PRAYER: “A Liturgy for the Wrapping of Christmas Gifts” by Wayne Garvey and Douglas McKelvey: Taken from Every Moment Holy, volume 3 from the Rabbit Room Press.

+++

ART SERIES: Magnificat by Mandy Cano Villalobos: Mandy Cano Villalobos [previously] is a multidisciplinary artist from Grand Rapids, Michigan. Her Magnificat series consists of bundles of discarded clothing, bound in string and meticulously hand-coated with imitation gold. The title—the Latin name of Mary’s praise song that opens, “My soul magnifies the Lord!”—invites associations with the Christmas story, including the image of the swaddled Christ child, a gift to the world that surprises and delights.

The series debuted in 2019 at Cano Villalobos’s solo show All That Glitters at the Urban Institute for Contemporary Arts (UICA) in Grand Rapids. I first encountered it, though, through online promotions of Sojourn Midtown’s Advent 2020 installation to correspond with the church’s sermon series Wrapped in Flesh, for which twelve of the artist’s works, some from her related Cor Aurum (Heart of Gold) series, were placed in niches around the sanctuary.

“The objects, all made of wood and fabric covered in imitation gold, point to something both humble and glorious,” writes Michael Winters, Sojourn Midtown’s arts and culture director. “Like these small sculptures of rags and gold, the birth of Jesus was also marked by humility and glory.”

+++

ARTICLE: “My Swaddled Savior” by Jeff Peabody, Christianity Today: Pastor Jeff Peabody of Tacoma, Washington, describes the traditional Japanese art of furishoki, or wrapping goods in cloths, as he reflects on Jesus having been swaddled as an infant, a wrapped gift given to the world. “Jesus came to us in furoshiki, wrapped in cloths,” he writes.

+++

BLOG POST: How to receive gifts and enjoy feasting without shame, by Tamara Hill Murphy: In this old blog post of hers, spiritual director and The Spacious Path author Tamara Hill Murphy absolves us of the guilt we so often feel around (1) receiving (unreciprocated) gifts and (2) feasting. We should receive both presents and food, she says, as means of grace. Too often we’re embarrassed when we receive a gift from someone to whom we gave no gift, or a gift of lesser value, and so instead of receiving their gift with joy, we receive it with shame or an annoying sense of obligation. But Murphy says she hopes to receive gifts this way: “When Jesus told us to come to him as little children, he must have been imagining the way children openly, delightedly, innocently receive gifts. Children do not question their place as ones worthy of receiving gifts. Children boldly believe the beauty of unearned kindness.”

As for food, how many times have you been to a Christmas party or dinner and heard people bemoan all the fat and sugar they’ve been consuming, and about how they’ll have to punish their body in the new year to work off the extra calories, to shrink themselves back down to size? Feasting, though, is a spiritual discipline, a way to celebrate important events, like the birth of Christ, with family and friends. Feel no shame about indulging in gustatory pleasures this Christmas! Take in the sweet, the creamy, and the juicy! Murphy’s mom’s motto for hospitality is a wise one: “While we feast, we savor.”

On her blog A Clerk of Oxford, medievalist Eleanor Parker also affirms the virtue of feasting, noting how the popular modern practice of fasting in January runs counter to medieval Christian practice:

Since the late 20th century it’s become common to invert the traditional relationship between fasting and feasting in the Christmas season. The ancient custom was to fast in Advent in preparation for the feast, and then to celebrate for at least twelve days after Christmas (and to some degree, all through January). Now we do it the other way around; for many people the feast is followed by a penitential fast, in the form of ‘Dry January’ or New Year’s resolutions about eating less and going to the gym. As a manifestation of the desire for a fresh start, this ‘new year, new you’ impulse is natural enough, but it does strike me as strange that it’s so often framed in negative terms. There’s an odd sense, encouraged mostly perhaps by journalists and advertisers, that the indulgence of Christmas is a ‘sin’ which has to be atoned for – as if eating and drinking with friends and family, to celebrate the turn of the year from darkness to light, is a moral lapse for which one must subsequently make amends by privation and self-punishment. We are much less kind to ourselves in these weeks after Christmas than the strictest confessor would have been in the Middle Ages. Feasting at Christmas is not something to atone for, but a proper observance due to the season; and that feasting is also the sustenance we need to carry us into the New Year with energy and strength.

