i thank You God for most this amazing

day:for the leaping greenly spirits of trees

and a blue true dream of sky;and for everything

which is natural which is infinite which is yes

(i who have died am alive again today,

and this is the sun’s birthday;this is the birth

day of life and of love and wings:and of the gay

great happening illimitably earth)

how should tasting touching hearing seeing

breathing any—lifted from the no

of all nothing—human merely being

doubt unimaginable You?

(now the ears of my ears awake and

now the eyes of my eyes are opened)

This poem was originally published in Xaipe1 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1950), reissued in 2004 by Liveright, an imprint of W.W. Norton & Company. Reprinted here by permission of the publisher. Copyright expires 2045.

Edward Estlin Cummings (1894–1962), known as E. E. Cummings,2 is one of America’s most famous twentieth-century poets. Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, he was raised, a pastor’s son, in the Unitarian faith, which emphasizes the oneness of God. As an adult he wed this spiritual framework to Emersonian transcendentalism, a philosophical movement that celebrates humanity and nature. Elements from these two complementary traditions can be detected in his praise poem “i thank You God for most this amazing,” in which the natural world triggers an awakening to Truth. And for Cummings, Truth is a person, a “You” with a capital Y.

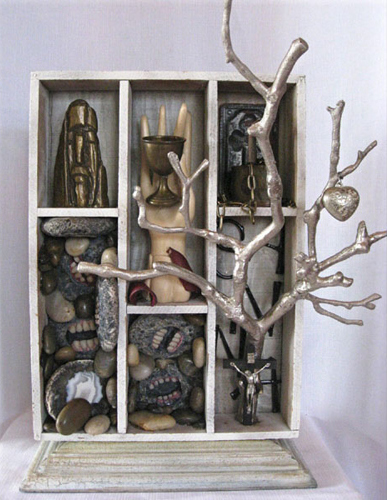

Humanities students are always introduced to Cummings as a poet, but actually, painting is the endeavor he invested most of his time in.3 One of his favorite subjects to paint was the landscape surrounding his summer home at Joy Farm in Silver Lake, New Hampshire (see image above). The elation he felt in this environment of wooded hills, fields, and lake he worked into several of his poems. I wonder if the phrases “leaping greenly spirits of trees” and “blue true dream of sky” were inspired by a view from his farmstead one August day.

Cummings is notorious for his idiosyncratic poetic style, which is marked especially by unconventional syntax—that is, a nonlogical ordering of words. This device is at play in the awkward first line of our present poem, which dislocates “most”: instead of “i thank You God for this most amazing / day” (this day is so amazing) or even “i thank You God most for this amazing / day” (this day is what I’m most thankful for), we have “i thank You God for most this amazing / day.” By inverting the word order, Cummings draws attention to the word “most,” traditionally an adverb but in this position an indeterminate part of speech. Continue reading ““i thank You God for most this amazing” by E. E. Cummings”