be their voice when they are voiceless.” Estopiñán heeded this call and in the 1960s began an ongoing series of drawings and sculptures of political prisoners and crucifixions, giving voice to what was a terrible reality in his native country. In this bronze, titled The Unknown Political Prisoner, a faceless man, enfeebled from beatings, bows his head. His hands are restrained behind his back, and a thick barbed wire, symbol of his imprisonment, spans the height of his body. He is pinned to a wall, much like Jesus was nailed to the cross.

Political prisoners all throughout Latin America often report how they find strength in the example of Jesus Christ, a revolutionary who was for the people over and against oppressive systems. In 1974 an anonymous political prisoner in Chile wrote the poem “He Said He Was a King,” excerpted as follows:

The armed retinue was mocking

the one crowned with thorns.

They took off his rags

and beat his head with a cane.

Offensive mouths spat on the man

with the long hair, rebel eyes, and unkempt beard.So, mocked by the soldiers

and with a mistreated body,

a bloodied man was dying

before the eyes of the high priests—

supreme hypocrisy, supreme meanness and greed.Today I remember you, a freedom-loving Christ,

vagabond in time, dubious in space.

Were you Spartacus’ brother,

contemporary of the slave, or comrade worker?What matters the chain, the fiefdom, the wage,

to be Nazarene or Chacabuco inmate,

if you are on earth, brother Christ,

Son, with dirty face and calloused hands,

flesh and blood of the people, lord of history,

at home with the plane and hammer,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Eternal resident of the poor and barren hovel

with roof of tin or stars, floor of sand or dirt,

modest or captive walls,

you do not dwell in the oppressive mansion,

the caves of thieves, or the palace of Caesar.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Yes, I prefer the witness

of the one who walks, suffers, and loves,

of one who sings, weeps, and loves,

of one who struggles, dies, and loves.I understand you, Christ,

because I know betrayal and the spear,

because, like you, I say

I am king and claim my crown.

(Station 11, cont.) [1st Floor, South Wing – “Experience America”]

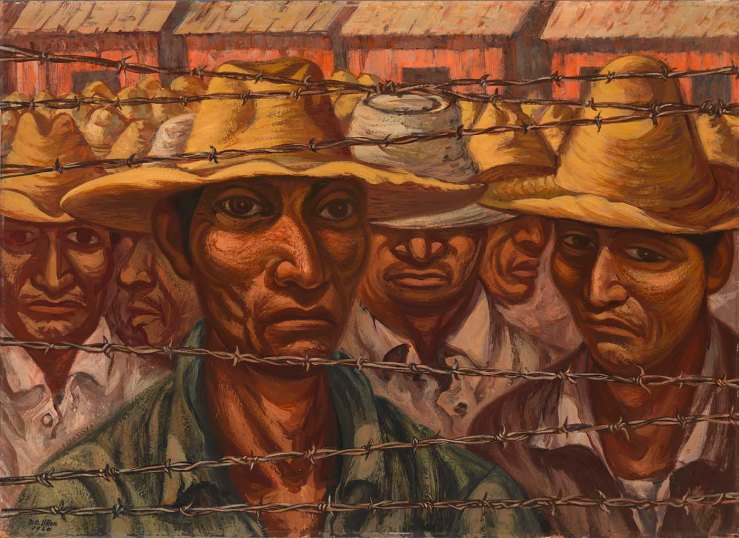

Commentary (Transcript): Braceros by Domingo Ulloa, 1960

Barbed wire is also featured prominently in this second image for station 11, a painting by Chicano artist Domingo Ulloa titled Braceros. The Bracero Program, launched in 1942, brought Mexican guest workers to the US to fill in agricultural labor shortages caused by World War II. While it sounded great on paper, the braceros faced harsh living and working conditions and discrimination and were often cheated of their wages. A US Department of Labor officer at the time referred to the Bracero Program as “legalized slavery.”

