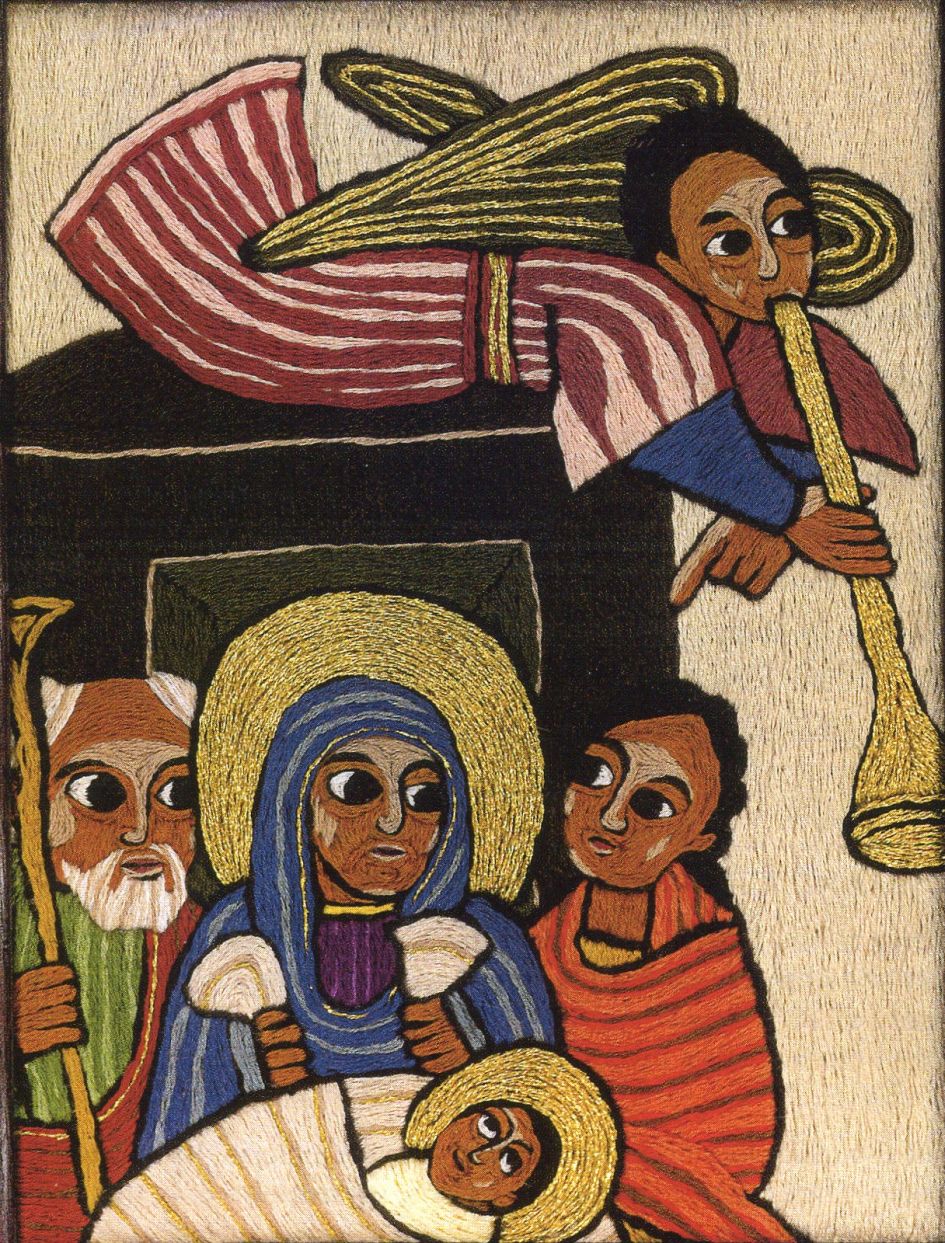

LOOK: Cristo nace cada día by Pablo Sanaguano

In this celebratory painting with elements of the surreal, the birth of Christ is transplanted to Chimborazo province in the Andean highlands of Ecuador, where artist Pablo Sanaguano lives. Light spills from a giant overturned jug (which doubles as the cave of the Nativity), spotlighting the newborn child who is held aloft by his proud parents, Mary and Joseph. Summoned by a bocina (horn), villagers come bearing corn, potatoes, and other gifts from their harvest, while others play instruments—a bamboo panpipe, a quena (flute), a bomba (drum). The “angels” flying overhead are men in mythical bird costumes.

