And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying,

“See, the home of God is among mortals.

He will dwell with them;

they will be his peoples,

and God himself will be with them;

he will wipe every tear from their eyes.

Death will be no more;

mourning and crying and pain will be no more,

for the first things have passed away.”—Revelation 21:3–4

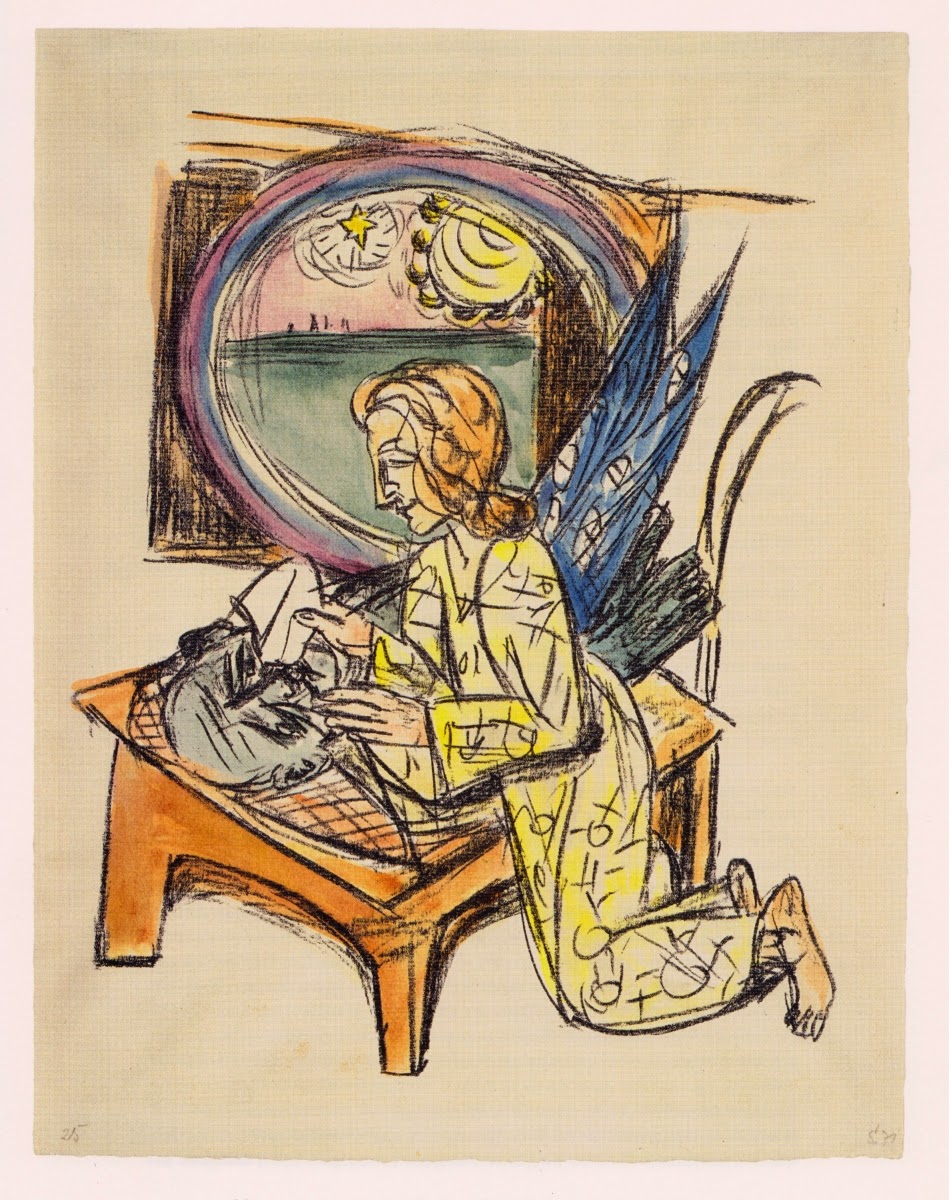

LOOK: God will wipe away every tear by Max Beckmann

The German expressionist artist Max Beckmann created this poignant lithograph in 1941–42 while living in exile in Amsterdam, having been labeled a “degenerate artist” by the Nazi Party and stigmatized as “un-German.” It’s one of a series of twenty-seven lithographs he made on the book of Revelation. Titled Apokalypse, the series was commissioned by Georg Hartmann, owner of the Bauersche Gießerei (Bauer type foundry) in Frankfurt am Main, who privately printed it as a bound volume in 1943 in an edition of twenty-four. God will wipe away every tear is page 71. I’ve pictured here the edition in the collection of the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, but there’s another one (with different hand-coloring) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

I learned about this piece from the fantastic book Picturing the Apocalypse: The Book of Revelation in the Arts over Two Millennia by Natasha O’Hear and her father, Anthony O’Hear. Natasha describes and comments on it:

A winged figure is depicted by Beckmann dressed in a golden robe wiping away the tears from a squat, human figure lying on a table (who may be intended to be Beckmann himself). Through a circular window, which resembles a port hole and which is decorated with the colours of the rainbow, lies what one presumes to be the new Heaven and the new Earth (Rev. 21.1), here represented as just the river (sea?) of life and not a city. The fact that one has to gaze through the rainbow port hole to glimpse the New Jerusalem is fascinating and reminds one of Memling’s Apocalypse altarpiece of 1474–9, which depicts the heavenly throne room as existing in a circular rainbow resembling an eyeball. It has been argued that this visualization implies that the heavenly throne room (described in Rev. 4.3 as being enclosed in a rainbow) is akin to the all-seeing divine eye. Thus, in this image, if it is Memling who is being evoked here, the viewer, like John, is in the privileged position of seeing the future through the divine eye, as it were.

