LOOK: Hope by Ulrich Barnickel

This is the last of fourteen monumental sculptures situated along the former inner German border that separated Soviet-occupied East Germany and Allied-occupied West Germany from 1952 to 1990. Stretching from Hesse to Thuringia, this highly militarized frontier consisted of high metal fences, barbed wire, alarms, watchtowers, and minefields, a literal iron curtain that divided families, friends, and neighbors.

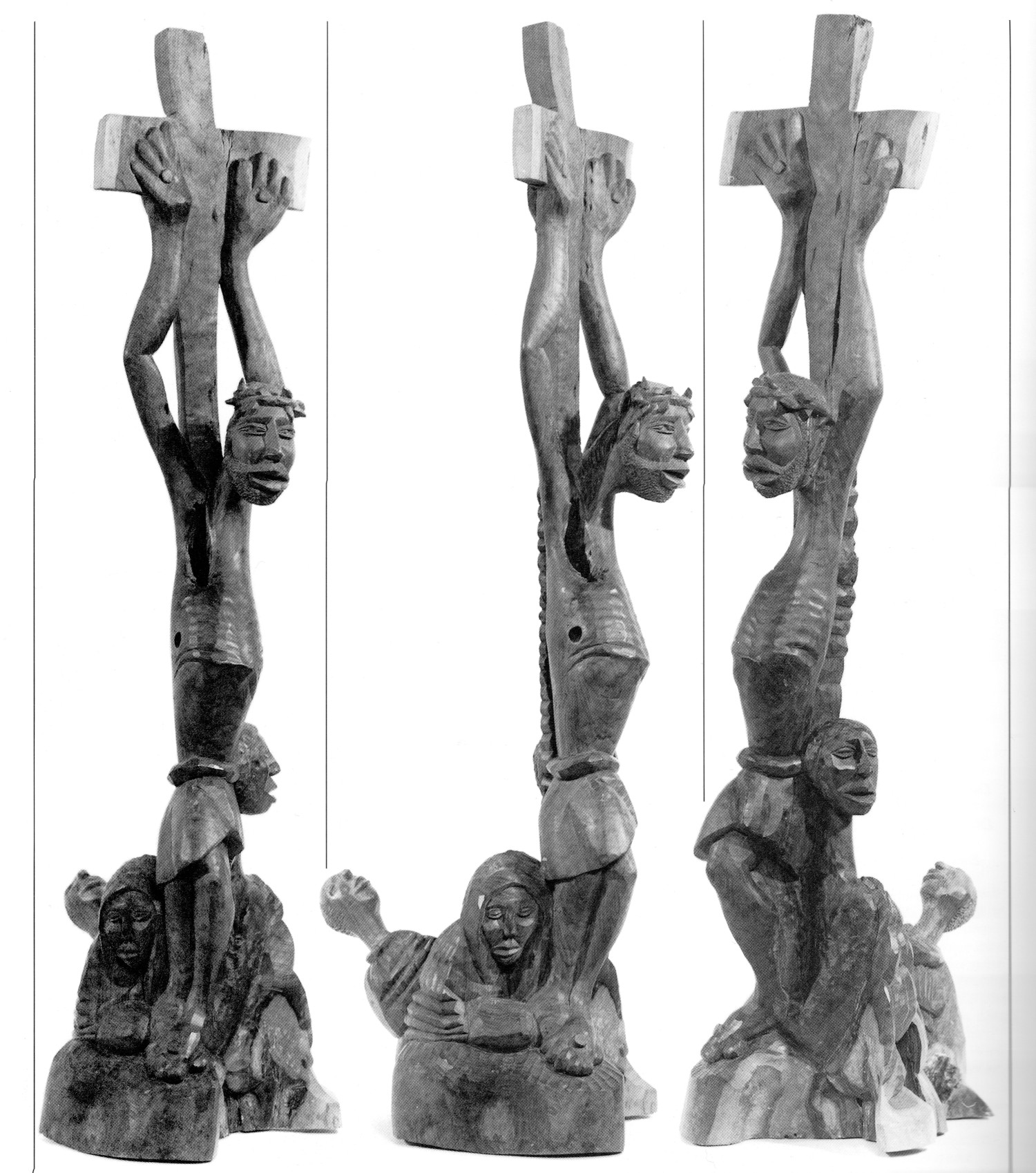

In 2009, the Point Alpha Foundation, founded to preserve the historic site as a memorial, commissioned German metal sculptor Ulrich Barnickel to create an artwork as part of the memorial. He decided to draw on the traditional fourteen Stations of the Cross, connecting the suffering of Jesus to that of the people on the inner German border under Communism. Collectively titled Path of Hope, his fourteen iron sculptures cover 1,400 meters of ground (scaling down the 1,400 kilometers of the former border). All but the last are figurative, representing Jesus falling, meeting his mother, being nailed to the cross, and so on. They contain artifacts from or references to German Cold War era history, such as a vintage steel helmet hanging on Pilate’s chair, or the grenade and the trench that Jesus stumbles over.

