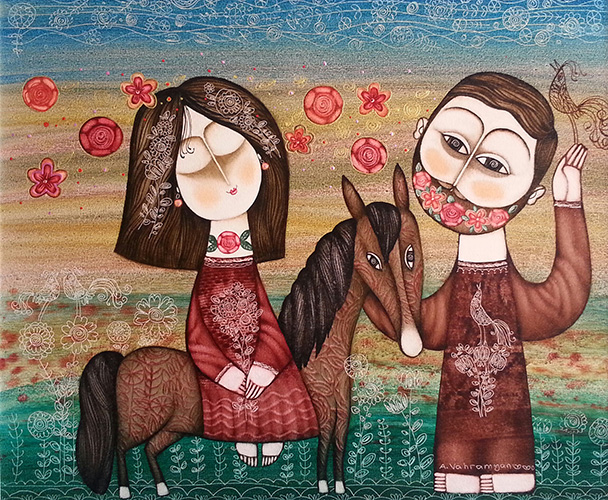

LOOK: Painting by Armen Vahramyan

LISTEN: “Joseph mon cher fidèle” (Joseph, My Dear Faithful One), traditional carol from the French West Indies | Performed by Robert Mavounza on Bakwa Nwel (2005)

Marie:

Joseph, mon cher fidèle,

Cherchons un logement,

Le temps presse et m’appelle

A mon accouchement.

Je sens le fruit de vie,

Ce cher enfant des cieux,

Qui d’une sainte vie,

Va paraître à nos yeux.

Joseph:

Dans ce triste équipage,

Marie allons chercher,

Par tout le voisinage,

Un endroit pour loger.

Ouvrez, voisin la porte,

Ayez compassion

D’une vierge qui porte

Votre rédemption.

Les voisins de Bethléem:

Dans toute la bourgade,

On craint trop les dangers,

Pour donner le passage

A des gens étrangers,

Au logis de la lune,

Vous n’avez qu’à loger,

Le chef de la commune

Pourrait bien se venger.

Marie:

Ah! Changez de langage,

Peuple de Bethléem,

Dieu vient chez nous pour gage,

Hélas! Ne craignez rien.

Mettez-vous aux fenêtres,

Ecoutez ce destin,

Votre Dieu, votre Maître,

Va sortir de mon sein.

Les voisins de Bethléem:

C’est quelque stratagème

On peut faire la nuit,

Quelque tour de bohème,

Quand le soleil ne luit.

Sans voir ni clair, ni lune,

Les méchants font leurs coups,

Gardez votre infortune,

Passants, retirez-vous!

Joseph:

O ciel quelle aventure,

Sans trouver un endroit,

Dans ce temps de froidure,

Pour coucher sous le toit.

Créature barbare,

Ta rigueur te fait tort,

Ton coeur déjà s’égare

En ne plaignant mon sort.

Marie:

Puisque la nuit s’approche

Pour nous mettre à couvert,

Ah! Fuyons ce reproche,

J’aperçois au désert

Une vieille cabane,

Allons mon cher époux,

J’entends le boeuf et l’âne

Qui nous seront plus doux.

Joseph:

Que ferons-nous Marie,

Dans un si méchant lieu,

Pour conserver la vie

Au petit Enfant-Dieu?

Le monarque des anges

Naîtra dans un bercail

Sans feu, sans drap, sans langes

Et sans palais royal.

Marie:

Le ciel, je vous assure,

Pourrait nous secourir,

Je porte bon augure,

Sans crainte de périr.

J’entends déjà les anges

Qui font d’un ton joyeux,

Retentir les louanges,

Sous la voûte des Cieux.

Joseph:

Trop heureuse retraite,

Plus noble mille fois,

Plus riche et plus parfaite

Que le louvre des rois!

Logeant un Dieu fait homme,

L’auteur du paradis,

Que le prophète nomme

Le Messie promis.

Marie:

J’entends le coq qui chante,

C’est l’heure de minuit,

O ciel! Un dieu m’enchante,

Je vois mon sacré fruit,

Je pâme, je meurs d’aise,

Venez mon bien-aimé!

Que je vous serre et baise!

Mon coeur est tout charmé.

Joseph:

Vers Joseph votre père

Nourrisson plein d’appas,

Du sein de votre mère

Venez entre mes bras!

Ah! Que je vous caresse,

Victime des pêcheurs,

Mêlons, mêlons sans cesse,

Nos soupirs et nos pleurs.

Mary:

Joseph, my dear faithful one,

Let us search for lodging;

Time is pressing and calling me

To give birth.

I feel the fruit of life,

This dear child from heaven

Who, with a holy life,

Will appear before our eyes.

Joseph:

In this sad predicament,

Let us search, Mary,

Throughout the neighborhood

For a place to stay.

Open the door, neighbor;

Have compassion

For a virgin who carries

Your redemption.

The people of Bethlehem:

Throughout the town,

There is too much fear of danger

To offer shelter

To strangers.

Under the moonlight

Is where you can go lodge;

The town’s ruler

Might seek revenge [on us].

Mary:

Ah! Change your words,

People of Bethlehem;

God comes to us as a pledge.

Alas! Do not fear.

Stand by your windows,

Listen to this destiny:

Your God, your Master,

Will come forth from within me.

The people of Bethlehem:

It’s some kind of ploy,

Which they can work at night,

Some vagabond trick,

When the sun isn’t shining.

Without seeing clearly, without the moon,

The wicked carry out their deeds.

Keep your misfortune;

Passersby, be gone!

Joseph:

Oh heavens, what a hardship,

To not find a place

In this cold weather,

A roof to sleep under.

