mother emanuel ame church, charleston, sc, 1822: cross-ankle church, palmetto, ga, 1899: green leaf presbyterian church, keeling, tn, 1900: red top church, hopkinsville, ky, 1915: first baptist church, carteret, nj, 1926

Fisk Jubilee Proclamation

(choral)

O sing unto the Lord a new song . . . (Psalm 96)

O, sing . . . undo the world with blued song born from newly freed throats. Sprung loose from lungs once bound within bonded skin. Scored from dawn to dusk with coffle and lash. Every tongue unfurled as the body’s flag. Every breath conjured despite loss we’ve had. Bear witness to the birthing of our hymn from storied depths of America’s sin. Soul-worn psalms, blessed in our blood through dark lessons of the past struggling to be heard. Behold—the bold sound we’ve found in ourselves that was hidden, cast out of the garden of freedom. It’s loud and unbeaten, then soft as a newborn’s face— each note bursting loose from human bondage.

Fulton Street M.E. Church, Chicago, IL, 1927: Second Baptist Church, Detroit, MI, 1930: Macedonia Baptist Church, Egg Harbor City, NJ, 1935: Mount Methodist Church, Henderson, NC, 1940: Negro Methodist Church, Loganville, GA, 1947

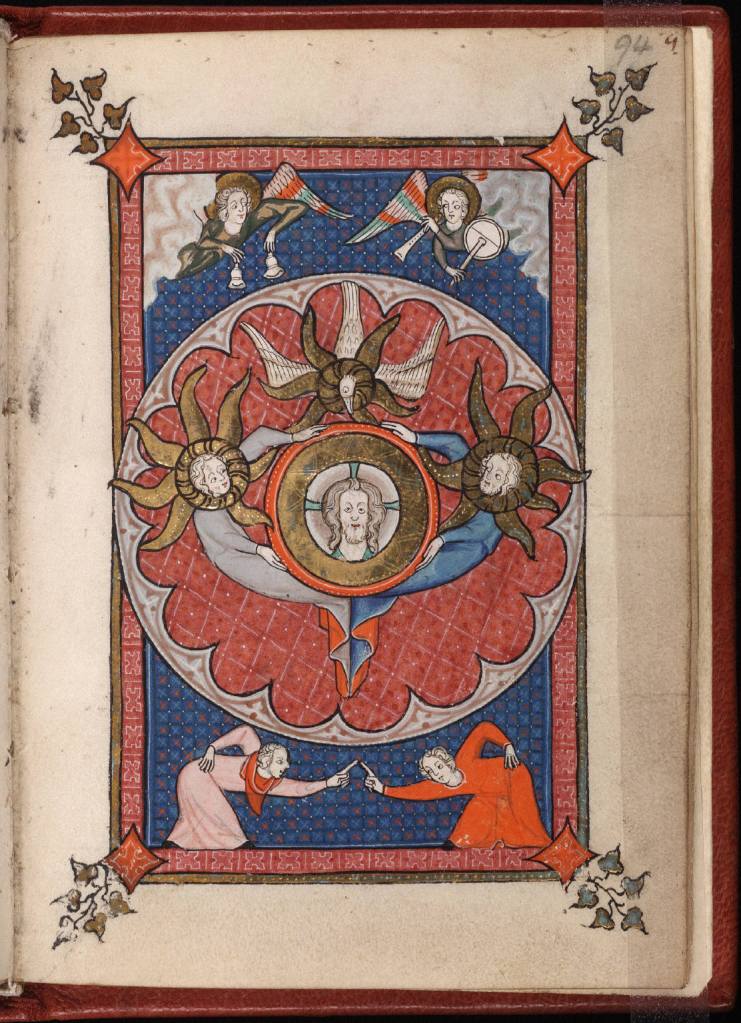

Source: Olio by Tyehimba Jess (Seattle and New York: Wave Books, 2016). Illustration by Jessica Lynne Brown, from Olio, p. 5. Used with permission. View the book page.

