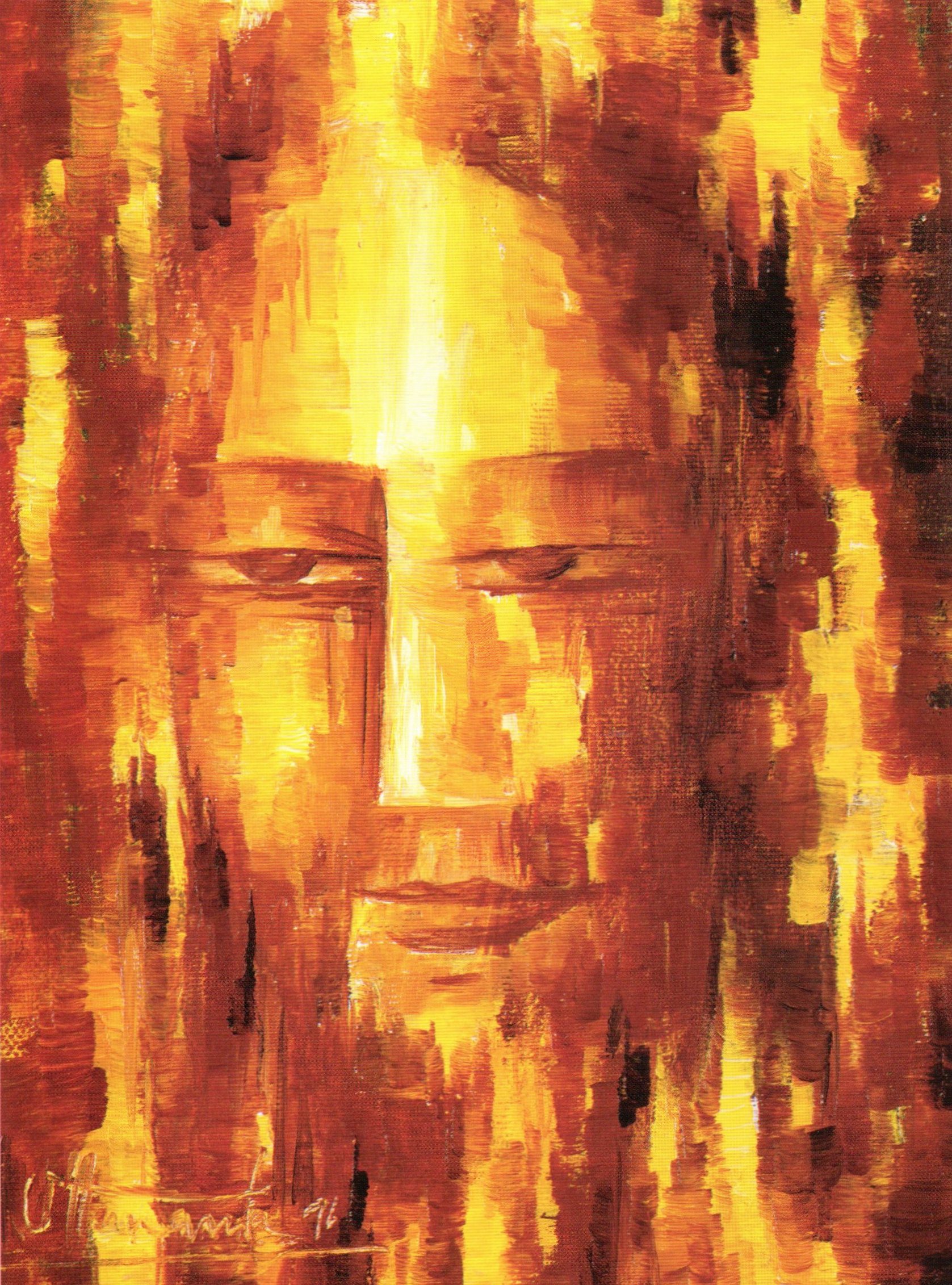

LOOK: The Wise and Foolish Virgins, Norwegian tapestry

The golden age of Norwegian tapestry (billedvev) spans roughly 1550 to 1800. Of all the woven subjects during this period, the Wise and Foolish Virgins was the most popular. The art historian Thor B. Kielland registered a total of seventy-five such tapestries from the seventeenth century alone. Draped over a bed, they would have provided warmth, decoration, and moral instruction. I love their aesthetic!

