ARTICLES:

>> “How Asian Artists Picture Jesus’ Birth from 1240 to Today” by Victoria Emily Jones, December 18, 2023, Christianity Today: My first CT article was published this week! I was asked to curate and introduce a sampling of Nativity art from across Asia. By representing Jesus as Japanese, Indonesian, or what have you, these artists convey a sense of God’s immanence, his “with-us–ness,” for their own communities—and for everyone else, the universality of Christ’s birth.

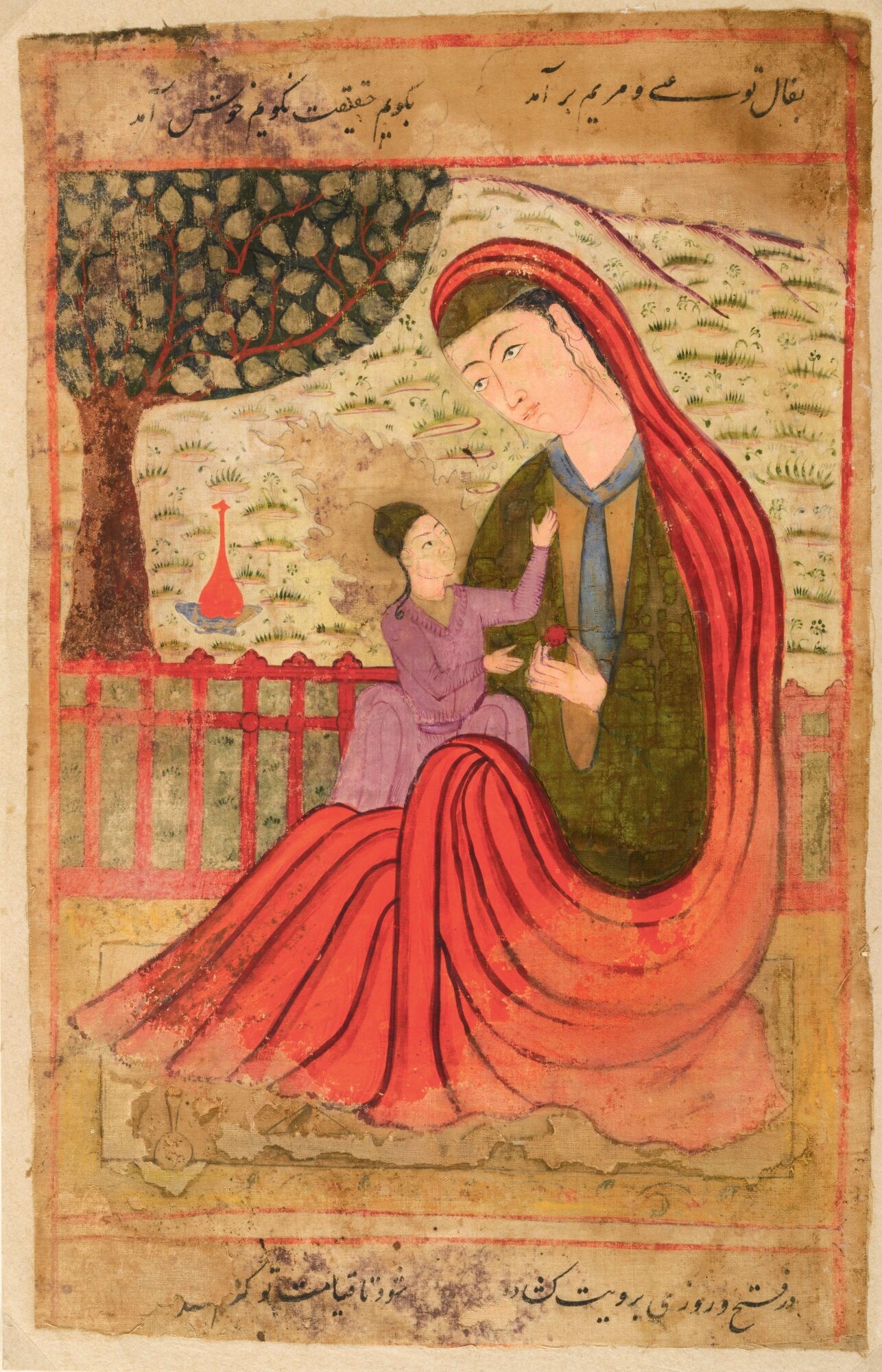

>> “The Story of Christ in Chinese Art: Scholars at Peking University Make a Christmas Portfolio for LIFE,” Life, December 22, 1941, pp. 40–49: In doing research for my Christianity Today article, I found this old article from Life magazine that features eight Chinese watercolors on silk from the collection of Dr. William Bacon Pettus (1880–1959), an American educator and president of the California College of Chinese Studies in Peking (Beijing) in the 1920s and ’30s, which were being exhibited at New York’s American Bible Society at the time. With the ordination of six Chinese bishops by Pope Pius XI in 1926, the Chinese Catholic Church was transitioning from a mission church to an indigenous local church, and Chinese-style religious art—much of it coming out of the art department of the new Catholic University of Peking (Beiping Furen Daxue)—was part of that localization. Productivity seems to have continued at Furen during the Japanese occupation, as this article attests. Many of the students and faculty were recent converts to Christianity, though the article reports that non-Christians also enrolled and taught in the art program.

Here is one of the paintings by Lu Hongnian, who sometime after this article was published, in part through his having engaged the New Testament as inspiration for his paintings, became a Christian and took the name John. It shows the Holy Family in a mountainside cave, Mary gazing adoringly at her newborn son as Joseph brings more straw to cushion him. Beside them, an angel holds up a lantern for light, while two shepherd children approach from the entrance, eager to meet their Savior.

+++

SONGS:

