I didn’t post an Artful Devotion this week, as I struggled to satisfactorily put together image and song for any of the readings, but I’ve now cycled through all three lectionary years on the blog, which are stored in the archives. For content on Sunday’s lectionary reading from the psalms, Psalm 133, see “When Brothers Dwell in Unity (Artful Devotion)” (featuring a Chicago mural by William Walker and a joyful new psalm setting from the Psalter Project); see also the poem “Aaron’s Beard” by Eugene Peterson.

+++

NEW ALBUM: Quarantine Sessions by Eric Marshall: Eric Marshall is the frontman of and songwriter for the meditative art rock band Young Oceans. During the COVID-19 quarantine he recorded eleven of the band’s old songs acoustically in his home studio—just his voice and guitar—and has released them digitally on Bandcamp. Several music artists have been making stripped-down records during this season, and I’m digging it!

+++

ART COMMENTARIES from ART/S AND THEOLOGY AUSTRALIA

Art/s and Theology Australia is an online publication that aims to provoke public reflection and promote research on conversations between the arts and theology, predominantly in Australian contexts. Here are a few articles from the recent past that I particularly enjoyed.

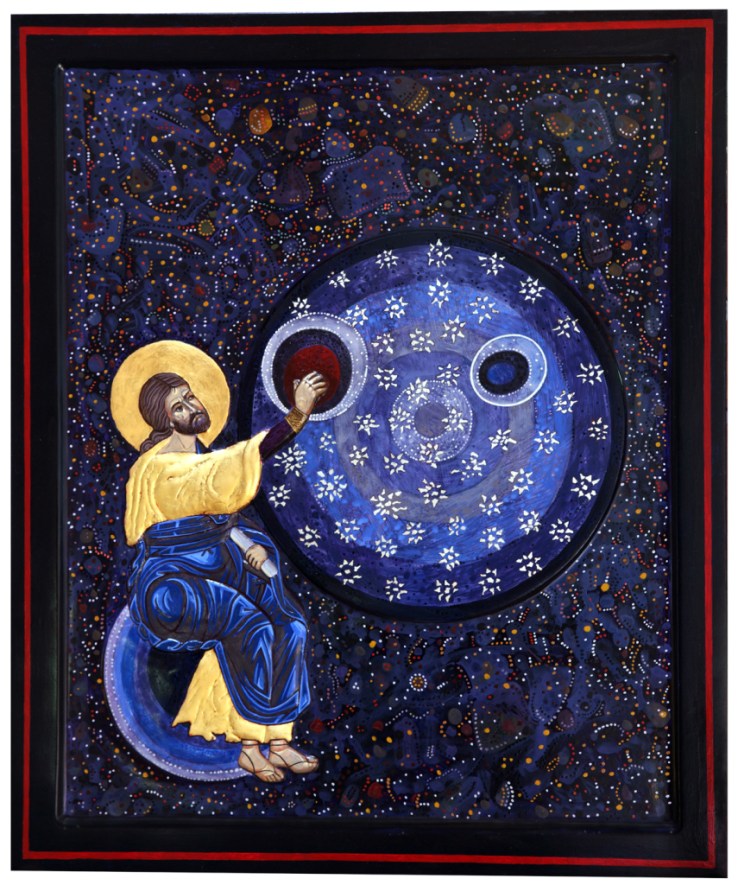

^^ “Jesus Dreaming: A Theological Reaction to Michael Galovic’s Creation of Lights in the Heavens” by Merv Duffy: Creation of Lights in the Heavens by contemporary artist and iconographer Michael Galovic is an authentically Australian reading and rewriting of one of the Byzantine creation mosaics at Monreale Cathedral. Like its visual referent, it shows the Logos-Christ seated on the cosmos, hanging the sun in place (medieval artists tended to show God the Son, who is depictable, as Creator), but the gold background, used in icons to represent the eternal uncreated light of God, is replaced with dots, curves, and circles that represent the Dreamtime of Aboriginal theology, the origin of time and eternity.

