LECTURE: “Light in Sacred Space: Light from the Cave” by Matthew J. Milliner and Alexei Lidov, December 19, 2019, Bridge Projects, Los Angeles: This double lecture about the role of light in Christian spirituality and theology was organized to coincide with the premiere of 10 Columns, an immersive light installation by Phillip K. Smith III that Bridge Projects commissioned for their inaugural exhibition.

While the Light & Space movement was born in Southern California in the 1960s, in many ways it participates in a much longer history of artists in dialogue with the phenomena of light. This presentation by two art historians, Matthew Milliner and Alexei Lidov, will begin with Milliner exploring the unexpected resonance of Phillip K. Smith III’s work with Byzantine and Gothic traditions. Lidov will then expand on these ideas with his scholarship in the Eastern Orthodox tradition and its long history of engaging light and mysticism. What kinds of insights might come when Light and Space artists, including Phillip K. Smith III, are put in conversation with ancient Orthodox Christian concepts of the nativity and uncreated light? [source]

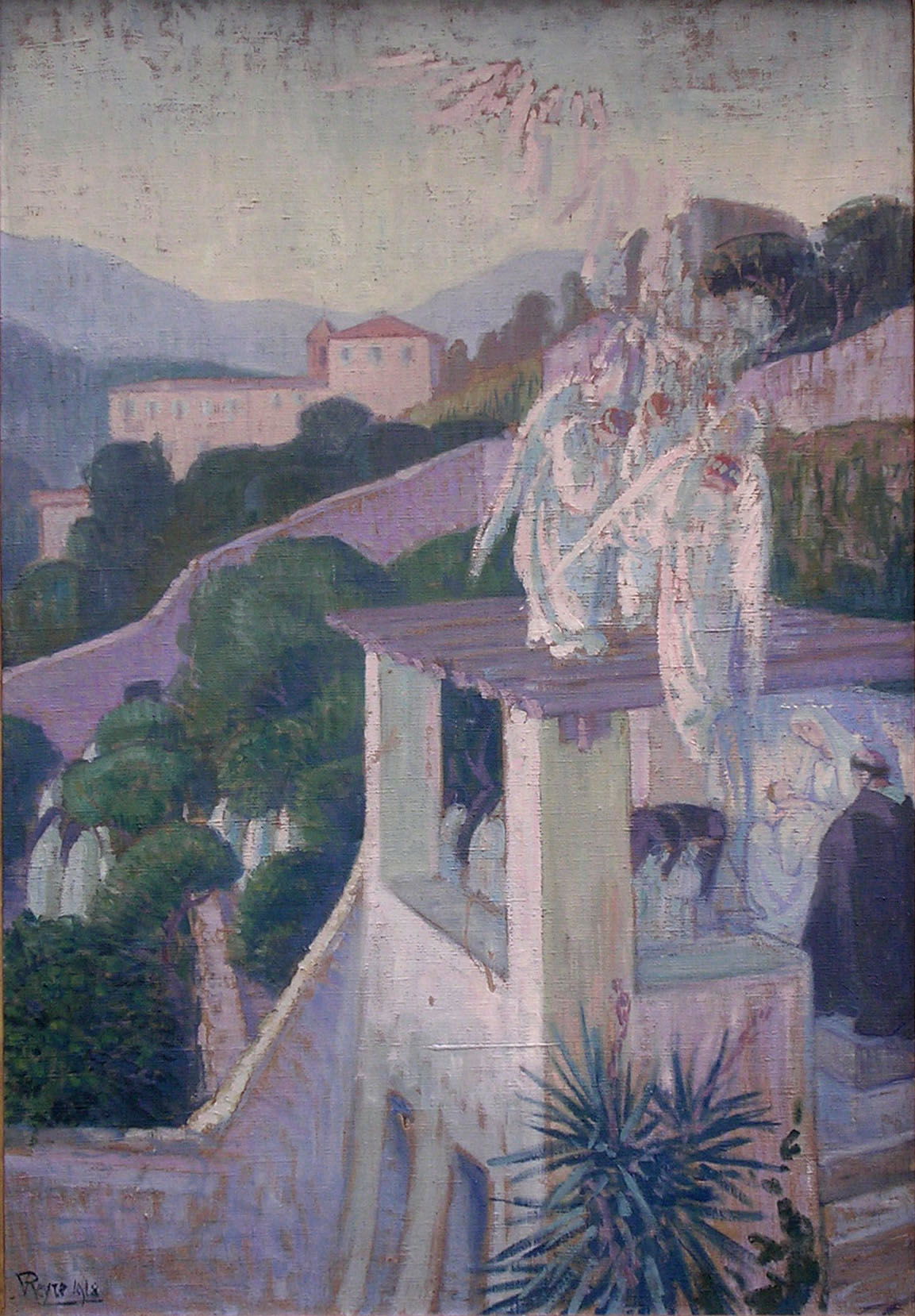

Milliner speaks for the first forty minutes, discussing Nativity and Transfiguration icons and their correlatives in the West and making, as always, fascinating connections between art of the past and present. For example, he overlays Olafur Eliasson’s Ephemeral Afterimage Star (2008) on Rublev’s Transfiguration icon (19:19), and Ann Veronica Janssens’s Yellow Rose on an Adoration of the Magi illumination from a fifteenth-century book of hours at the Getty (26:32). He also introduced me to a fascinating medieval manuscript illumination from Germany (which he in turn learned about through Solrunn Nes) that combines the light of Bethlehem and Tabor—two Gospel scenes in one. Don’t miss the quote by Gregory of Nazianzus.

Combining art history and theology (he has advanced degrees in both), Milliner’s talk is organized as follows:

- Thessaloniki | Gregory Palamas (d. 1337)

- Constantinople | Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (d. ca. 500)

- Paris | Abbot Suger (d. 1151)

- Los Angeles | Phillip K. Smith III (b. 1972)

+++

ART VIDEOS:

>> “A 60-second introduction to ‘The Nativity at Night’”: One of my favorite Nativity paintings! By fifteenth-century Dutch artist Geertgen tot Sint Jans, a lay brother in the religious order of St. John. In this video from the National Gallery in London, a camera scans over the painting as an atmospheric soundscape plays and captions guide us in looking at the details.

