LOOK: Breaking Point, etc., by Rosa-Johan Uddoh

Rosa-Johan Uddoh is an interdisciplinary artist based in London who, “through performance, writing and multimedia installation, . . . explores places, objects and celebrities in British popular culture, and their effects on self-formation,” she writes on her website.

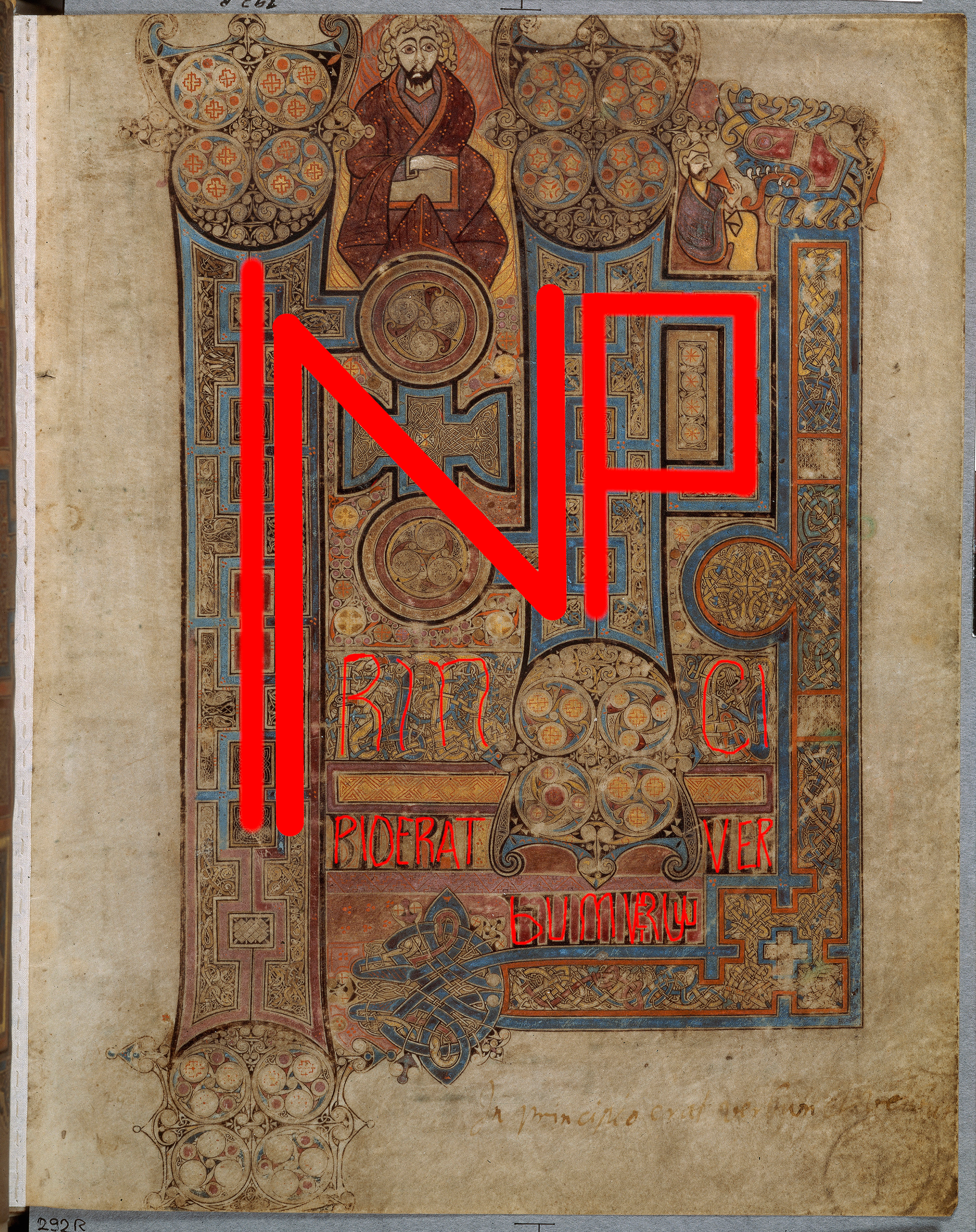

In her first institutional solo show, Practice Makes Perfect at Focal Point Gallery in Southend-on-Sea, she explored how the white European imagination constructed Blackness through the figure of Balthazar, who according to Christian tradition was one of the three magi who visited the infant Jesus, offering him the gift of myrrh. Since the fifteenth century Balthazar has typically been depicted as Black, as it was imagined that he came from Africa (whereas the other two magi were supposedly from Europe and Asia, the three known continents at the time). Uddoh notes that Balthazar is one of the first Black people of importance that British schoolchildren encounter, and in fact the first public performance she ever gave was as Balthazar in a primary-school Nativity play, a role she had been cast in by her teacher.

