Christianity has had a long and deep presence in Egypt. The art historical record is one means of exploring that.

From mid-thirteenth-century Egypt there survives an illuminated New Testament written in Bohairic Coptic with glosses in Arabic. It was copied in Cairo in 1249–50 by Gabriel III (born al-Rashīd Farajallāh), who would serve as patriarch of Alexandria from 1268 to 1271, for the private use of a prosperous lay patron of the Coptic Church. The images are most likely the work of a single artist and his assistant.

This Coptic-Arabic New Testament is divided between two locations: the Four Holy Gospels in Paris (Institut Catholique, Ms. Copte-Arabe 1), and Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles in Cairo (Coptic Museum, Bibl. 94). In this post I will showcase the art from the Gospels portion.

Drawing on Byzantine and Islamic artistic influences, Copte-Arabe 1 “represents the culmination of painting in Egypt and the allied territory of Syria for the Ayyubid period [1171–1260] as a whole,” writes art historian Lucy-Anne Hunt. [1] The manuscript contains fourteen full-page miniatures and four Gospel headpieces. A later hand clumsily retouched in black ink some facial details that had become abraded over the years—so no, those marks most noticeable on folios 56v and 178v are not intended as mockery.

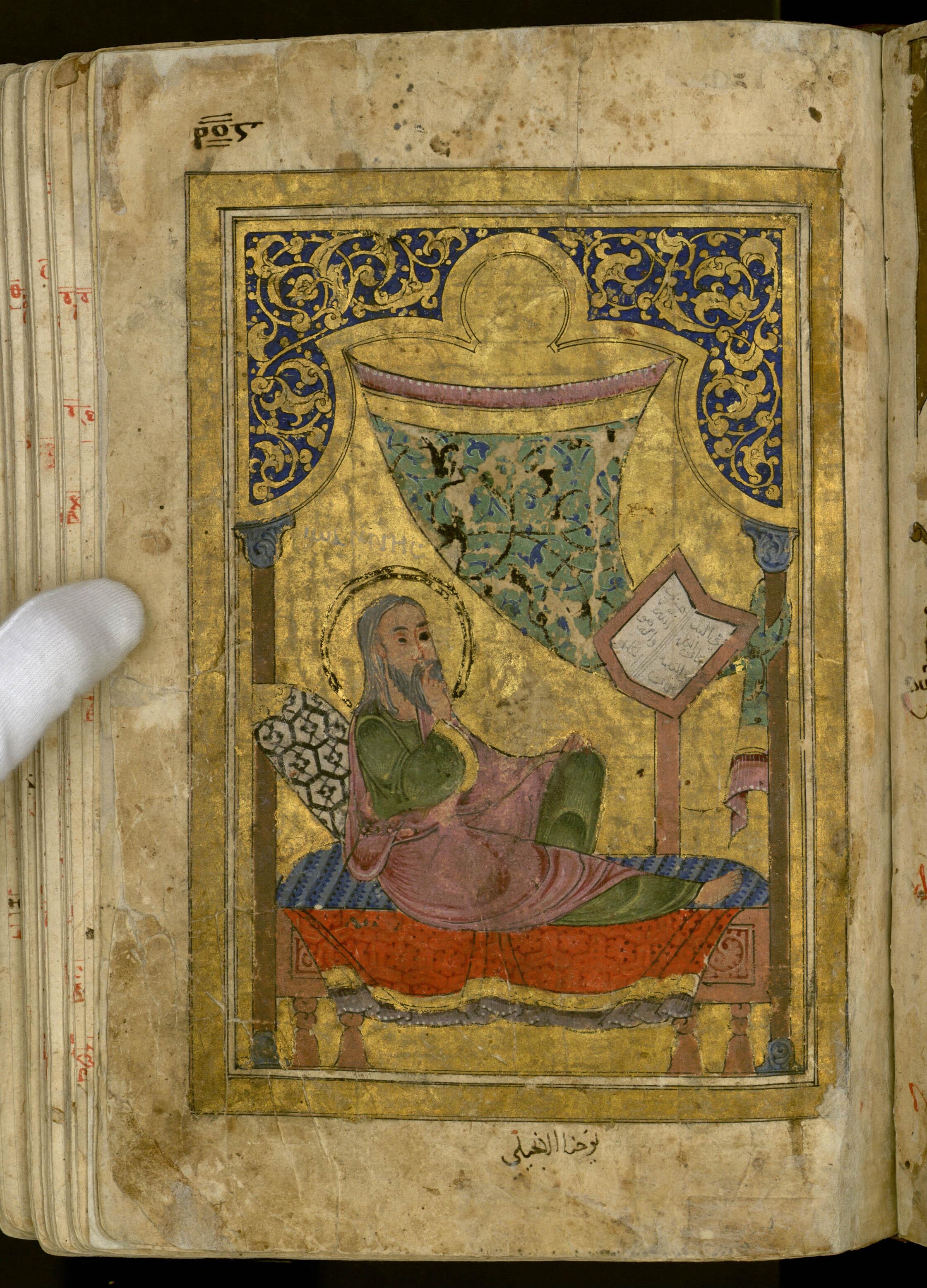

Of the fourteen full-page miniatures, four are portraits of the Evangelists (i.e., Gospel-writers): Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. These are the most refined and celebrated paintings in the manuscript.

