SPOTIFY PLAYLIST: August 2025 (Art & Theology)

+++

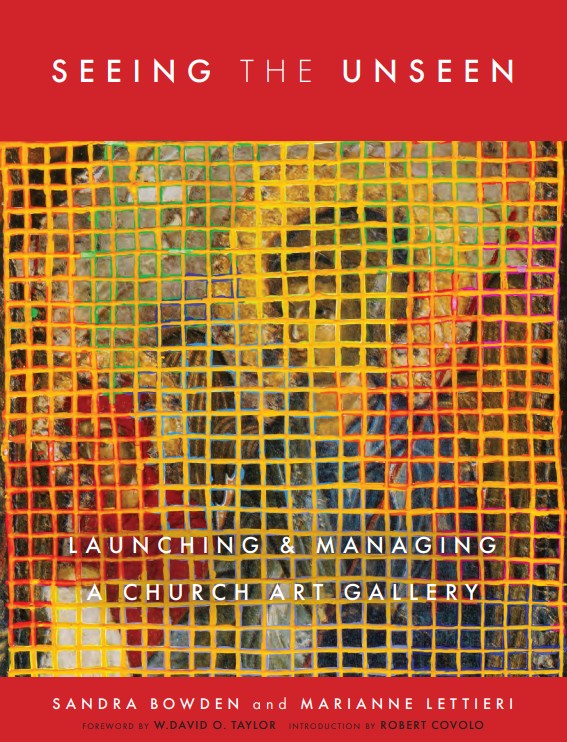

FREE E-BOOK: Seeing the Unseen: Launching and Managing a Church Art Gallery by Sandra Bowden and Marianne Lettieri: I own a copy of the original 2015 edition of this book written by two wise, experienced friends of mine and published by the now-defunct Christians in the Visual Arts; this revised edition, published this year by Square Halo Books, includes all-new images and other updates. It’s an excellent resource for churches looking to start an art gallery, covering the logistics of defining the gallery program, designing the gallery space, funding the gallery, organizing exhibits and juried shows, handling art, engaging viewers, and more. The authors and publisher are generously making it available for free download!

+++

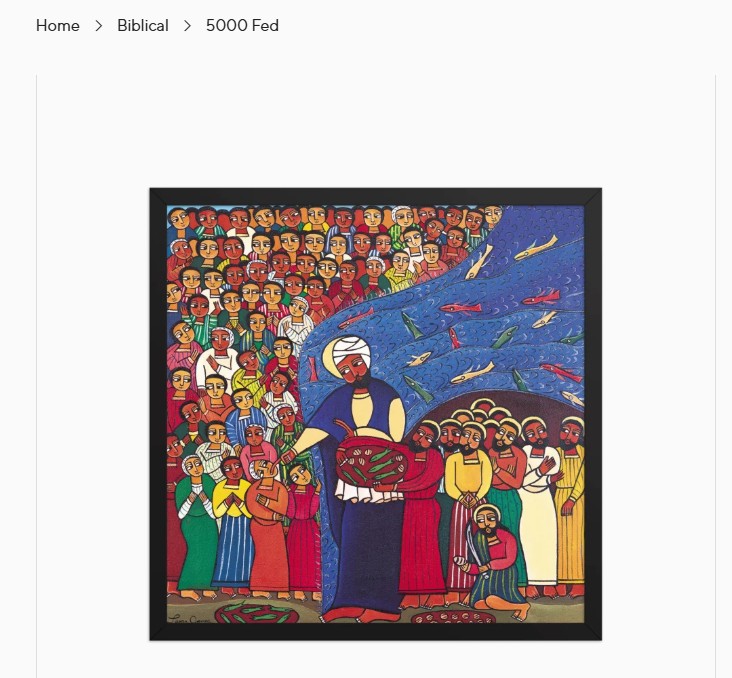

New this summer, the popular artist Laura James [previously], who frequently paints biblical subjects, now has a simple form on her website through which you can license digital image files of hers for use in publications, presentations, or websites: https://shop.laurajamesart.com/product/image-licensing/.

