There’s a river somewhere

That flows through the lives of everyone

I know it flows through the valleys

And the mountains and the meadows of time

Yes, it doThere’s a star in the sky

That shines in the lives of everyone

You know it shines in the valleys

And the mountains and the meadows of time

Yes, it doThere’s a voice from the past

That speaks through the lives of everyone

You know it speaks through the valleys

And the mountains and the meadows of time

Yes, it doThere’s a smile in your eyes

That brightens the lives of everyone

It brightens the valleys

And the mountains and the meadows of time

Yes, it doThere is a short song of love

That sings through the lives of everyone

You know it sings through the valleys

And the mountains and the meadows of time

Yes, it doThere’s a river somewhere

That flows through the lives of everyone

I know it flows through the valleys

And the mountains and the meadows of time

Yes, it do

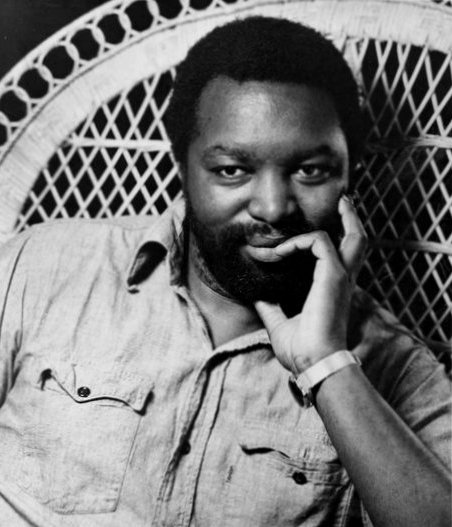

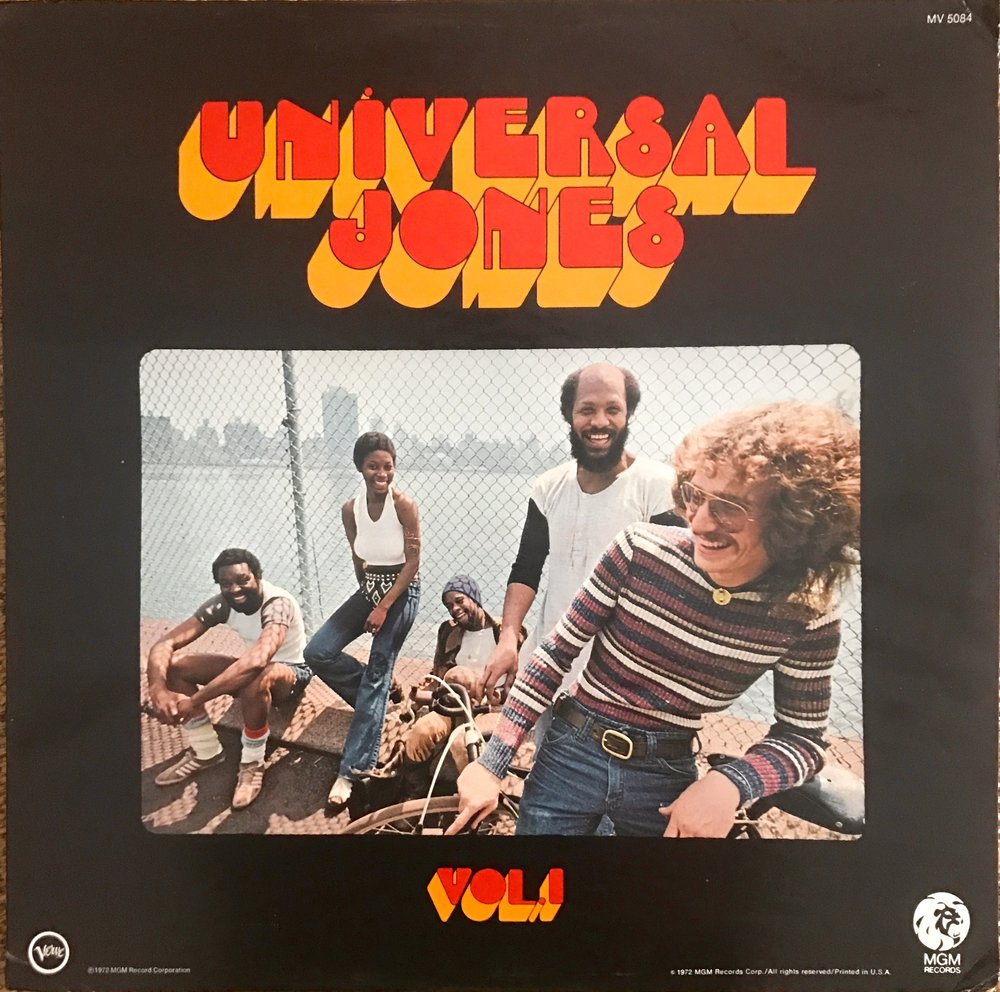

The folk-funk song “River” is by the American singer-songwriter and music producer Eugene McDaniels (1935–2011). He first recorded it with his band Universal Jones on a self-titled album (the group’s only output) in 1972, and he recorded it again, with a synth, on his solo album Natural Juices in 1975.

