POEM SERIES: “Twelve Days of Advent” by Kate Bluett: This year on her blog, writer Kate Bluett [previously] is publishing a series of original metrical verses based loosely on the cumulative song “The Twelve Days of Christmas.” She calls it the Twelve Days of Advent and through it explores the theology of Christ’s coming. I love this creative, sacred spin on the popular seasonal ditty! Here’s where the series currently stands (my favorite poems are in boldface):

- “A Partridge in a Pear Tree”: Bluett imagines, in the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, a bird singing (representing, as I take it, God’s word), but Adam and Eve heed not his song, and, taking the tree’s forbidden fruit, find themselves exiled. The bird weeps for the alienation of his two friends, and wings his way east of Eden, into the home of a young maiden, a daughter of Eve, who receives him, shelters him, an act that leads to restoration. Bluett uses some of the language of late medieval English folksong, such as “with a low, low, my love, my love” and “welaway.”

- “Two Turtledoves”

- “Three French Hens”

- “Four Calling Birds”: This poem is brilliant. In it the four matriarchs in Jesus’s genealogy speak to Mary, tenderly calling her “Child” and rejoicing in her “bringing forth our life’s tomorrow.” Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba—they’ve long awaited redemption, and now they’re at its threshold. Mary’s yes to God’s call “set[s] [their] dry bones stirring, thrumming / with a hope [they’d] hardly dared.” They inform her that her vocation will involve great suffering (as we know, she’ll experience the brutal death of her son)—but her willingness to give up her son to the cross, to endure that rupture, will mean new life for the world.

- “Five Gold Rings”

- “Six Geese a-Laying”: Picking up the Isaianic language of the wilderness being made glad, the poetic speaker sings an eschatological vision of flocks coming home to “the orchard of the rood” (rood = cross) to lay and hatch eggs in nests once empty, now brimming with life.

- “Seven Swans a-Swimming”

I eagerly await the remaining five poems!

Update, 12/23/25:

- “Eight Maids a-Milking”

- “Nine Ladies Dancing”

- “Ten Lords a-Leaping”

- “Eleven Pipers Piping”

- “Twelve Drummers Drumming”

