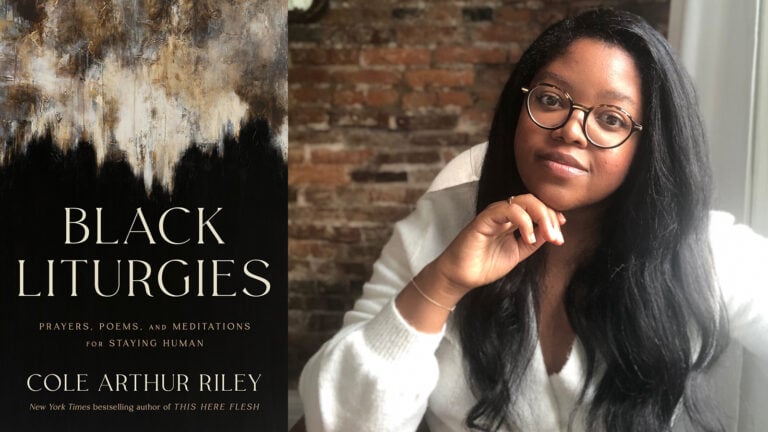

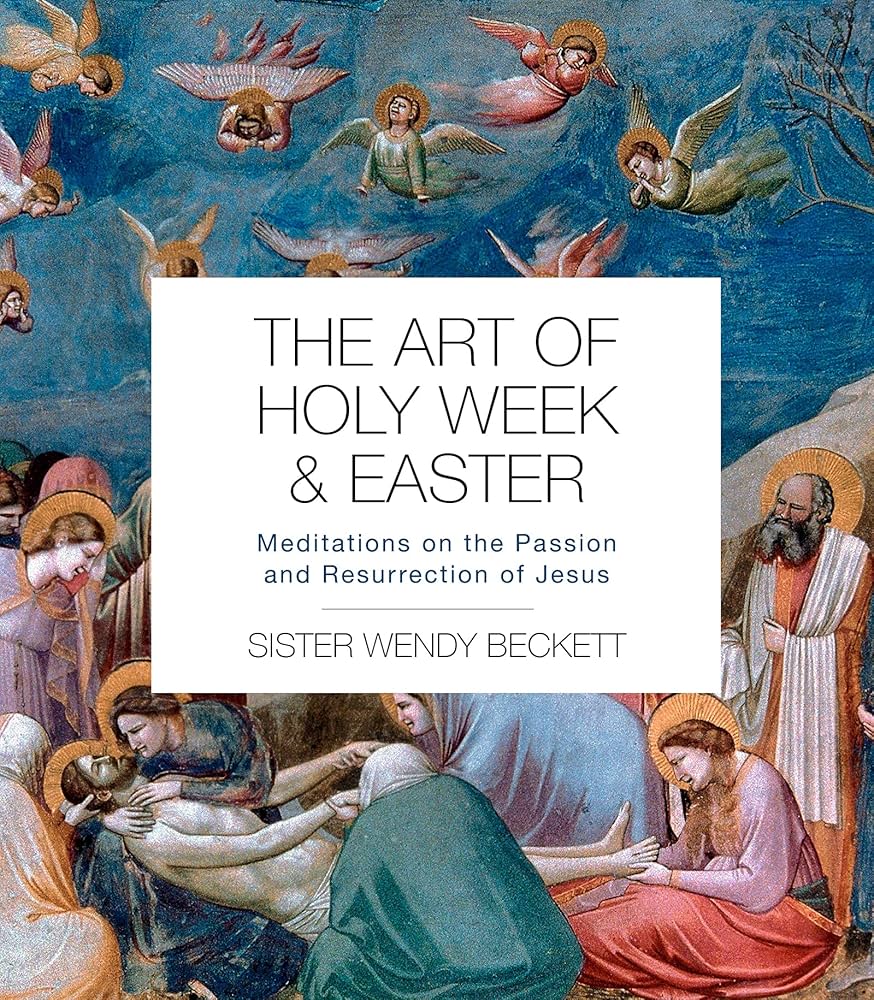

BOOK: The Art of Holy Week and Easter: Meditations on the Passion and Resurrection of Jesus by Sister Wendy Beckett (2021): Sister Wendy Beckett, a British Catholic nun and art enthusiast who died in 2018, is the one who first got me interested in art history. We watched clips from her BBC series Sister Wendy’s Story of Painting in my studio art class in high school, and I was so drawn to the way she looked at art and talked about it. Enthusiastic, warm, inquisitive, spiritually sensitive and theologically astute, and interested not just in the technical qualities of a work but also in its content—though I know I lack the same flair, my own voice and approach when it comes to art are indebted to hers.

