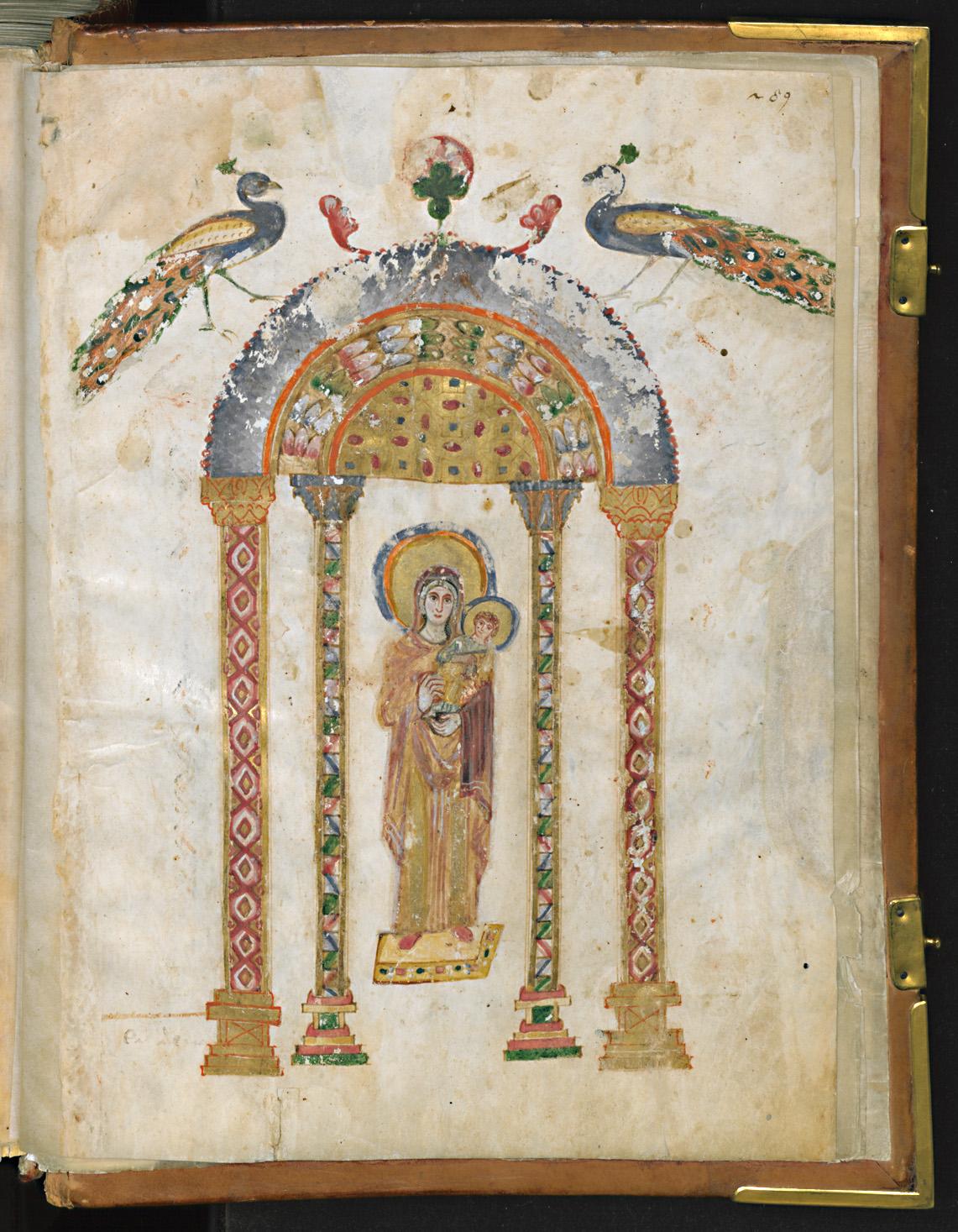

LOOK: Nativity icon from St. Catherine’s Monastery

This Coptic icon of the Nativity bears all the traditional elements of Nativity icons. It shows Mary reclining in a cave next to her newborn son, Jesus, who lies in a manger, being affectionately licked by an ox and ass. Why those two animals? Because the church fathers read Isaiah 1:3 into the scene, which says, “The ox knows its owner and the donkey its master’s crib.”

The starry semicircle at the top represents the heavens. A thick beam of light descends from it onto Christ, confirming his divine paternity. On either side, from behind the grassy hills, angels rejoice, bringing glad tidings of the birth.

From the right, three magi approach with their gifts (unusually, their horses are placed apart from them in the bottom left), and in the center, a shepherd plays a pipe while his flock frolics on the grass.

