LOOK: Jesus as Bridegroom of the Soul from the Rothschild Canticles

The Rothschild Canticles from early fourteenth-century Flanders or the Rhineland (whose innovative Trinity miniatures I wrote about in 2021) is a cento of biblical, liturgical, and patristic citations accompanying an extraordinary program of images. Much of the content reflects the bridal mysticism that was popular at the time, emphasizing spiritual oneness with Christ. The compiler, artist(s), scribe(s), and original recipient of the manuscript are not known, but it was very likely made by a male monastic for a nun or canoness to use in her private devotions.

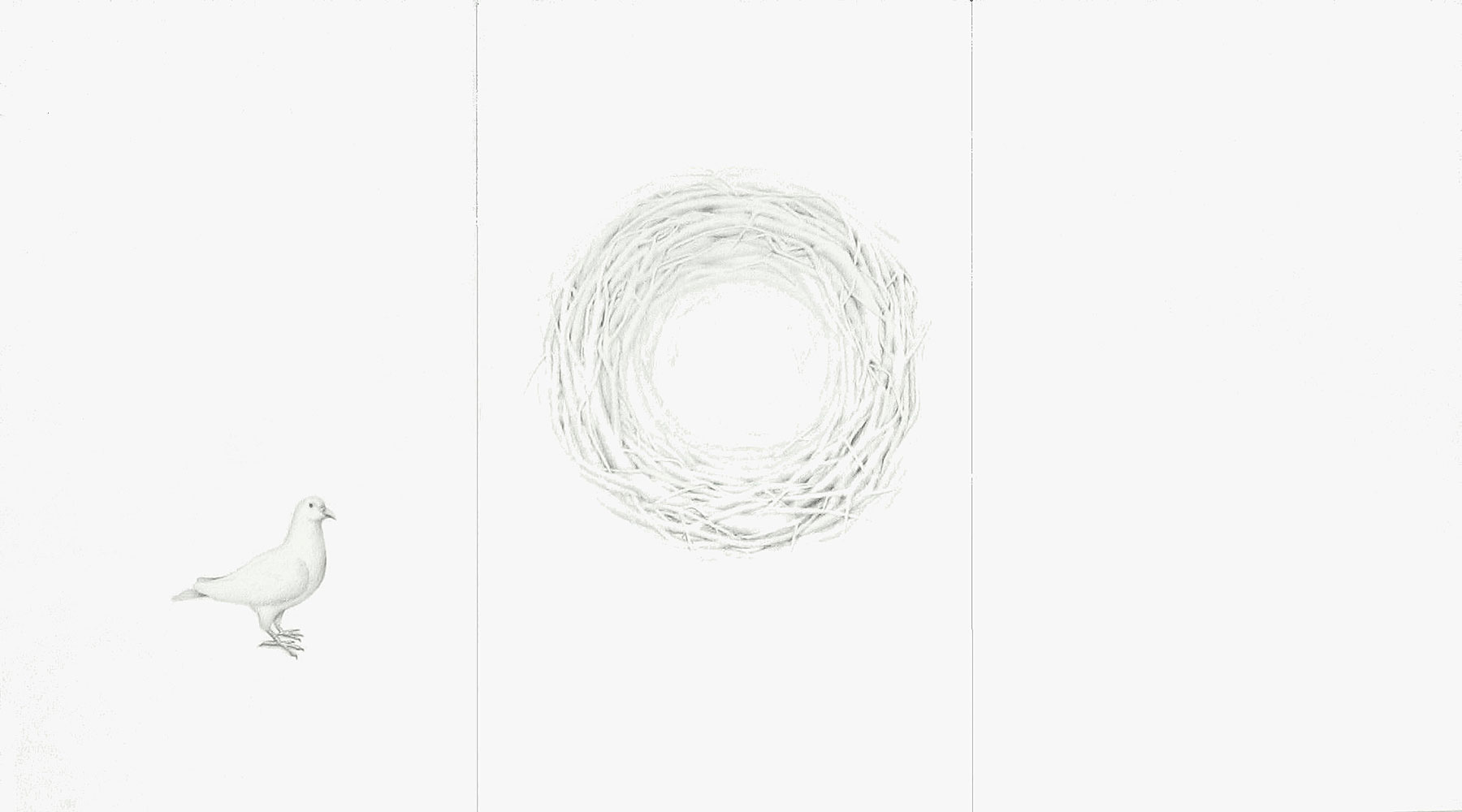

The miniature on folio 66r is the first in a five-miniature sequence (of which four survive) on the theme of mystical union. It shows the human soul, represented as a woman, about to receive her Bridegroom, Christ, in the marriage bed. Art historian Jeffrey Hamburger writes that in this image, “Christ emerges from the heavens with the energy of a cosmic explosion[,] . . . as a dramatic sunburst dissolving the mists. . . . Christ is the sun, its brightness, the light of the visio Dei. Just as sunlight generates heat, so Christ provokes desire.” [1] The artist uses that whirling sun with its tentacle-like rays as an attribute of Christ throughout the manuscript.

At her lover’s luminous descent, the Bride awakes from her sleep and raises her arms in ecstasy.

The face peeking out from behind the crescent moon on the right may be an angel, whose gaze directs us forward to the next scene, which shows the Bride reclining outdoors amid sprouting vines, “languish[ing] with love” (Song 2:5), and then being led into a wine cellar by the Bridegroom, to be inebriated by his sweet goodness (Song 2:4) .

The corresponding text on the facing page of this image, set inside a bedchamber, incorporates the following excerpts:

- “I call you into my soul, which you are preparing for your reception, through the longing which you have inspired in it.”—Augustine, Confessions X.1

- “God comes from Lebanon, the Holy One from the shady and thickly covered mountain.”—Habakkuk 3:3, used in medieval Advent liturgies

- “I passed by you again and looked on you; you were at the age for love.”—Ezekiel 16:8

- Plus miscellaneous adaptations of lines from the Song of Songs