>> “Mother and Child Commission”: In this twelve-minute “making of” video, filmmaker Nick Clarke talks to artist Nicholas Mynheer over the first half of 2020, tracing his progress on the life-size Mother and Child sculpture that was commissioned by the Community of St Mary the Virgin, Wantage, an Anglican convent in Oxfordshire. I was struck by, from the looks of it, the physical demands of the sculpting process—the strength and endurance required to chip away daily at blocks of stone outside in winter, until they yield the shape you desire, then the logistics of attaching the blocks with steel, which weigh nearly a ton collectively, and disassembling, transporting, and reassembling them for installation. I was also interested to hear Mynheer discuss the expressive capabilities of English limestone—how you can convey emotional and sartorial subtleties, for example, through the precise angling of the chisel.

Mother and Child was installed in the outdoor reception area of St Mary’s on April 12, 2021; you can watch a video of the installation here. “In very, apparently, simplified form, there is so much tenderness, energy, and something new,” says Sister Stella, the sister in charge, about the sculpture. “Jesus isn’t going to be held back. Her son’s going to go places.”

To learn more about Nicholas Mynheer, visit his website, https://www.mynheer-art.co.uk/. You can also read the artist profile I wrote on him for Transpositions in 2017.

+++

SONGS:

>> “Corazón Pesebre” (Heart Manger) by Rescate: A follower of the blog introduced me to this Christmas song from Argentina, and I dig it! Released as a single in 2017, it’s about turning our hearts into a manger to receive Christ. Read the Spanish lyrics in the YouTube video description.

The song is by the highly popular Argentinian Christian rock band Rescate, active from 1987 to 2020. Their lead singer and main songwriter, Ulises Eyherabide, died of cancer in July.

>> “Hallelujah, What a Savior!” (Christmas Version), performed by Providence Church, Austin, Texas: In 2012 Austin Stone Worship songwriters Aaron Ivey, Halim Suh, and Matt Carter rewrote the lyrics to Philip P. Bliss’s classic “Hallelujah, What a Savior!” to make them more Christmas-centered and added a new refrain; their version was released that year on A Day of Glory (Songs for Christmas). Here the song is performed by another Austin worship team—Jordan Hurst, Jaleesa McCreary, and Brian Douglas Phillips from Providence Church—for a virtual worship service on November 29, 2020. Instead of using the Austin Stone refrain, they quote Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” between verses.