McDaniels grew up in Omaha, Nebraska, singing gospel music in church. He gained fame in the early 1960s as a clean-cut soul singer—he went by “Gene” at the time—and then surprised everyone in 1970 and 1971 with Outlaw and Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse, containing antiwar, antiestablishment songs performed in a much more experimental style. Universal Jones (1972) is innocuous by comparison, though it still embraces the counterculture. The genres of folk, rock, jazz, gospel, soul, funk, and even proto-rap—often creatively mixed—are all represented in McDaniels’s oeuvre.

In the Bible, water connotes blessing, refreshment, life, hope, and abundance. “Flowing streams,” writes the Rev. J. Stafford Wright, “are parables of the flowing life of God.” Wright was referring in particular to one of Ezekiel’s visions, where an unnamed guide leads the prophet through a river that issues forth from the temple in Jerusalem (Ezek. 47:1–12). The guide says,

This water flows toward the eastern region and goes down into the Arabah, and when it enters the sea, the sea of stagnant waters, the water will become fresh. Wherever the river goes, every living creature that swarms will live, and there will be very many fish once these waters reach there. It will become fresh, and everything will live where the river goes.

He then goes on to describe the verdant trees on either side of the riverbank:

Their leaves will not wither nor their fruit fail, but they will bear fresh fruit every month, because the water for them flows from the sanctuary. Their fruit will be for food and their leaves for healing.

Sounds a lot like John’s eschatological vision in Revelation 22, where a river flows down from God’s throne, watering the tree of life, which is for the healing of nations. There are also similar passages in the Minor Prophets: “A fountain shall flow from the house of the LORD” (Joel 3:18); “And in that day it shall be that living waters shall flow from Jerusalem” (Zech. 14:8). God is understood as the source of these waters, which signify an invisible, spiritual reality.

(Related posts: https://artandtheology.org/2022/04/02/lent-28/; https://artandtheology.org/2022/12/11/advent-day-15-great-joy-river/)

When Jesus comes onto the scene, he talks about “rivers of living water” flowing out of the hearts of believers (John 7:38–39), “spring[s] of water welling up to eternal life” (John 4:13–14). God dwells in humanity, and thus the life God gives springs up from within us and vitalizes the wider world.

I don’t know whether McDaniels had any of these biblical texts in mind when he wrote “River.” But a river, a star, a voice, a song of love—these signal to me the Divine moving, shining, speaking, singing into the lives of humanity. Through the ups and downs of history, the ancient will has worked and is continuing to work, revealing itself to those who look, listen, and follow. Ecclesiastes 3:11 says that God has “set eternity in the human heart.” We possess a moral consciousness and spiritual yearning.

To me, “River” is about recognizing the blessing poured out on the world from the heart of God, about tuning in to the unseen truths embedded in the fabric of the universe. It speaks of God’s all-brightening smile (God’s pleasure in his creation), his whispers of our belovedness, and the river-flow of his goodness.

The song has been covered a handful of times over the years and across the globe, including by:

- Roberta Flack (1973)

- Joe Simon (1973)

- Lenny Williams (1974)

- Sidsel Endresen and Bugge Wesseltoft (1998) [live]

- Grażyna Auguścik (2001)

Further, in 1975 the California bluesman J. C. Burris adapted it both lyrically and musically and recorded it under the title “River of Life” on his album Blues Professor:

Bernice Johnson Reagon, a song leader and civil rights activist, uses Burris’s lyrics in her cover on River of Life: Harmony One (1986), overdubbing her voice singing multiple parts in an a cappella tour de force:

There’s a river somewhere

That flows through the life

Of everyone

And it flows through the mountains

And down through the meadow

Under the sunThere’s a star in the sky

That brightens up the life

Of everyone

They can see the life of happiness

Along with the future

Of the lonely oneYes, it is

There’s a voice from the valley

That speaks to the mind

Of everyone

And it talks about the future

Along with the joy

Of the sorrowed onePut a smile on your face

And brighten up the day

For everyone

And live your life of happiness

Along with the sick and lonely

And sorrowed oneYes, it is

There’s a river somewhere

That flows through the life

Of everyone

And it flows from the mountain

Down through the meadow

Under the sunThere’s a sky full of diamonds

That brightens up the life

Of everyone

Then they can see the life of happiness

Along with the future

Of the lonely oneYes, it is

The main revision by Burris comes at the end of each verse, where he mentions the lonely, the sick, and the sorrowful. They have a special place of belonging in God’s heart and plans. Jesus’s ministry was to such as these. Blessed are the poor and those who mourn, he said, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Burris encourages us to come alongside those who are hurting with love and inclusion, and to look with them into God’s promised future, where the oppressed are liberated, the sick are healed, the silenced go out singing, and mourning is turned to dancing. Contra the cynicism of “the Preacher” who penned Ecclesiastes, there is something new under the sun! For those with eyes to see it, God is in the process of making all things new (Rev. 21:5).