+++

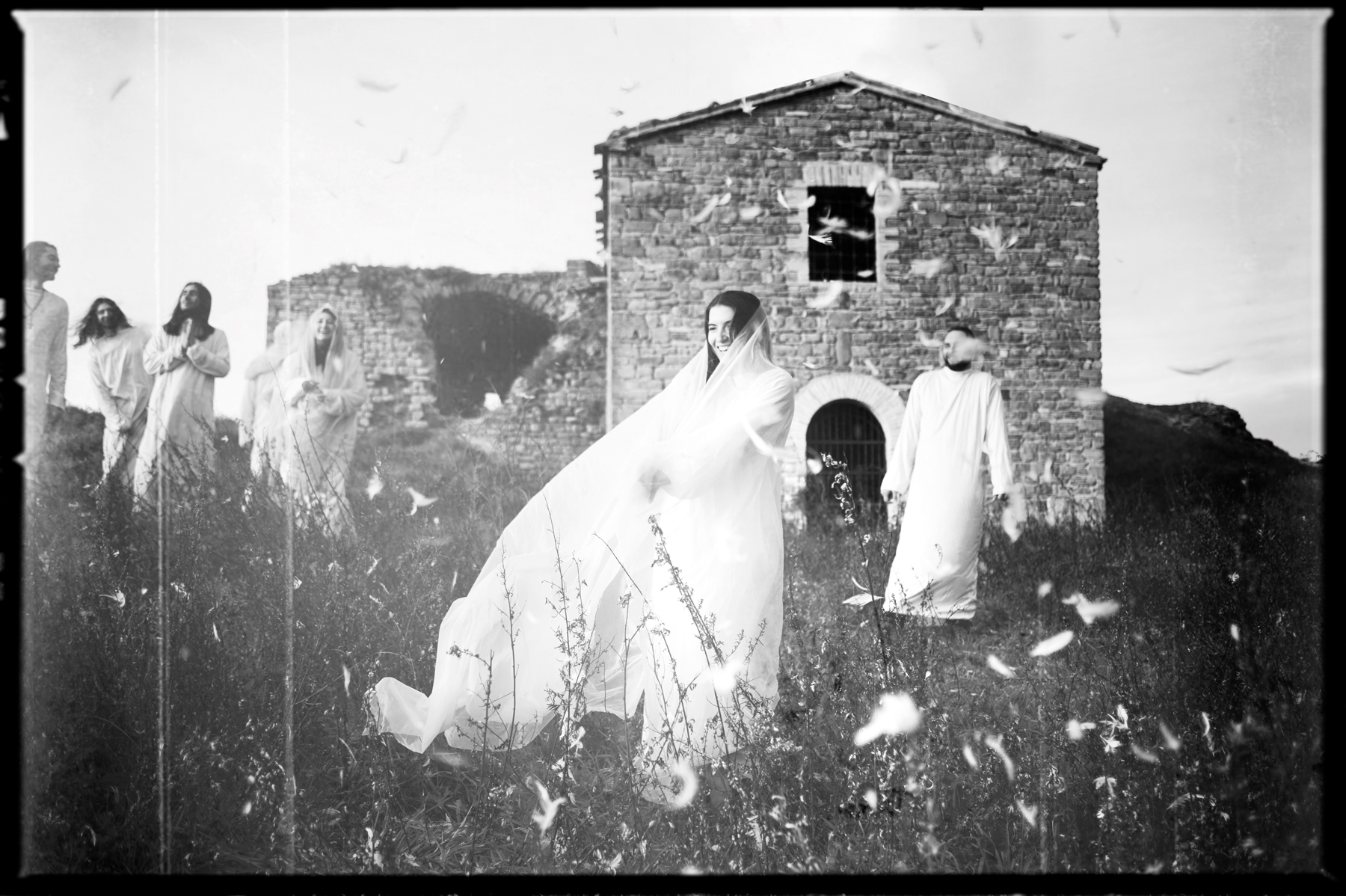

VIDEO: “Our Vocation of Delight: On Advent, Beauty, and Joy” by Christen Yates: In this thirty-minute “Space for God” Advent devotional from Coracle, artist Christen Yates (Instagram @christenbyates) invites us to experience the Christian “duty of delight” through engaging a selection of artworks by herself, Sedrick Huckaby, Letitia Huckaby, and Ashley Sauder Miller. She opens with a liturgical commission she fulfilled for the Advent season while serving as artist in residence at her church in Charlottesville: a portrait painting of congregation member Arley Bell (née Arrington), a baker who is now the owner of Arley Cakes in Richmond. Waiting for her dough to rise, Arley captures the joyful expectancy of Advent.