Ulloa painted this scene after several visits to a bracero camp in Holtville, California, where he observed these injustices firsthand. Its composition—a crowd of workers peering dejectedly through a barbed-wire fence—recalls the photographs of Nazi concentration camp inmates, which, as a World War II veteran, Ulloa was all too familiar with.

After twenty-two years of operation, the Bracero Program was terminated in 1964, but many of today’s migrant workers still face a lot of the same unjust treatment. Their plight received primetime attention in 2017 when season 3 of the Emmy-nominated television drama American Crime aired, with one of its two main story lines set on a farm in North Carolina.

STATION 12. Jesus Dies on the Cross

[3rd Floor Mezzanine, Luce Foundation Center, 21B]

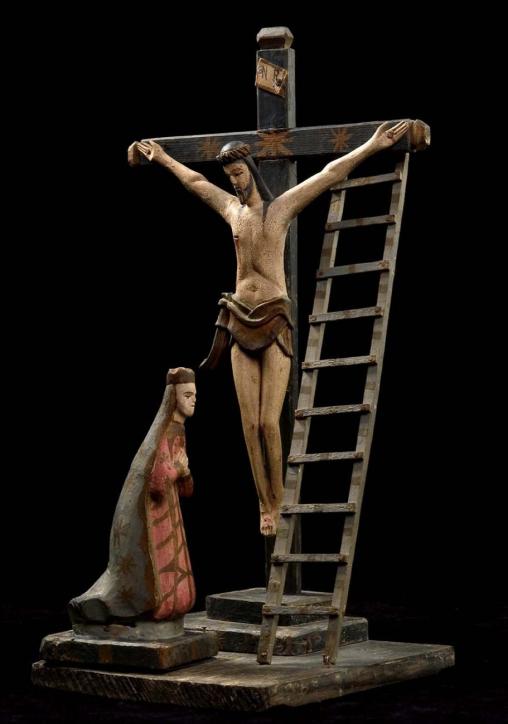

Commentary (Transcript): Calvario by the Cabán group, ca. 1875–1900

Like the Christ of humility at station 2, this Spanish colonial–era sculpture, Calvario, is from Puerto Rico, and it’s part of the santos tradition. Popular throughout the Latin world, a santo is an artistic representation of a saint or religious figure that’s used in Catholic devotions; in Puerto Rico, they’re mostly all wood-carved. This one, made during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, is attributed to the Cabán group, a family of carvers active from the eighteenth century to the second half of the twentieth.

The sculpture shows Jesus on the cross having breathed his last breath, his mother collapsed to her knees in grief. A ladder has already been propped up against the cross to retrieve the dead body. “It is finished,” as Christ said; his atoning death has been accomplished.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum has one of the largest collections of Puerto Rican santos in the world—over six hundred. They were all donated by the self-taught historian, folklorist, and material culture preservationist Teodoro Vidal and constitute one of the most significant donations in the museum’s history.

(Station 12, cont.) [3rd Floor, East Wing – “Contemporary Art”]

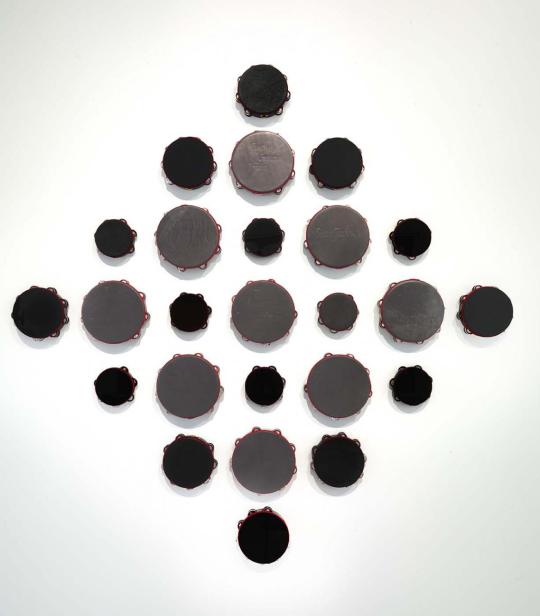

Commentary (Transcript): Requiem for Charleston by Lava Thomas, 2016

On June 17, 2015, white supremacist Dylann Roof entered the midweek prayer service at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and shot dead nine of its members with the express purpose of igniting a race war. Requiem for Charleston by Lava Thomas honors the memory of these men and women.