However, the theological intrigue plays second string to the central image, which would surely have resonated with viewers as somewhat strange, shocking even, in the 1940s. The concept of visualizing God/Christ himself wiping the tears from human eyes is not without artistic precedent, but it is rare. Giovanni di Paolo’s illustrated fifteenth-century antiphonal depicts ‘God wiping away the tears of the faithful,’ for example. [See also this historiated initial in the fourteenth-century Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas.] However, this is such an intimate image, and the divine figure (perhaps God/Christ or perhaps an angel) so human (apart from the wings, of course), that one cannot help being affected by the image. This New Jerusalem is a place of consolation built on relationships and not monumental landscapes. (231–32)

LISTEN: “God shall wipe away all tears,” from movement 13 of The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace by Karl Jenkins, 2000 | Performed by the Hjorthagens kammarkör (Hjorthagen Chamber Choir), dir. Karin Oldgren, 2021

God shall wipe away all tears

And there shall be no more death

Neither sorrow nor crying

Neither shall there be any more painPraise the Lord

Praise the Lord

Praise the Lord

This glorious piece of music is from the end of the final movement (“Better Is Peace”) of The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace by the Welsh composer and multi-instrumentalist Sir Karl Jenkins. Written for SATB choir, SATB soloists, muezzin, and a full orchestra with an enormous percussion section, the work was commissioned by the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds, England, to commemorate the new millennium. Jenkins dedicated it to the victims of the Kosovo War between the Serbians and the ethnic Albanians, which lasted from February 1998 to June 1999.

It has been performed around the world over three thousand times and is one of Britian’s favorite pieces of contemporary classical music.

One of the primary genres in the Western choral tradition is the mass, which sets to music the five unchanging sections of the Roman Catholic liturgy: the Kyrie (“Lord, have mercy”), Gloria (“Glory to God in the highest”), Credo (“I believe”), Sanctus (“Holy, holy, holy”), and Agnus Dei (“Lamb of God”). Bach’s Mass in B minor and Mozart’s Requiem in D minor are among two of the most famous. Composer’s masses were originally sung in the church’s corporate worship, but now they’re mostly confined to concert settings and are often adapted—supplemented with other texts, and sometimes one or more of the traditional sections is eliminated.

Karl Jenkins’s The Armed Man, named after the fifteenth-century French folk song “L’homme armé,” which opens the mass, comprises thirteen movements. Jenkins omits the Gloria and Credo but, in addition to the Kyrie, Sanctus (and Benedictus), and Agnus Dei, includes other religious texts and secular ones too: the Adhan (Islamic call to prayer); Psalms 56:1 and 59:2; poems or poetic extracts by Rudyard Kipling, John Dryden, Horace, Toge Sankichi (who survived the bombing of Hiroshima but died of radiation-induced cancer), Guy Wilson, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson; a passage from the ancient Hindu epic the Mahabharata and from Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur; and Revelation 21:4.

For a movement-by-movement discussion of the mass, including all the lyrics, see the Choral Singer’s Companion entry by the musicologist Honey Meconi. And here you can listen to the work in full, as performed in 2018 in Berlin by a choir of two thousand people from thirty countries to mark the centennial of the end of the First World War:

The “God shall wipe away all tears” finale is markedly different from the two sections that precede it within the same movement. Movement 13 starts (at 58:26 of the Berlin video) with a vigorous and cheerful return of the “L’homme armé” melody, this time sung with a line from Mallory—voiced, in Mallory’s version of the Arthurian legends, by Lancelot and Guinevere:

Better is peace than always war,

And better is peace than evermore war,

And better and better is peace,

Better is peace than always war.

The melody’s original lyrics then return:

The armed man must be feared.

Everywhere it has been proclaimed

That each man should arm himself

With an iron coat of mail.

But then the sprightly woodwinds play a Celtic dance–like interlude, leading into the choir’s “Ring, ring, ring, ring!” and a setting, with lush orchestral backing, of Tennyson’s “Ring Out, Wild Bells.” This section is joyous and triumphant, and listeners might expect that final, emphatic “Ring!” to be the closer.

But it’s not.

The final section, a sort of coda, is quiet, slow, unaccompanied—no brass fanfare, no frolicsome woodwinds, no driving percussion, just human voices singing at a largo tempo a snippet from John the Revelator’s eschatological vision of a world without death, crying, and pain, having been healed by God for all eternity.