Hear Tyehimba Jess introduce and read his poem at the New York State Writers Institute in this video from 2017:

“Fisk Jubilee Proclamation” by Tyehimba Jess is the first in a heroic crown of sonnets from Jess’s second poetry collection, the Pulitzer Prize–winning Olio. A crown of sonnets is a circular sequence in which the last line of the first sonnet becomes the first line of the second sonnet, the last line of the second sonnet becomes the first line of the third sonnet, and so forth, until eventually the last line of the last sonnet becomes the first line of the first sonnet. What makes Jess’s crown “heroic” (part of the form’s technical name) is that it comprises fifteen sonnets, and the final one is made up of all the first or last lines of the preceding fourteen, in order. Quite the feat!

With this heroic crown, Jess honors the Fisk Jubilee Singers from the historically Black Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, a choral ensemble established in 1871 and still active today. Fisk was founded after the Civil War to educate freed men and women and other young African Americans. To raise money for the new school, music professor and treasurer George L. White formed a small choir of nine students to tour the United States. Their repertoire was the spirituals they and their parents sang on the plantations, songs that were rarely known at the time among northern white audiences—such as “Go Down, Moses,” “Steal Away to Jesus,” “Ezekiel Saw the Wheel,” “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho,” and “Roll, Jordan, Roll,” to name a few. The Fisk Jubilee Singers are credited with spreading and popularizing this uniquely Black American art form over the country and world.

Their first eighteen-month stint took them to Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Maryland, and Washington, DC. Then in 1873, they toured Great Britain and continental Europe, performing for Queen Victoria and other prominent figures.

The name of the group comes from Leviticus 25, where God mandates that every fifty years, the enslaved are to be set free: “And you shall hallow the fiftieth year, and you shall proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a Jubilee for you: you shall return, every one of you, to your property and every one of you to your family” (v. 10).

The Fisk Jubilee Singers took up God’s call to proclaim liberty far and wide, and they did so through their song. Written in the singers’ collective voice (hence the “choral” headnote), “Fisk Jubilee Proclamation” opens with an epigraph taken from Psalm 96:1: “O sing unto the Lord a new song . . .” (emphasis mine). The first line plays upon this biblical line by substituting three words that rhyme with the ones displaced: “O, sing . . . undo the world with blued song.”

Their song is blued because it was born out of deep suffering. And with it they undo the world—they open up those who were formerly closed off against them. They unravel racist stereotypes, asserting their sacred humanity.

They sing as an act of defiance. Whereas their enslavers had demanded them and their parents to be quiet and would often beat them into submission, now they are unapologetically loud, unbeaten—their words, like them, set free. They own their voices, which embody a range of nuance, from strong, vigorous, and sharp to soft and smooth. Tongue-tied no more, they burst loose from bondage with their new song of freedom. An unfurling of their body’s flag.

The poem is full of b alliteration: blued, born, bound, bonded, body’s, breath, bear, birthing, blessed, blood, behold, bold, (un)beaten, bursting, bondage. This letter is what’s known as a plosive consonant, because it makes a small explosive sound as you say it. Such an effect reinforces the idea of eruption.

Jess describes the choir’s singing as an act of childbirth, the hymn that has lain within them finally emerging, through painful labor, for all to hear. That hymn is “scored”—in the sense of its music being written on the page, but also bearing the marks of the slaver’s lash, that trauma, that story of violence and oppression, passed down to new generations. The “worn” in “soul-worn psalms” also has a double meaning, in that the singers wear their souls on the sleeves of their songs (or, the songs are dressed in soul) but also they are soul-weary.