This mixed-media artwork features an arrangement of tambourines whose axes form the shape of a cross. Nine of the tambourine heads are made of black lambskin—a symbolic material, connoting innocence and sacrifice—and are inscribed with the victims’ names using pyrographic calligraphy. Thomas said she wanted the names to be subtle so that viewers will move up close to the piece and spend time deciphering.

Some of the tambourines are left blank in memory of the many other men, women, and children who have died in acts of racial violence against churches throughout history. Others are made of black acrylic discs that reflect the viewers’ faces, reminding us that the Charleston mass shooting is a human tragedy we all share, one that demands collective mourning and a collective assumption of responsibility.

Tambourines have a lot of personal significance for Thomas, as she grew up playing the instrument in her grandmother’s church. Tambourines are used in many cultures as a form of expression in worship and in protest. In the black church they often provide the principal rhythmic driving force of the service. Here, though, instead of jingling, the bells are still, a silent tribute to the lives lost.

STATION 13. Jesus Is Taken Down from the Cross

[4th Floor, Luce Foundation Center, 32A]

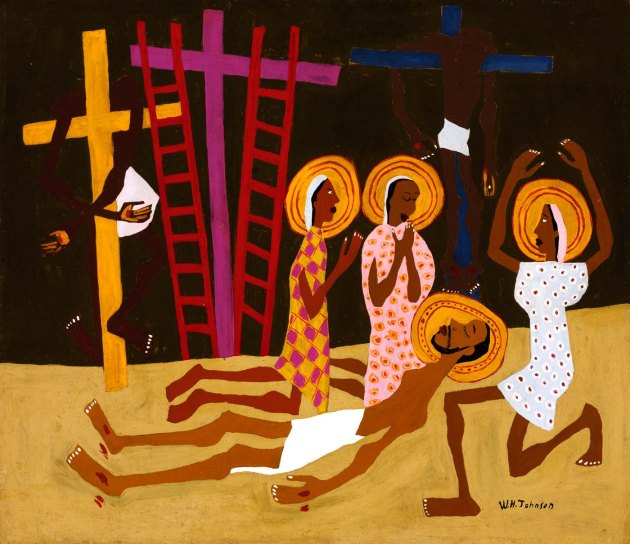

Commentary (Transcript): Lamentation by William H. Johnson, 1944

We met William H. Johnson at station 3, The Breakdown. In 1944 Johnson’s wife, Holcha, died of cancer. He was devastated. He painted Lamentation that year while processing his grief, along with other scenes of the dead Christ, like Mount Calvary, also owned by this museum. Shortly after, Johnson developed a mental illness—diagnosed as paralytic dementia—and he spent the last thirty-three years of his life at a hospital in New York, unable to produce any art.

In Johnson’s Lamentation, Jesus has just been taken down from the cross; he lies on the cold ground, the blood from his wounds seeping into the earth. Surrounding him in mourning are the three Marys John mentions in his Gospel as having been present at the Crucifixion: Jesus’s mother; his mother’s sister, who is the wife of Clopas; and Mary Magdalene (John 19:25). They wear patterned cotton dresses, gold halos, and varied reactions to the death of their beloved. Behind them the sky is dark, as if it too is in mourning. The corpses of the two criminals Jesus was killed with still hang on their crosses.