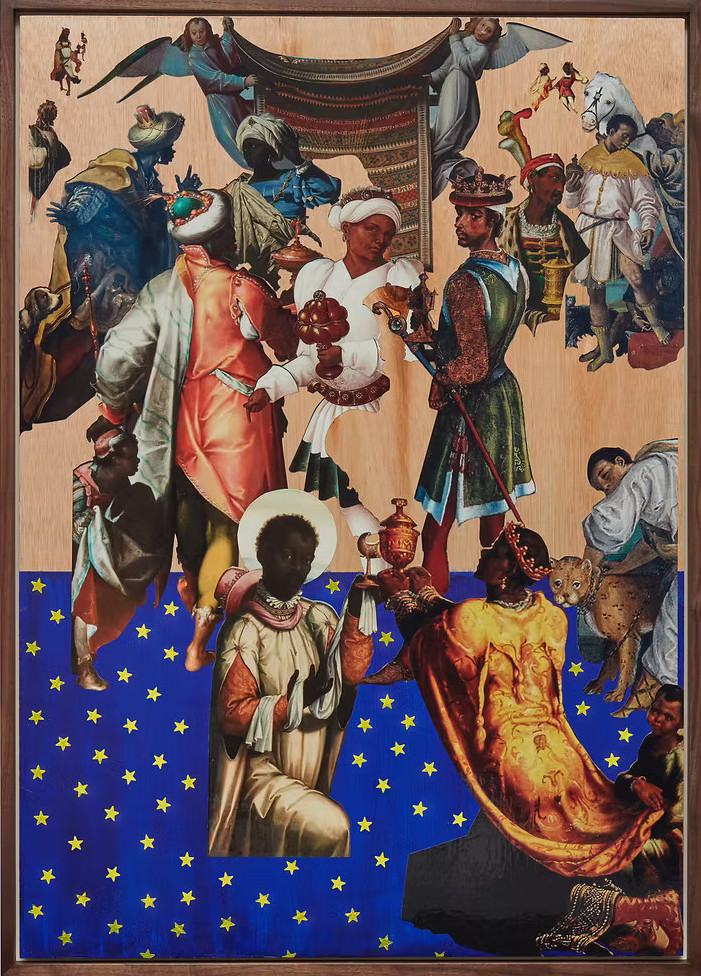

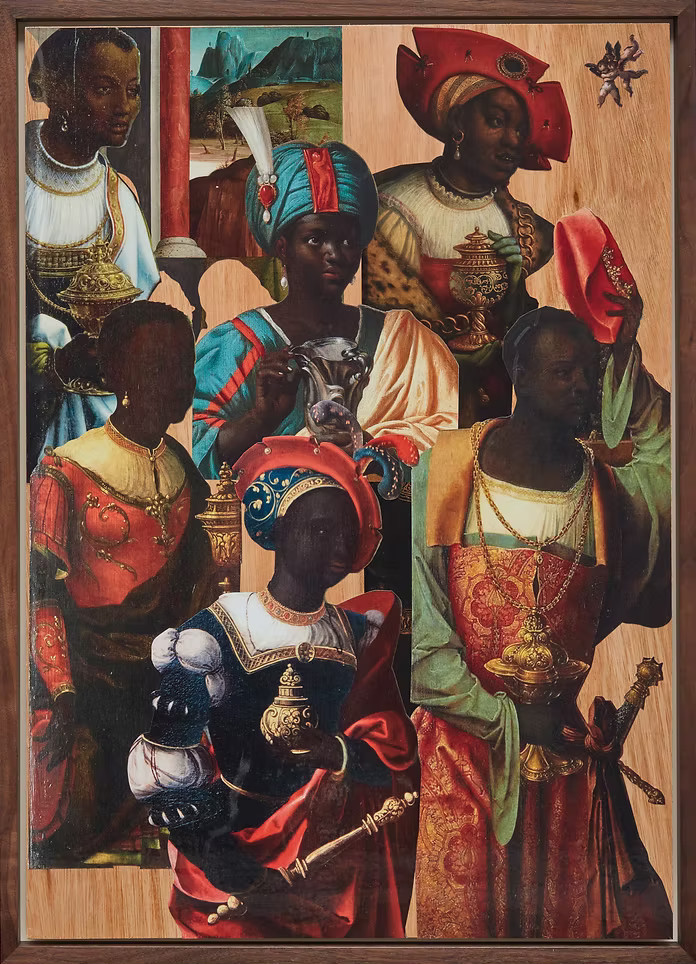

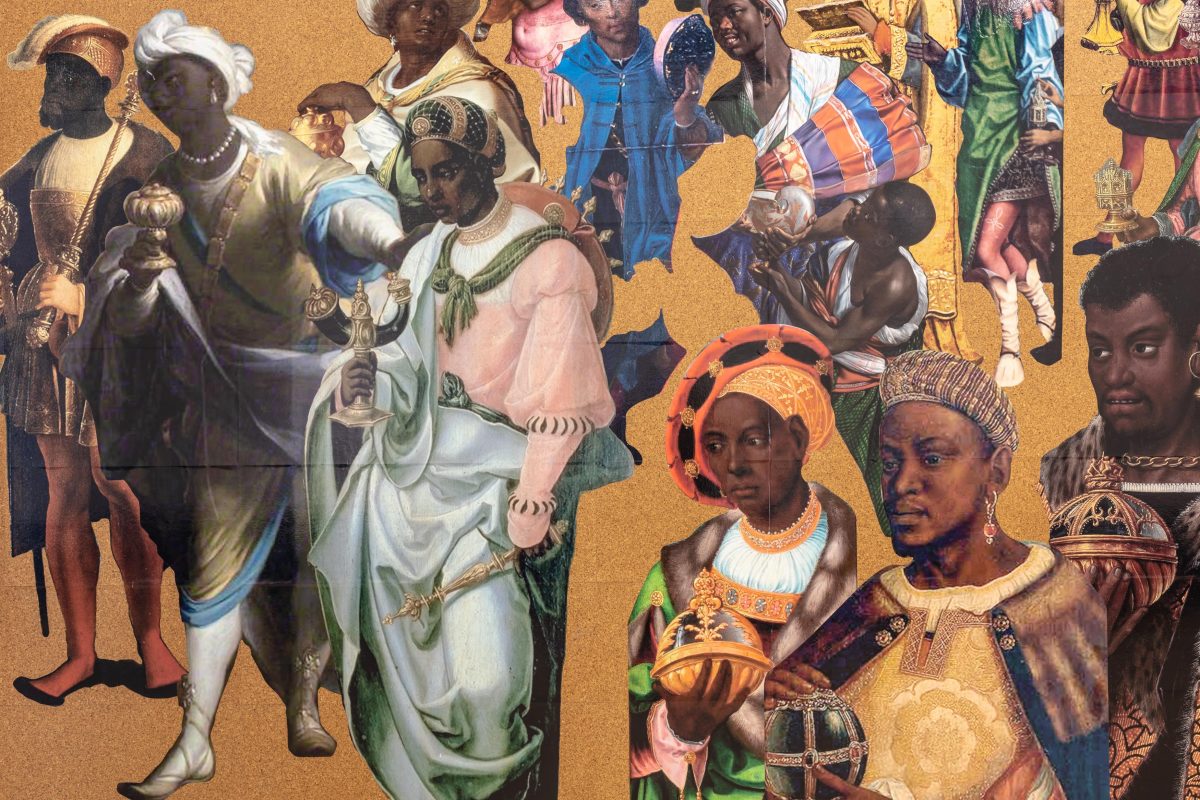

The centerpiece of the Practice Makes Perfect exhibition was Breaking Point, a billboard-sized mural that depicts 150 Black Balthazars extracted from European paintings from the late Middle Ages onward and rearranged into friendship groups. These groupings “allow Balthazar to escape the isolation associated with being the only Black character of importance in Christian iconography whilst also highlighting that the Black figures behind the artistic imagery were real sitters, which is also a testament to early African immigration into Europe, a phenomenon often overlooked in mainstream history.”

Installed on either side of Breaking Point was a scroll bearing a piece of experimental writing by Uddoh, titled Nativity. (She later performed this text in 2022 at the London art gallery Workplace, with Adeola Yemitan and Ebunoluwa Sodipo.) It opens, “In the beginning, they did the Nativity. Everyone in it was pink; well, the main characters anyway . . .”

In 2022 Uddoh expanded this body of work with another solo show, Star Power at Workplace. It featured the series You Can Go Ahead and Talk Straight to Me and I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance (scroll through select images below), the artworks made of acrylic and vinyl on board. The former title is a quote from Toni Morrison’s 1975 speech “A Humanist View,” given at Portland State University as part of a public forum on the theme of the American Dream. The latter is a quote from Sojourner Truth—she wrote the phrase on the bottom of a self-portrait she took, selling copies of it across America to raise funds for her abolitionist activism.

