Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God . . .

It has a great, high wall with twelve gates, and at the gates twelve angels, . . . and the twelve gates are twelve pearls. . . .

I saw no temple in the city, for its temple is the Lord God the Almighty and the Lamb. And the city has no need of sun or moon to shine on it, for the glory of God is its light, and its lamp is the Lamb. The nations will walk by its light, and the kings of the earth will bring their glory into it. Its gates will never be shut by day—and there will be no night there. . . .

Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life, bright as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb through the middle of the street of the city. On either side of the river is the tree of life with its twelve kinds of fruit, producing its fruit each month, and the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations. Nothing accursed will be found there any more. But the throne of God and of the Lamb will be in it, and his servants will worship him; they will see his face, and his name will be on their foreheads. And there will be no more night; they need no light of lamp or sun, for the Lord God will be their light, and they will reign forever and ever.

—Revelation 21:1–2, 12, 21–25; 22:1–5

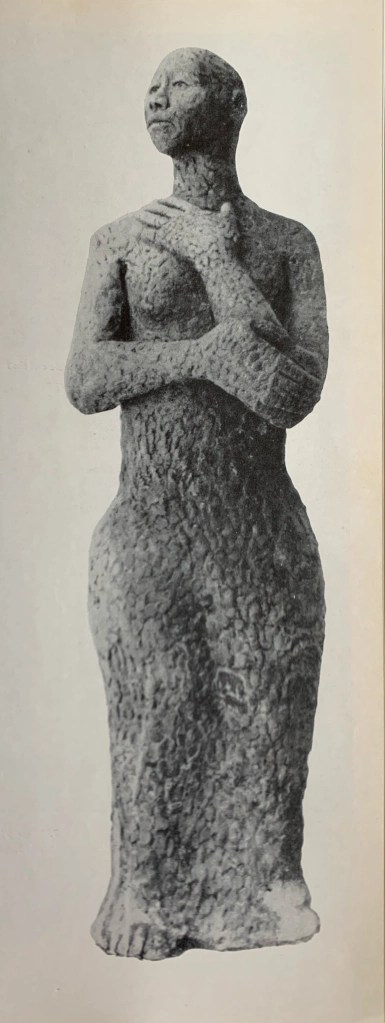

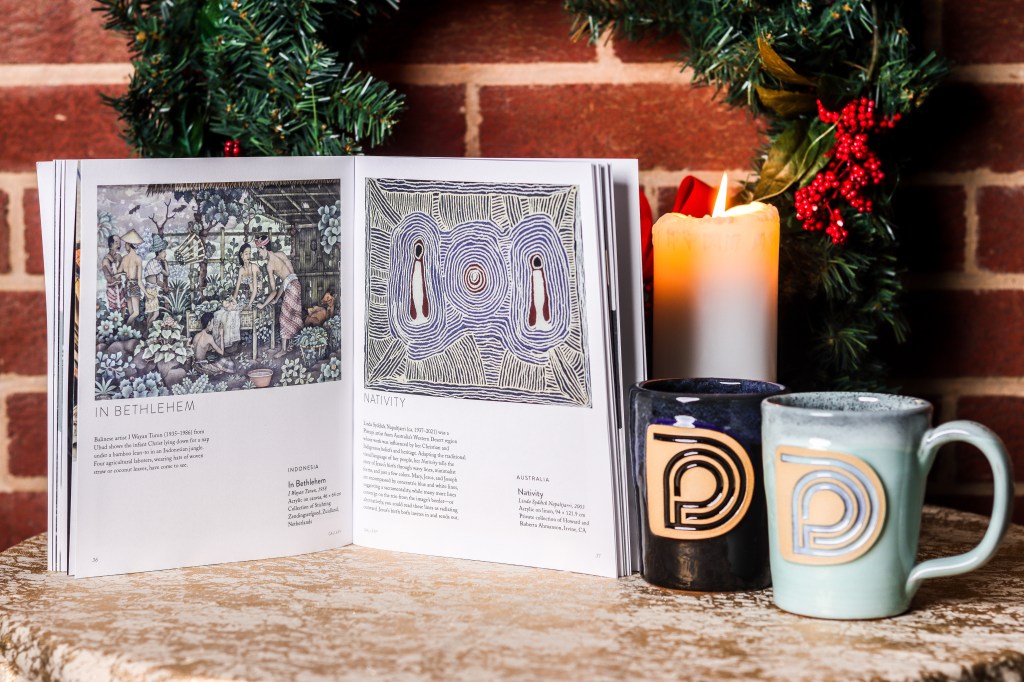

LOOK: The New Heaven by Leroy Almon

This mixed-media depiction of heaven by African American folk artist Leroy Almon draws on imagery from the book of Revelation, showing centrally a crystal-bright river, the water of life, flowing forth from the mouth of God (Rev. 22:1–2). It courses through the paradisal scene, past the tree with its twelve fruits and healing leaves, and is pumped into twelve fountains, from which Black and white people drink together. Across lines of race, the new-city dwellers unite in worship, fellowship, and play. Notice the group of children with the ball in the bottom register!

For a framing device, Almon has used two wooden doors that bow out, as if the scene in all its fullness cannot be contained; as if the borders of the new city must bend to embrace the multitudes and their joy. The shape communicates an expansiveness that is the heart of God.

God is shown as majestic, mountain-like, and yet bearing a tender expression. The plastic beads on his forehead are printed with letters that read, “THE NEW HEAVEN,” and his eyes (not lit in this photo) are battery-powered light bulbs! He is, as John the Revelator tells us, the unending light dispelling all darkness.