+++

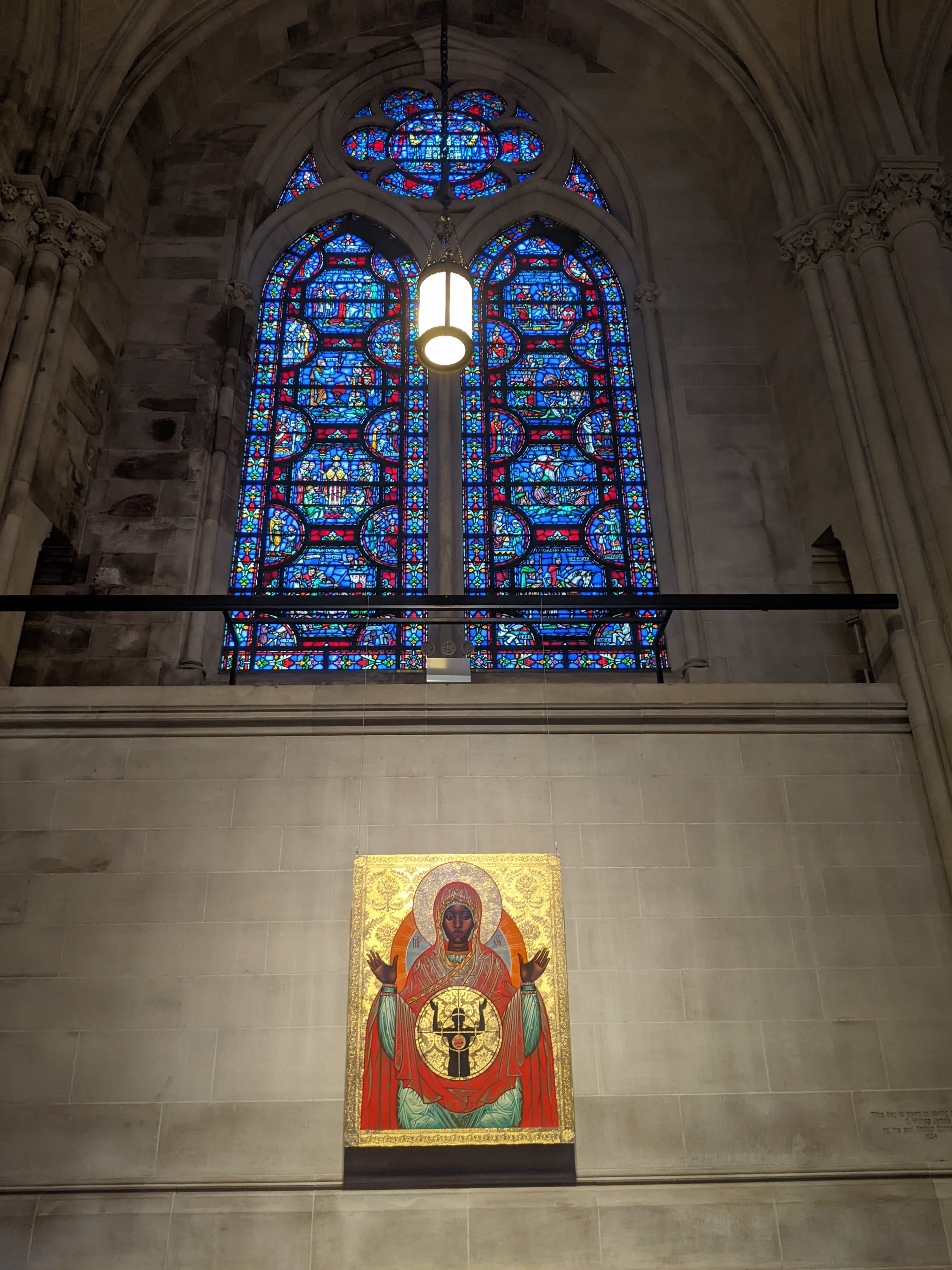

SUBSTACK SERIES: “Art + Advent 2025” by Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt: The art historian Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt [previously], author of Redeeming Vision and the Loving Look Substack, is one of my favorite writers. This Advent she is writing a weekly series of art reflections centered on the themes of hope, peace, joy, and love.