So I was delighted to see that SPCK (and IVP in North America) has published two church calendar–based art devotionals by Sister Wendy: one for Lent, and one for Holy Week and Easter. I was disappointed with The Art of Lent: It has an admirable diversity of art selections, but Sister Wendy’s reflections are short and basic, and most don’t shine in the way I’ve come to expect from her; there were only two standouts for me. I also found it thematically confusing (for example, a section on “Confidence”?), unfocused, and redundant (especially in the “Silence” and “Contemplation” sections). I will grant that Lent is a more difficult season to structure for a project like this than Advent is, as I found the one year I published a daily Lent series; it can mean many things to many people.

Sister Wendy’s The Art of Holy Week and Easter, on the other hand, I did enjoy and recommend. I wish it had the same variety as the Lent book. (There’s only one modern/contemporary painting.) I care for only about half the featured artworks—two favorites are below—but even for the ones I was disinclined toward, her commentary helped me appreciate them.

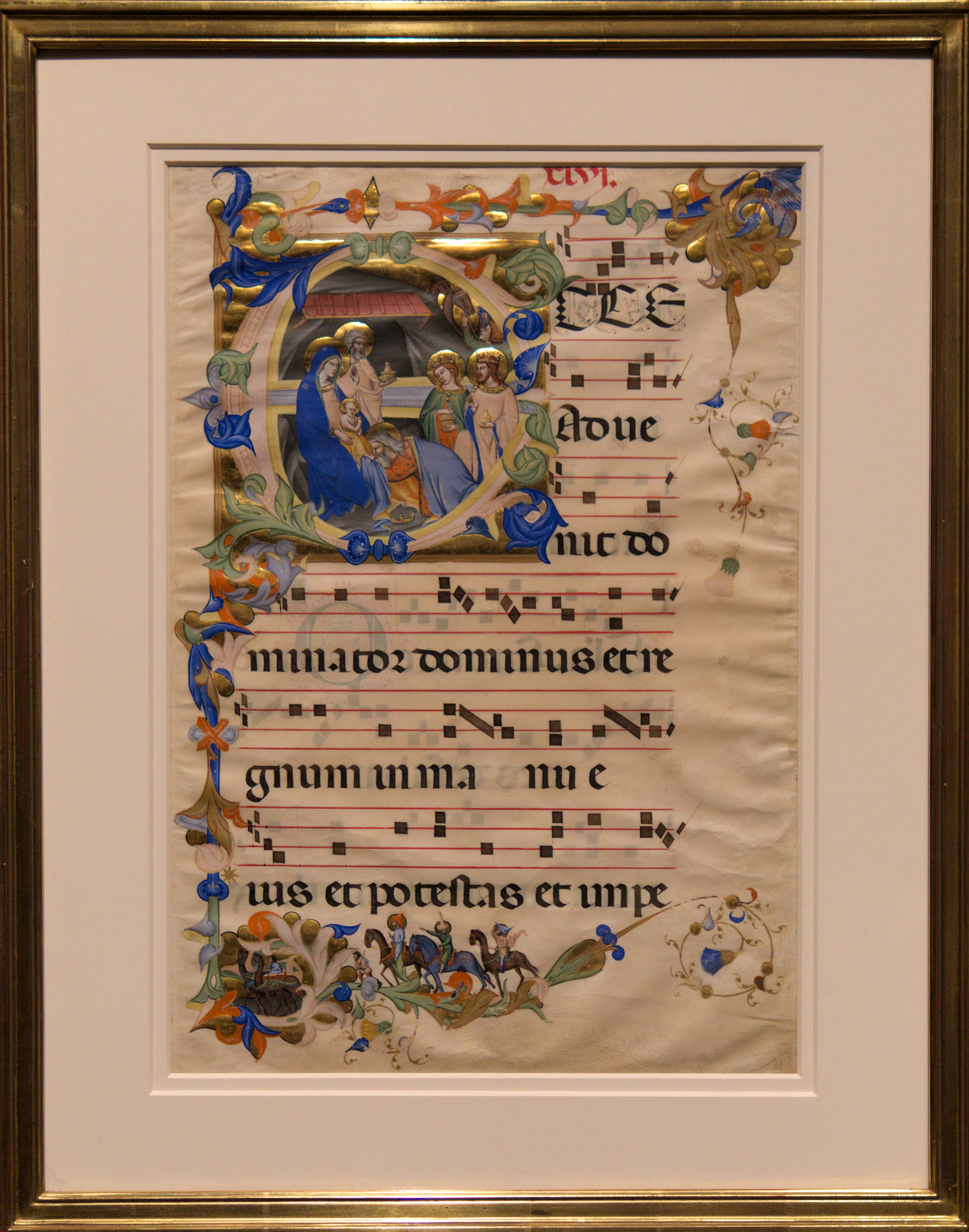

About a medieval manuscript illumination of Peter weeping by Cristoforo de Predis, Sister Wendy writes:

This magical little picture presents an unforgettable image of grief. It is that most painful kind of grief, lamenting of our own folly. Here we see Peter with his shamed face covered, stumbling blindly forward from one closed door to the next. There are ways out behind him, but Peter is too lost in misery to look for them. This claustrophobic despair, this helpless anguish, this incapacitating sense of shame: these are the result of a sudden overturn of our own self-image.

Peter had honestly seen himself as one who loved and followed Jesus, priding himself, moreover, on how true his loyalty was in comparison with that of others. ‘Even if all should betray you, I will never betray you’ – it was a boast, but he had meant it. Now he sees, piercingly, that he is fraudulent. He has been unmasked to himself, he has lost his self-worth.

The crucial question is: What next? Will he hide his face forever, destroyed by self-pity? Will he lose all heart, perhaps even kill himself, as Judas did? But while Judas felt only remorse, Peter feels contrition, a healing sorrow that will lead to repentance and a change of heart. Now that he knows his true weakness, he will cling to Jesus as never before. He will cling in desperate need and not in false strength, and will in the end become truly Peter, the ‘rock’, on which the Church, likewise dependent on Christ, will be built. (26)