STATION 14. Jesus Is Buried

[3rd Floor, North Wing – “Art Since 1945”]

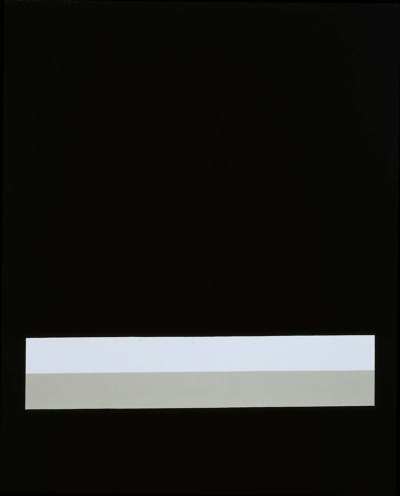

Commentary (Transcript): #13-1973 by John McLaughlin, 1973

John McLaughlin studied Japanese art and language for years in both the US and Japan before he began painting at age forty-eight. Greatly influenced by the Zen Buddhist notion of emptiness, or the “marvelous void,” he wanted to create neutral abstract forms that would promote deep introspection. He did that by developing what’s known as the California hard-edge style of painting, characterized by geometric compositions, straight edges, and rich, solid colors.

In this untitled work of his from 1973, McLaughlin layers two rectangular bars—one white, one gray—on top of a solid black plane, situating them in the bottom third of the canvas. Though a narrative reading is counterproductive to the Zen meditation the artist hoped to inspire, I can’t help but see the dead and buried Christ, enveloped in the darkness of his tomb, and recall the first three lines of Elizabeth Rooney’s poem “Easter Saturday”:

A curiously empty day,

As if the world’s life

Had gone underground.

CODA: “Rosing from the Dead”

[3rd Floor, East Wing – “Contemporary Art”]

In place of commentary for Gold Morning with Roses by Pat Steir, 1999, a poem:

“Rosing from the Dead” by Paul J. Willis

We are on our way home

from Good Friday service.

It is dark. It is silent.

“Sunday,” says Hanna,

“Jesus will be rosing

from the dead.”

It must have been like that.

A white blossom, or maybe

a red one, pulsing

from the floor of the tomb, reaching

round the Easter stone

and levering it aside

with pliant thorns.

The soldiers overcome

with the fragrance,

and Mary at sunrise

mistaking the dawn-dewed

Rose of Sharon

for the untameable Gardener.

“Rosing from the Dead” by Paul J. Willis appears in the poetry collection Rosing from the Dead (WordFarm, 2009) and is used by permission of the publisher.

This concludes the Stations of the Cross tour at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, organized, written, narrated, and produced by Victoria Emily Jones. For weekly art, music, and poetry presented from a Christian faith perspective, visit ArtandTheology.org, and follow Victoria on Twitter @artandtheology.

+++

FEEDBACK: If you participated in this tour, I would love to hear your feedback, either in the comment box below or via e-mail (victoria.emily.jones@gmail.com). What was the experience like for you? What work made the biggest impression? In the commentary, did you feel there was an appropriate balance of artist biography, image analysis, and devotional reflection, or would you have liked it to be heavier/lighter in one area? Did you appreciate the music overlays, or were they distracting? Was the SoundCloud audio distribution platform convenient and practicable? Short of hiring professionals to read and studio-record the commentary, design the album cover and promotional materials, and develop a custom app, is there anything you would have changed about the tour? (Note: I did reach out to the museum and unfortunately, because I’m not an established partner, they are not able to help me promote the tour.)

Again, I really appreciate your input, as it will guide me in developing similar products in the future. Thank you!

MUSIC CREDITS

Intro, Stations 1, 2a–b, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11a–b, 12a, 13, 14: Largo for Violin, Clarinet, and Piano by Charles Ives, performed live by violinist Lucy Stoltzman, clarinetist Richard Stoltzman, and pianist Jeremy Denk. Licensed by the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, under the Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Station 2b: “Look Way Down That Lonesome Road,” traditional, performed by Mississippi Fred McDowell, 1965

Station 8: “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” by Thomas A. Dorsey, performed by Mahalia Jackson, 1956. This was Martin Luther King Jr.’s favorite song, and he often invited Jackson to sing it at civil rights rallies; at his request she sang it at his funeral. (She is not the one depicted in Pressley’s carving, however.)