In the bottom left, Joseph sits dejectedly with his head in his hands. He is being assailed once again by doubt as to Jesus’s true paternity. Could Mary’s outrageous story really be true? Or was she sexually unfaithful? In some Nativity icons Satan appears to Joseph in the guise of an old man to tempt him to distrust Mary and to doubt Jesus’s divinity. Anyone would be a fool to believe it, he taunts. It’s possible that the man with the pointed red cap at the far right of this icon is meant to be the devil on his way to Joseph, but if so, it would be an odd compositional choice. Anyway, in Nativity icons, Joseph stands for all skeptics, for those who struggle to accept that which is beyond reason, especially the incarnation of God.

Next to Joseph, two midwives bathe Jesus in a basin. (Jesus appears twice in the composition. He’s identified by the cross-shape in his halo.)

Art historian Matthew J. Milliner, who specializes in the Byzantine era, describes the Orthodox iconography of the Nativity in a 2021 podcast episode of For the Life of the World [shared previously]:

There’s just something wonderful about the classic Nativity icon. When you look at this, you’ve got Joseph in the corner. . . . And then you have this dome that is overarching the scene. That is, speaking in Charles Taylor’s terms, that’s the “immanent frame”—that’s the cosmos as we know it. And it’s shattered! By what? By the light that comes from outside. In other words, the Kantian universe has been pierced and God has revealed himself and said, “This is how I choose to come into the world.”

And there you have the Virgin Mary, and she almost looks seed-like when you look at these icons. She’s on her side because, thank you very much, she just gave birth. And there’s Christ. And the donkey and the ox are there, symbolizing both Jew and Gentile. In other words, the book of Romans in one shot. Boom. Right there.

Then you’ve got the magi sometimes off in the distance, to symbolize all corners of the earth, to symbolize most in particular the Assyrian Church of the East, the expansion of Christianity all the way to the Pacific Ocean by like the fifth century, folks. Gotta remember that! These are the Christians whom we have lost contact with. The global reality of Christianity is communicated by these icons.

And then, of course, you’ve got the shepherds to symbolize, we might even say, all classes incorporated into this faith—not just across the globe, but across socioeconomic status. All of it is communicated just by meditating upon it.

And then you have this cavern—not some sweet little stable, but a cavern, a cave. And folks, it’s the cave of your own psyche as well. It’s a depth-psychology dimension of the Christian tradition. A Nativity icon is what God wants to do in your soul. This is intended to be a spiritual experience.

The dating of the particular icon pictured above has been debated. It is circulating in many places online with an attribution of “seventh century,” perhaps in part because of its use of encaustic (a common medium for earlier icons). But Father Akakios at St. Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai, the institution that owns and houses the icon, told me that’s probably too early, that it’s more likely a later icon that incorporates earlier elements.

From the Sinai Digital Archive, it appears that Kurt Weitzmann, an art historian from Princeton University who had the icon photographed on one of his four research expeditions to Sinai in the late 1950s and early ’60s, proposes the sixteenth or seventeenth century as its likely time of creation. Cathy Pense Garcia, head of Visual Resources Collections at the University of Michigan (which manages the Sinai Digital Archive jointly with Princeton), was unable to confirm an approximate date and said that more scholarly research is needed.

It’s such a wonderful icon! I hope to see some academic writing about it in the future, as my research turned up next to nothing.

LISTEN: “Kontakion of the Nativity of Christ” by Romanos the Melodist, 6th century | Chanted by Fr. Apostolos Hill, 2016

Today the Virgin cometh unto a cave to give birth to the Word who was born before all ages, begotten in a manner that defies description. Rejoice, therefore, O universe, if thou should hear and glorify with the angels and the shepherds. Glorify him who by his own will has become a newborn babe and who is our God before all ages.

(Η Παρθένος σήμερον, τον προαιώνιον Λόγον, εν σπηλαίω έρχεται, αποτεκείν απορρήτως. Χόρευε, η οικουμένη ακουτισθείσα, δόξασον, μετά Αγγέλων και των ποιμένων, βουληθέντα εποφθήναι, Παιδίον νέον, τον προ αιώνων Θεόν.)

This is the prooimoion (prologue) to Romanos the Melodist’s kontakion on the Nativity of Christ; the other twenty-four stanzas can be read in a translation by Ephrem Lash in St. Romano, On the Life of Christ: Kontakia—Chanted Sermons by the Great Sixth-Century Poet and Singer (HarperCollins, 1995).

This post is part of a daily Christmas series that goes through January 6. View all the posts here, and the accompanying Spotify playlist here.