In the Middle Ages it was common for Christian mystics, such as Mechthild of Magdeburg and Gertrude of Helfta, to describe and picture spiritual union in terms of physical union, as they “realized that bodily language better conveys the power, intensity, and personality of desire than overly spiritualized language does,” writes medievalist Grace Hamman. [2] And not only was the church, a corporate body, perceived as the bride of Christ, but so was the individual soul. The consummation of the marriage between Christ and his beloved was seen as eschatological, yes—coming at the end of time—but such intimate closeness and pleasure was also seen as something that could be enjoyed now on some level, as devotees commune with Christ through prayer, scripture reading, and the celebration of the Eucharist.

For the nun who used this book, it must have aided her in cultivating a deep love for Christ and strengthened her longing for that full and final coming together, when Christ will return to be with his bride.

To browse the other images in this remarkable manuscript, visit https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2002755.

Notes:

- Jeffrey F. Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles: Art and Mysticism in Flanders and the Rhineland circa 1300 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 106.

- Grace Hamman, Jesus through Medieval Eyes: Beholding Christ with the Artists, Mystics, and Theologians of the Middle Ages (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Reflective, 2023), 49. “The topos of the mystical marriage as an act of physical communion is commonplace. . . . Physical love is used as a metaphor for the consummation of spiritual love.” Hamburger, Rothschild Canticles, 109.

LISTEN: Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140 by Johann Sebastian Bach, 1731 | Words by Philipp Nicolai, 1599 (movements 1, 4, 7), and an anonymous other | Melody of movements 1, 4, and 7 by Philipp Nicolai, 1599

Here are two listening options—the first from an album, and the second a live performance that you can hear as well as watch.

>> Performed by the Monteverdi Choir and the English Baroque Soloists, dir. John Eliot Gardiner, on Bach: Cantatas BWV 140 and 147 (1992)

>> Performed by the Choir and Orchestra of the J. S. Bach Foundation, dir. Rudolf Lutz (soloists: Nuria Rial, Bernhard Berchtold, Markus Volpert), Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche Trogen, Switzerland, 2008 (**The copyright owner has disallowed video embeds, but you can watch the video directly on YouTube by clicking the link below.)

In the libretto that follows, the capital letters in parentheses indicate which voice parts are singing that movement: soprano, alto, tenor, or bass.

1. Choral (SATB)

Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme,

der Wächter sehr hoch auf der Zinne,

wach auf, du Stadt Jerusalem.

Mitternacht heißt diese Stunde,

sie rufen uns mit hellem Munde,

wo seid ihr klugen Jungfrauen?

Wohlauf, der Bräut’gam kömmt,

steht auf, die Lampen nehmt,

Alleluia!