Almon was born in 1938, so for about the first three decades of his life, he lived in a country where racial segregation was enforced legally in many states and socially in others. By and large, Blacks and whites were made to live in separate neighborhoods, attend separate schools, swim in separate pools, eat at separate restaurants, drink from separate water fountains, pass through separate public building entrances, wait in separate waiting rooms, sit in separate sections of the bus and the theater and even (woe is us) the church, and so on. Even after the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, mandating desegregation, racial prejudices and hostilities continued to persist, as they do today. And because sinful human beings create and run systems (criminal legal, economic, educational, medical, etc.), it’s no surprise that the sin of racism can be found there as well.

Almon longed to see racial justice and (re)conciliation, and he knew Jesus has the power to make it happen. Almon’s preaching ministry went hand-in-hand with his art making. Through both, he shared the good news that Jesus, through his life, death, and resurrection, calls us to a new way of being in the world, which involves repentance of sin and turning to the divine light of love that knows no bounds. His New Heaven envisions a world saved and transformed by Christ’s love, where power is shared equally, forgiveness sought and granted, and friendship is the order of the day, as is a shared rejoicing in the greatness of God. In The New Heaven, Black and white praise Jesus side-by-side, eat at the tree of life together, and put their lips to the same bubbling fount of living water.

And not only are relationships healed and humanity restored to its original harmony in the new heaven, but also personal sorrows and hardships are no more. Physically, mentally, emotionally, spiritually, socially, we flourish in the light of God that never dims.

For more on Leroy Almon, see this Art & Theology Lenten devotional post from earlier this year.

LISTEN: “Great Rejoicing” by Thad Cockrell, on To Be Loved (2009) | Performed by Rain for Roots, feat. Sandra McCracken and Skye Peterson, on Waiting Songs (2015)

There’s gonna be a great rejoicing (2×)

The troubles of this world

Will wither up and die

That river of tears made by the lonely

Someday will be dry

There’s gonna be a great rejoicingThere’s gonna be a great joy river (2×)

Questions of this world

Someday will be known

Who’s robbing you of peace

And who’s the giverThere’s gonna be a great joy river

Someday you will find me

Guarded in His fortress

Open heart and wings

That never touch the ground

Someday we will gather

In a grand reunion

Debts of this old world

Are nowhere to be found

Nowhere to be foundThere’s gonna be a great rejoicing (5×)

We are now halfway through Advent! Many of the songs featured in this Advent series, including today’s, appear on my Advent Playlist. I also have a companion Christmastide Playlist, which has been revised and expanded since last year to include some choral selections.