ARTWORK:

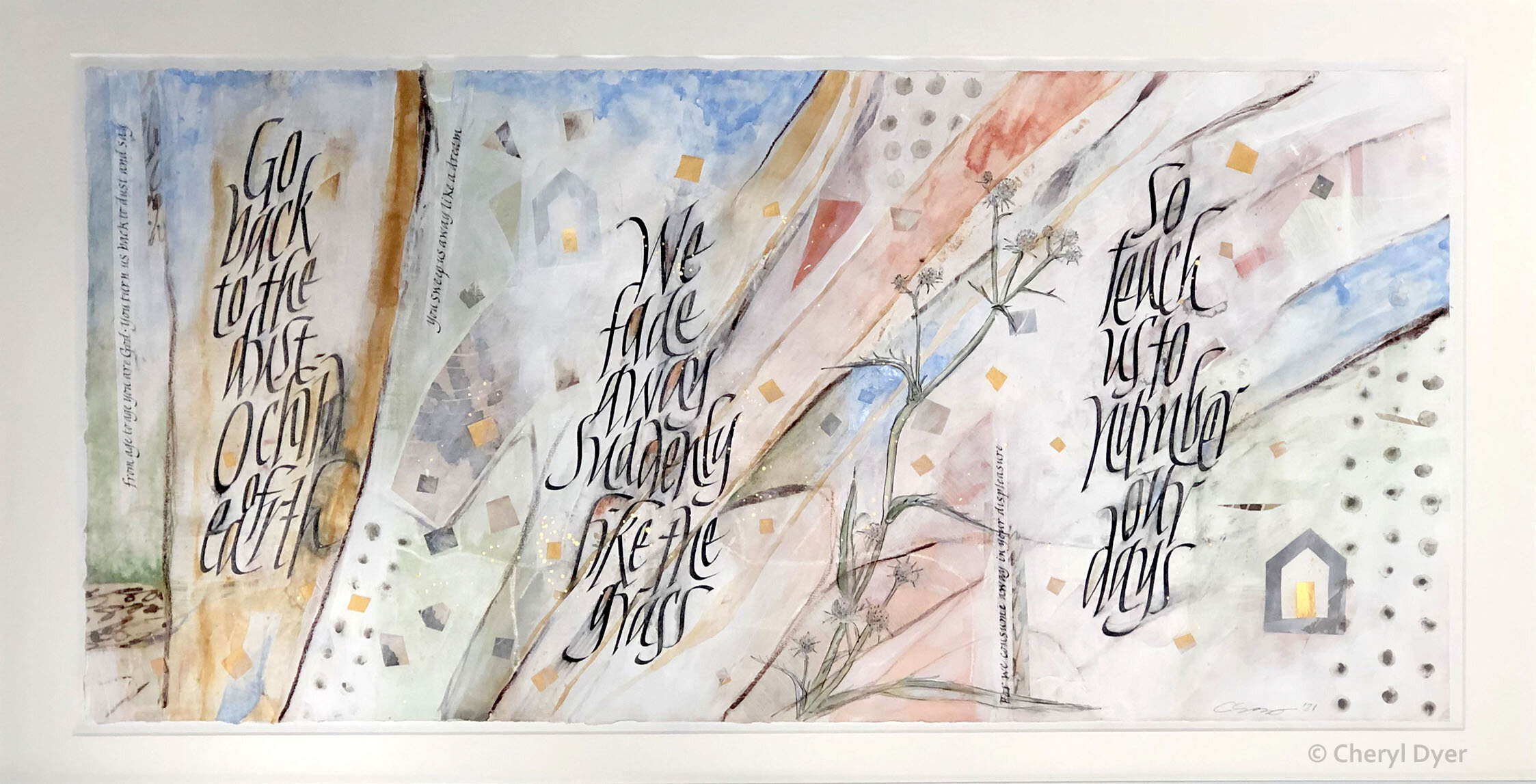

In this piece, lettering artist and calligrapher Cheryl Dyer of Omaha takes Psalm 90 (traditionally read on Ash Wednesday) as her subject, embellishing excerpts with watercolor and other media. Rattlesnake master is a perennial herb of the parsley family native to the tallgrass prairies of central and eastern North America.