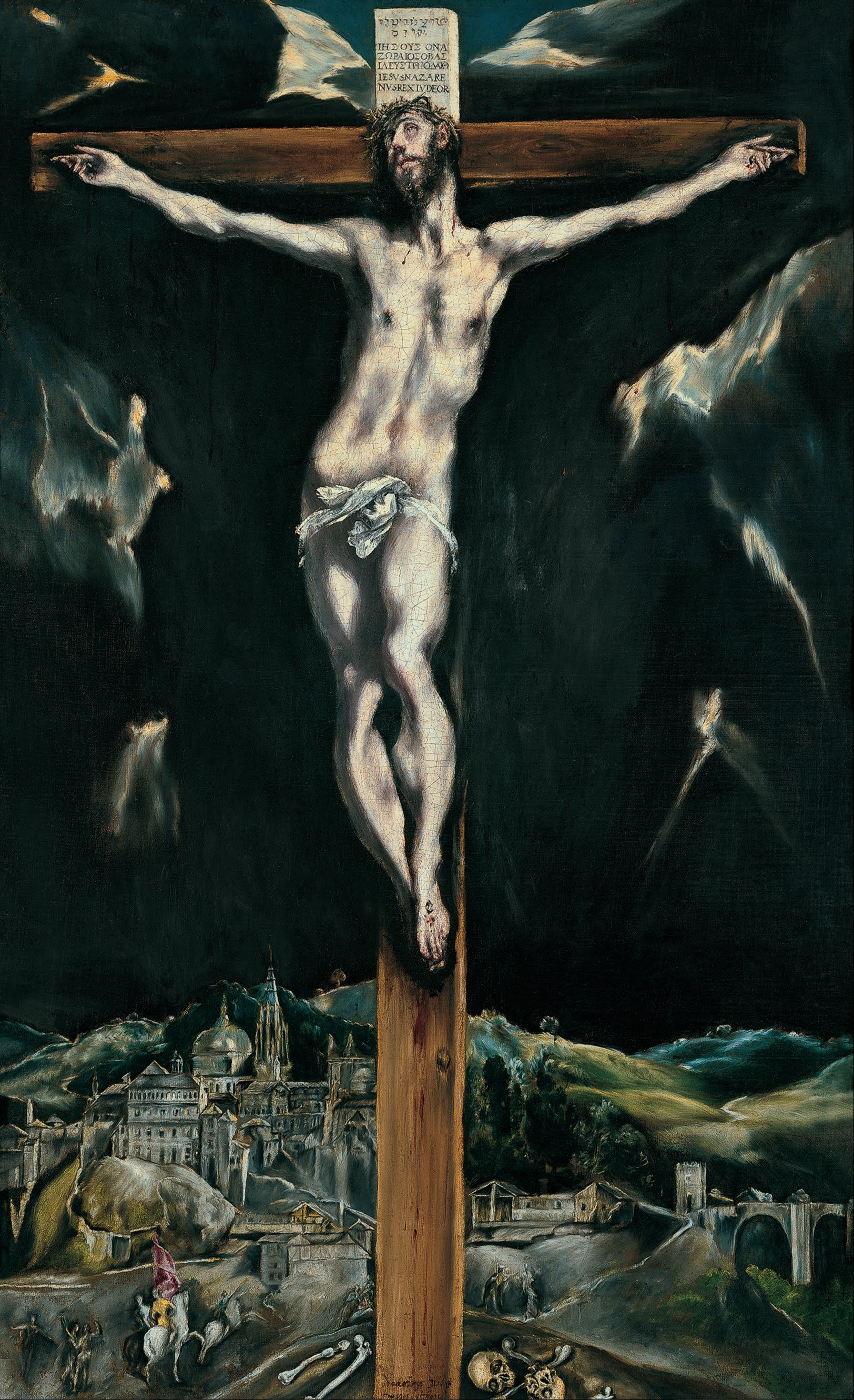

About El Greco’s Christ Crucified, she mentions how “Jesus . . . dies looking upwards, his determination set upon his Father’s will and its consummation. . . . His body spirals upwards like a white flame, radiating out as he spreads his arms to share the light with the defeated shadows” (38).

+++

HYMNS:

>> “O Love, How Deep, How Broad, How High”: I’ve enjoyed learning a few new-to-me hymns from the YouTube channel of Josh Bales. Attributed to the fifteenth-century German-Dutch Catholic mystic Thomas à Kempis, this hymn text was translated from Latin into English by Benjamin Webb in 1871. It appears in the Episcopal hymnal with the tune EISENACH by Bartholomäus Gesius, as adapted by Johann Hermann Schein in 1628, which is what Bales sings. It’s rare among hymns for emphasizing that our salvation was won not just by Christ’s death but also by his life—his faithful obedience to the Father.

>> “I Stand Amazed (How Marvelous)”: A favorite from my childhood, this 1905 gospel hymn by Charles H. Gabriel is performed here by the Imani Milele Choir, made up of orphaned and/or vulnerable children and youth from Uganda.

>> “Come Let Me Love”: I recently learned of this shape-note hymn from a book I’m reading by J. R. Watson. Written by the late great Isaac Watts, the text was first published in the 1706 edition of Watts’s Horæ lyricæ with the title “Christ’s Amazing Love and My Amazing Coldness.” I especially love verses 4 and 5, reproduced below. The tune in the following video, LAVY, is actually a new one (from 1993) that sounds old, by John Bayer Jr.

Infinite grace! Almighty charms!

Stand in amaze, ye rolling skies!

Jesus, the God with naked arms,

Hangs on a cross of love and dies.Did pity ever stoop so low,

Dress’d in divinity and blood?

Was ever rebel courted so,

In groans of an expiring God?