Macht euch bereit

zu der Hochzeit,

ihr müsset ihm entgegen gehn.

2. Rezitativ (T)

Er kommt, er kommt,

der Bräut’gam kommt,

ihr Töchter Zions, kommt heraus,

Sein Ausgang eilet aus der Höhe

in euer Mutter Haus.

Der Bräut’gam kommt, der einen Rehe

und jungen Hirschen gleich

auf denen Hügeln springt

und euch das Mahl der Hochzeit bringt.

Wacht auf, ermuntert euch,

den Bräut’gam zu empfangen;

dort, sehet, kommt er hergegangen.

3. Duett (SB) (Dialog - Seele, Jesus)

Wenn kömmst du, mein Heil?

– Ich komme, dein Teil. –

Ich warte mit brennenden Öle.

Eröffne den Saal

– Ich öffne den Saal –

zum himmlischen Mahl.

Komm, Jesu.

– Ich komme, komm, liebliche Seele. –

4. Choral (T)

Zion hört die Wächter singen,

das Herz tut ihr vor Freuden springen,

sie wachet und steht eilend auf.

Ihr Freund kommt von Himmel prächtig,

von Gnaden stark, von Wahrheit mächtig,

ihr Licht wird hell, ihr Stern geht auf.

Nun komm, du werte Kron’,

Herr Jesu, Gottes Sohn,

Hosianna!

Wir folgen all

zum Freudensaal

und halten mit das Abendmahl.

5. Rezitativ (B)

So geh herein zu mir,

du mir erwählte Braut!

Ich habe mich mit dir

von Ewigkeit vertraut.

Dich will ich auf mein Herz,

auf meinen Arm gleich wie ein Sigel setzen,

und dein betrübtes Aug’ ergötzen.

Vergiß, o Seele, nun

die Angst, den Schmerz,

den du erdulden müssen;

auf meiner Linken sollst du ruhn,

und meine Rechte soll dich küssen.

6. Duett (SB) (Dialog - Seele, Jesus)

Mein Freund ist mein,

– und ich bin dein, –

die Liebe soll nichts scheiden.

Ich will mit dir

– du sollst mit mir –

im Himmels Rosen weiden,

da Freude die Fülle, da Wonne wird sein.

7. Choral (SATB)

Gloria sei dir gesungen,

mit Menschen- und englischen Zungen,

mit Harfen und mit Zimbeln schon.

Von zwölf Perlen sind die Pforten,

an deiner Stadt sind wir Konsorten

der Engel hoch um deine Thron.

Kein Aug’ hat je gespürt,

kein Ohr hat je gehört

solche Freude,

des sind wir froh,

io, io,

ewig in dulci jubilo.

1. Chorus (SATB)

Awake, calls the voice to us

of the watchmen high up in the tower;

awake, you city of Jerusalem.

Midnight the hour is named;

they call to us with bright voices;

where are you, wise virgins?

Indeed, the Bridegroom comes;

rise up and take your lamps,

Alleluia!

Make yourselves ready

for the wedding,

you must go to meet him.

2. Recitative (T)

He comes, he comes,

the Bridegroom comes!

O daughters of Zion, come out;

his course runs from the heights

into your mother’s house.

The Bridegroom comes, who like a roe

and young stag

leaps upon the hills;

to you he brings the wedding feast.

Rise up, take heart,

to embrace the Bridegroom;

there, look, he comes this way.

3. Duet (SB) (Dialogue - Soul, Jesus)

When will you come, my Savior?

– I come, as your portion. –

I wait with burning oil.

Now open the hall

– I open the hall –

for the heavenly meal.

Come, Jesus!

– I come, come, beloved soul! –

4. Chorale (T)

Zion hears the watchmen sing,

her heart leaps for joy within her,

she wakens and hastily arises.

Her glorious beloved comes from heaven,

strong in mercy, powerful in truth;

her light becomes bright, her star rises.

Now come, precious crown,

Lord Jesus, the Son of God!

Hosanna!

We all follow

to the hall of joy

and hold the evening meal together.

5. Recitative (B)

So come in to me,

you my chosen bride!

I have to you

eternally betrothed myself.

I will set you upon my heart,

upon my arm as a seal,

and delight your troubled eye.

