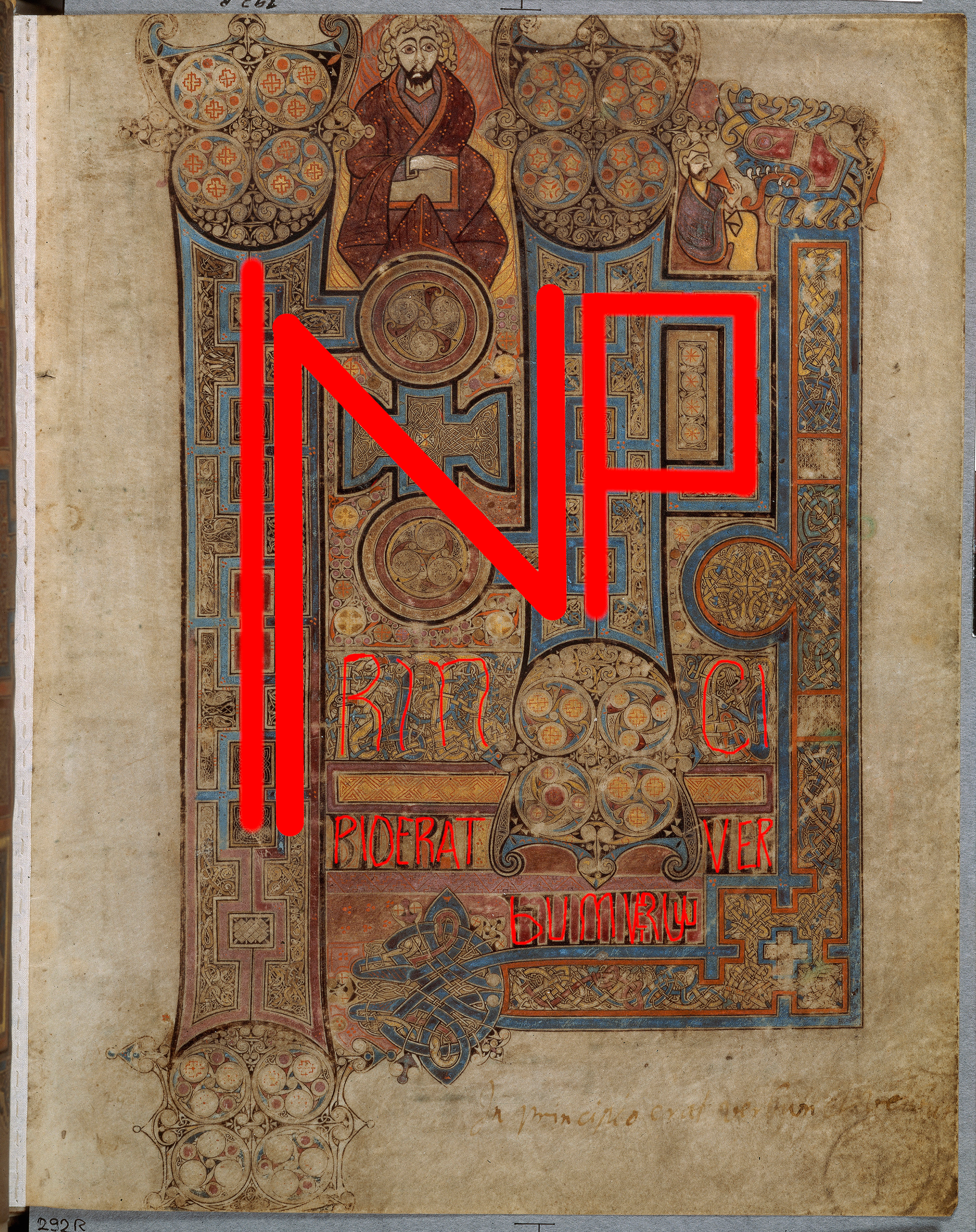

LOOK: Incipit to the Gospel of John from the Book of Kells

Made by Celtic monks in a Columban monastery around the year 800, the Book of Kells—an illuminated Gospel book named after the monastery of Kells in County Meath, Ireland, where it spent eight centuries—is one of the most beautiful manuscripts ever created. Pictured here is the lavishly decorated opening page of the Gospel of John, which bears the words “In p/rinci/pio erat ver/bum [et] ver[b]um” (“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word . . .”). The passage continues on the following page.

Bernard Meehan, the former head of research collections and keeper of manuscripts at Trinity College Dublin, describes the lettering on folio 292r:

The letters IN P, filled with interlacing snakes, crosses and abstract ornament, dominate the composition. Snakes form the letters RIN and C, with C taking the form of a harp, played by the man who forms the letter I. The urge of the artist to decorate has taken precedence over legibility, to the extent that the letters ET and B are missing from the last line. [1]

Because some of the letters are difficult to discern, I’ve done my best to trace them in red in this graphic:

The text unfolds in four rows. The column on the left forms the I and doubles as the left stem of the N. The diagonal stroke of the N passes through the cross-shape, and its right stem is formed by another blue column, which also doubles as the stem of the P.