+++

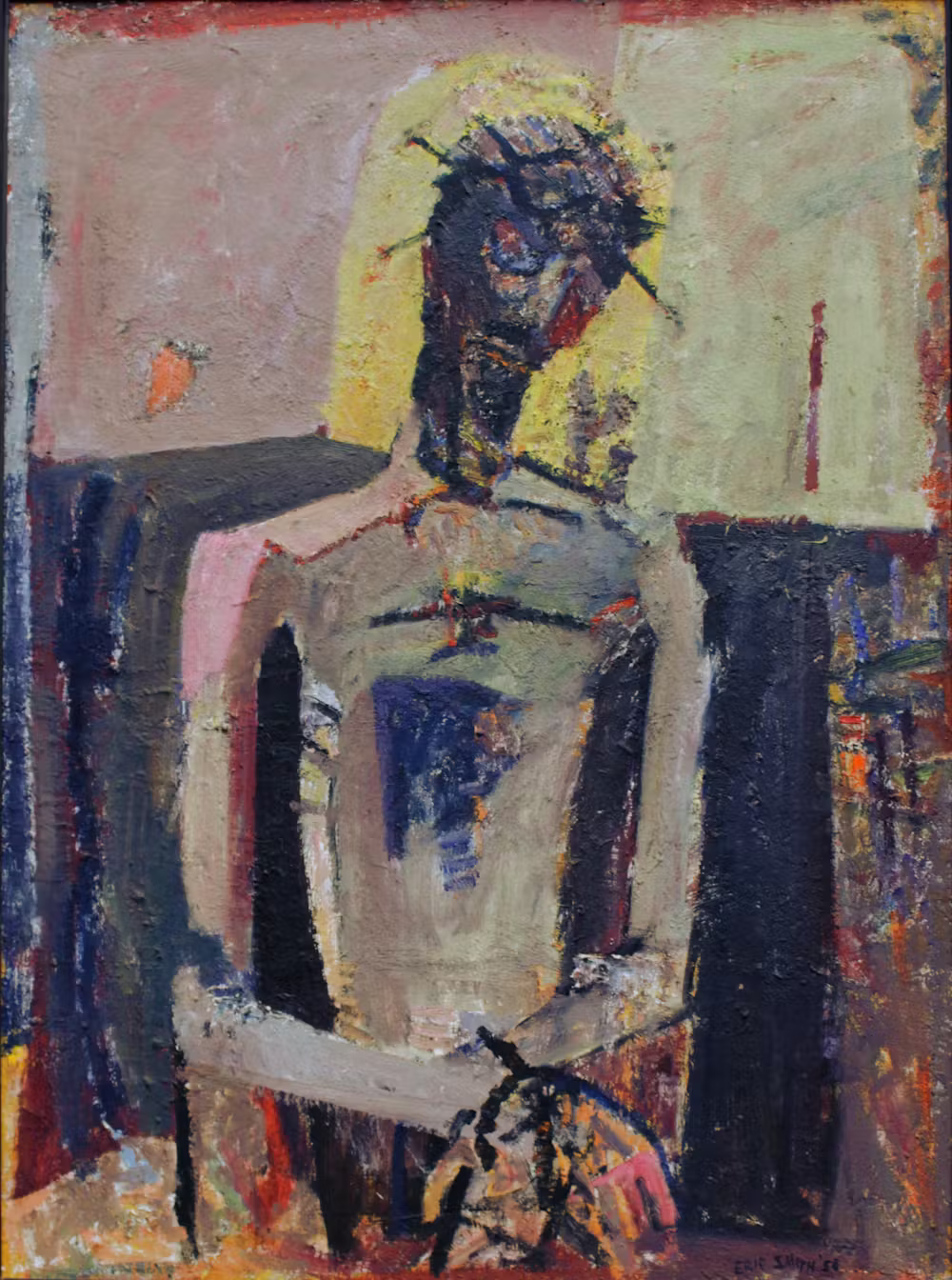

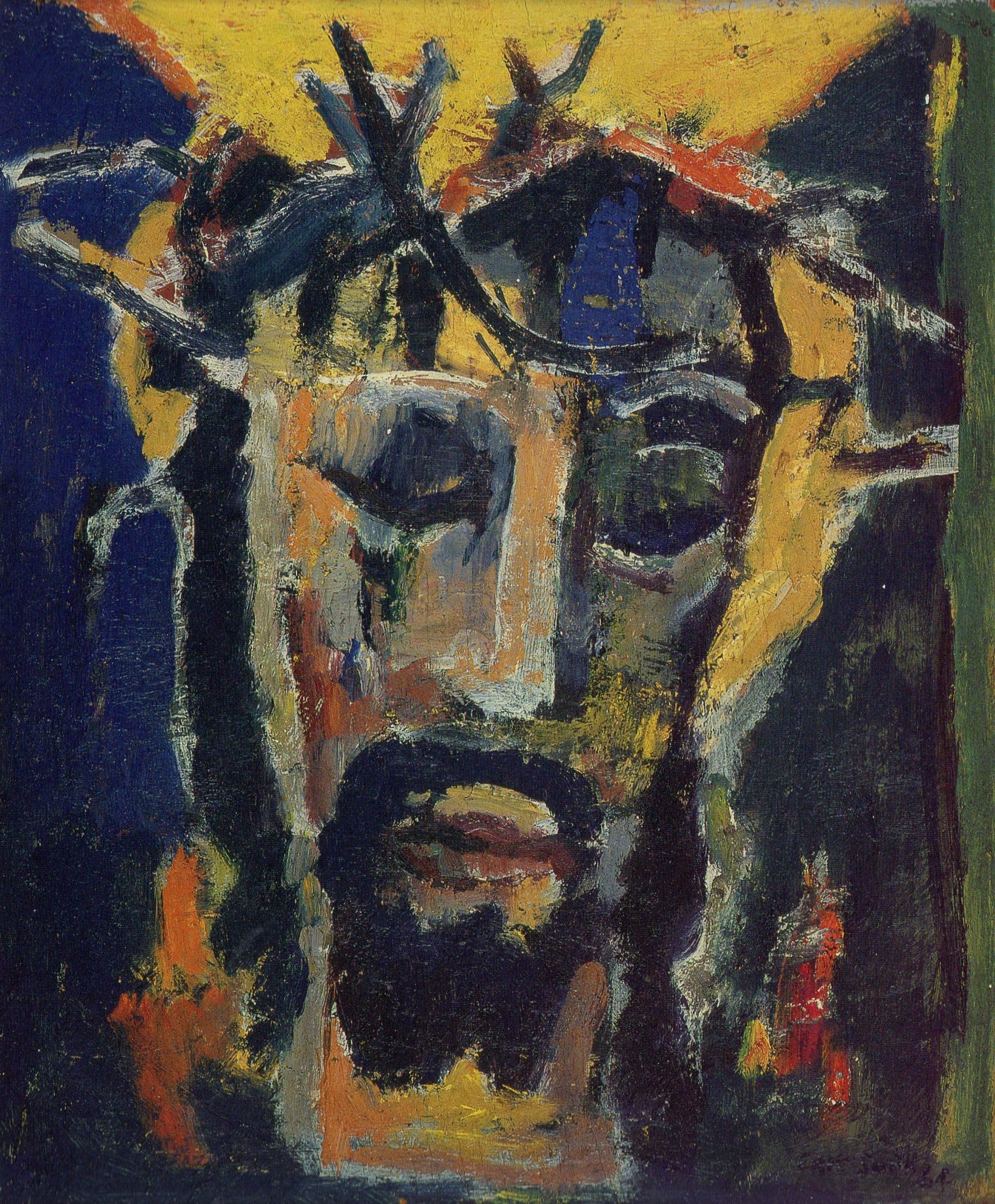

VIDEO: “Christ by Eric Smith”: This is the first video in the (Catholic) Archdiocese of Brisbane’s four-part Art Aficionados series from 2022. In it, Archbishop Emeritus Mark Coleridge, theology professor Maeve Heaney, and Rev. Dr. Tom Elich of Liturgy Brisbane discuss the semiabstract Ecce homo painting Christ by the modern Australian artist Eric Smith—its pathos, calm, and double irony. This Christ is crushed yet composed, Coleridge says. Smith won the prestigious Blake Prize for Religious Art six times, including, in 1956, for a painting similar to this one (see second image in slideshow below). I’d love to see more dioceses releasing videos like this!—close looking at art.

The other videos in the Art Aficionados series are on The Stories That Weren’t Told by Lee Paje, The Good Samaritan by Olga Bakhtina, and The Visitation by Jacob Epstein.