Each Evangelist is shown under a cusped arch—Matthew copying his Gospel in Arabic, Luke seated in front of a pulled-back curtain with a lotus design pattern, and John uniquely reclining, a pose adapted from secular models.

But the most interesting of the four Evangelist portraits is Mark’s, because there’s another figure with him. The owning institution labels the page “Marc l’évangéliste; Pierre lui donnant l’Evangile” (Mark the Evangelist; Peter giving him the Gospel). I had to look into this!

Traditionally, a man named John Mark is credited as the author of the Gospel that begins, “The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ.” (It came to be called the Gospel of Mark by the end of the second century.) John Mark was a disciple of Peter, whom he is believed to have used as his primary source in composing his Gospel. The two were close companions, and Peter even refers to him as a son (1 Pet. 5:13). John Mark’s mother, Mary, hosted a house church that Peter was connected with (Acts 12:12). John Mark was also a cousin of Barnabas of Cyprus (Col. 4:10) and accompanied Paul in some of his apostolic travels (Acts 12:25; 13:1–5; 15:36–39).

Papias of Hierapolis, Irenaeus, Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria, Eusebius, Tertullian, and Origen—church fathers of the first two centuries of Christianity—all mention in their writings that Mark wrote his Gospels based on Peter’s eyewitness testimony and teachings. [2]

So folio 65v of Copte-Arabe 1 shows Peter passing on his intimate knowledge of Christ to Mark. As a sign of respect, Mark’s hands are covered with a cloth, ready to receive Peter’s notes.

Examining artistic precedents of this pair of men, Hunt writes:

Middle Byzantine iconographic sources can . . . be suggested for the Copte-Arabe 1 portrait of Mark with Peter (fol. 65v), which relates to the broad category of Evangelist portraiture with a second, usually inspiring figure. Mark appears seated, with Peter, who stands before him bearing the Gospel. More frequent are portraits of Peter dictating to Mark, the earliest known being that in the mutilated Greek New Testament in Baltimore (Walters Art Gallery W. 524) in which both are seated. Greek manuscripts with such portraits would have been accessible through the Syrian and Armenian communities. Two such twelfth century Gospels today in Jerusalem are the Greek Taphou 56 and the Armenian Theodore Gospels (Armenian Patr. 1796), showing the standing Peter dictating to the seated Mark. It has often been pointed out that secondary figures, either inspiring or presenting, are particularly common in Coptic and other oriental Christian art. [3]

Now let’s take a look at the narrative images. I went through them all and attempted to identify each scene as best I could (I can’t read the Arabic inscriptions), which I label in the caption along with the scripture passage it illustrates. These descriptive titles are preceded by the folio number. Note that in manuscript studies, “fol.” or “f.” stands for “folio” (page), “v” stands for “verso” (a left-hand page), and “r” stands for “recto” (a right-hand page).

All the image files are sourced from La bibliothèque numérique de l’Institut Catholique de Paris (The Digital Library of the Catholic Institute of Paris), which hosts a full scan of the manuscript. If you wish to reproduce any of the images singly, I suggest the following caption: Page from a Coptic-Arabic Gospel Book, Cairo, Egypt, 1249–50. Illuminations on parchment, 25.5 × 17.5 cm. Bibliothèque de Fels (Fels Library), Institut Catholique de Paris, Ms. Copte-Arabe 1, fol. _.

The first narrative scene in the manuscript, a header to the Gospel of Matthew, is a Nativity, with Mary reclining in the hollow of a cave and the Christ child lying swaddled beside her, adored by an ox and ass. An angel with folded hands peers reverently over a rocky outcrop, while shepherds approach from the left and magi from the right. Joseph is seated near his wife, eyeing the coming visitors.