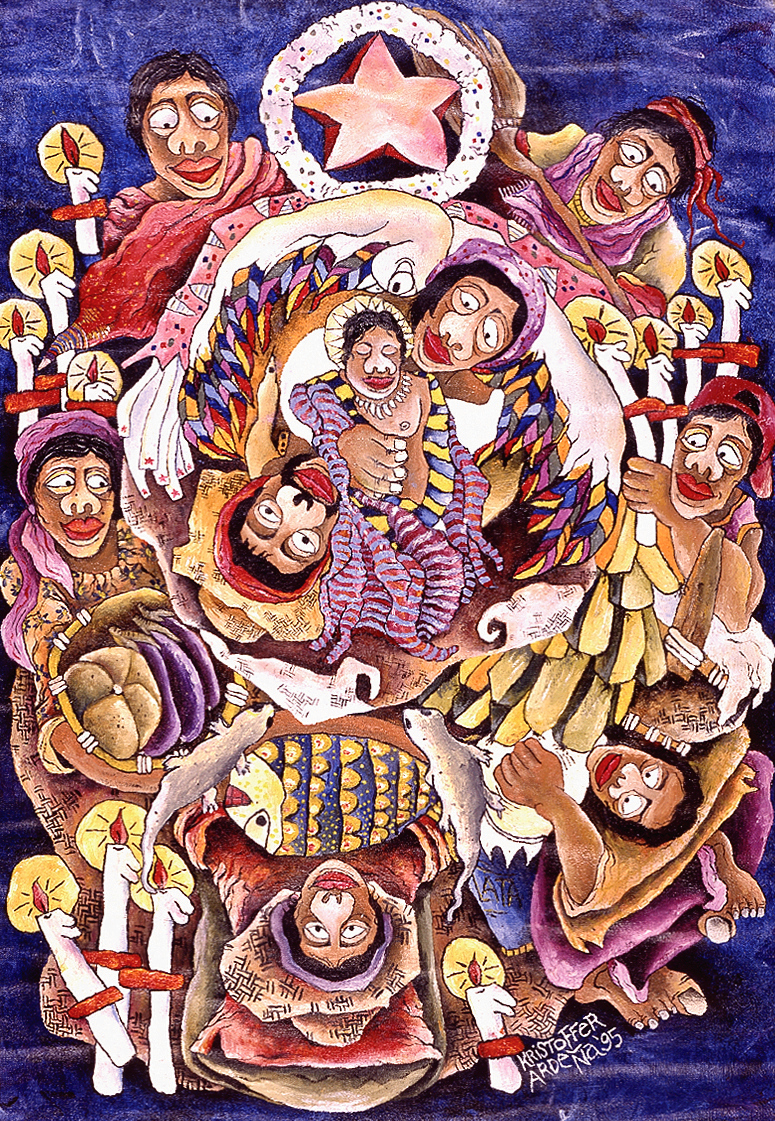

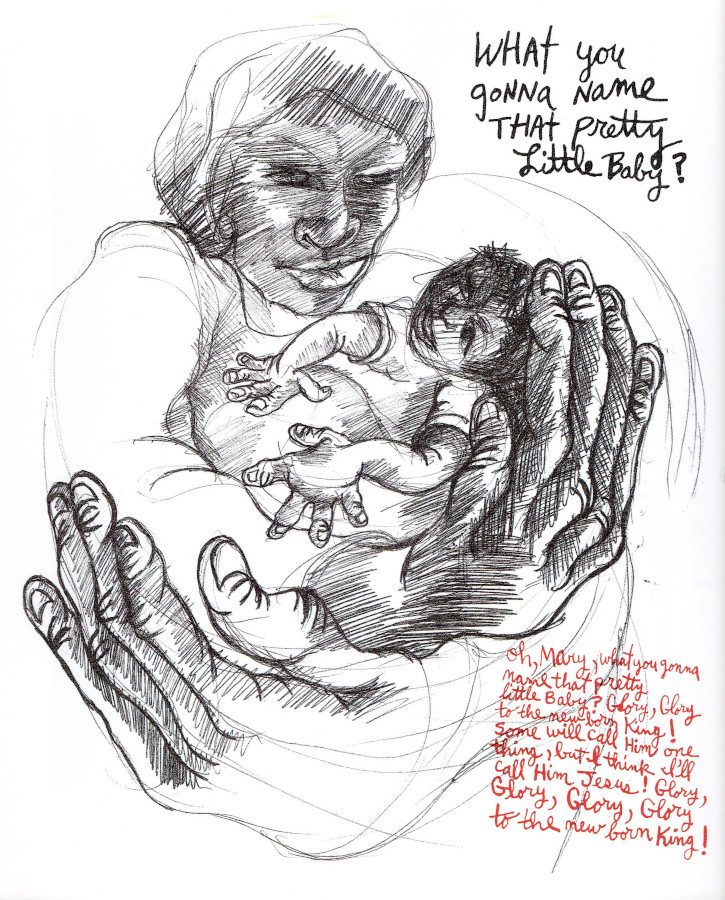

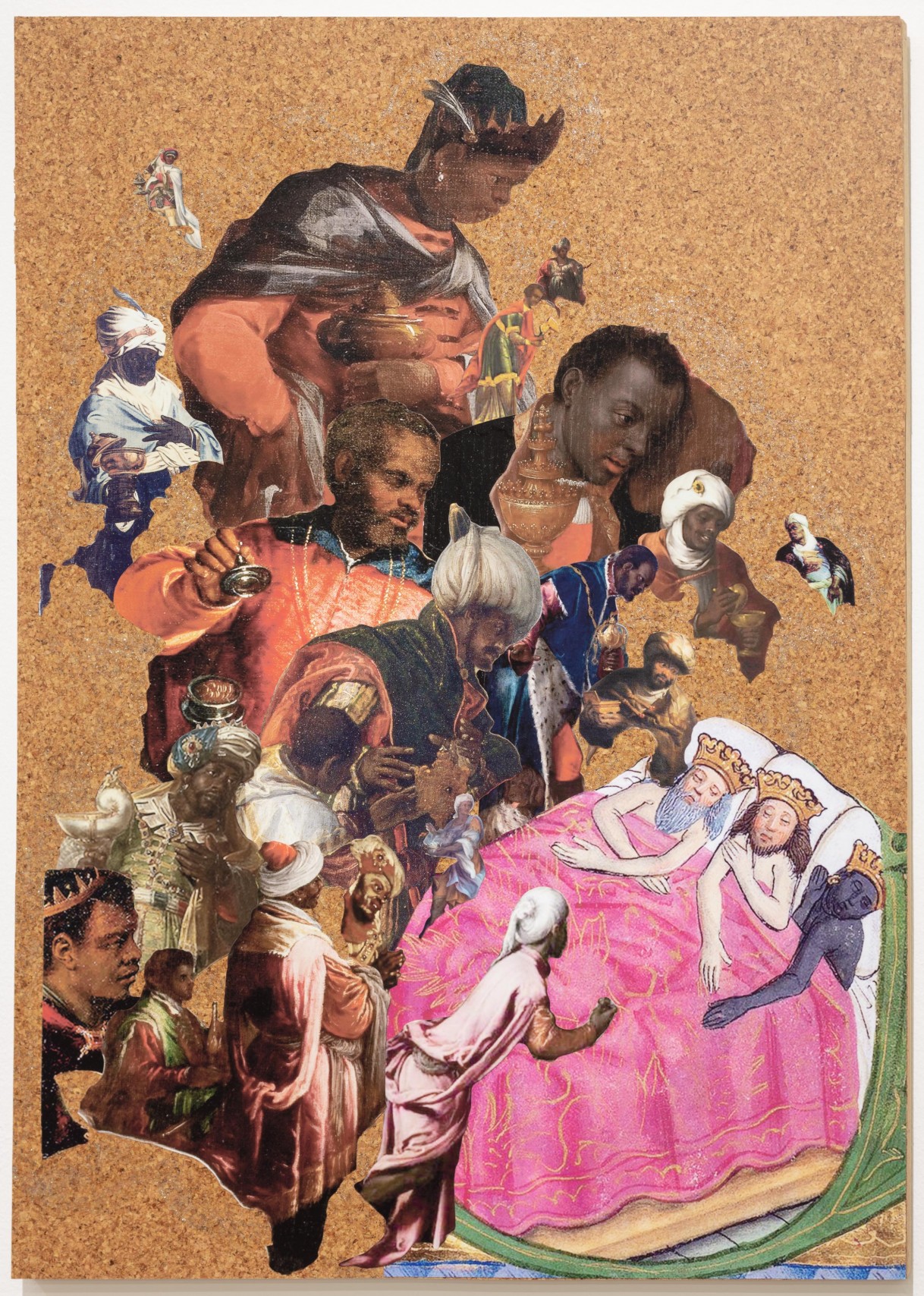

Lastly, here’s an amusing collage from Practice Makes Perfect:

The image of the three kings in bed is taken from the ca. 1480 Salzburg Missal. (In the original they’re inside an initial E, which introduces the text for the introit for the Feast of the Epiphany, “Ecce advenit dominator Dominus.”) In the Middle Ages it was common for artists to depict the magi in bed together when they receive the angelic warning not to reveal the location of the baby Jesus to King Herod, who intends to harm him (Matt. 2:12). There’s nothing sexual about it—it’s just a compositional practicality, to show the three men in one space, having the same dream at the same time.

In Uddoh’s playful remix, she has a slew of Balthazars leaning over the bed to wake up their sleeping comrade so that he can join them in a protest for racial justice.

