In the days of King Herod of Judea, there was a priest named Zechariah, who belonged to the priestly order of Abijah. His wife was a descendant of Aaron, and her name was Elizabeth. Both of them were righteous before God, living blamelessly according to all the commandments and regulations of the Lord. But they had no children, because Elizabeth was barren, and both were getting on in years.

Once when he was serving as priest before God and his section was on duty, he was chosen by lot, according to the custom of the priesthood, to enter the sanctuary of the Lord and offer incense. Now at the time of the incense offering, the whole assembly of the people was praying outside. Then there appeared to him an angel of the Lord, standing at the right side of the altar of incense. When Zechariah saw him, he was terrified; and fear overwhelmed him. But the angel said to him, “Do not be afraid, Zechariah, for your prayer has been heard. Your wife Elizabeth will bear you a son, and you will name him John. You will have joy and gladness, and many will rejoice at his birth, for he will be great in the sight of the Lord. He must never drink wine or strong drink; even before his birth he will be filled with the Holy Spirit. He will turn many of the people of Israel to the Lord their God. With the spirit and power of Elijah he will go before him, to turn the hearts of parents to their children, and the disobedient to the wisdom of the righteous, to make ready a people prepared for the Lord.” Zechariah said to the angel, “How will I know that this is so? For I am an old man, and my wife is getting on in years.” The angel replied, “I am Gabriel. I stand in the presence of God, and I have been sent to speak to you and to bring you this good news. But now, because you did not believe my words, which will be fulfilled in their time, you will become mute, unable to speak, until the day these things occur.”

Meanwhile the people were waiting for Zechariah, and wondered at his delay in the sanctuary. When he did come out, he could not speak to them, and they realized that he had seen a vision in the sanctuary. He kept motioning to them and remained unable to speak. When his time of service was ended, he went to his home.

After those days his wife Elizabeth conceived, and for five months she remained in seclusion. She said, “This is what the Lord has done for me when he looked favorably on me and took away the disgrace I have endured among my people.”

—Luke 1:5–25

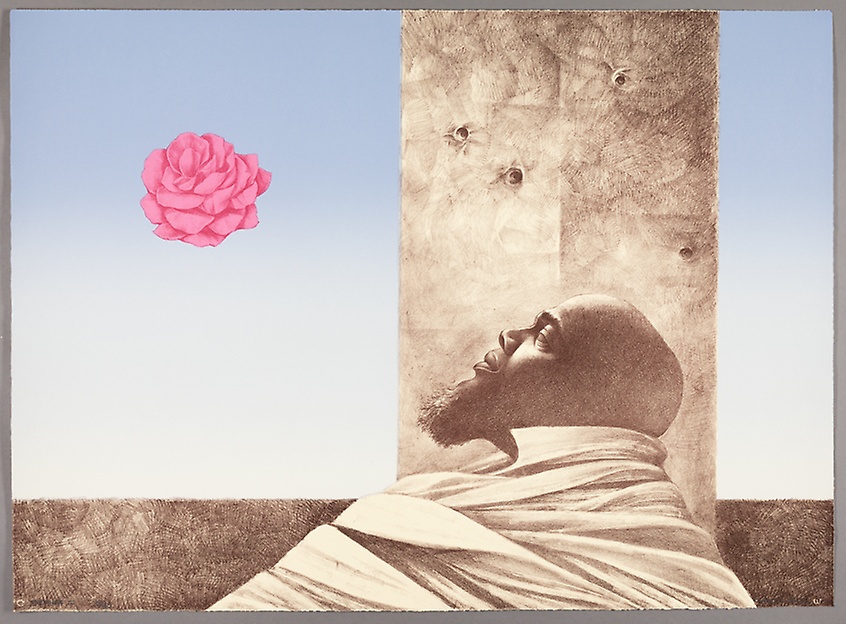

LOOK: Zacharias and Elizabeth by Stanley Spencer

The modern British artist Stanley Spencer is famous for his paintings depicting the New Testament narrative unfolding in his small village of Cookham on the River Thames. The English countryside was a balm for him after his return from World War I, as in it he sensed the Divine. “Quite suddenly I became aware that everything was full of special meaning, and this made everything holy,” he said. “The instinct of Moses to take his shoes off when he saw the burning bush was very similar to my feelings. I saw many burning bushes in Cookham. I observed the sacred quality in the most unexpected quarters.”

Like Spencer’s other biblical paintings, Zacharias and Elizabeth features people and places that were familiar to him. Tate Britain, the museum that owns the work, describes it like this:

In the foreground of the composition is Zacharias, an elderly male figure dressed in white who is holding a pair of tongs over a flame, while another aged male, also wearing white – the Archangel Gabriel – approaches him stealthily from behind. The figure of Zacharias is also repeated in the background of the painting: behind a wood and metal fence, staring blankly outward while the auburn-haired Elizabeth stands to his right with her arms outstretched. A large, smooth, curved wall divides the painting vertically, separating these two scenes. The figure of Elizabeth appears again behind the wall, with only her upper body visible. Two further figures are also depicted in the painting: a gardener who resembles traditional representations of both Jesus and John the Baptist is seen at the right dragging an ivy branch, a conventional symbol of everlasting life and Resurrection, and an unidentified woman wearing a dark claret dress kneels behind a gravestone while touching the curved dividing wall with her right hand.

Art critic and curator Sarah Milroy interprets this woman in the left midground as a surrogate for Spencer. She writes,

In childhood, Spencer believed that the Bible stories his father read aloud to the family at night could be glimpsed in Cookham, if only he could get a peek over top of the cottage walls. The little girl with her feverish, ember-red eyes, spying on the holy scene from her hiding place behind the curved white wall, serves as a stand-in for the artist himself.

For another meditation I wrote on a Spencer painting, see “Resurrection Now,” part of the Visual Commentary on Scripture project.

LISTEN: “Zechariah and the Least Expected Places” by Ben Thomas, on The Bewildering Light by So Elated (2008)

Jerusalem and the holy temple filled with smoke

Zechariah shuns the news from the angel of hope

Stuck behind an incense cloud of religion and disappointmentGod keeps slipping out of underneath rocks

In alleys off the beaten path

Open both your eyesProphets and kings and poets can contribute their work

Just like eggs in a nest are alive with the promise of birds

But the Lord of creation will not be subjected to expectationGod keeps slipping out of underneath rocks

In alleys off the beaten path

Open both your eyesElizabeth, barren, her knees black and dirty like coal

Her consistent prayers float to the sky and revive her soul

God, we will wait though we don’t understand your redemptive storyGod keeps slipping out of underneath rocks

In alleys off the beaten path

Open both our eyes