Also, folks often ask me where they can purchase affordable art: Check out James’s online store, as she sells giclée prints of many of her paintings.

+++

ESSAY: “Toward a Genuine Dialogue between the Bible and Art” by J. Cheryl Exum: J. Cheryl Exum (1946–2024) was a Hebrew Bible scholar renowned for her work on the Song of Songs, feminist biblical studies, and the reception of the Bible in culture and art history. In much of her writing and teaching she staged a dialogue between biblical texts and biblical art, the latter of which, she said, constitutes a form of exegesis. She argued “for adding visual criticism to other criticisms (historical, literary, form, rhetorical, etc.) in the exegete’s toolbox—for making visual criticism part of the exegetical process, so that, in biblical interpretation, we do not just look at the text and the commentaries on the text but also at art as commentary.” More than simply enhancing our appreciation of a biblical text, art “can point to problematic aspects of the text and help us ‘see’ things about the text we might have overlooked, or enable us to see things differently.”

In this paper from 2012, Exum examines two episodes from the life of Hagar: the Expulsion of Hagar and Ishamel (Gen. 21:8–14), and Sarah Presenting Hagar to Abraham (Gen. 16:3–4). I found the second section particularly illuminating in how it addresses a narrative gap in Genesis 16, which is Hagar’s being raped (made to have sex without her consent) by Abraham at Sarah’s behest. Customary in many ancient patriarchal societies, the use of slaves to bear children for one’s family line is what is dramatized in the popular novel-turned-TV series The Handmaid’s Tale. Exum looks at six seventeenth-century paintings of Sarah leading a reluctant and sometimes humiliated Hagar, who tries in vain to cover her nakedness, into Abraham’s bed. “These paintings,” Exum writes, “require us to consider what assumptions about women and slaves and their rights to their bodies lie behind the biblical narrator’s simple ‘he went in to her and she conceived’, assumptions commentators too readily ignore.”

In the final section of the paper, Exum considers a disturbing verse in the Song of Songs that has stumped commentators but that the artist Gustave Moreau chose to visually interpret.

+++

POEM: “He Who Sees Hagar” by Michelle Chin: “She buys me for my birth canal / but beats me for the birth. / I despise her . . .” Published in Reformed Journal.

+++

VIDEO SERIES: Dramatic Encounters (proof of concept pilot), created by Martin J. Young: Martin J. Young, a UK-based speaker, writer, and mentor to church leaders and creatives, is developing a film series with writer-director Ethan Milner of Cedar Creative that explores people’s dramatic encounters with Jesus in John’s Gospel. Inspired in part by David Ford’s The Gospel of John: A Theological Commentary (Baker Academic, 2021), the series will adapt particular gospel stories to screen and, uniquely, will include a documentary component that highlights the creative process from start to finish.

Each episode will consist of four primary elements (expanded from the three showcased in the pilot):

- The Roundtable, a conversation with theologians, pastors, and artists about the given gospel story, examining its form, meaning, themes, and interpretations

- The Rehearsal, in which the actors, informed by the roundtable discussion, work out how to perform the story, choosing facial expressions, postures and movements, vocal tones and inflections

- Behind-the-Scenes, exploring the various cinematographic choices made by Milner and his filmmaking team (e.g., sets, lighting, framing, editing, scoring)

- The Film, a roughly ten-minute drama that brings the gospel story to life

The proof of concept pilot episode below is based on John 12:1–8, in which Mary of Bethany anoints Jesus with expensive perfume, much to Judas’s chagrin. The short starts at 24:13. I’m impressed by the quality! And the “voyage of discovery” approach of the overall episode—wrestling with scripture in preparation for inhabiting its characters, and translating it into a filmic narrative—pays off, as viewers are granted insight into the crafts of acting, filmmaking, and literary adaptation.

Young is seeking funding to produce and distribute a season of eight to ten episodes. (None have been made yet.) If you’re interested in helping out financially, visit https://www.cedarcreative.net/encounters, and click “Donate Today.” Explore more at https://this-is-that.com/.