>> “Philippians 2:5–11” by HARK Music: This song takes a traditional Thai melody, arranged by Tirasip Kraitirangul, and puts it to a Thai translation of the famous Christ Hymn from Philippians 2. It’s performed by the HARK Duriya Tasana Singers (feat. Somchairak Sriket and Damrongsak Monprasit) and Dancers, filmed on location at Chaloem Kanchanaphisek Park in Bangkok. The song is from HARK’s Thai Hymns Album (2014), which can be downloaded for free at https://harkpublications.com/?product=thai-hymns-album-2. The two-stringed bowed instrument you see at 3:21 is a saw u.

The Duriya Tasana (“Curators of the Arts”) ensemble was formed in 2012 under the commission of the Thai-Psalms Project, an endeavor to create Thai traditional and classical music settings for the psalms of the Bible. Many of the members are affiliated with the Bunditpatanasilpa Institute of Fine Arts in Bangkok. Thanks to my friend Janet, whose sister is preparing a move to Thailand, for alerting me to this group!

>> “Jesus You Come” by Tenielle Neda, performed with Jon Guerra: This song by the Australian singer-songwriter Tenielle Neda [previously], which she sings with Jon Guerra, makes a nice complement to the Thai song above. The performance is from “Songs for Hope: A TGC Advent Concert” on December 6, 2020.

+++

MIDDLE ENGLISH LULLABY: “As I lay upon a night”: Medievalist Eleanor Parker introduces a charming Christmas lullaby from fourteenth-century England, a dialogue between Mary and the Christ child, and provides a modern English translation of its thirty-seven stanzas. In the Middle Ages, says Rosemary Woolf, the subject matter of lullabies was often a prophecy of the baby’s future—presumably a romantic promise of great and happy achievements. But here it is the child who relates the future to his mother, thus providing the material for his own lullaby.

+++

ART VIDEO: “Third Sunday of Advent: Ethiopian Art: Gospel Book” by James Romaine: Every December, my friend James Romaine, an art historian who teaches at Lander University, publishes four videos on his Seeing Art History YouTube channel related to the themes of the season, part of his annual Art for Advent series. This year he’s chosen to focus on Ethiopian art, covering illuminations from two different manuscripts, a diptych icon, and a rock-hewn church.

In this video Romaine discusses the formal qualities of two paintings from a sixteenth-century Ethiopian Gospel-book, the identity of the figures, and the liturgical context of the book, including the use of the red veil that’s attached at the top, which, Romaine says, “both protects and sanctifies the icon,” creating a sense of anticipation for the Orthodox believer who, in faith, lifts the veil to see what is revealed.