+++

ARTICLE: “The Vindication and Blessing of Lent” by Rev. Dr. Michael Farley, Modern Reformation: I also sometimes receive pushback from others in my Reformed Christian circles for my observance of Lent. I appreciate Farley’s response to such concerns, explaining why he finds Lent—and the liturgical calendar as a whole—biblically, theologically, and practically compelling.

Note: If you’d like a new devotional booklet to work through this Lent that is broadly Reformed and that combines scripture readings, prayers, songs, art, and other elements, I recommend the Daily Prayer Project’s Living Prayer Periodical, which, full disclosure, I had a hand in producing. New for this year’s Lent edition, we’ve added a special page spread for each day of the Triduum: Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday. The cover image is of a thirteenth-century Armenian khachkar from the Monastery of Gosh and is one of eight featured artworks inside (three accompanied by written reflections, three by visio divina prompts). If you want to receive a copy by the start of Lent on Wednesday, order the digital version; otherwise, expect a few business days for shipping.

+++

SERMON: “Seasons of the Heart: Preparing for Lent” by James K. A. Smith: Last February, Jamie Smith preached on Ecclesiastes 3:1–8 and John 16:12–15 at his home church, Sherman Street Christian Reformed Church in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He talks about seasonality—how we creatures experience time in seasons, both personally and collectively—and encourages us to ask, “When am I?” Along the way he references Gustavo Gutiérrez, Rita Felski, and Bruce Springsteen. Below is a transcription of 23:42 onward, which I find so resonant. To receive the full force of this conclusion, listen to the whole sermon.

God has more to say to us in his word that we haven’t yet got. There is something in us, for us, in the word that we hear over and over and over again, and the way that we will get to the place of receiving it is precisely by giving ourselves over to the seasons in our lives and letting God do the work in us so that we get new ears, because we have new hearts. This is one of the reasons why . . . repetition is at the heart of the spiritual life. It’s exactly why we keep repeating the liturgical seasons over and over again. Why? Because every single one of us is a different person every time Advent arrives. Every single one of us has undergone something every single time Lent rolls around again.

And so as we’re preparing for Lent—this season of repentance, this season of encountering our mortality—again, I want to encourage us to ask: When am I? When are we? What am I going through? What season am I in? And then from that place, come to Lent with expectation. What does God want to say to me in the now that I find myself? What are you newly ready for because of what you’ve come through? What can Jesus say to you this year that he couldn’t tell you last year?

So many of you are mourning. And the journey of Lent is really a journey of yearning for resurrection. But it passes through the valley of the shadow of death. Unapologetically. And the psalmists’ cries that you’re going to hear in Lent, maybe this year they’re going to give voice to a cry of your own that you didn’t have before. The experience of being bereft on Holy Saturday is going to hit some of you in a way it never has before this year. But maybe that also means that Easter dawns for you in a way it never has before.

Friends, maybe some of you feel, to go back to Ecclesiastes, that it’s a time to build and plant. Because you’ve come through the season of tearing down and uprooting. Maybe this Lent you feel like you’re finally in a place where you can be vulnerable to a God that you finally learned is compassionate, who loves you all the way down. This is a season to build, to plant.

Friends, maybe some of you feel like it’s the time of giving up and throwing away. There is a time for everything, the Teacher tells us. There’s a time to give up, there’s a time to throw away. But maybe it’s precisely what you need to let go of that has been blocking your ability to experience God’s incessant, steadfast, always love.

Whenever you are, whatever season you find yourself in, God has good news to share with you. That’s what we can rely on. No matter what season you’re in, the God who is eternal—the same yesterday, today, and forever—has always a word of good news, because he is always the God with us. He is always Emmanuel. And so this Lent and Eastertide, maybe this is the year you finally get God’s song. You finally hear the song of new life. And friends, I hope you hear that God is singing to you.