Station 9: Aria Fantasy for Piano Quartet by David Ludwig, performed live by musicians from Ravinia’s Steans Music Institute. Licensed by the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, under the Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Station 12b: Excerpts from “Freedom Suite (a.k.a. Civil Rights Medley),” including the traditional black gospel songs “Oh Freedom” and “Come and Go with Me to That Land,” performed by Sweet Honey in the Rock on A Tribute—Live! Jazz at Lincoln Center, 2011

Coda: Piano Concerto No. 2 in F Minor, Op. 21: II. Larghetto by Frédéric Chopin, performed by pianist Martha Argerich & the National Symphony Orchestra Washington, 1989

I loved this, thank you. I particularly liked the ones with poetry, as I think you make links which open me to new ideas, thank you. After the first 2 I stopped listening as I found the verbal commentary and the music distracting. I really appreciated the transcripts- I found I could re-read them in different ways picking out different aspects each time: the Art methods, the painter, the social conditions. So many were about the Depression, or Jesus as a black person (Interesting we can represent Christ as a black man but not a woman…)

LikeLike

Thanks so much for the feedback. I’m glad you appreciated the poetry; I especially enjoyed working on those stations. I hope to feature more poetry on the blog this year.

I didn’t intentionally exclude women as Christ figures from the tour, but I guess it did pan out that way. I was considering using the Rosa Parks sculpture by Marshall D. Rumbaugh from the National Portrait Gallery (whose building adjoins the SAAM) for station 1, and Dorothea Lange’s famous Migrant Mother photograph, also in the NPG, for “Jesus Falls,” but ultimately decided to just stick with the SAAM collection. While there are artists who have represented women as Christ figures (e.g., on the cross), I’m not aware of any such explicit representations at the SAAM. The paintings of African Americans in the museum spoke powerfully to me of Christ’s journey to the cross, which is partly why you see them heavily present in the selections. Thank you for that observation!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is wonderful. I’m only part way through but can’t wait to finish this post.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for putting so much work and attention to detail into this. During Holy Week we host a congregational and community curated “Stations of the Cross” art installation at the church where I work. I have shared this site with the artists who are participating. I appreciate all you do to keep art at the forefront of faith.

LikeLike

Thank you for your kind words, Kiersten. That’s great that your church uses art to help shepherd people’s hearts during Holy Week. I pray that the installation is a blessing to all involved–both artists and viewers.

LikeLike

This is amazing! I’m looking forward to digging into this beautiful resource. Well done!

LikeLike

You have put an enormous amount of effort into this full and wonderful post. Thank you from across the sea!

LikeLike

As I live in the D.C. area (in Arlington), on the Thursday immediately following Ash Wednesday I took a friend to SAAM, one of my favorite museums. Unfortunately, only seven of the artworks can be seen; for those we gave thanks to a helpful young woman in the Luce Center who looked up the locations for us . The artworks are not so easy to find once leaving the Luce, but we did locate those works on view and found your commentary informative and valuable. It’s fabulous to see some of these artworks in person.

I returned the location information to the front desk staff, who did not initially understand what we were looking for, so that any other visitors coming to the museum as a result of your post could be directed appropriately.

LikeLike

[Update, 2/28: I confirmed with staff that all eighteen works are on view. If you want to be sure before you visit, you can check the status of each on the SAAM website, which, I found out, is always current down to the day.]

Hi Maureen,

I’m so glad you took the time to take the tour in person at the SAAM, and with a friend. I’m sorry you encountered difficulty finding the artworks. Was it (1) because the locations are mislabeled on this blog post, (2) just due to the generality of location and large size of the museum, or (3) due to the fact that some works have been removed from view?