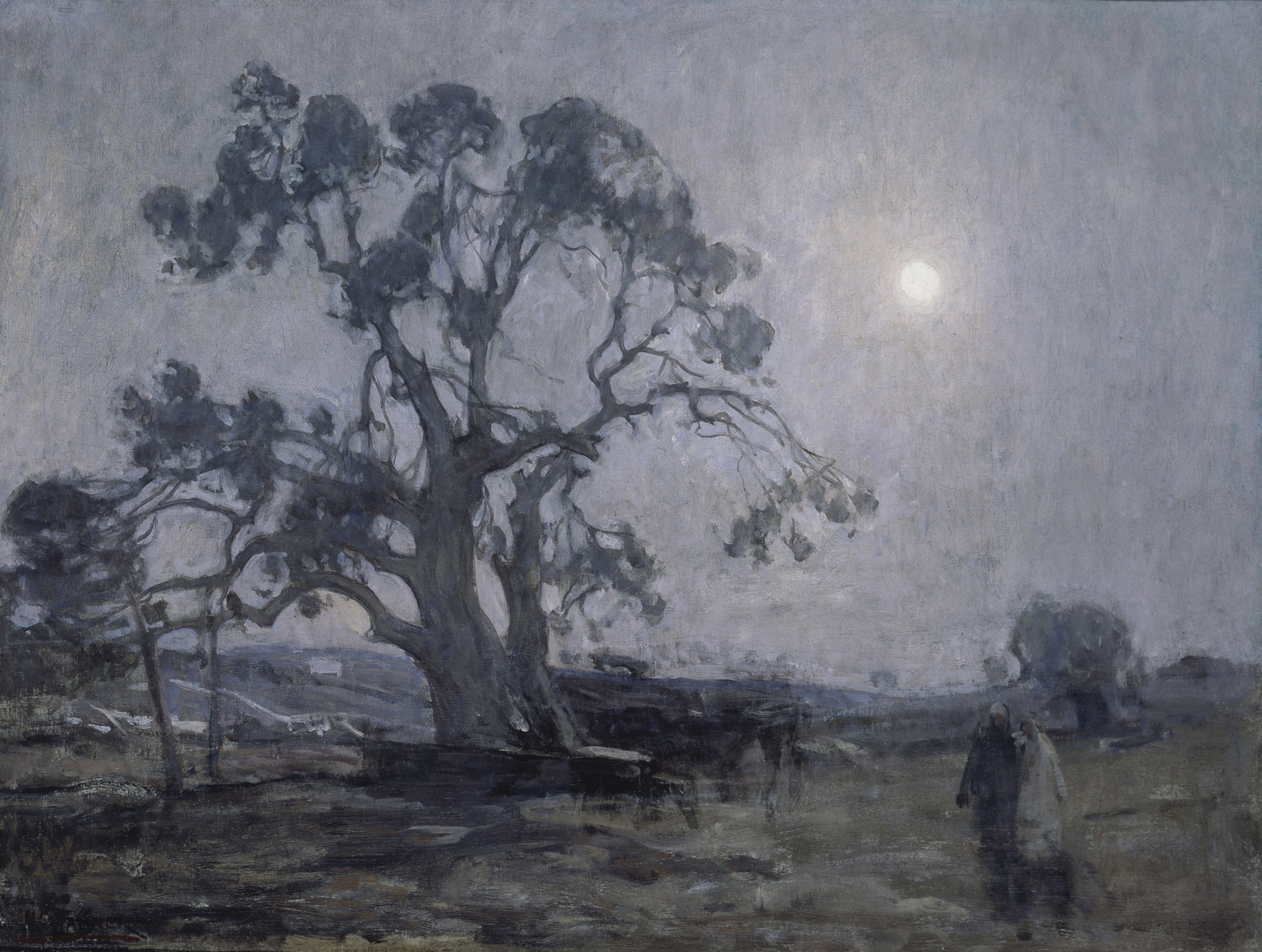

>> “Week 1 // Hope: Abraham’s Oak and Sarah’s Laughter”: Looking at Henry Ossawa Tanner’s painting Abraham’s Oak, Weichbrodt writes about shadowy promise. She also considers, with reference to an early Byzantine mosaic of the Hospitality of Abraham, how to hope again after being wounded, as Sarah did, is a vulnerable thing. “As Advent begins, I find myself peering into a Tanner-like mist, seeing the dim outline of longed-for goodness taking shape in the distance. Sometimes I’m full of hope, but I’m also, like Sarah, sometimes full of armored laughter.”

>> “Week 2 // Peace: A Stitch Pulling Tight”: “How do we do repair work in a fraying world with our own, fraying selves? What thread can stitch together all these gaping wounds?” Weichbrodt asks. She looks at Mary Weatherford’s monumental painting Gloria (new to me!), finding in the hot coral neon light blazing across the canvas resonance with Renaissance paintings of the Annunciation, which portray the Light of the World as the stitch that mends the tear between God and humanity.

