“Translate: Art as Mission” symposium, February 25, 9 a.m.–3:30 p.m.: This Saturday, Third Church of Richmond, Virginia, is bringing together twenty practitioners, advocates, and theorists of the arts as front-line missions (both local and abroad) for a series of presentations and discussions that is free and open to the public. “Our aim is to demonstrate that ‘art as mission’ is not about using people and objects merely as ‘tools’ for missions or proselytization, but is about recognizing that generative, creative practices can and should be intrinsically, inherently ‘missional’ because they put on display and draw people towards the rich, abundant life we were made to experience and have together as God’s children, renewed as the Body of Christ. Together we’ll explore how the arts are a distinctively integrative, incarnational way to be human, and to bear the image of our creator God.” Click on the link to see the schedule and to find out more about the speakers.

+++

“Charged with the Grandeur of God: Faithful Imaginations in a Meaningful Creation” lecture, February 25, 7–9 p.m.: Also on Saturday, Ken Myers, founder and host of Mars Hill Audio and author of All God’s Children and Blue Suede Shoes: Christians and Popular Culture, will be speaking at Wallace Presbyterian Church in College Park, Maryland, on how alert imaginations enable us to receive the meaning in Creation and to rearticulate Creation’s meaning in works of art. A former arts and humanities editor for NPR, Myers writes of the mission of Mars Hill’s bimonthly “audio journal”: “We explore the various factors that have given modern Western culture its distinctive character. We also try to describe what cultural life — its practices, beliefs, and artifacts — might look like if it was the product of thoughtful Christian imaginations.” Each issue features guests from a variety of disciplines (poets, visual artists, scientists, philosophers, musicians and musicologists, social commentators, etc.); you can listen to back issues here, and read a 2013 profile on Myers from the Weekly Standard here. This event is sponsored by the Eliot Society, a new nonprofit in Washington, DC, that aims to “draw Christian faith and artistic culture back together, by promoting the thoughtful exploration of the work of creative men and women from both the past and the present.” Click here to RSVP.

+++

Last season’s Italia’s Got Talent featured a group called Quadri Plastici (“Living Paintings,” or “Tableaux”), which uses actors in period costumes and special lighting effects to recreate famous religious paintings in the flesh. According to the group’s website, the tradition of staging live reproductions of paintings originated in Avigliano in southern Italy in the 1920s: the participants, frozen in position, would be rolled into the town square on mule-drawn carts as part of the celebration of Saint Vitus’s feast day on June 15. In their television performance last year, Quadri Plastici recreated three Caravaggio paintings: The Crucifixion of Saint Peter, The Calling of Saint Matthew, and The Death of the Virgin. Gabriele Finaldi, director of London’s National Gallery, was impressed, and he commissioned the group to perform two of the paintings from the museum’s “Beyond Caravaggio” exhibition in October: The Taking of Christ and Salome Receives the Head of John the Baptist. To better engage the public, these stagings took place outside in Trafalgar Square.

+++

Through Paul Neeley’s Global Christian Worship blog, I discovered a gem of a song: a heavy-metal arrangement of the nineteenth-century Swedish hymn “Bred dina vida vingar” (Thy Holy Wings) by the Finnish worship band Metallmässa (Metal Mass). Unlike its marginal status in most countries, heavy metal music is mainstream in Finland, which has the most heavy metal bands per capita in the world. “Metal masses”—church services performed in a heavy-metal style—became a trend in 2006; into this current stepped the group Metallmässa, whose lead singer, Christer Romberg, was a contestant on the 2007 Finnish Idols. Their headbanging rendition of “Bred dina vida vingar,” performed in the music video below, is from their 2012 EP Sanctus. The words are by Lina Sandell, “the Fanny Crosby of Sweden”; the tune—which I think is just beautiful (and quite catchy!)—is a traditional Swedish folk tune. Metallmässa is no longer active, but Romberg can be found performing a cappella with his four siblings as part of Vokalgruppen Romberg.