Would you be able to send me a list of the works that were not on view during your visit? I’m surprised it’s so many, as just three weeks ago I went in person and confirmed that all were there. I guess it goes to show that the SAAM rotates their collections quite often.

Thank you for letting the front desk know. I did speak with museum staff about this tour back in January and hoped they would be able to work with me in some small measure, or at least notify other staff of the tour, and I sent my contact this link when it went live. I’m glad someone was able to assist you; hopefully your inquiries will encourage staff to look into it. All this feedback is very helpful–thanks!

-Victoria

LikeLike

[…] the self-guided “Stations of the Cross” audio tour of the Smithsonian’s American art collection, here are some other opportunities to engage in […]

LikeLike

Truly wonderful Victoria! This is beautiful work.

LikeLike

[…] this expansive view of the gospel in mind, this Lent I developed a Stations of the Cross “pilgrimage” using works from the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC. The eighteen pieces I chose […]

LikeLike

Beautiful and moving. I am appreciating your whole website very much.

LikeLike

[…] The two bultos (small religious carvings) pictured above were gifted to the Smithsonian, along with 3,200-plus other objects, by Puerto Rican folk art collector Teodoro Vidal. Learn more about the Vidal Collection at https://amhistory.si.edu/vidal/. (You may remember me speaking about another bulto donated by Vidal, Señor de la Humildad y la Paciencia, in my Stations of the Cross audio guide.) […]

LikeLike

Dear Victoria, thank you so much for all the effort and love that you put together and made it visible for us readers from around the world. I appreciate your “Visio Divina” and combination of Art and Theology very much.

A big thanks from Salzburg, the city of Mozart in Austria

Yours, Claudia

LikeLike

[…] posts: “Stations of the Cross at the Smithsonian American Art Museum”; “Remembering […]

LikeLike

[…] Stations of the Cross at the SAAM (Art & Theology) […]

LikeLike

[…] Johnson (1901–1970) is one of my favorite artists—I wrote about him in stations 3 and 13 of the Stations of the Cross audio tour at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and in my review of Beholding Christ and Christianity in African American […]

LikeLike

[…] For another painting by Hirsch from the blog, see “Stations of the Cross at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.” […]

LikeLike

[…] years ago I developed a Stations of the Cross tour through the Smithsonian American Art Museum, engrafting the story of Christ’s passion into other stories of human […]

LikeLike

[…] years ago I developed a Stations of the Cross tour through the Smithsonian American Art Museum, engrafting the story of Christ’s passion into other stories of human […]

LikeLike

[…] American Art Musuem. Here is the video, the bulletin and you can read more about the art pieces (ttps://artandtheology.org/2018/02/11/saamstations/ ). If we had been together, we would of done this at 7PM tonight but feel free to do this at a […]

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this. Stations of the Cross is a big part of Lent, for me; I enjoy going every year. Because we are social distancing, I looked online to find a Stations to listen to. I am so happy to have come across this beautiful version that includes American art. I really appreciate being able to participate even though it’s not in person. All my best, Paige

LikeLike

Thank you very much for your work in putting this together. The same stations experienced in a different way provides new meaning and depth to this day. And to do in a year when the country is reeling makes it even more valuable.

LikeLike

[…] Reflect on artwork associated with the Stations of the Cross, such as this virtual audio tour from the Smithsonian American Art Museum. […]

LikeLike

[…] project that Rosen cofounded (which I chronicled in detail here), and his project inspired the Stations of the Cross experience I designed, independently, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum—which, I know from people having reached […]

LikeLike

[…] artists. Included are several artists I’ve featured on the blog before—Lava Thomas [here], Kehinde Wiley [here], Clementine Hunter [here], Letitia and Sedrick Huckaby [here]—plus […]

LikeLike

[…] Smithsonian American Art Museum have put together these Stations of the Cross. These images will move […]

LikeLike