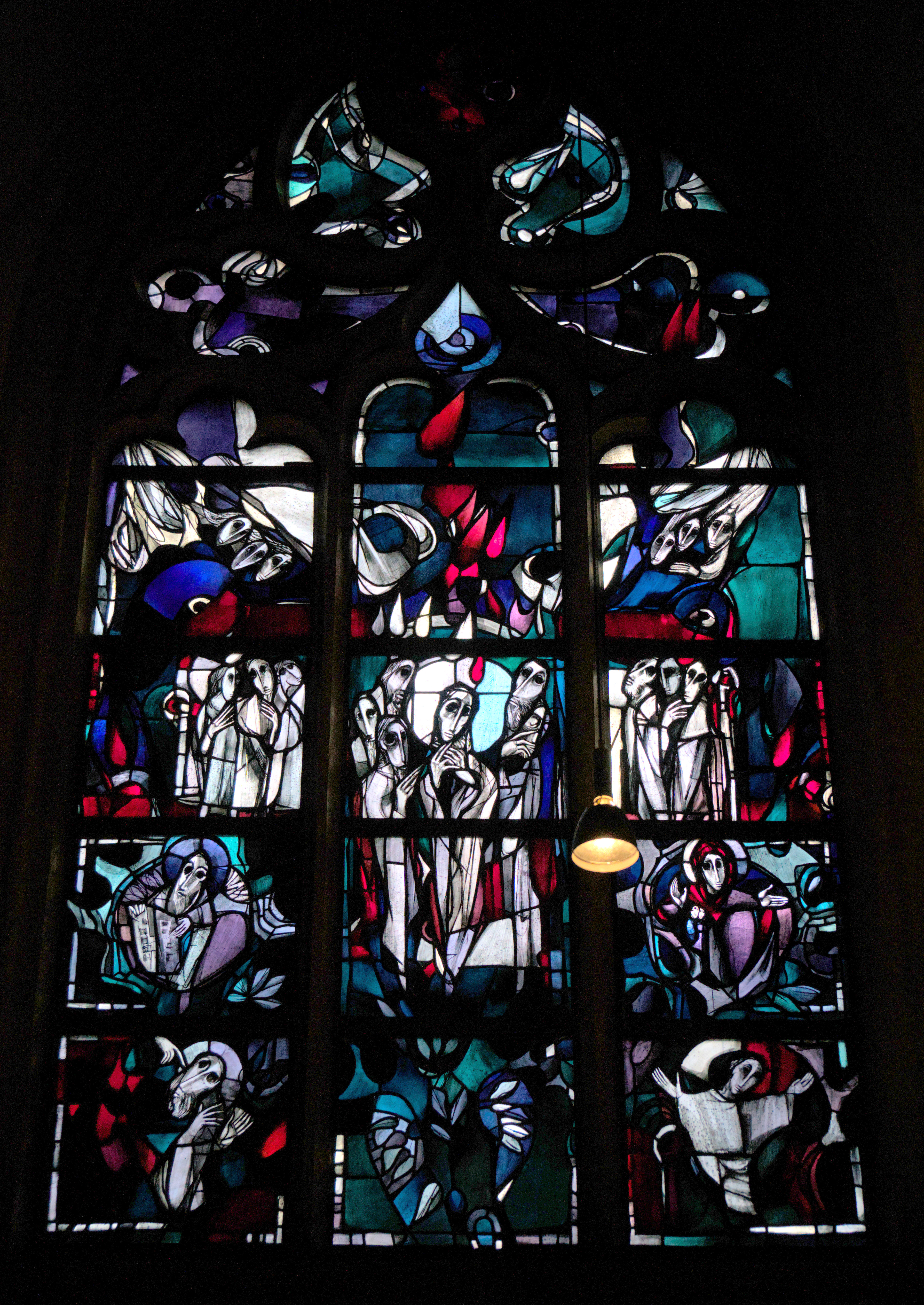

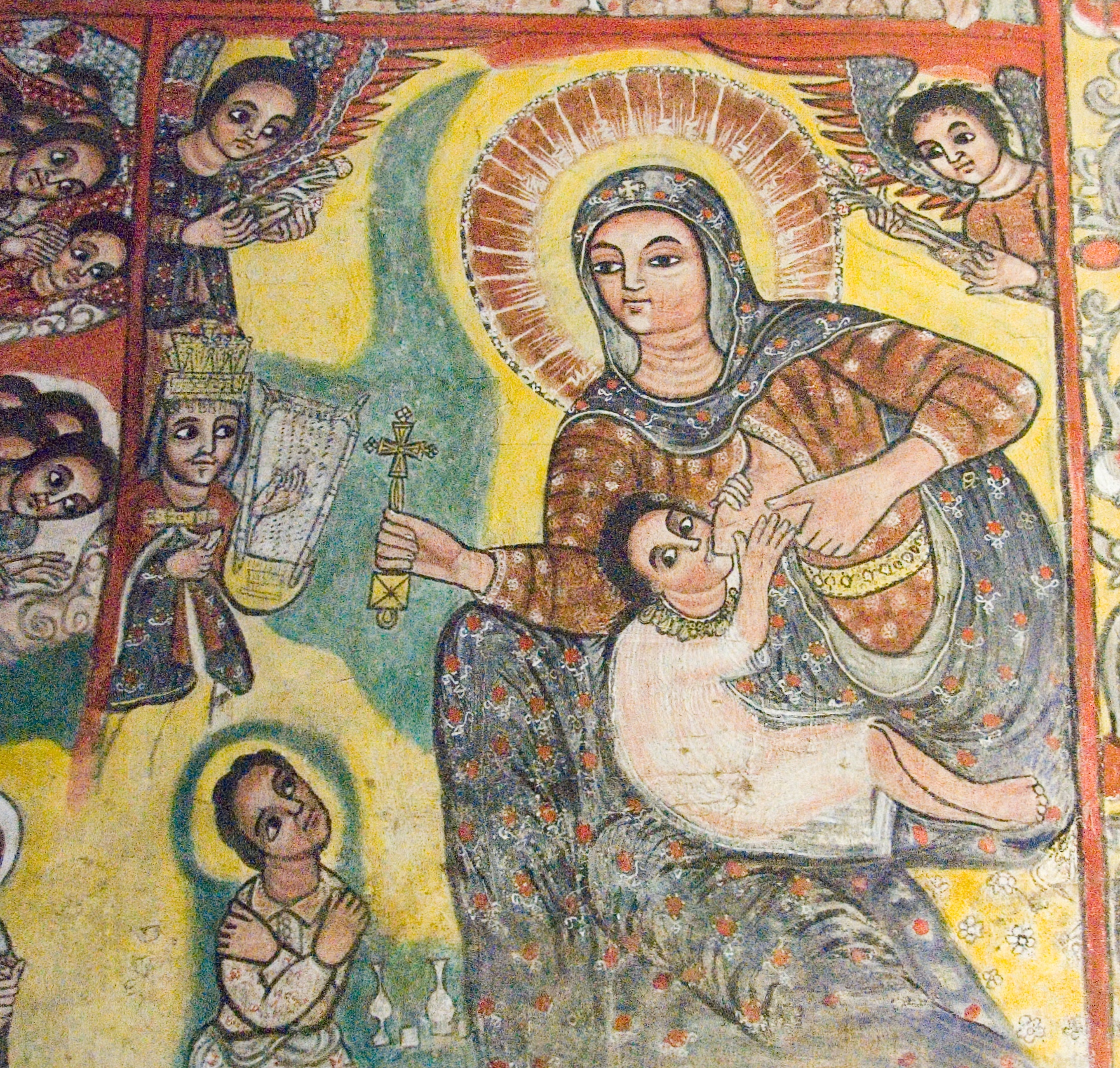

>> “Week 3 // Joy: Far as the Curse Is Found”: In this post, Weichbrodt explores nine Visitation paintings and one extraordinary embroidery. “Every time I see [a Visitation artwork],” Weichbrodt writes, “I encounter joy. It’s not that Mary and Elizabeth are always smiling. Often, their expressions are quite serious. But joy—deep, sustained, sustaining joy—circulates between them like an electrical current.” Justice, threshold, and fecundity are among the supplementary themes touched on.

Weichbrodt’s final Advent 2025 post, on love, will be published this Saturday. Weichbrodt’s final Advent 2025 post, on love, will be published this Saturday. (Update, 12/20/25: Week 4’s post, “Love In Between,” is now published. It centers on Vincent van Gogh’s painting Almond Blossoms, a gift for his newborn nephew, but also spends time with a Nativity mosaic by Pietro Cavallini and a Nativity painting by Gerard David.)

+++

SONGS:

Here are four newly released Christmas songs of note: two originals, one lyrical adaptation of a classic, and a new arrangement.

