This week Christianity Today published an article by theology and culture professor W. David O. Taylor, titled “Why Putting Christ Back in Christmas Is Not Enough.” I highly recommend it. In it Taylor discusses four fundamental influences on the way Christmas is celebrated in America, beginning with its illegalization by Puritans in the seventeenth century. One public notice warned citizens:

The observation of Christmas having been deemed a Sacrilege, the exchanging of Gifts and Greetings, dressing in Fine Clothing, Feasting and similar Satanical Practices are hereby FORBIDDEN, with the Offender liable to a Fine of Five Shillings.

“So what happens,” muses Taylor,

when the Protestant church in the 17th century evacuates its worship of the celebration of Christ’s birth? A liturgical vacuum is created that non-ecclesial entities willingly fill. The government determines the legal shape of Christmas, the market shapes a society’s emotional desires and financial expectations about the holy day, the ideal family replaces the holy family, and the work of visual artists shape its imagination, while musicians and writers fill the empty space with their own stories about the “magic” of Christmas.

Taylor is not saying we can’t enjoy any of the secular trappings of Christmas (“the grace and goodness of God are not absent from these things”), only that we should recognize that the Christmas story told in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke is far more fantastical, more difficult and dangerous, more multicultural and multigenerational, and more relevant than the Christmas story America tells—including American civil religion.

This article was adapted from a lecture Taylor gave, as part of the Fuller Texas Lecture Series, to a gathering of scholars and artists at Christ the King Presbyterian Church in Houston on October 20, which can be streamed via Facebook. (Starts at about 22:40.) The focus is on the critical role songwriters can play in reorienting our imaginations back toward the scriptural accounts of Christ’s birth, going beyond the sentimental and nostalgic into a more thorough habitation of the story in all its shades.

What if the narrative of Matthew and Luke were more determinative of our Christmas holidays than the narrative of Wall Street and primetime television? What if our Christmas songs gave our congregations a chance to sing to God from the depths of their hearts—of their heart’s longings and wonderings, hopes and fears, certainties and doubtings, joys and melancholy yearnings? What if our Christmas songs gave our congregations a chance to encounter the good news afresh—in a way that exceeded their sense of how deeply good, richly mysterious, and wonderfully paradoxical that news could in fact be? What if our Christmas songs offered an opportunity for our congregations to be attuned to each other—across the aisle as well as across denominational and cultural and geographic and linguistic lines—in a way that we never imagined possible?

This lecture was the capstone of the second workshop of the Christmas Songwriters Project, a new initiative sponsored by the Brehm Center for Worship, Theology, and the Arts, the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship (CICW), and Duke Divinity School. Co-directing the project along with Taylor are Noel Snyder, a program manager at the CICW with a background in musicology, and Lester Ruth, a historian of Christian worship at Duke. The first workshop, held in March in Grand Rapids, Michigan, brought together twenty-four Christian songwriters from across the US who were specially invited to participate. Following its success, a second one took place October 18–19 in Houston with a new set of eighteen select songwriters, all local. The hope is to conduct future workshops, as soon as next fall, in Nashville, and later in New York City and Los Angeles. A website for the Christmas Songwriters Project is under development and is likely to launch this coming spring.

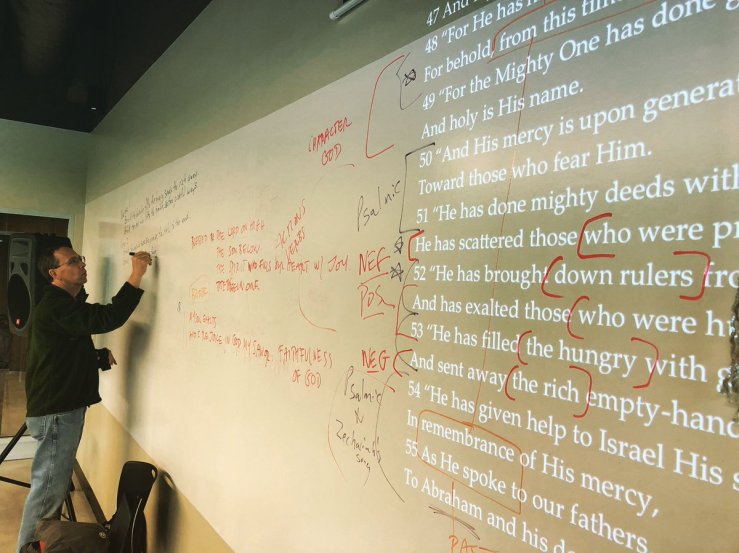

Over the course of two days, the Houston songwriters performed a close reading of the infancy narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke; studied Charles Wesley’s Hymns for the Nativity of Our Lord, a collection of eighteen of his hymns, published in 1745; and sought to get a sense of the musical aesthetics of today’s top fifteen Christmas carols. They asked themselves a double question: What does Christmas sound like? And what should Christmas sound like? (What new sounds are needed to re-sound the stories in Matthew and Luke?)