+++

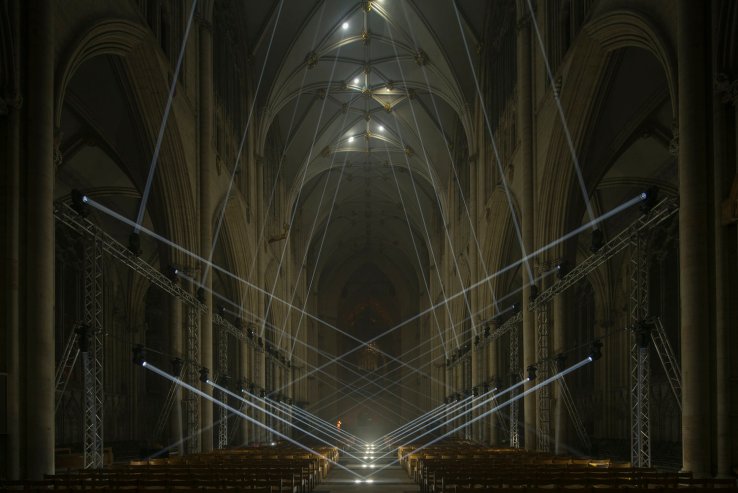

Recently I enjoyed listening online to James K.A. Smith’s lecture “A Postmodern Saint? Augustine in France,” given at Wheaton College on August 31, 2016. Because I’m interested in how culture shapes our longings (in particular, visual culture), the bit that starts at 19:57 jumped out at me:

Augustine is a remarkable exegete of cultural liturgies that beset us—the rites and rituals of ambition, consumption, privilege, that aren’t just things that we do but do things to us. The frat house, the football stadium, the rituals of Wall Street finance—these are quasi-religious sites in late modern culture, not because they purvey a message but because they are incubators of love that are rife with rituals that train and direct our hearts and our desires. And conversion is no magical panacea for that; belief doesn’t inoculate our loves from their immersion in those cultural liturgies. So we need to constantly take stock of the formation of our loves and longings, all the subtle ways that secular liturgies bend our desires toward earth rather than heaven.

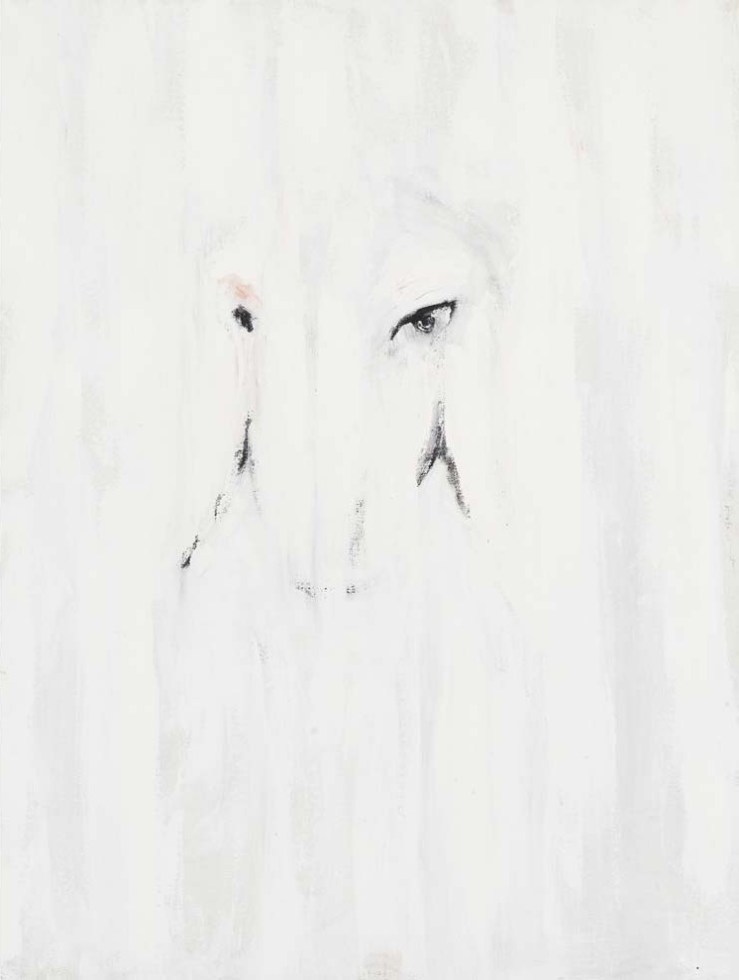

Consider, too, the act of looking as a cultural liturgy: at our phones and computer screens; at the staged displays in store windows, and the staged photos on social media; at the thirty-second commercial the network forces us to watch before we get back to our show, or the billboard we can’t help but notice when we’re stuck in traffic. Sometime around the year 600, Pope Gregory I insightfully wrote that pictures teach us what to adore, what to imitate. What pictures do you see throughout the day? Is Christ one of them?