LISTEN: “Todos los días nace el Señor” by Juan Antonio Espinoza, 1976 | Performed by musicians at Iglesia Presbiteriana Comunidad de Esperanza (Community of Hope Presbyterian Church), Bogotá, Colombia, 2020

Para esta tierra sin luz, nace el Señor;

para vencer las tinieblas, nace el Señor;

para cambiar nuestro mundo,

todos los días nace el Señor.

Para traer libertad, nace el Señor;

nuestras cadenas rompiendo, nace el Señor;

en la persona que es libre,

todos los días nace el Señor.

Para quitar la opresión, nace el Señor;

para borrar la injusticia, nace el Señor;

en cada pueblo que gime,

todos los días nace el Señor.

Para vencer la pobreza, nace el Señor;

para los pobres que sufren, nace el Señor;

por la igualdad de las gentes,

todos los días nace el Señor.

Para traernos la paz, nace el Señor;

para esta tierra que sangra, nace el Señor;

en cada pueblo que lucha,

todos los días nace el Señor.

Para traernos amor, nace el Señor;

para vencer egoísmos, nace el Señor;

al estrechar nuestras manos,

todos los días nace el Señor.

Para este mundo dormido, nace el Señor;

para inquietar nuestras vidas, nace el Señor;

en cada nueva esperanza,

todos los días nace el Señor.

English translation:

Into a world without light, Jesus Christ is born.

Coming to conquer the darkness, Jesus Christ is born.

He comes to bring us a new world.

Jesus our Lord is born every day!

Freedom is coming to all, Jesus Christ is born.

Chains of oppression are breaking, Jesus Christ is born.

Liberating all of God’s children,

Jesus our Lord is born every day!

Justice is coming to all, Jesus Christ is born.

There will be no more oppression, Jesus Christ is born.

He hears the cry of his people.

Jesus our Lord is born every day!

He is the friend of the poor, Jesus Christ is born.

He brings hope to all who suffer, Jesus Christ is born.

Earth’s fruits are for all who labor.

Jesus our Lord is born every day!

He comes to bring us his peace, Jesus Christ is born.

Where there is strife, blood, and hatred, Jesus Christ is born.

Wherever his people are struggling,

Jesus our Lord is born every day!

He comes to teach us to love, Jesus Christ is born.

Throw off the shackles of hatred, Jesus Christ is born.

Join hands, sisters and brothers!

Jesus our Lord is born every day!

He wakes the world from its sleep, Jesus Christ is born.

He stirs and calls us to action, Jesus Christ is born.

In every heart that is hopeful,

Jesus our Lord is born every day! [1]

This contemporary Venezuelan carol is popular throughout Latin America. Its title and refrain translate to “Jesus our Lord is born every day!” This declaration does not dehistoricize the birth, but rather extends it. In what sense is Christ born every day? In the hearts and communities of those who embrace him.

The medieval German mystic Meister Eckhart once preached on Christmas Day,

Here, in time, we are celebrating the eternal birth which God the Father bore and bears unceasingly in eternity, because this same birth is now born in time, in human nature. St. Augustine says, “What does it avail me that this birth is always happening, if it does not happen in me? That it should happen in me is what matters.” We shall therefore speak of this birth, of how it may take place in us and be consummated in the virtuous soul, whenever God the Father speaks His eternal Word in the perfect soul. [2]

NOTES

1. English translation by Alvin Schutmaat, in Hans-Ruedi Weber, Immanuel: The Coming of Jesus in Art and the Bible (Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1984), 92.

2. Meister Eckhart, Dum medium silentium, Sermon on Wisdom 18:14–15, in The Complete Mystical Works of Meister Eckhart, trans. and ed. Maurice O’C. Walshe, rev. Bernard McGinn (New York: Herder & Herder: 2009), 29. The quote by Augustine is untraced. (Eckhart’s quotations from authorities are often free, from memory, and thus difficult to verify.)

This post is part of a daily Christmas series that goes through January 6. View all the posts here, and the accompanying Spotify playlist here.