^^ “Sixteen Earth Bowls” by Penny Dunstan: Soil scientist and visual artist Penny Dunstan has crafted bowls out of topsoil from rehabilitated coal mines in the Hunter Valley in Warkworth, New South Wales, which she exhibits in churches, among other places. “Making earth bowls is a way of thinking about my ethical responses to soil use in a post-mining landscape,” she writes. “It is a way of thinking with my heart and not just my head. As I work with each Hunter Valley topsoil, I come to understand each as an individual, a special part of God’s creation. Each soil behaves according to its own chemical nature and historical past when I fashion it into a bowl shape. . . .

“These soils, full of tiny lives, are responsible for growing our food, making our air and storing atmospheric carbon. Our very lives as humans on the earth depend on them. By fashioning these soils into bowls and placing them in sacred places, I hope to remind us to honour the earth that we stand upon, that earth that speaks to us by pushing back at our feet.” (Note: See also Rod Pattenden’s ArtWay visual meditation on Dunstan’s work.)

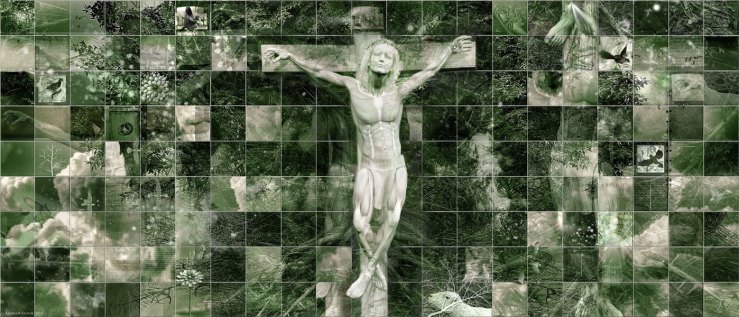

^^ “The Cross and the Tree of Life” by Rod Pattenden: “One of the pressing questions for the Church is how we see Christology being renewed in the face of climate change and the potential for the quality of life on this planet to decline,” writes art historian Rod Pattenden [previously]. “Who is Jesus for us in the midst of the profound changes that are occurring to the earth, water, and air of our world? . . .

“Andrew Finnie’s image The Body of Christ, The Tree of Life”—a large-scale ecotheological digital collage—“is an attempt to re-imagine the figure of Christ in conversation with the earth and the networks that sustain human life in all its thriving beauty. Here, the traditional figure of the cross has become entwined in the roots of the tree, a tree of life that is giving form to the variety and beauty of the natural world.”

+++

SONG: “Kadosh” by Wally Brath, sung by Nikki Lerner: The Kedushah is part of the Amidah, the central prayer of the Jewish liturgy. Its first verse is taken from the song of the seraphim in Isaiah 6:3: “Holy, holy, holy, is the LORD of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory!” (Kadosh means “holy.”) In this original composition for voice, piano, and string quartet, Wally Brath [previously] has combined this Hebrew exclamation from the book of the prophets with an English excerpt from the Lord’s Prayer taught by Jesus in Matthew 6:10: “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.” [HT: Multicultural Worship Leaders Network]

The performance captured in this video, featuring Nikki Lerner, took place at Winona Lake Grace Brethren Church in Winona Lake, Indiana, on July 11, 2020. A full list of performers is given in the YouTube description.