Concurrent with the rise and ongoing performances of the Fisk Jubilee Singers were frequent attacks on Black places of worship. As the singers were spreading beauty and hope through the spirituals, white terrorists were spreading ugliness and hate. To remind readers of this context, Jess provides a litany of church names and dates across the top and bottom of the page of each Fisk Jubilee sonnet, indicating Black churches that were burned down, bombed, or sites of other kinds of racially motivated violence. In the back of the book Jess includes this note “On the Fisk Jubilee Choir testifying through fire . . .”:

The names of our burned and bombed black churches enfold the spirituals sung by our Jubilee choir. Inside each flame burns hum, prayer, and holy book. Each hymn inhabits heat and smolder; each biblical spark is kindled with story. There is no complete record of all such attacks upon the black congregational body, no complete accounting of all the pulpits, pews, and psalm books rendered into fire—these 148 stand in testimony to all the unnamed churches lost to arson and TNT, the slats and nails and sweat that doubled as schoolhouse and underground passageway, the pyres of pine and oak and cedar steeples that sheltered baptisms and home-goings, the silent crucifixions curled into ash. The AMEs and the Graces, the Tabernacles and all the many Firsts; the hand fans, tambourines, mourner’s benches, and collection plates; they rise in smoke like the songs that soaked through them and up to heaven’s blued, eternal door. (221)

The litany traces an unbroken line of violence from 1822 to 2015 and, true to the sonnet corona form, highlights a tragic circularity: Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, is the earliest African American church to suffer arson that Jess found record of in his research, and that same church was the target of a mass shooting on June 17, 2015, which claimed nine victims. (Tomorrow is the eighth anniversary.) This murder occurred while Olio was in production with the publisher, and Jess knew he had to add it to the end of the poem sequence.

Despite such assaults on their dignity and personhood, the Fisk Jubilee Singers have always continued to praise, and that is their glorious legacy. They’ve carried forward the joys, sorrows, and faith of their community in song. The final, extraordinary poem in Jess’s Fisk Jubilee sequence is titled “We’ve sung each free day like it’s salvation.” It ends like this: “We’ve smuggled faith from slave shack to palace, / boiling the air with hallelujah’s balm— / each note bursting loose from bondage / to sing unto the world a new song.”

I wholly commend Olio to you, which is the most inventive volume of poetry I’ve ever read. It took Jess nearly eight years to write, and given its irregular nature, I imagine it also took a while for the designer and production team at Wave Books to work out! An olio is a miscellaneous mixture of heterogenous elements, a hodgepodge, but also, as an early page of the book notes, “the second part of a minstrel show which featured a variety of performance acts and later evolved into vaudeville.”