The following R, I, N, and C are beige and blue serpentine figures, tangled together, the latter shaped like a harp and being “played” by a seated man whose torso forms an I.

The remaining text is organized in two rows and is black. As Meehan mentioned, the artist-monk unintentionally omitted the ET and B in “et verbum.” And the final M is upside down, an artistic variation.

(Related post: “The Book of Kells,” a poem by Howard Nemerov)

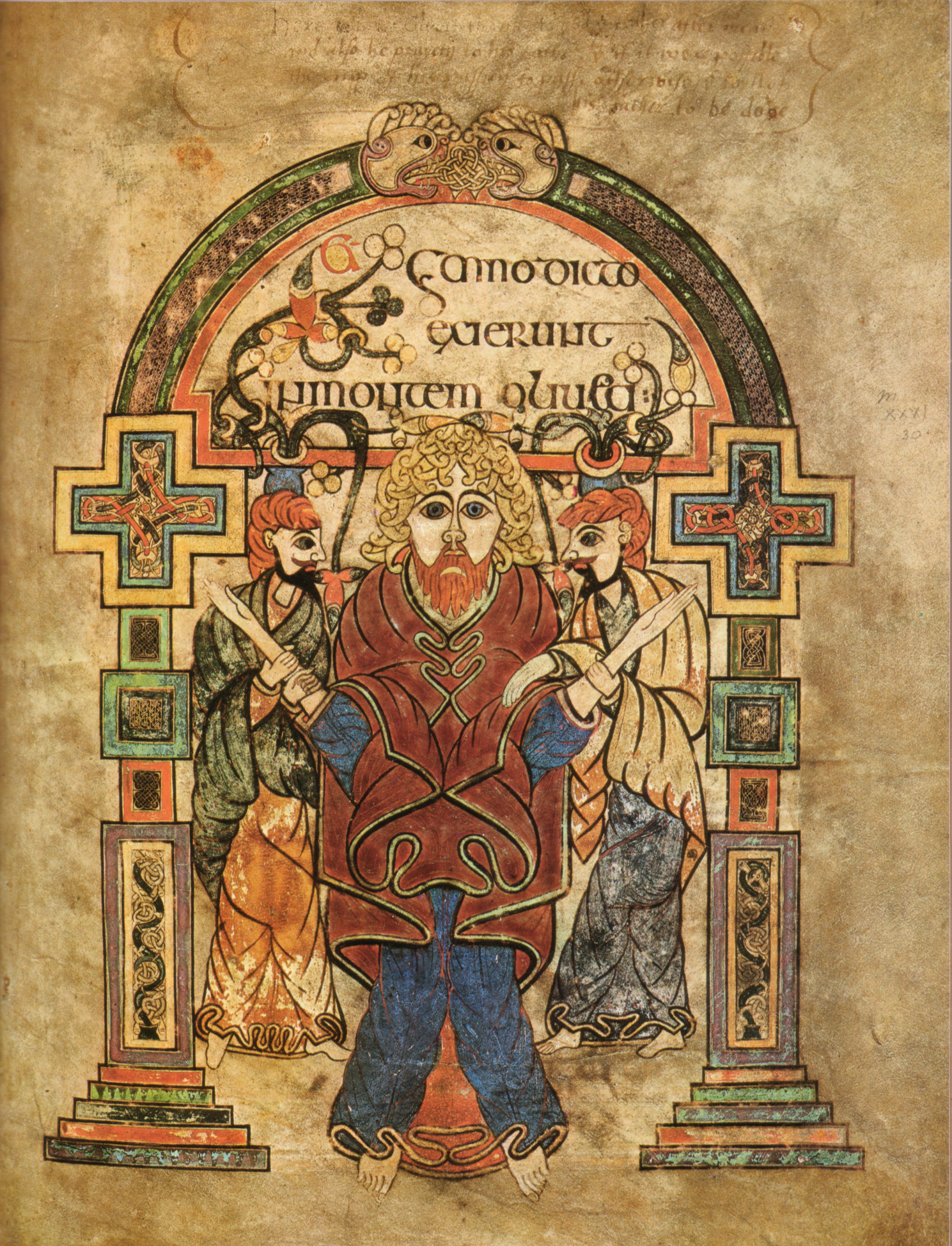

Scholars disagree on who the curly-haired figure at the top is, holding a book: some suppose it’s John the Evangelist, the author of the fourth Gospel, while others think it’s Christ the Logos. I’m in the latter camp. Christ is often shown in art sitting on a throne holding a book, representing the gospel—as on folio 32v of this very manuscript. And a full-page portrait of John already appears on the opposite page, folio 291v; granted, the iconography is similar, but it would be an unusual choice to repeat a person in the same pose on a single page spread. Also, as art historian Heather Pulliam points out, the yellow and red striations that encompass the figure resemble flame—a “throne of light,” writes Françoise Henry—an attribute more befitting of the figure of Christ than of John. [2]