Jesus’s parable of the wise and foolish virgins comes from Matthew 25. Ten young women are members of a bridal party, and they’re awaiting the arrival of the bridegroom so that the celebration can start. In the tapestry pictured here, the top figures represent the wise virgins, whose oil-filled lamps indicate their readiness to accompany the bridegroom to the wedding feast. Those in the lower register, however, foolishly allowed their lamps to burn out; they weep into their handkerchiefs because the feasting started when they were out replenishing their oil supply, and now they’re too late.

That’s Christ the bridegroom in the upper right.

If I’m honest, this parable is uncomfortable for me. I don’t like that the neglectful women are locked out of the party. I don’t want anyone who wants in to be turned away. I want the bridegroom to show them grace, as the landowner did the day laborers who worked the vineyard for only one hour, giving them the same wage as those who worked for nine. But the parable of the virgins, with its stark sense of finality, is one of Christ’s teachings, so I want to grapple with it, not simply ignore it to suit my own proclivities.

I learned much about the existing body of Ten Virgins tapestries from rural Norway from Laura Berlage’s webinar “Dressing the Wise and Foolish Virgins: What Tapestry Can Teach Us About Women, Dress, and Culture in 16th and 17th Century Norway,” presented on July 17, 2023. She says the tapestries were made by women (unlike those produced by the guilds in Flanders and Paris), for women (they were used as bridal coverlets and included in dowries). They preached preparedness for young wives. “Good comes to those who are prepared,” Berlage elaborates; “you can’t get to heaven by borrowing someone else’s spiritual work.”

Regarding the headwear, Berlage clarifies: “The crowns the virgins wear are not because they’re princesses. There is a special tradition in Norway of wearing a crown at your wedding, which is an ancient nod to the Norse goddess Freja (later said to be an emblem of the Virgin Mary).”

Over time, Berlage says, the original meaning of the parable got lost, such that weavers no longer differentiated between the two sets of virgins, for example. She calls this phenomenon “image decay” and compares it to the telephone game.

For a shorter, less academic lesson on the ten virgins in Norwegian tapestry, see the six-minute video “Woven Wise and Foolish Virgins” by Robbie LaFleur:

LISTEN: “Himmelriket Liknas Vid Tio Jungfrur” (The Kingdom of Heaven Is Like Unto Ten Virgins) | Words from Then Swenska Psalmboken (The Swedish Hymnbook), 1697 | Traditional melody from Mockfjärd, collected by Nils Andersson in 1907 from Anders Frisell | Performed by Margareta Jonth on the album Religious Folk-Songs from Dalecarlia, 1977, reissued 1994

Himnelriket liknas vid tio jungfrur

som voro av olika kynne.

Fem månde oss visa vår tröga natur

Vårt sömnig och syndiga sinne.

Gud nåde oss syndare arma.

Vår brudgum drog bort uti främmande land

Och månde de jungfrur befalla

Sig möta med ljus och lampor i hand

Enär som han ville dem kalla.

De fävitske dröjde för länge.

De ropa: O Herre, o Herre låt opp,

Låt oss icke bliva utslutna!

Men ute var nåden, all väntan, allt hopp

Ty bliva de arma förskjutna

Till helvetets jämmer och pina.

Så låter oss vaka och hava det nit

Att tron och vår kärlek må brinna.

Vi måge här följa vår brudgum med flit

Och eviga salighet finna.

Det himmelska bröllopet. Amen.

The kingdom of heaven is like unto ten virgins

Who were of different character.

Five showed us our slothful nature,

Our sleepy and sinful selves.

God have mercy on us poor sinners.

Our bridegroom traveled in foreign lands

And ordered the virgins

To meet him with lighted lamp in hand

Whenever he called them.

The foolish ones waited too long.

They cry, “O Lord, O Lord, open up,

Let us not be locked out!”

But it was too late for mercy, for waiting, for hope,

For the poor souls were cast

Into hell’s wailing and torment.

So let us watch and show zeal

That faith and our love may burn.

Let us follow our bridegroom diligently

And find eternal bliss,

The heavenly wedding. Amen.

Trans. William Jewson (source: liner notes)