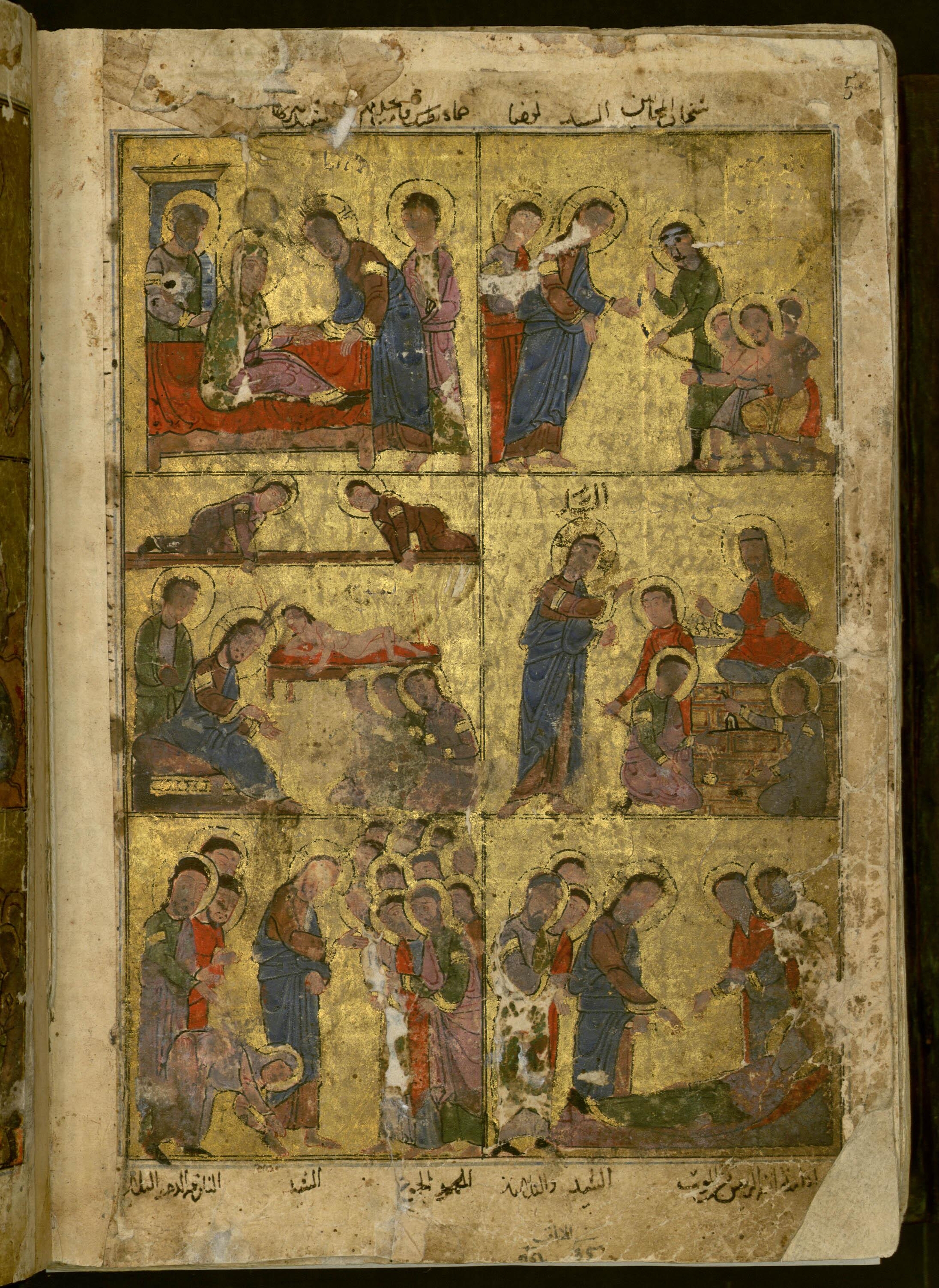

Later there follow six pages illuminating various stories from the Gospel of Matthew—the largest image sequence in the manuscript. As in the Gospels of Luke and John (there are none for Mark), these scenes are arranged on a grid system of six small squares to a page.

From having seen other similar compositions, I know that the man holding the scroll and gesturing toward the donkey on folio 19r/1 is the prophet Zechariah, and that his scroll contains a portion of Zechariah 9:9: “Rejoice greatly, O daughter Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter Jerusalem! See, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey.”

Strikingly, all the figures in this manuscript are given halos around their heads, not just holy figures—for example, King Herod, antagonistic Pharisees, Judas, the Roman soldiers who arrest and taunt Jesus, and the foolish virgins. I’m not sure the reason for this; it’s possible it marks the imago Dei in each and every human, even those who oppose Christ. I welcome the input of scholars better versed in Coptic art than I.

The headpiece to the Gospel of Mark portrays the Baptism of Christ. Fully nude, he is submerged in the Jordan River. John the Baptist stands on the bank and touches Christ’s head, while the hand of God the Father emerges from the heavens, pronouncing blessing over the Son, and the Holy Spirit as dove hovers above. Again, the manus velatae (veiled hands) motif appears, this time with the angels, signaling their reverence. On the left an ax cuts into the base of a tree, a reference to John the Baptist’s stark warning to the Sadducees and Pharisees who observe the baptisms: “Even now the ax is lying at the root of the trees; therefore every tree that does not bear good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire” (Matt. 3:10).