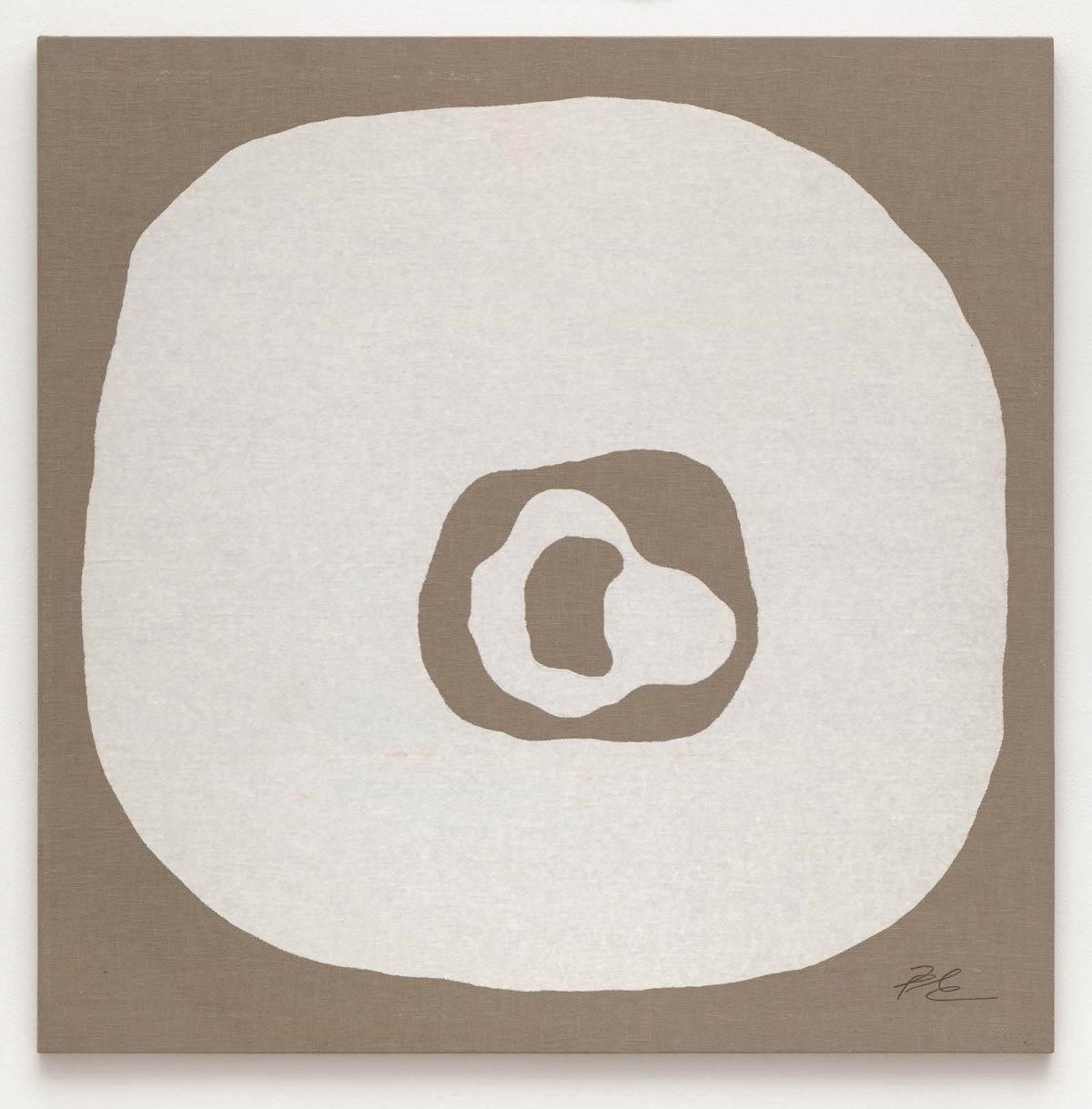

The final station, titled Hope, is a threefold open doorway. After all the heaviness of the previous thirteen stations, we get this breather. Here’s what the doors say to me: Invitation. Possibility. The fourteenth station of the cross is traditionally where Christ is buried in his tomb. But instead of a dead body on a slab or a sealed-up cave, Barnickel gives us an open frame, a door ajar, a view of sky. It alludes to resurrection. Jesus walked through death and came out the other side. And so can we.