+++

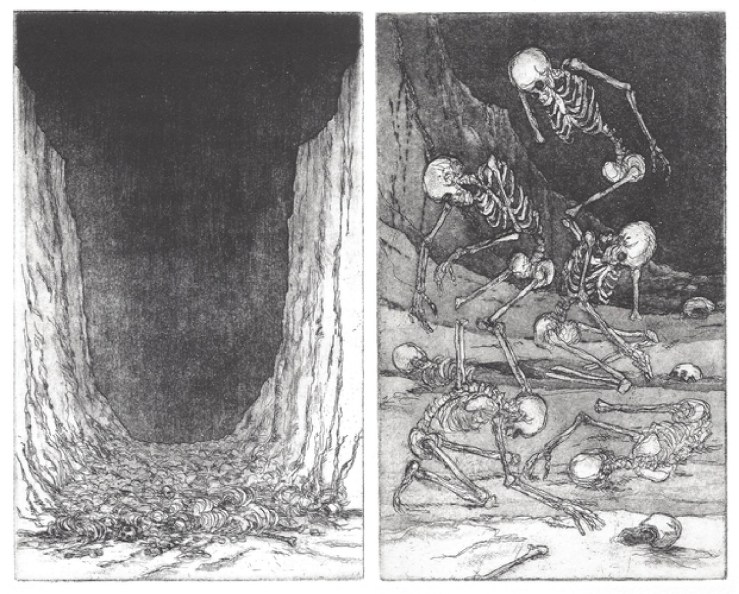

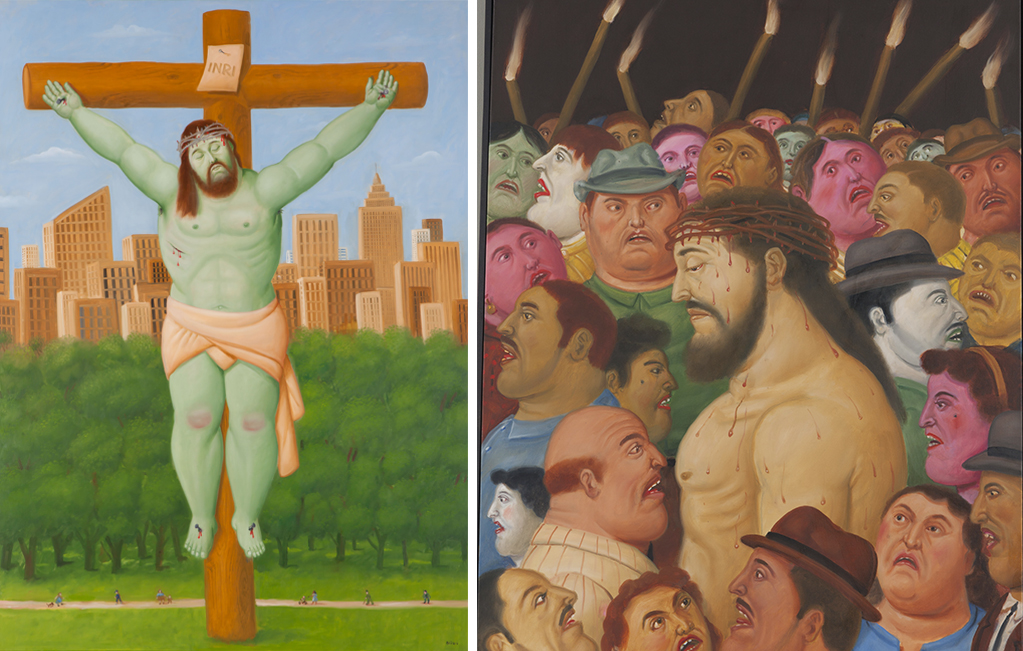

ART SERIES: Via Crucis: La pasión de Cristo (Way of the Cross: The Passion of Christ) by Fernando Botero: Executed in 2010–11, Via Crucis is a series of twenty-seven oil paintings and thirty-four mixed-media drawings by Colombia’s most famous artist, Fernando Botero (1932–2023) [previously]. Botero said he turned to the subject of Christ’s passion not because he’s religious, but out of admiration for the great works of art on the subject; he approached it with “a spirit of great respect,” aiming to portray God as a tortured man. The artist donated the series to the Museo de Antioquia in Medellín for his eightieth birthday. I can’t find a compilation of the whole series (the museum has digital records of the Boteros in its collection, but not all the images are showing up for me)—but you can view fourteen of the paintings in this article, and here’s a quick little Facebook reel.

Marlborough Gallery in New York offers a catalog of the series for $75, and Artika offers a much more expensive one (a gorgeous product, but $9,500!):

Here’s a news segment, in English, about the series’ exhibition at Lisbon’s Palacio de Ajuda in November 2012 (unfortunately, the video quality is low):

+++

I have thematic playlists on Spotify for Lent and Holy Week—for the latter, don’t miss “From the Garden to the Tomb” by The Soil and The Seed Project, one of several recent additions.

But, by popular request, I also have a brand-new March 2026 playlist, a somewhat random assortment of songs I’ve been enjoying—some new releases, some not.