Barbaric creatures,

Your harshness does you wrong;

Your heart is gone astray,

Not sympathizing with my fate.

Mary:

As the night draws near

To wrap us with its cover,

Ah! let us escape this reproach.

I see in the desert

An old shed.

Come, my dear husband:

I hear the ox and the donkey

Who will be kinder to us.

Joseph:

What shall we do, Mary,

In such a wretched place,

To preserve the life

Of the little Child of God?

The king of angels

Will be born in a manger,

Without fire, without sheets,

And without a royal palace.

Mary:

Heaven, I assure you,

Will come to our aid;

I carry good omens,

And no fear of perishing.

I already hear the angels,

In a joyful tone,

Resounding with praises

Under the vault of heaven.

Joseph:

What a blessed retreat,

A thousand times nobler,

Richer, and more perfect

Than the abode of kings!

Lodging a God made man,

The author of paradise,

Whom the prophet calls

The promised Messiah.

Mary:

I hear the rooster singing;

It’s the hour of midnight.

Oh heavens! A god enchants me.

I see my sacred fruit;

I faint, and am overcome with joy.

Come, my beloved [son]!

Let me hold you and kiss you!

My heart is completely charmed.

Joseph:

Come to Joseph, your father,

Darling boy;

Come into my arms

From your mother’s breast!

Ah! Let me caress you,

Sacrifice for sinners!

Let’s mingle, let’s mingle without ceasing,

Our sighs and our tears.

* This English translation by Djasra Ratébaye was commissioned in 2023 by Art & Theology.

Written as a dialogue between Mary, Joseph, and the people of Bethlehem as the couple first arrives in town, this traditional Christmas carol is from the French Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique. As for its approximate date of origin, I found several of its verses appearing as far back as 1703, with a complete version showing up in an 1817 carol collection, but it very well could have circulated prior to that.

The song was famously recorded by Manuela Pioche, Henri Debs, and Guy Alcindor in 1969 on Noël Aux Antilles (reissued on CD in 1993), but overall, I prefer Robert Mavounza’s recording from 2005. In Mavounza’s version, a chorus of voices sings what sounds like “waylo” after every line. The person who translated the song for me is neither Guadeloupean nor Martinican and wasn’t sure of the meaning of the word; he suggested that it’s either a wordless vocable used for embellishment, or else a creole word.

“Joseph mon cher fidèle” is part of the popular repertoire of the Chanté Nwel, the tradition of communal carol singing (with live percussion accompaniment!) that takes place throughout December in Guadeloupe and Martinique. It’s one of the most convivial times of the year.

The Holy Couple’s anxious search for lodging as Mary’s labor pangs begin is a feature of many retellings of the Christmas story, though it’s not present in either of the two Gospel narratives of Christ’s birth. Luke simply says that Joseph “went to be registered [in Bethlehem for the census] with Mary, to whom he was engaged and who was expecting a child. While they were there, the time came for her to deliver her child. And she gave birth to her firstborn son and wrapped him in bands of cloth and laid him in a manger, because there was no place in the guest room” (Luke 2:5–7 NRSV).

Centuries of misinterpretation of the Greek word kataluma as “inn” (instead of the more accurate “guest room”) has led to the invention of an innkeeper character who coldly refuses the needy parents the accommodations they seek. By extension, the whole of Bethlehem is often characterized as inhospitable, for how dare they let the King of the universe be born in a lowly stable? In all historical likelihood, Mary and Joseph were welcomed by family when they got to Bethlehem, but the house where they were staying was full because of the large number of out-of-towners present for the census registration. Adapting to space limitations, Mary and Joseph stayed with their baby in the room where the animals were kept, which would have been attached to the family’s living quarters. Mary most likely would have been assisted by one or more midwives in giving birth and surrounded by family afterward.

Nevertheless, “Joseph mon cher fidèle” is a part of the tradition that imagines a more tense and harrowing birth narrative. When Joseph and Mary arrive in Bethlehem and, hurried by Mary’s increasingly regular contractions, desperately knock on doors to ask for lodging, they are turned away again and again. The townspeople know how suspicious Herod is of strangers, how easily threatened, and they don’t want to risk his ire by harboring one, so they tell the strange couple to go sleep outside somewhere. When Mary tells them she is about to give birth to God, they accuse the couple of trickery and lies; if “God” comes forth from this woman, they chide, it would be some kind of wicked conjuration they produced under the dark cover of shadows.

Joseph reprimands the people of Bethlehem for their rejection and mistrust while Mary resourcefully sets her sights on a distant stable. Joseph laments its unsuitability for such a son as theirs, but Mary reassures him that it will suit Jesus just fine and that God will protect them all through the night. The humble shelter, Joseph concedes, will be made magnificent and holy by the Holy One who inhabits it.

At the hour of midnight, Jesus starts to crown. Mary is ecstatic to meet her son at last, and Joseph sweeps him up into her arms to be showered with love and kisses.

I love that Joseph gets more treatment in this carol than in most others. He gets the last word—the final stanza is in his voice—which is full of such fatherly affection. He and Mary sigh together in relief for a safe delivery and cry together tears of joy, which mingle with the wails of their newborn.

Despite the conflict and stress in the narrative, the music is bright and upbeat throughout. This is, after all, a party carol! Mary maintains a steadfast faith in the God who called and empowered her for the task of bringing God-in-flesh into the world.

This post is part of a daily Advent series from December 2 to 24, 2023 (with Christmas to follow through January 6, 2024). View all the posts here, and the accompanying Spotify playlist here.