While the Path of Hope is a vehicle for remembering, lamenting, and healing from the collective traumas of war and political violence and oppression, it can also speak to personal losses, to any individual’s journey of grief. It’s an invitation to acknowledge the pain we carry but also to see beyond it to the Better Day that is coming, as well as to embrace the life before us here and now. The doors ask us to unburden ourselves of whatever weight is crushing us and to be renewed. (Notice the crown of thorns, an emblem of suffering, left hanging on the corner of the final threshold.) To follow the Man of Sorrows, who walks beside us in our own sorrow, from death into life.

For those accompanying a loved one to the door of death, or who have had a loved one suddenly snatched through, may Barnickel’s Hope meet you in your grieving, filling you with soft consolations of a Love stronger than death, a Love who, once buried, became on the third day the firstfruits of the resurrection harvest.

LISTEN: “Alleluia, Christ Is Risen Once Again” by Tara Ward, written 2007, performed 2020

Waking up to tragic dawn

Not comprehending what is going on

Alleluia, Christ is risen once againAnd it frames a hollow place

Lost dreams and accolades

Alleluia, Christ is risen once againAlleluia, Christ is risen

Though the walls of castles fall

Alleluia, he is risen for us allFrom these sights the shadows light

In an overwhelming night

Alleluia, Christ is risen once againHopes fly from us every day

Fear reigns far and so does hate

Alleluia, Christ is risen once againAlleluia, Christ is risen

Though the gates of all this war

Alleluia, Christ is risen evermoreAlleluia, God is able

To complete the life you led

Alleluia, Christ is risen from the deadAlleluia, he is risen once again

From the sorrow you have fled

You have joy around your head

Alleluia, Christ is risen once againAnd as from earthly trials you fly

You leave sadness when you die

Alleluia, Christ is risen once againAlleluia, Christ is risen

And the life you’re living now

Alleluia, all’s forgiven somehowAlleluia, there is beauty

When I think of you, joy I feel

Alleluia, in my sadness, faith is realAlleluia, Christ is risen once again

Alleluia for you, my friend

Tara Ward [previously] wrote this song during the 2007 Easter season when two tragedies struck within a week of each other. On April 16, a mass shooter opened fire at Virginia Tech, killing thirty-two people, and on April 21, Ward’s friend Liz Duncan was fatally struck by a car while jogging. In the second half of the song, Ward addresses Duncan in the second person, rejoicing through tears that she has entered a state of joy and rest and will one day be raised, body and soul.

Ward returned to the song for Easter 2020 following the death that March of another friend and the initial outbreak of COVID-19. “I was trying to think of what I would sing if I was still working at a church, looking for honest songs to sing on Easter, and this one came up,” she writes on the YouTube video description.

The Nashville community, and America at large, is still reeling from the March 27 shooting at Covenant School that left seven dead, the 131st mass shooting in the US this year. I can only imagine the absolute devastation and rage a parent would feel upon learning that the child they dropped off at school that morning would not be coming home because they were gunned down with an assault rifle.

As I listen to this song, I think, too, of Leslie Bustard, a writer and book publisher, a luminary in the art and faith sphere, who, less than two months after hosting an amazing Square Halo conference on the theme of “ordinary saints,” is now in hospice with late-stage cancer.

Sometimes all the exuberance of Easter can seem disjunctive with the bleak state of the world or our own present circumstances. Christ is risen, but death is still a reality, and it’s still painful. Quiet and aching, this song gives space to grief while also confessing this central Christian doctrine: that Jesus rose from the dead, giving life to all who will receive it. Of course, that doesn’t mean Christians are exempt from experiencing physical death—we will all one day go to the grave—nor from the grief that follows in the wake of a loved one’s passing.

But what Ward’s song helps us do is sing “alleluia” in our sadness, because Christ’s resurrection life is at work in those who have passed on in him, and it’s at work in those of us who walk through the valley of death’s shadow here on earth. The “once again” language—“Christ is risen once again”—indicates that Jesus’s historical rising has ongoing implications, its efficacy extending to every new place of death.