The next illumination is folio 106r, which opens the Gospel of Luke. It shows three scenes from Luke 1: the angel Gabriel announcing to the priest Zechariah that his wife, Elizabeth, will bear a son named John; Gabriel announcing to the virgin Mary that she will bear a son named Jesus; and Mary and Elizabeth rejoicing together in the unexpected news of their pregnancies and the divine deliverance they signal.

In the first full-page miniature from Luke (below), the third scene confuses me a bit. I’m fairly sure it’s supposed to be the twelve-year-old Jesus sitting among the doctors of the law in the temple at Jerusalem, as narrated in Luke 2:41–51; this episode is typically included in image cycles on the Life of Christ. But here he’s shown as a full-grown adult. The arch above the group is similar to the one shown in the previous frame where the infant Christ is presented in the temple forty days after his birth, suggesting that this is the temple, not a synagogue.

Regardless, the next episode, portrayed on folio 109v/4, is one of my favorites in Luke’s Gospel: Jesus interpreting the Isaiah scroll at his hometown synagogue, announcing himself as the long-awaited Messiah and thereby launching his ministry.

When he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, he went to the synagogue on the Sabbath day, as was his custom. He stood up to read, and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was given to him. He unrolled the scroll and found the place where it was written:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to set free those who are oppressed,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.And he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. The eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. Then he began to say to them, “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.” (Luke 4:16–20; cf. Isa. 61)

When asked to expound, Jesus emphasizes how God’s plan of salvation is for all people, recounting two stories from the Hebrew scriptures in which God showed favor to Gentiles—namely, the widow of Zarephath and the Syrian general Naaman. Well, this really raises the ire of his Jewish audience, who believed the Messiah should act exclusively on their behalf. The artist of Copte-Arabe 1 shows on folio 109v/5 the culmination of this contentious encounter between the up-and-coming Jewish teacher making his way through Galilee and the old guard: an attempted murder!

When they heard this, all in the synagogue were filled with rage. They got up, drove him out of the town, and led him to the brow of the hill on which their town was built, so that they might hurl him off the cliff. But he passed through the midst of them and went on his way. (Luke 4:28–30)

On the following page, in the fifth frame, the Rich Man and Lazarus is one of Jesus’s three parables depicted in the manuscript. (The other two are of the Ten Virgins and the Good Samaritan.) The artist depicts not the impoverished, sore-laden Lazarus begging outside the wealthy Dives’s door in this life, but the afterlife. Lazarus, now whole, sits comfortably in Abraham’s bosom, while Dives, who lacked mercy on earth, is denied it in hell; he languishes in flames.

I’m not sure what the center right scene depicts, but given its placement in the sequence, its setting in a lavish interior, and Jesus’s clear presence at the left (as indicated by the cross in his halo; which I’d say precludes the figures being characters in a parable), my best guess is it represents the healing of the man with edema (dropsy), which takes place in the house of a prominent Pharisee.

Further into the manuscript, our anonymous artist commences the fourth and final Gospel, John, with a depiction of the descent of the Holy Spirit on the apostles at Pentecost—an event described not in John’s Gospel but in the book of Acts.

Folio 179r also contains scenes whose scriptural referents are from other Gospels: four women arriving at Christ’s empty tomb on Easter morning (John mentions only Mary Magdalene, Matthew mentions two women, Mark mentions three, and Luke speaks generally of “the women”); the risen Christ meeting two pilgrims on the road to Emmaus; and Christ’s ascent into heaven. I suppose it’s because this final full-page miniature is Resurrection-themed, so the artist harmonizes the four Gospels, pulling relevant highlights from each.

NOTES

1. Lucy-Anne Hunt, “Christian-Muslim Relations in Painting in Egypt of the Twelfth to Mid-Thirteenth Centuries: Sources of Wallpainting at Deir es-Suriani and the Illustration of the New Testament MS Paris, Copte-Arabe 1 / Cairo Bibl. 94,” Cahiers Archéologiques 33 (1985): 111–55, here 111. Reprinted in Lucy-Anne Hunt, Byzantium, Eastern Christendom and Islam: Art at the Crossroads of the Medieval Mediterranean, vol. 1 (London: Pindar, 1998): 205–81.

2. J. Warner Wallace, “Is Mark’s Gospel an Early Memoir of the Apostle Peter?,” Cold-Case Christianity, July 25, 2018.

3. Hunt, “Christian-Muslim Relations,” 129.