LISTEN: The Ballad of the Brown King by Margaret Bonds, 1954, rev. 1960 | Words by Langston Hughes, 1954/60 | Arranged by Malcolm J. Merriweather for strings, harp, and organ, 2018 | Performed by the Dessoff Choirs and Orchestra, dir. Malcolm J. Merriweather, on Margaret Bonds: The Ballad of the Brown King and Selected Songs, 2019 (soloists: Laquita Mitchell, soprano; Noah Stewart, tenor; Lucia Bradford, mezzo-soprano; Ashley Jackson, harpist)

I encourage you to listen to all nine movements! (The piece is twenty-five minutes long.) But if you want just a taste for now, here are two selections: movements 1 and 7.

I. Of the Three Wise Men

Of the three wise men who came to the King

One was a brown man, so they sing

Alleluia, AlleluiaOf the three wise men who followed the star

One was a brown king from afar

Alleluia, Alleluia. . .

VII. Oh, Sing of the King Who Was Tall and Brown

Oh sing of the king who was tall and brown

Crossing the desert from a distant town

Crossing the desert on a caravan

His gifts to bring from a distant land

His gifts to bring from a palm tree land

Across the sand by caravan

With a single star to guide his way to Bethlehem

To Bethlehem where the Christ child layOh sing of the king who was tall and brown

And the other kings that this king found

Who came to put their presents down

In a lowly manger in Bethlehem town

Where the King of kings a babe was found

The King of kings a babe was found

Three kings who came to the King of kings

And one was tall and brown

Margaret Bonds (1913–1972) was an African American composer, pianist, arranger, and teacher, best remembered for her popular arrangements of African American spirituals and her frequent collaborations with her friend Langston Hughes, especially the cantata The Ballad of the Brown King.

Dedicated to Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., The Ballad of the Brown King honors the African king Balthazar of Christian tradition, a figure extrapolated from the Gospel of Matthew’s account of the “wise men from the east” who came to worship the Christ child and bestow gifts. Bonds wanted to celebrate the wisdom and devotion of this dark-skinned brother, and his active presence at the Nativity, giving “the dark youth of America a cantata which makes them proud to sing,” she wrote in a letter.

She commissioned Hughes to write the libretto. She wrote to him, “It is a great mission to tell Negroes how great they are.” Remember, this was at the burgeoning of the civil rights movement. There were very few images of Black wealth and admirability being projected by mainstream culture at the time. Balthazar was an exception.

The Grammy-nominated conductor Malcolm J. Merriweather, who fueled a revival of interest in Bonds’s work (more on him below), said in an interview with Presto Music:

Regardless of the racial accuracy, this narrative [of an African king participating in the story of Christ’s birth] gives African Americans a positive image rarely portrayed in history, books, and art. A brown sovereign, traveling in majesty and splendor? It is unheard of. African Americans are not just descendants of slaves; we come from great kings or queens that ruled kingdoms with sophisticated political and economic systems on the continent of Africa.

The initial version of The Ballad of the Brown King premiered in December 1954, but Bonds and Hughes later revised and expanded it. The new version premiered December 11, 1960, at the Clark Auditorium of the YWCA in New York, sung by the Westminster Choir of the Church of the Master. The concert was presented as a benefit for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

The cantata is made up of nine movements with parts for soprano, tenor, baritone, and choir. Stylistically, the work has been described as neo-Romantic, but it also draws on gospel, jazz, blues, and calypso traditions.

The only commercial recording ever made of it is the one released by Avie Records in 2019. Newly arranged by Malcolm J. Merriweather, the piece is performed there by the Dessoff Choirs and Orchestra under Merriweather’s direction.

Bonds had scored the cantata for full orchestra—brass, woodwinds, strings (including harp), and percussion. But because hiring an orchestra of that size is expensive and he wants to see this work more widely performed, including in church contexts, Merriweather arranged the piece for a pared-down ensemble of harp, strings, and organ, omitting the winds and brass (whose parts he essentially absorbed into the new organ part). He also enlivened the harp part to add texture.

For more context on Bonds and on this most popular cantata of hers, here’s a great thirty-minute conversation between John Banther and Evan Keeley from a 2022 episode of the Classical Breakdown podcast, produced by WETA Classical in Washington, DC: