I’m late in notifying you about my June 2025 playlist (a random compilation of faith-inspired songs I’ve been enjoying lately), but be sure to check it out on Spotify.

See also my Juneteenth Playlist, which I’ve added six new songs to since originally releasing it two years ago, including a cover of Roberta Slavitt’s protest song “Freedom Is a Constant Struggle,” “Black Gold” by Esperanza Spalding, and “The Block” by Carlos Simon, a short orchestral work based on a six-panel collage by Romare Bearden celebrating Harlem street life.

+++

PODCAST EPISODE: “The Body as Sacred Offering: Ballet and Embodied Faith” with Silas Farley, For the Life of the World, April 30, 2025: An excellent interview! “Silas Farley, former New York City Ballet dancer and current Dean of the Colburn School’s Trudl Zipper Dance Institute, explores the profound connections between classical ballet, Christian worship, and embodied spirituality. From his early exposure to liturgical dance in a charismatic Lutheran church to his career as a professional dancer and choreographer, Farley illuminates how the physicality of ballet can express deep spiritual truths and serve as an act of worship.”

I was especially compelled by Farley’s discussion of turnout, the rotation of the leg at the hips—foundational to ballet technique. It gives the body an “exalted carriage” and allows for “a more complete revelation of the body,” he says, because you see more of the leg’s musculature that way. This physical positioning, he says, reflects the correlative “spiritual turnout” that’s also happening in dance, and that Christians are called to in life—a posture of openness and giving. He cites the theological concept of incurvatus in se, coined by Augustine and further developed by Martin Luther, which refers to how sin curves one in on oneself instead of turning one outward toward God and others.

Farley also discusses how liturgical dance is like and unlike more performative modes of dance (“liturgical dance . . . is a kind of embodied prayer . . . a movement that goes up to God out of the body”); how discipline and freedom go together; the body as instrument, and how dancers cultivate a hyperawareness of their bodies; the two basic design elements of ballet, the plié and the tendu, and their significance; his formation, from ages fourteen to twenty-six, under the teaching of Rev. Dr. Tim Keller at Redeemer Presbyterian Church; the Four Loves ballet he choreographed on commission for the Houston Ballet, based on a C. S. Lewis book (see promo video below, and his and composer Kyle Werner’s recent in-depth discussion about it for the C. S. Lewis Foundation); Songs from the Spirit, a ballet commissioned from him by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see next roundup item); Jewels by George Balanchine, a three-act ballet featuring three distinct neoclassical styles; “Hear the Dance” episodes of City Ballet the Podcast, which he hosts; and book recommendations for kids and adults.

+++

SITE-SPECIFIC BALLET: Songs from the Spirit, choreographed by Silas Farley: Commissioned by MetLiveArts [previously], Songs from the Spirit by Silas Farley is a three-part ballet for seven dancers that interprets old and new Christian spirituals, having grown out of an offertory Farley gave at Redeemer Presbyterian Church based on the song “Guide My Feet, Lord.” Staged in the museum’s Assyrian Sculpture Court, the Astor Chinese Garden Court, and the glass-covered Charles Engelhard Court of the American Wing, the ballet progresses from “Lamentation” to “Contemplation” to “Celebration.” Here’s a full recording of the March 8, 2019, premiere:

For the project, Farley solicited new “songs (and spoken word poetry) from the spirit” from men who were currently or formerly incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison in California, whose creative talent he learned about through the Ear Hustle podcast. Recordings of these contributions form about half the score, while the other half consists of traditional spirituals sung live by soprano Kelly Griffin and tenor Robert May. My favorite section is probably “Deep River” at 26:54, a duet danced by Farley and Taylor Stanley, picturing a soul’s “crossing over” to the other side, supported by an angelic or divine presence, or perhaps one who’s gone before.

In his artistic statement, Farley says he wanted to invite viewers “to accompany us [dancers] on this journey: from darkness to light, bondage to freedom, exile to home.”

I am struck by how a contemporary work that is, in Farley’s words, so “unequivocally Christ-focused and Christ-exalting” was welcomed, even made financially possible, by a prestigious secular institution. I find apt Farley’s response when asked by Macie Bridge from the Yale Center for Faith & Culture about his consideration of his audiences (see previous roundup item):

All the people coming to the performance are hungry in different ways. Some are longing for beauty. Some are longing for a prophetic image of a better world. Some are longing to see something reflected back to them from their own lives. And I’m just trusting that as I offer the artwork as an act hospitality, and as I offer the artwork as an act of adoration and worship back to God, that in his own beautiful, winsome, totally personalized way, he’ll meet each of the audience members in the way they need to be met.

+++

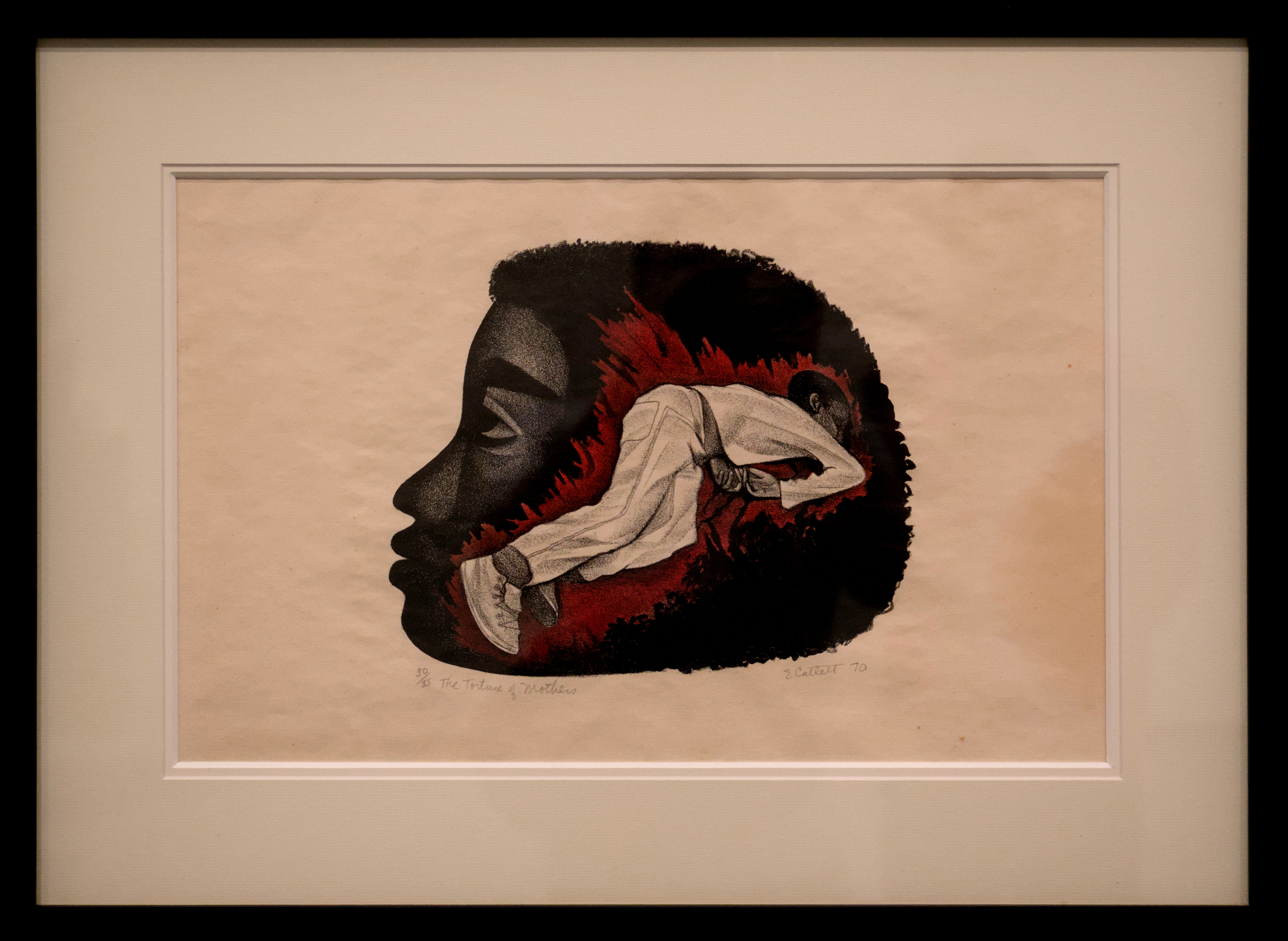

ARTWORK: Dreaming with the Ancestors by Charlie Watts and Tricia Hersey [HT: Visual Commentary on Scripture]: Tricia Hersey is a poet, performance artist, spiritual director, and community organizer living in Atlanta, Georgia. She is the founder of The Nap Ministry, an organization that promotes rest as a form of resistance against capitalism (which fuels contemporary grind culture) and white supremacy, and the author of the New York Times best-selling Rest Is Resistance: A Manifesto (2022) and We Will Rest! The Art of Escape (2024). She pursued graduate research in Black liberation theology, womanism, somatics, and cultural trauma, earning a master of divinity degree from Candler School of Theology at Emory University.