+++

VESPERS SERVICES AT CALVIN UNIVERSITY:

I’ve just returned from another inspiring Calvin Symposium on Worship, so grateful for all the gifts and wisdom that were shared. There’s much I could say, but one thing I discovered was how much I loved participating in Vespers, a short evening worship service consisting of scripture readings, prayers, and song (vesper in Latin simply means “evening”). It’s not something that’s regularly offered in my (Presbyterian) tradition, at least not near me. Here are three of the Vespers services that took place this week at Calvin, the latter two at which I was present:

>> Celtic Vespers: “Psalms of Healing and Hope for a Troubled World,” led by Kiran Young Wimberly and The McGraths: This service of psalms set to Celtic melodies was led by Kiran Young Wimberly and The McGraths (a Northern Ireland–based group that performs and records together), Mary Beth Mardis-LeCroy (violin), and Brian Hehn (piano). Since Ash Wednesday is this coming week, I’ll draw your attention especially to “From Dust We Came (Psalm 90)” (see timestamp 15:28), which uses the eighteenth-century Irish tune CASADH AN T’SÚGÁIN. Plus, another highlight for me: “Love and Mercy (Psalm 85),” set to the eighteenth-century Scottish tune LOVELY MOLLY (39:55)—I’ve added this to my Advent Playlist! For more info about the musicians and their work, see https://www.celticpsalms.com/.

>> Jazz Vespers: “Lament as Worship,” led by Ruth Naomi Floyd and her jazz quartet: Ruth Naomi Floyd is a phenomenal jazz vocalist, composer, and fine-art photographer. This liturgy that she crafted and presented is so moving. In her thoughtful selection of readings, Floyd brings a James Baldwin poem into conversation with Psalm 42:7–11 and even includes an amusing proverb from Chinua Achebe’s novel Arrow of God. She also adds a visual element: black-and-white photographic portraits she shot, which were displayed on slides during each segment (not all of them are featured in the video recording).

The musical performance, I hardly have words for. All I can say is, it was utterly engrossing. The expressiveness of Floyd’s voice is unmatched, carrying such pathos. I couldn’t pick a favorite song, but the opening spiritual, “Trouble So Hard” (11:37), hit me forcefully. The first verse talks about a mountaintop experience of spiritual ecstasy (“getting happy” refers to being filled with the Spirit), and that’s contrasted in the second verse with a descent into the valley of deep suffering and grief. The refrain asserts to God, seeking divine consolation, “Oh Lord, trouble so hard,” and then testifies that only God truly knows our troubles. Also take note of the concluding song, “Press On” (34:31), an original Floyd composition whose text is taken from the writings of Frederick Douglass, part of a larger body of work that has been recorded and will most likely be released by the end of this year, Floyd told me; see https://frederickdouglassjazzworks.com/.

The amazing instrumentalists are James Weidman (piano), Keith Loftis (saxophone), Matthew Parrish (bass), and Mark Prince (drums).

>> Choral Vespers: “Christ, Holy Vine, Christ, Living Tree,” led by David M. Cherwien and The Choral Scholars: Led by the West Michigan chamber ensemble The Choral Scholars and organist/pianist David Cherwien, this service centers on botanical imagery of Christ and his people—such a generative idea! I enjoyed singing Gerald Cartford’s responsorial setting of Psalm 141:1–4a and 8 (see timestamp 12:48); the refrain is “Let my prayer rise before you as incense; and the lifting of my hands as the evening sacrifice” (the plant connection is that incense is derived from fragrant gum resins, i.e., tree sap). Also, this was my first time hearing Elizabeth Poston’s “Jesus Christ, the Apple Tree” performed live (20:48), and the first time its words truly registered with me.

+++

PRAYER-POEM: “Marked by Ashes” by Walter Brueggemann: “. . . On this Wednesday, we submit our ashen way to you—you Easter parade of newness. Before the sun sets, take our Wednesday and Easter us, Easter us to joy and energy and courage and freedom . . .” This prayer by the Old Testament scholar and theologian Walter Brueggemann, from his book Prayers for a Privileged People (2008), is ostensibly for any ol’ Wednesday in the church year, but it could be used, with one small elision, for Ash Wednesday itself. I love how it reads Easter backward into Lent, recognizing that the fruits of Christ’s resurrection are borne all year round.

P.S. This year, Ash Wednesday falls on February 14, Valentine’s Day. It did too in 2018; read the poem by Luci Shaw that I published for that occasion.