In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. . . .

And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth. . . . No one has ever seen God. It is the only Son, himself God, who is close to the Father’s heart, who has made him known.

—John 1:1–3, 14, 18 (NRSV)

He is the reflection of God’s glory and the exact imprint of God’s very being.

—Hebrews 1:3 (NRSV)

His birth is twofold: one, of God before time began; the other, of the Virgin in the fullness of time.

—Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures XV

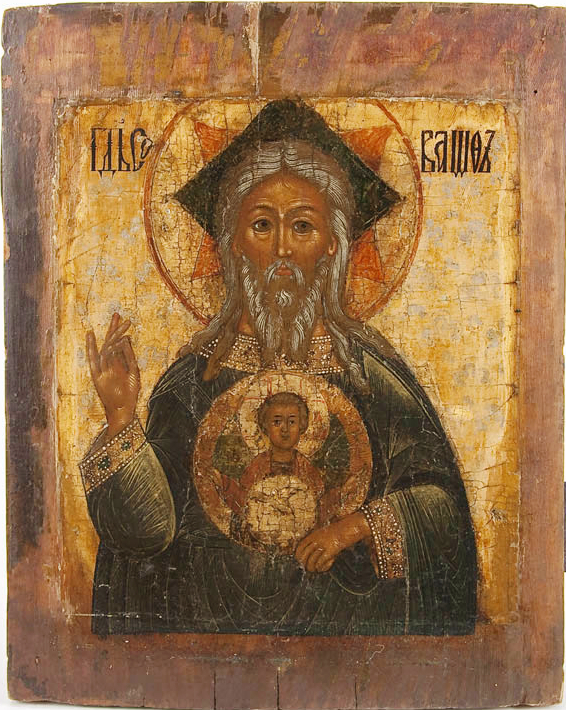

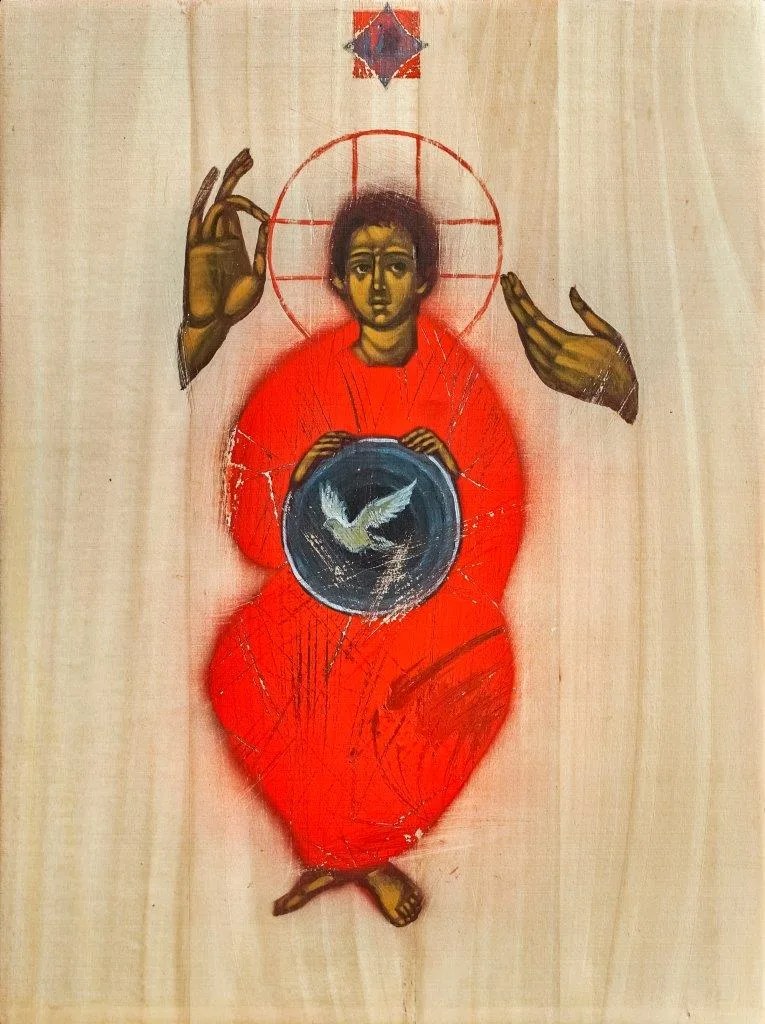

LOOK: Two Paternity icons

The Otechestvo—“Fatherhood” or “Paternity”—icon shows God the Father (Lord Sabaoth, as he is titled in Russian Orthodoxy) as an old man with Christ Emmanuel (Jesus in child form) seated on his lap or encircled by his “womb,” and the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove hovering before his chest. The eight-pointed slava (“glory”) behind the Father’s head signifies his eternal nature, shared by all three persons. His right hand forms the Greek letters IC XC, abbreviating “Jesus Christ.”

Here are two examples of this Trinitarian image—one from the eighteenth century, and one from just two years ago, which I encountered through the OKSSa [previously] exhibition The Father’s Love.

The Polish artist Sylwia Perczak (IG @perczaksylwia) titles her icon after John 1:18: “No one has ever seen God. It is the only Son, himself God, who is close to the Father’s heart, who has made him known” (NRSV). The King James Version contains the lovely phrasing “the only begotten Son . . . is in the bosom of the Father.”

Perczak chooses to keep God the Father, who is incorporeal, out of frame, with the exception of his hands, which gesture to the Son, who holds the Spirit.

Thank you to David Coomler and his Russian Icons blog for introducing me to this icon type.

(Related post: “Begotten ere the worlds began”)

LISTEN: “In splendoribus sanctorum” by James MacMillan, 2005 | Performed by the Gesualdo Six, dir. Owain Park, feat. Matilda Lloyd, 2020; released on Radiant Dawn, 2025

In splendoribus sanctorum, ex utero, ante luciferum, genui te. [Psalm 109:3 Vulgate]

English translation:

In the brightness of the saints: from the womb before the day star I begot you. [Psalm 109:3 Douay–Rheims Bible]

Written for the Strathclyde University Chamber Choir, the Strathclyde Motets are a collection of fourteen Communion motets for SATB choir by the Scottish composer James MacMillan. “In splendoribus sanctorum” (In the Brightness of the Saints / Amid the Splendors of the Heavenly Sanctuary) is for Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve and includes a trumpet obbligato.