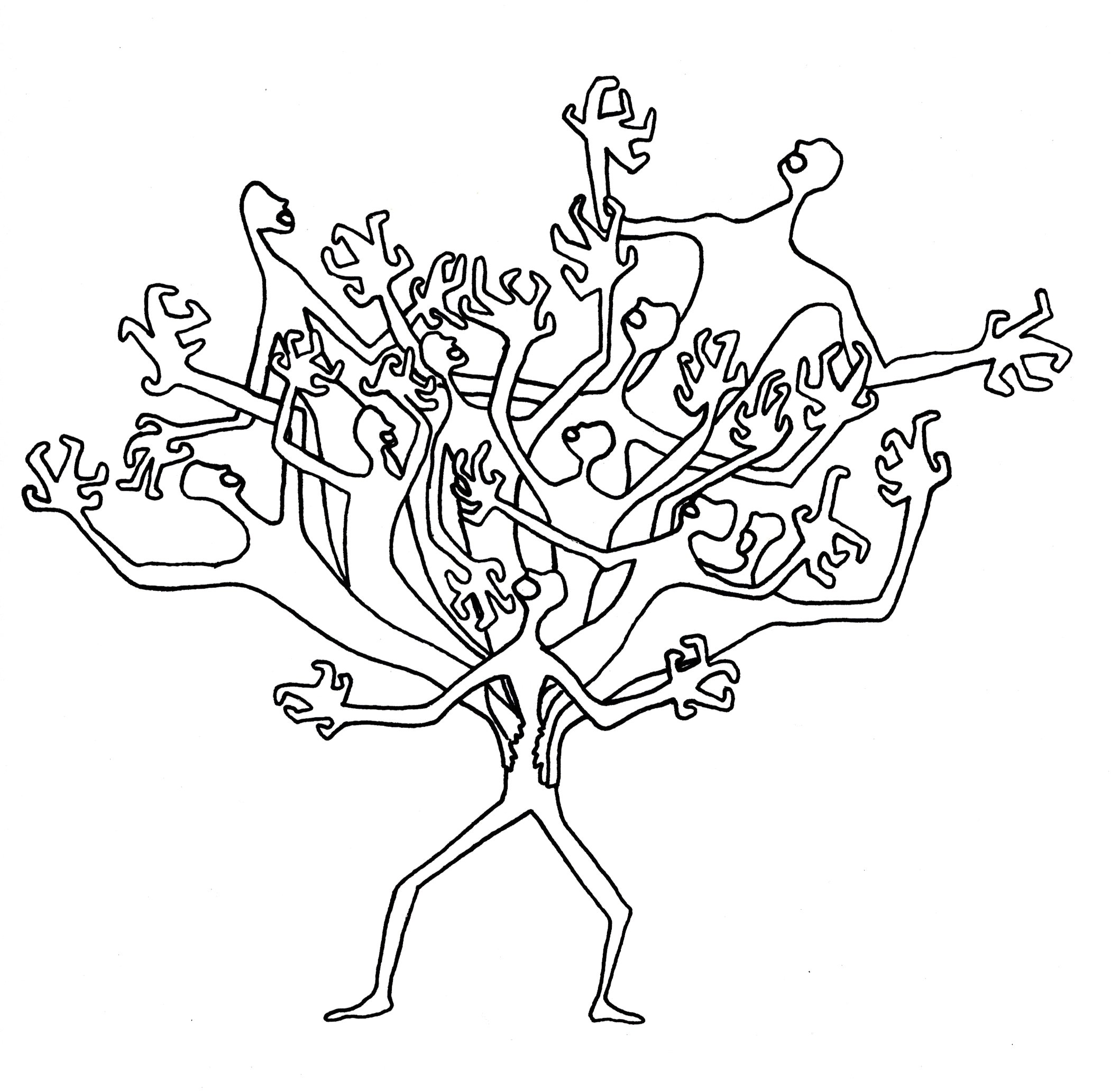

Part fact, part fiction, the book examines the lives of mostly unrecorded African American performers directly before and after the Civil War up to World War I, in “an effort to understand how they met, resisted, complicated, co-opted, and sometimes defeated attempts to minstrelize them,” as the publisher writes. It includes, for example, transcripts of interviews conducted by the fictitious Julius Monroe Trotter with an array of people who knew the ragtime composer Scott Joplin. It also includes syncopated sonnets (a form of contrapuntal poetry), which can be read up, down, diagonally, or interstitially—listen to Jess read and explain, for example, the sequence he wrote on the conjoined twins Millie and Christine McKoy, where the form stands in for the corpus of the sisters to represent their interconnected but independent narratives. But even for just the fifteen Fisk Jubilee sonnets alone, ten of which are in the voice of each of the original nine singers and their (white) conductor, the book is worth the price.

[Purchase Olio on Amazon] [Purchase Olio from Wave Books]

To learn more about what went into writing the Fisk Jubilee sonnets, read Jess’s blog post for the Poetry Foundation, “Flames of History / Rhythms of Song.” Also check out the interview with Jess published in the Interlochen Review, “Music, Literature, and the Struggle of Consciousness.” One thing that particularly stood out to me from the interview was, when asked about how he intertwines language and music in Olio, he said,

You have to remember in African American literature that we were deprived of the right of reading and writing for most of our history in this country. So, the song and the music became the literature. So, after emancipation, it’s impossible to really completely extract one from the other, because one was so instrumentally carrying so many stories for so long, for so many generations.

Tyehimba Jess (b. 1965) is a major poet whose work bridges slam and academic poetry and is imbued with deep archival research, often fusing music, history, and fiction. His first collection, leadbelly (2005), an exploration of the blues musician Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter’s life, was chosen for the National Poetry Series by Brigit Pegeen Kelly. His second collection, Olio (2016), which celebrates the mostly unrecorded Black musicians, orators, and other performers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize. He teaches English at the College of Staten Island.