+++

CONCERT FILM: Amen! Music of the Black Church: Recorded before a live audience at the Second Baptist Church in Bloomington, Indiana, and airing April 26, this PBS special explores the rich traditions, historical significance, and meaning of black church music. Dr. Raymond Wise leads the Indiana University African American Choral Ensemble in twenty-one spirituals, hymns, and gospel songs, showing how black church music is not monolithic. He demonstrates the stylistic spectrum you can find among black church communities using a song text derived from Psalm 24:7–10 (“Lift up your heads . . .”): one performed with the European aesthetic preferred in more affluent congregations, one a classical-gospel hybrid, and one pure gospel. One thing I learned from the program is that there is a tradition of shape-note singing in the black church! (See, e.g., The Colored Sacred Harp.) [HT: Global Christian Worship]

Here’s the set list:

- “We’ve Come This Far by Faith” by Albert Goodson

- “Kumbaya”

- “Run, Mary, Run”

- “Oh Freedom”

- “What a Happy Time” by J. M. Henson and J. T. Cook

- “Amazing Grace” by John Newton

- “Ain’t Got Time to Die” by Hall Johnson

- “I’ve Been ’Buked”

- “Lift Up Your Heads” by Emma Louise Ashford, arr. Lani Smith

- “Lift Up Your Heads” by Clinton Hubert Utterbach

- “Lift Up Your Heads, All Ye Gates” by Raymond Wise

- “Glory, Glory, Hallelujah”

- “Jesus on the Mainline”

- “I Need Thee Every Hour” by Annie S. Hawks and Robert Lowry

- “You Can’t Beat God Giving” by Doris Akers

- “Come to Jesus” by E. R. Latta and J. H. Tenney

- “We Shall Overcome” by Charles Tindley

- “Lord, Keep Me Day by Day” by Eddie Williams

- “Lord, Do It for Me” by James Cleveland

- “Oh Happy Day” by Edwin Hawkins

- “I’ve Got a Robe” by Raymond Wise

- “Hallelujah, Praise the Lord, Amen” by Raymond Wise

+++

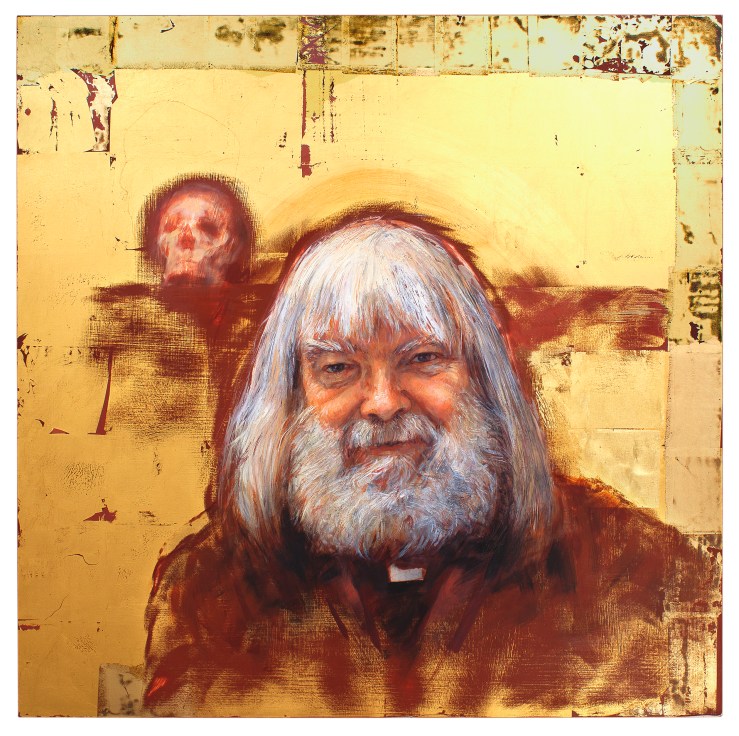

INTERVIEW: Last September The Cultivating Project interviewed Malcolm Guite [previously] on his latest poetry collection After Prayer, the poet-priest George Herbert, the life of a writer, art as faithful service, doubt and despair, his Ordinary Saints collaboration with Bruce Herman and J.A.C. Redford, his friendship with Michael Ward (author of Planet Narnia), the blessing of seasons (both earthly and liturgical), and making room for joy. The interview includes three of Guite’s poems: “Christ’s side-piercing spear,” “A Portrait of the Artist,” and “St. Augustine and the Reapers.”