During these workshops, there was a heavy emphasis on collaboration. Several fine songs have resulted, which are in various phases of production. Six premiered in their earliest forms in the above video, interspersed with Taylor’s lecture.

One of the highlights is a reprise of the saccharine “Away in a Manger” that takes into account the Massacre of the Innocents and the resultant flight to Egypt of the Holy Family, thereby giving a broader view of the Christmas story, one that coheres better with the Matthean narrative, which ends with Rachel weeping. The clever twists on the original lyrics and the grayer tonality give a sense of the darkness into which Jesus came and also resonate with the experiences, hopes, and fears of many contemporary refugees.

“Away from the Manger: The Refugee King” – Words and music by Liz Vice, Wen Reagan, Bruce Benedict, Greg Scheer, and Lester Ruth | Performed by Liz Vice (lead vocals) and Hannah Glavor (guitar and backing vocals)

[Update, November 8, 2019: Liz Vice has just released “Refugee King” as a single!]

Away from the manger they ran for their lives

The tiny boy Jesus a son they must hide

A dream came to Joseph, they fled in the night

And they ran and they ran and they ranNo stars in the sky but the Spirit of God

Led down into Egypt from Herod to hide

No place for his parents, no country or tribe

And they ran and they ran and they ranStay near me, Lord Jesus, when danger is nigh

And keep us from Herods and all of their lies

I love thee, Lord Jesus, the Refugee King

And we sing and we sing and we sing

And we sing and we sing and we singAlleluia (×5)

(Related post: “Songs about the Flight to Egypt”)

Another highlight is the song “Savior of Mankind,” an original setting of a hymn text by Charles Wesley, performed at around 51:00 in the lecture video. It captures a sense of the cosmic import of the Nativity, and of the overlap of heaven and earth that is the Christ. The line “’Tis all your heav’n on him to gaze”—wow.

“Savior of Mankind” – Words by Charles Wesley, 1745 | Music by Luke Brawner, Joe Deegan, Rebekah Maddux El-Hakam, and Paul Yoon, 2018

Let angels and archangels sing

The Son of God, Immanuel’s Name

Adore with us our newborn king

And still the joyful news proclaimAll heav’n and earth be ever joined

To praise the Savior of mankind (×2)The everlasting God comes down

To walk with the sons of men

Without his majesty or crown

The great Invisible is seenOf all his dazzling glories shorn

The everlasting God is born (×2)Angels, see the infant’s face

With rapt’rous awe the Godhead own

’Tis all your heav’n on him to gaze

And cast your crowns before his throneNow he on his footstool lies

For he built both earth and skies (×2)By him into existence brought

You sang the all-creating Word

You heard him call our world from naught

Again, in honor of your LordYou morning stars, your hymns employ

And shout, you sons of God, for joy (×2)

Seriously? in 2019 a Christmas carol with the line–“God came down to walk with the sons of men”? Remember what Sojourner Truth said, “Who brought Jesus into the world? It was God and a woman–man had nothing to do with it.”

LikeLike

“Sons of men” (ben ‘adam) is a biblical expression that refers to humankind at large. (And “sons of God” in the last line is taken from Job 38:7, where it refers to [sexless] angels–as does “morning stars.”) The text is Wesley’s. But I know in this day and age, the gendered language can trip up some people. How would you recommend those two lines be rewritten to be more gender-inclusive and still retain their poeticality and allusion?

LikeLike

what to do about christmas carols which exclude more than half the population by their use of pronouns?

LikeLike

Most languages in the world follow the principle that mixed company is referred to by masculine pronouns. In English we are lucky enough to have some expanded pronouns (though maybe not as lucky as some languages that have no gendering altogether). Our culture is getting sensitive to gender in a way that demands more inclusive precision, but maybe we should just accept that some things in our culture need to be understood as products of their own history.

And some rewrites work well. I’ve seen “men” replaced by “friends” in a few songs (“Good Christian Friends Rejoice” “God Bless Ye Merry Gentle Friends”) and while the word isn’t as mouth-friendly it adds some nice connotations that align with many Christmas themes of good will.

LikeLike

[…] whom I’ve featured before on Art & Theology, like Jonathan A. Anderson, Matthew J. Milliner, W. David O. Taylor, and Terry Glaspey—they have all been influential to me. I’m very encouraged to see this major […]

LikeLike

[…] expand the church’s repertoire of Christmas music, Taylor founded, along with a few others, the Christmas Songwriters Project. The Psalms are an inspiration in this task, as they express a joy that is at times quiet and at […]

LikeLike

[…] (Related post: “The Christmas Songwriters Project”) […]

LikeLike