The identity of the smaller figure on the right who’s drinking from a red chalice is also debated. Again, it could be either John or Christ. According to an apocryphal legend that first appeared in the second-century Acts of John and that was popularized in the thirteenth-century Golden Legend, a pagan priest challenged John to drink a cup of poisoned wine to test whether his God was truly powerful enough to protect him. John blessed the cup, downed the wine, and suffered no harm. That’s why in art one of John’s attributes is a chalice with a serpent in it, representing the poison rising out and the triumph of Christian faith.

On the other hand, the drinking figure may be Christ drinking the cup of suffering (John 18:11). The monstrous head to the right supports either interpretation—it could be Satan tormenting Christ in Gethsemane, or in John’s case, the threat of death by poison, or the evil intent of the pagan priest who sought to discredit him.

Additional possibilities have also been posited. Małgorzata Krasnodębska-D’Aughton argues that the man is meant to be a generic Christian partaking of the Eucharist, [3] whereas Pulliam suggests that the cup represents not the blood of Christ but “the chalice of wisdom received from the breast of Christ.” [4] She cites Augustine’s first tractate on the Gospel of John:

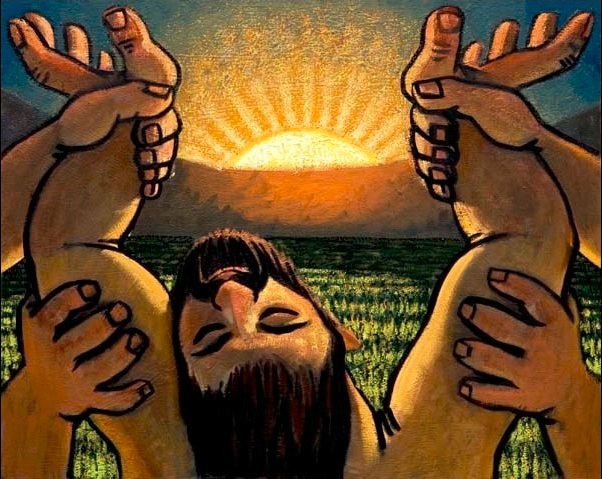

Thence John, who said these things, received them, brothers, he who lay on the Lord’s breast, and from the breast of the Lord drank in what he might give us to drink. But he gave us words; you ought then to receive understanding from the source, from that which he drank who gave to you; so that you may lift up your eyes to the mountains from where shall come your aid, so that from there you may receive, as it were, the cup, that is, the word, given you to drink; and yet, since your help is from the Lord, who made heaven and earth, you may fill your breast, from the source. [5]

In Pulliam’s interpretation, the man imbibes the words of God—that is, scripture—providing a model for us to emulate.

Click here to digitally browse the Book of Kells in full.

Notes:

- Bernard Meehan, The Book of Kells: An Illustrated Introduction to the Manuscript in Trinity College Dublin (Thames & Hudson, 1994, 2008), 34.

- Heather Pulliam, Word and Image in the Book of Kells (Four Courts Press, 2006), 180–83; cf. Françoise Henry, The Book of Kells: Reproductions from the Manuscript in Trinity College, Dublin (Thames & Hudson, 1974).

- Małgorzata Krasnodębska-D’Aughton, “Decoration of the In principio initials in early Insular manuscripts: Christ as a visible image of the invisible God,” Word and Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry 18, no. 3 (Fall 2002): 117.

- Pulliam, Word and Image, 185.

- Augustine, In Joannis Evangelium 1.1, PL 35: 1382.

LISTEN: “The Word Was God” by Rosephanye Powell, 1996 | Performed by the University of Pretoria Camerata, dir. Michael Barrett, 2022

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

The same was in the beginning with God.

All things were made that have been made. Nothing was made he has not made.

While this choral anthem is not a Christmas song per se, it is a setting of John 1:1–3, the opening of the great prologue of the Incarnation. These first three verses are about Christ’s eternal being, his oneness with the Father, and his active role in creation. I can’t hear them without anticipating verse 14: “And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us . . .”

“The Word Was God” is by Dr. Rosephanye Powell (pronounced ro-SEH-fuh-nee) (born 1962), an African American composer, singer, professor, and researcher. One of her most popular and widely recorded works, it is full of rhythmic energy and drive. Read detailed notes by Powell here, where she explains her musical choices and their theological significance.