>> “War on Christmas” by Seryn: Seryn’s new album is titled War on Christmas. Here’s the title track:

The refrain is:

There is a war on Christmas

But it’s not the one you think

It’s in the news, it’s out of mind

It happens overseas

Cause as we sing the hymns and songs

With families by our sides

There is a war on Christmas

Someone’s fighting to survive

“War on Christmas” is a phrase some Christian conservatives in the US use to express their feeling of having their faith traditions attacked by the sinister forces of pluralism when people or signage greet them with a generic “Happy Holidays” instead of “Merry Christmas.” I roll my eyes big-time when I hear people complain about this, because it’s ridiculous for any American to assert that they are impeded from or ostracized for celebrating Christmas in this country, or to take offense that a stranger does not automatically assume their particular religious affiliation.

Seryn’s song affirms that yes, there is a war on Christmas—only it’s a war not against personal religious freedoms in America but against peace, love, and the other values Christ came to teach and embody. When humans wage literal wars with literal weapons, killing and maiming each other and inducing mass terror—that’s an assault against Christ’s mass, with its message of welcome and reconciliation. So, too, when we perpetuate hate, whether on personal, national, or global scales. As another Christmas song puts it, “Hate is strong and mocks the song of ‘Peace on earth, goodwill to men.’”

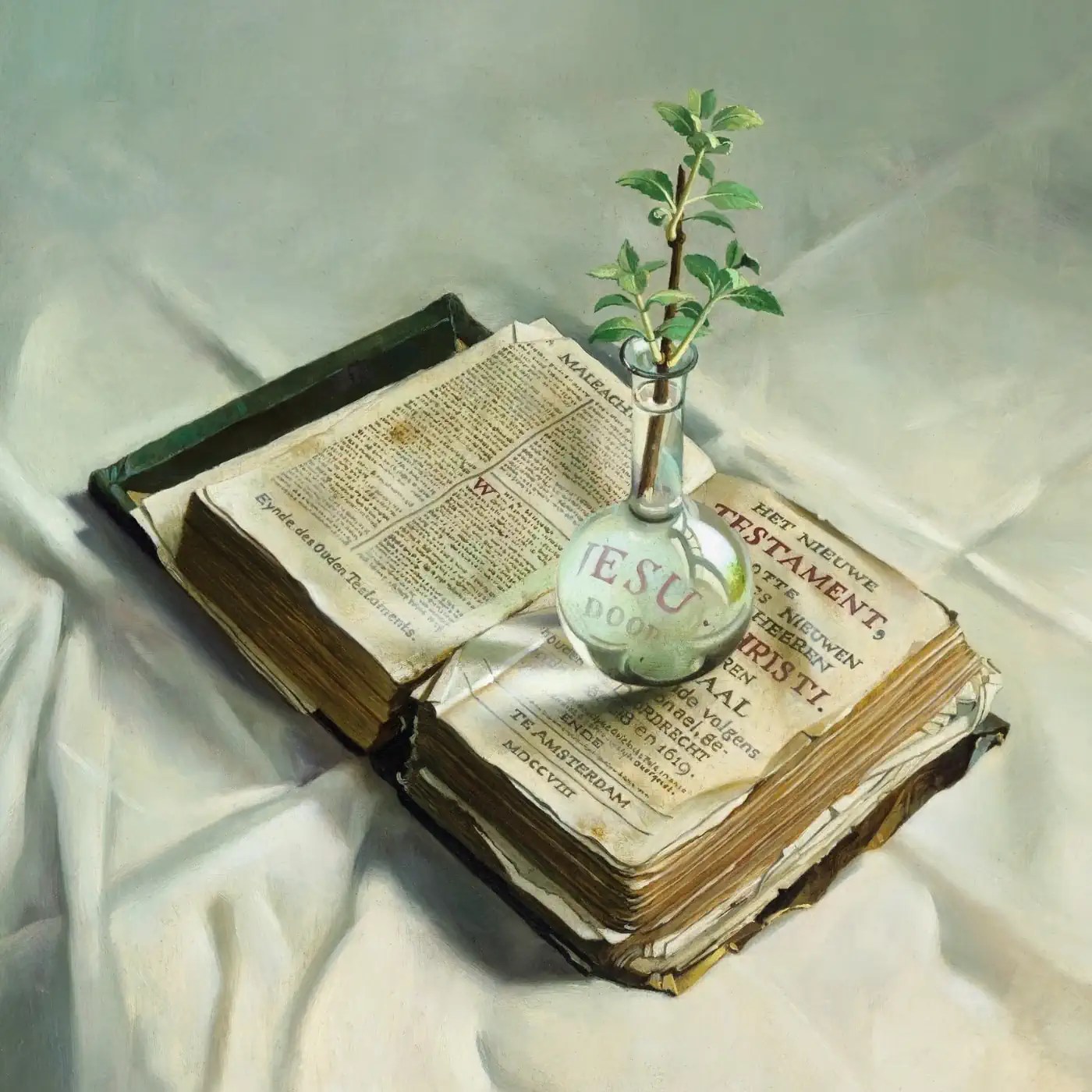

>> “O New Commingling! O Strange Conjunction!” by the Anachronists: The lyrics to this new song by the Anachronists [previously]—Corey Janz, Andrés Pérez González, and Jonathan Lipps—are a paraphrase from the sermon “On the Theophany, or Birthday of Christ” by Gregory of Nazianzus (ca. 329–390), one of the most influential and poetic theologians of the early church. Gregory delivered the sermon, labeled “Oration 38” in the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers series, at Christmastime in 380 in Constantinople, where he served as bishop. In section 13, the Anachronists’ source for the song, he expresses awe at the beautiful mystery of the Incarnation. Below is an excerpt from the public-domain NPNF translation.

