The final Sunday of the liturgical year—which this year is November 24—marks the Feast of Christ the King. This festival celebrates the reign of Jesus Christ over all of creation and every aspect of our lives.

“The belief in Christ as King finds its roots in the Christian understanding of Jesus as the Messiah, whose reign exists as both a present reality and a future hope,” writes Ashley Tumlin Wallace on her blog The Liturgical Home. “In the here and now, his reign manifests in the lives of believers who seek to live under his lordship. But the Feast of Christ the King also carries a sense of eschatological anticipation, signaling the ultimate culmination of time when the reign of Christ is fully realized.”

Unlike some who sit on earthly thrones, Christ is no tyrant; he’s a benevolent ruler who leads with love and perfect wisdom. He is high and lifted up, and yet he stoops down to us and attends to our cries. He’s so committed to our flourishing that he became one of us and sacrificed himself to save us from the Evil One and reconcile us to God. We owe him our praise, our deference, our all.

For Christ the King Sunday, I put together a Spotify playlist of songs that extol Christ as king of the cosmos and of our own hearts.

It includes traditional hymns like “All Hail the Power of Jesus’ Name” (below, sung by Paul Zach), “Come, Christians, Join to Sing,” “All Creatures of Our God and King,” “All People That on Earth Do Dwell,” “Praise to the Lord, the Almighty,” “O Worship the King,” “Crown Him with Many Crowns” . . .

In looking up hymns, I was delighted to find a new-to-me one from the nineteenth century by Josiah Conder called “The Lord Is King,” which Navy Jones set to a buoyant new tune:

There’s one song on the list whose text dates all the way back to the fifth century. Written in Latin by the Christian poet Sedulius, “Regnavit Dominus” (The Lord Is King) combines praises to the One who conquered death and feeds us with himself with the humble plea, “Kyrie eleison” (Lord, have mercy). Owen and Moley Ó Súilleabháin sing it to a twelfth-century melody:

The playlist also features several psalm settings, including two of Psalm 93, which opens,

The LORD is king; he is robed in majesty;

the LORD is robed; he is girded with strength.

He has established the world; it shall never be moved;

your throne is established from of old;

you are from everlasting.

One is by Jacob Mwosuko, a member of the Abayudaya (People of Judah) Jewish community near Mbale in eastern Uganda. The text is in Luganda. Though Jews would read “LORD” as referring to God the Father, ever since the early church Christians have confessed Jesus not only as Lord (Master) but also as LORD (YHWH), consubstantial and co-eternal with the Father, sharing with him all rule, authority, power, and dominion.

Also from Africa, there’s the Resurrection-rooted salsa song “Jesus Reigns” by Joe Mettle of Ghana, which I learned while attending worship at a Nigerian friend’s church plant for African Christians in Maryland:

On a softer note, there’s the piano ballad “Wondrous Things” by Sandra McCracken, Patsy Clairmont, and JJ Heller of FAITHFUL, a collective of female Christian authors and artists formed in 2019. It lauds Jesus as king to the poor, the oppressed, and the brokenhearted. Heller and McCracken perform it with Sarah Macintosh in the following video:

This next one is more of a nostalgic pick for me: “Make My Heart Your Throne”:

Over two decades ago, when I was a young high schooler, I attended a Christian retreat. The worship leader for the weekend was a man named Carl Cartee, and I remember being struck by this original song of his that we all sang one night. Its words and melody imprinted on me, and all these years later I still find myself sometimes singing them in private as a prayer that Christ would be foremost in my affections and that I would cede control to him.

One of the keenest depictions of Christ’s kingship in scripture is in the book of Revelation, where his glory and triumph are on full display and he’s surrounded by worshipping throngs. Chapter 19, where the exiled John describes “the loud voice of a great multitude in heaven,” is the source text of the song “He Is Wonderful,” sung by Lowana Wallace with Lana Winterhalt and Josh Richert:

These three overlaid, harmonized vocal lines are so enthralling!

Wallace’s song is a simplified arrangement of “Revelation 19:1” by A. Jeffrey LaValley, who wrote it in 1984 for the gospel choir of New Jerusalem Baptist Church in Flint, Michigan, where he served as music director. You can listen to a more recent performance of “Revelation 19:1” on the album Jesus Is King (2019) by the Sunday Service Choir under the direction of Jason White, or in this Mav City Gospel Choir video from 2021, which features soloist Naomi Raine. The choir is directed by Jason McGee:

The build to such fullness of sound . . . wow! It really is evocative of the ample rejoicing in heaven around God’s throne that John the Revelator narrates—“like the sound of many waters and like the sound of mighty thunderpeals” (Rev. 19:6).

For a multilingual (English-Korean-Spanish) arrangement performed by students and staff at Fuller Theological Seminary in California, see here.

This is just a sampling of the eighty-plus songs on Art & Theology’s “Christ the King” playlist, exalting the One who lives and reigns supreme in the heavens and who will one day bring his kingdom to full fruition on earth.

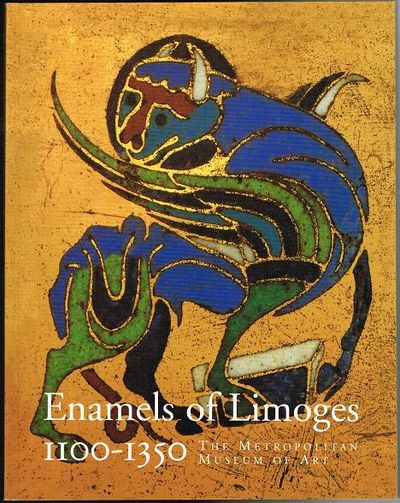

Cover art: John Piper (British, 1903–1992), Christ in Majesty, 1984, East Window, Chapel of St John Baptist without the Barrs, St John’s Hospital, Lichfield, Staffordshire, England