The photograph Dreaming with the Ancestors, taken by Charlie Watts, portrays Hersey reclining on a wooden bench inside an open brick enclosure and above rows of cotton plants. Dressed in a soft yellow gown, she closes her eyes in rest, practicing what she calls “the art of escape”—from the incessant demand of productivity and overwork, from oppression of body and spirit, from noise that drowns out voices of wisdom.

In We Will Rest!, Hersey advises:

Every day, morning or night, or whenever you can steal away, find silence. Even if for only a few minutes. Look for quiet time, quiet breathing, quiet wind, quiet air. It is there. Even if it’s cultivated in your body by syncing with your own heart beating. Guilt and shame will be a formidable and likely opponent in your resistance. We expect guilt and shame to surface. Let them come. We rest through it. We commit to our subversive stunts of silence, truth, daydreaming, community care, naps, sleep, play, leisure, boundaries, and space. Be passionate about escape. (107)

+++

ALBUM: Grace Will Lead Me Home by Invisible Folk (2024) [HT: Jonathan Evens]: An Arts Council England grant awarded to singer-songwriter Jon Bickley in 2022 enabled him to conduct a research and songwriting project that culminated in the album Grace Will Lead Me Home, which engages with the hymn “Amazing Grace,” its author’s biography, and its legacy. Bickley partnered with the Cowper and Newton Museum in Olney and enlisted the collaboration of fellow folk musicians Angeline Morrison (The Sorrow Songs: Folk Songs of Black British Experience) and Cohen Braithwaite-Kilcoyne (creator of the “Black Singers and Folk Ballads” resource for secondary educators, and concertina player on Reg Meuross’s Stolen from God). Here’s the title track, written and sung by Morrison:

The album also includes a cover of Zoe Mulford’s “The President Sang Amazing Grace,” written in response to the racially motivated mass shooting at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, on June 17, 2015 (its ten-year anniversary is next Tuesday). In his eulogy at the funeral of one of the nine victims, Rev. Clementa Pinckney, President Barack Obama chose “the power of God’s grace” as his theme, and he closed by singing the first stanza of “Amazing Grace,” a moving gesture that Mulford’s song remembers.

Other songs on Grace Will Lead Me Home address John Newton’s love for his wife Polly, his impressment into naval service, and his friendship with William Cowper. There are also songs that grapple with the harm and suffering Newton inflicted on others through his involvement in the slave trade, and that wonder at his hymn’s being so mightily embraced not only by the Black church, many of whose members are descendants of enslaved Africans, but also by other traumatized communities, who insist amid all the wrongs and afflictions they’ve suffered that God is amazingly gracious.

It’s a myth that John Newton (1725–1807), who converted to Christianity in 1748 after surviving a turbulent sea voyage, immediately gave up his employment as a slave trader upon embracing Christ. In fact, he was soon after promoted from slave ship crew member to captain and sailed three more voyages to Africa as such, trafficking human beings for profit until 1754, when his ill health forced him to retire. But he continued to invest in slaving operations for another decade, until becoming a priest in the Church of England. It wasn’t until 1788, in the pamphlet Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade, that he publicly denounced slavery and confessed his sin of having participated in that evil institution, and this was the start of his abolitionism.

+++

SONG: “Amazing Grace,” performed by the Good Shepherd Collective: This adaptation of “Amazing Grace” premiered at Good Shepherd New York’s digital worship service on June 1. Listen via the Instagram video below, or cued up on YouTube. The vocalists are, from right to left, Charles Jones on lead, Solomon Dorsey (also on bass), Jon Seale, Dee Wilson, and Aaron Wesley. James McAlister is on drums, Michael Gungor is on electric guitar, and Tyler Chester is on keys.