Forget, O soul, now

the fear, the pain

which you have had to suffer;

upon my left hand you shall rest,

and my right hand shall kiss you.

6. Duet (SB) (Dialogue - Soul, Jesus)

My friend is mine,

– and I am yours, –

love will never part us.

I will with you

– you will with me –

graze among heaven’s roses,

where complete pleasure and delight will be.

7. Chorale (SATB)

Let Gloria be sung to you

with mortal and angelic tongues,

with harps and even with cymbals.

Of twelve pearls the portals are made;

in your city we are companions

of the angels high around your throne.

No eye has ever perceived,

no ear has ever heard

such joy

as our happiness,

io, io,

eternally in dulci jubilo! [in sweet rejoicing]

English translation © Pamela Dellal, courtesy of Emmanuel Music Inc. Used with permission.

Bach wrote this cantata during his time as cantor (music director) at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, Germany, a post he served from 1723 until his death in 1750. (Imagine having Bach write and lead music for your church. During his first few years at St. Thomas, he composed a new cantata nearly every week for Sunday worship! His productivity is uncanny.) It premiered the twenty-seventh Sunday after Trinity Sunday, the final week of the liturgical year, on November 25, 1731, to correspond to the day’s assigned Gospel reading.

Bach scored the work for three vocal soloists—soprano (playing the Soul), tenor (the Watchman), and bass (Jesus)—a four-part choir, and an instrumental ensemble consisting of a horn, two oboes, taille, violino piccolo, strings, and basso continuo, including bassoon. Musicologist William G. Whittaker calls it “a cantata without weaknesses, without a dull bar; technically, emotionally and spiritually of the highest order. Its sheer perfection and its boundless imagination rouse one’s wonder time and time again.”

Conductor Rudolf Lutz of the J. S. Bach Foundation gave an excellent lecture with theologian Karl Graf prior to the above performance, which is freely available online; together the two break down the cantata’s musical and theological elements. The lecture is in German with English subtitles.

The first time I ever heard Bach’s Cantata 140 was in the Western music history course I took my first year of college. Our professor played a recording of the opening movement in class, then told us to go home and listen to the other six for homework—we would discuss them the next day. Sitting before my laptop at my dorm room desk, ensconced in my headphones, I was transported.

Bach’s Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme (Awake, calls the voice to us) is based on a chorale (congregational hymn) of the same name by the German Lutheran pastor, poet, and composer Philipp Nicolai, which conflates the parable of the ten virgins in Matthew 25 with the bridal theology of the Prophets and Revelation. The hymn appears in some English-language hymnals under the title “Wake, Awake, for Night Is Flying” (Catherine Winkworth) or “Sleepers, Wake! A Voice Astounds Us” (Carl P. Daw). Bach used the hymn’s three stanzas, both text and tune, for movements 1, 4, and 7.

The words of movements 2, 3, 5, and 6 are possibly by Picander (the pseudonym of Christian Friedrich Henrici), a frequent literary collaborator of Bach’s. Tender and rapturous, they draw on the imagery of the Song of Songs to describe the marriage of Christ and the human soul.

It’s a remarkable work. I encourage you to listen to it in one sitting—it’s twenty-eight minutes long—while you follow along with the lyrics. Revel in the love of Christ for you, his bride. Get excited for the sweet union to come.

As a bonus, here’s a gorgeous performance of the Nicolai hymn that forms the core of Bach’s cantata. It was arranged by F. Melius Christiansen in 1925 and performed in 2018 by the St. Olaf Massed Choirs under the direction of Anton Armstrong, using William Cook’s 1871 English translation:

Wake, awake, for night is flying,

the watchmen on the heights are crying.

Awake, Jerusalem, arise!

Midnight’s solemn hour is tolling,

his chariot wheels are nearer rolling;

he comes; prepare, ye virgins wise.

Rise up, with willing feet,

go forth, the Bridegroom meet. Hallelujah!

Bear through the night

your well-trimmed light,

speed forth to join the marriage rite.Hear thy praise, O Lord, ascending

from tongues of men and angels blending

with harps and lute and psaltery.

By thy pearly gates in wonder

we stand, and swell the voice of thunder

in bursts of choral melody. Hallelujah!

No vision ever brought,

no ear hath ever caught,

such bliss and joy.

We raise the song, we swell the throng,

to praise thee ages all along.