Would God I knew there were a God to thank

When thanks rise in me, certain that my cries

Do not like blind men’s arrows pierce the skies

Only to fall short of my quarry’s flank.

Why do I thirst, a desperate castaway

Quaffing salt water, powerless to stop,

Sick lark locked in a cellar far from day,

Lone climber of a peak that has no top?

To praise God is to bellow down a well

From which rebounds one’s own dull booming voice,

Yet the least leaf points to some One to thank.

The whorl embodied in the slightest shell,

The firefly’s glimmer signify Rejoice!

Though overhead, clouds cruise a sullen blank.

This poem was originally published in In a Prominent Bar in Secaucus: New and Selected Poems, 1955–2007 by X. J. Kennedy (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007). Used by permission of the publisher.

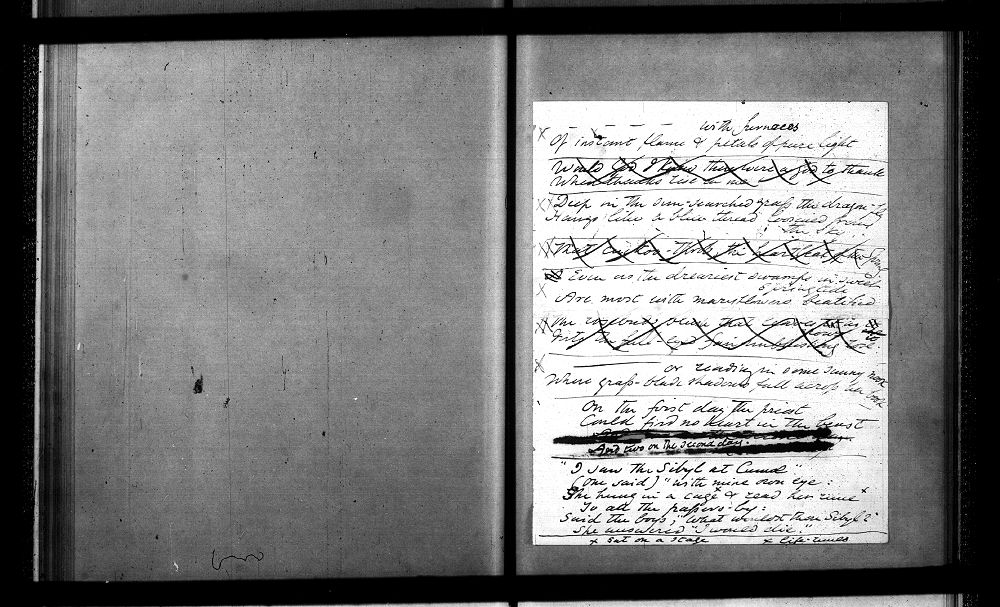

The first line and a half of this sonnet are a crossed-out fragment from one of the notebooks of the British poet and artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), which he used to work out poetic ideas. This one never went anywhere. But Rossetti’s brother, William Michael Rossetti, saw something in it worthy of preservation; he salvaged it and other select scraps from his brother’s papers, publishing them posthumously in a “Versicles and Fragments” section of Rossetti’s collected works in 1901.

The modern American poet X. J. Kennedy developed Rossetti’s fragment into a full poem that grapples with the silence of God and, despite such, the impulse to praise. The speaker is confounded by the contradiction that the world seems infused with God’s presence—the natural world points to a Creator—and yet God is unresponsive when the speaker initiates contact. The prayers he launches toward heaven like arrows appear not to reach their target. He’s experiencing spiritual aridity. He feels like a thirsty castaway whose only drink is salt water (why doesn’t God satiate as promised?); a bird trapped in a dark cellar; a mountain climber endlessly climbing, never catching sight of the vista.

The poem tugs back and forth between despondency and awe, between clench-fisted frustration and open-handed surrender. Each glorious tree leaf, the intricate design of conch shells, the whimsy of lightning bugs—these are gifts, but where’s the giver? Gratitude must be directed to someone, but whom does one thank for the wonders and small joys experienced in nature? Who or what is their source? Oh, how I wish I knew there were a God out there to thank, when thanks well up in me. The speaker wants to place his thanks somewhere, but when he places them in God, he receives no confirmation of receipt. There’s a disconnect between what nature testifies and what the speaker has suffered: the “sullen blank” of heaven.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s brother, William, wrote in 1895 that, unlike their devout sister Christina [previously], Dante was “a decided sceptic. He was never confirmed, professed no religious faith, and practised no regular religious observances; but he had sufficient sympathy with the abstract ideas and the venerable forms of Christianity to go occasionally to an Anglican church—very occasionally, and only as the inclination ruled him.” Starting in mid-adolescence, he rejected organized religion.

Kennedy, similarly, was raised in a religious household: his father was Catholic, his mother Methodist. And yet in his adulthood he has come to question and reject some of the tenets of orthodox Christianity. But still, he searches for God. “There is a clash in his poems between his skepticism or uneasy agnosticism and his unresolved longing for faith in God,” reads his bio on the Harvard Square Library website. Kennedy’s desire to believe but his inability to do so is expressed recurringly in his work—as in this poem, in which he, taking the baton from Rossetti, is very likely the speaker.

X. J. Kennedy (born 1929) is an American poet, translator, editor, and author of children’s literature and textbooks on English literature and poetry. Born Joseph Charles Kennedy in Dover, New Jersey, he adopted the nom de plume X. J. Kennedy in 1957 to avoid being mistaken for the better-known Joseph Kennedy, then US ambassador to England and father of future president John F. Kennedy. His award-winning poetry collections include Nude Descending a Staircase (1961) and Cross Ties (1985). He lives in Lexington, Massachusetts.