The Latin text is from Psalm 109 in the Vulgate (numbered Psalm 110 in Jewish and Protestant Bibles), a royal psalm that looks forward to the Messiah. The verse is interpreted by Christians as referring to how Christ existed before the dawn of creation, in eternity, and was begotten by the Father; he is the Son of God.

The verse didn’t ring a bell from my many readings of the Psalms over the years—and that’s because it’s from a different manuscript tradition than the Bible translations I typically use (KJV, NRSV, NIV, ESV).

See, the Vulgate, from the late fourth century, is based on the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures produced in Alexandria in the third through first centuries BCE; so is the major Catholic translation of the Bible into English from 1610, the Douay–Rheims. But Protestant and ecumenical translations are based on the Masoretic Text, the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the twenty-four books of the Jewish canon. The Septuagint and the Masoretic Text contain some textual variants, and this verse is one of them. (Learn more on the Catholic Bible Talk blog.)

Here’s how the verse reads in the New Revised Standard Version:

Your people will offer themselves willingly

on the day you lead your forces

on the holy mountains.From the womb of the morning,

like dew, your youth will come to you.

The meaning of the Hebrew is obscure, but the phrase “womb of the morning” probably refers to dawn, and “your youth” to the soldiers at the Messiah’s command.

Anyway, I felt I had to explain why if you look up the verse, you might have trouble finding it, depending on which Bible you use.

The Catholic and Orthodox Churches have chosen the “from the womb before the day star I begot you” variant in their liturgies. I love its poetic theology! They use the verse to support the doctrine, taught by all three branches of Christianity, of the eternal generation of the Son—who is “God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made,” as the Nicene Creed puts it.

By including this verse in its first liturgy of Christmastide, celebrated the night of Christmas Eve, the Catholic Church underscores that Jesus is of the same essence as God the Father. Mary, crucially, gives birth to Jesus, flesh of her flesh—but the Son is generated by the Father before all ages.

To hear “In splendoribus sanctorum” in Old Roman chant from the sixth century, click here.