SONGS:

>> “He Is Lord (In Every People),” adapt. Gregory Kay: In this video from 2021, members of Spring Garden Church in Toronto take turns singing the popular twentieth-century worship song (of unknown authorship) “He Is Lord” in their native languages: English, Portuguese, Arabic, Korean, and Chinese. Greg Kay, one of the church’s copastors, added a fun refrain that highlights the global character of Christianity and the lordship of Christ over all creation, which everyone joins in on. Love this idea! [HT: Liturgy Fellowship]

>> Easter Medley performed by Infinity Song, feat. Victory Boyd: Infinity Song is a sibling band from New York City that was led for years by Victory Boyd, who is now focusing on her solo music career; its current members, represented in this video from 2021, are Abraham, Angel, Israel, and Thalia “Momo” Boyd. (Victory is singing lead.) The group combines the songs “In the Name of Jesus” by David Billingsley, “Jesus Is Alive” by Ron Kenoly [previously], and “Redeemer” by Nicole C. Mullen into an Easter medley at Fount Church in New York.

>> “Yessu Jee Utheya” (یسوع جی اُٹھیا) (Jesus Is Risen), performed by Tehmina Tariq: Tehmina Tariq is a prolific gospel singer from Islamabad, Pakistan. Here she performs a song in Urdu by Nadir Shamir Khan (words) and Michael Daniel (music). Press the “CC” button on the YouTube video player to follow along with the lyrics. For a more recent Easter song that Tariq recorded, see “Zinda Huwa Hai Masih” (The Messiah Is Risen). [HT: Global Christian Worship]

+++

MEDIEVAL MYSTERY PLAY: The Harrowing of Hell from the York cycle, produced by the YMPST (York Mystery Plays Supporters Trust): From the mid-fourteenth to mid-sixteenth century in England, during the feast of Corpus Christi in early summer, villagers used to enact stories from the Bible on moveable stages called pageant wagons, which would wheel through town making various stops for performance. Playing the roles of sacred personages were not professional actors but members of the trade guilds. Such plays were banned in Tudor times but since the mid-twentieth century have enjoyed a revival.

One of the few complete surviving English mystery play cycles, consisting of forty-eight individual verse dramas of about twenty minutes each, is the York Mystery Plays, named after the historic town where they originated. One of the plays, assigned to the town saddlers, is The Harrowing of Hell. The following video is a 2018 performance sponsored by the York Mystery Plays Supporters Trust, also available on DVD. You can follow along with the script at TEAMS Middle English Texts, though note that the players do adapt it lightly. Learn more at https://ympst.co.uk/.

For a preview of the language, here’s Adam’s speech toward the end, after Christ binds Satan and casts him into a fiery pit (I love the alliterative phrase “mickle is thy might”!):

A, Jesu Lorde, mekill is thi myght

That mekis thiselffe in this manere

Us for to helpe as thou has hight

Whanne both forfette, I and my feere.

Here have we levyd withouten light

Foure thousand and six hundreth yere;

Now se I be this solempne sight

Howe thy mercy hath made us clene.Modern English translation:

Ah, Lord Jesus, mickle [great] is thy might

That makest thyself in this manner

To help us as thou hast said

When both of us offended thee, I and my companion [Eve].

Here have we lived without light

For four thousand six hundred years;

Now see I by this solemn sight

How thy mercy hath made us clean.

The YMPST performance incorporates modern elements in the music and costuming, including an electric guitar–driven rendition of the American gospel song “Ain’t No Grave” at the opening and closing.

+++

ART COMMENTARIES:

Below are discussions of two medieval English artworks of the Harrowing of Hell, one of my favorite religious subjects. In modern-day parlance, the word “hell” (an English translation of the Greek “Tartarus” or “Hades” or the Hebrew “Sheol”) typically connotes a place of eternal torment where the damned go, but in Christian theology it was long used more broadly to refer to the compartmentalized netherworld where both righteous and unrighteous souls go after death to await the general resurrection that will take place at Christ’s return.

>> “The Harrowing of Hell” (Smarthistory video): Drs. Nancy Ross and Paul Binski discuss a fifteenth-century alabaster that’s in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. What sticks out to me—the commentators mention it only briefly—is that Christ stands on a green, flowery lawn! The artist is probably alluding to the springtime, the new life, that Jesus’s resurrection ushered in: the redeemed exit the hellmouth, barefoot like their Lord, onto this lush grass. This detail reminds me a bit of Fra Angelico’s Noli me tangere fresco at San Marco in Florence.

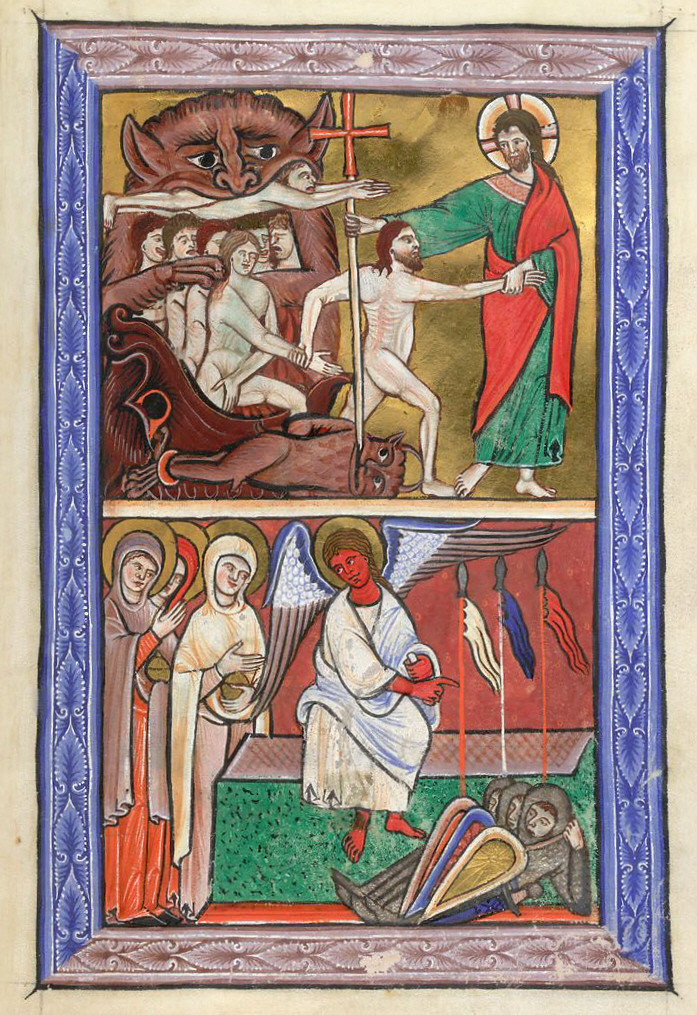

>> “Under the Earth” by Joanna Collicutt: The Visual Commentary on Scripture is a free online resource that provides material for teaching, preaching, researching, and reflecting on the Bible, art, and theology. For one of her three VCS-commissioned “visual commentaries” on Philippians 2:1–11, Rev. Dr. Joanna Collicut has selected an illumination of the Harrowing of Hell from a thirteenth-century psalter. The Christ Hymn that forms the meat of this passage celebrates Jesus’s descent and ascent, and in verse 10 it says that at his name, every knee will bow in heaven, on earth, and “under the earth.” This phrase had never stood out to me until now.