The Word of God Himself—Who is before all worlds, the Invisible, the Incomprehensible, the Bodiless, Beginning of Beginning, the Light of Light, the Source of Life and Immortality, the Image of the Archetypal Beauty, the immovable Seal, the unchangeable Image, the Father’s Definition and Word—came to His own Image, and took on Him flesh for the sake of our flesh, and mingled Himself with an intelligent soul for my soul’s sake, purifying like by like; and in all points except sin was made man. . . . O new commingling; O strange conjunction; the Self-Existent comes into being, the Uncreate is created, That which cannot be contained is contained. . . . He Who gives riches becomes poor, for He assumes the poverty of my flesh, that I may assume the richness of His Godhead. He that is full empties Himself, for He empties Himself of His glory for a short while, that I may have a share in His fullness. What is the riches of His goodness? What is this mystery that is around me? I had a share in the image; I did not keep it; He partakes of my flesh that He may both save the image and make the flesh immortal. He communicates a second Communion far more marvelous than the first.

(Related post: Andy Bast sets to music a Nativity hymn by St. Ephrem)

>> “Away in a Manger (Then to Calvary)” by Sarah Sparks: Singer-songwriter Sarah Sparks [previously] released a new EP, Christmas Hymns, last month, comprising five classic carols, including one with revised lyrics that further draw out the significance of the Incarnation. I’m a big fan of Sparks’s voice and her no-frills acoustic style.

Away in the manger

No crib for a bed

The great King of Heaven

Does lay down his head

The stars he created

Look down where he lay

The little Lord Jesus

Asleep on the hayAnd there in the manger

The Maker of earth

In riches and glory?

No, born in the dirt

With oxen and cattle

With shepherds and sheep

No stranger to weakness

He loves even meAnd there in the manger

Is our Servant-King

He sits with the lowly

He washes their feet

Away in the manger

Then to Calvary

His birth, life, and death

And his raising for meAnd there in the manger

Is my greatest friend

His mercy, his patience

His grace know no end

Be near me, Lord Jesus

For all of my days

In life and in death

Till we meet face to face

>> “Angels We Have Heard on High” by the Petersens: Last Friday the Petersens [previously] released a music video—shot at Wonderland Tree Farm in Pea Ridge, Arkansas—debuting their new bluegrass arrangement of one of my favorite Christmas carols. Banjo, mandolin, fiddle, acoustic guitar, dobro, upright bass—I love the instrumentation of the bluegrass genre and what it adds here, and the Petersens are consummate performers.