Today’s format is a little bit different, in that the visual art and music are part of a singular video piece which also prominently features dance—so, multiple media all wrapped up into one.

Every year in the church calendar, December 28 commemorates the Massacre of the Innocents—the boys of Bethlehem slain by agents of the state, deployed by Herod, who feared the perceived threat they posed. The story is told in Matthew 2:16–18 and quotes the prophet Jeremiah:

A voice was heard in Ramah,

wailing and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children;

she refused to be consoled, because they are no more.

While the remembrance marks this ancient event specifically, the church also takes the occasion to pray for present-day innocents who have been victimized by the powerful. For example, the collect (succinct prayer) for this day from the Book of Common Prayer reads:

We remember today, O God, the slaughter of the holy innocents of Bethlehem by King Herod. Receive, we pray, into the arms of your mercy all innocent victims; and by your great might frustrate the designs of evil tyrants and establish your rule of justice, love, and peace; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

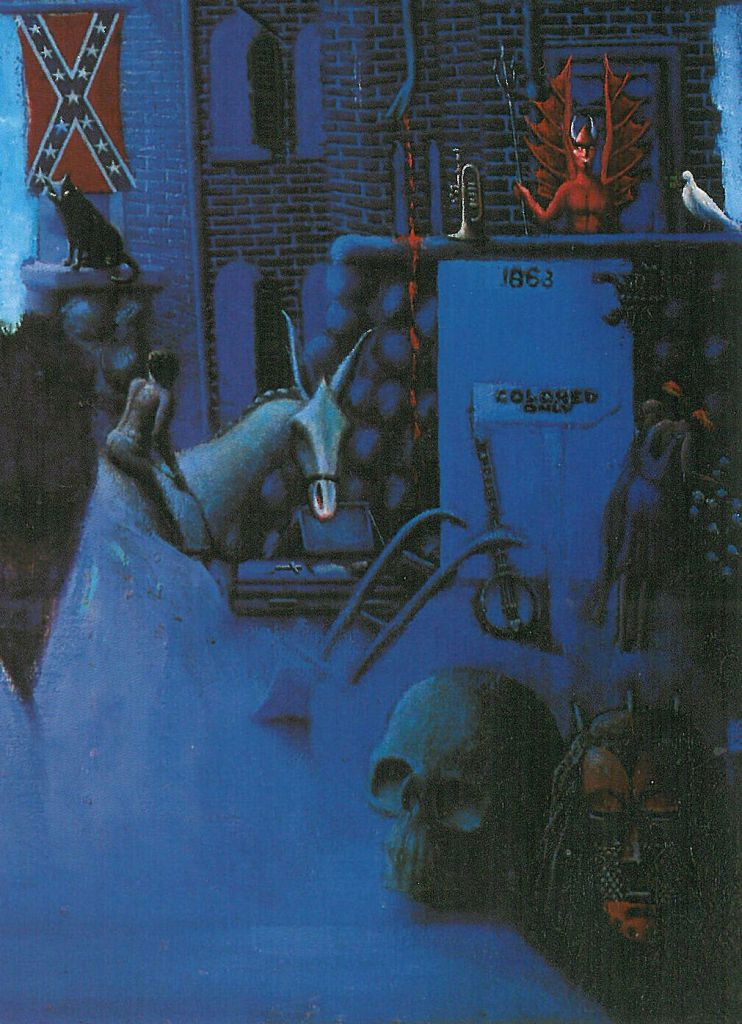

The artists of today’s piece, made in 2019, confront the unjustified killing of Black men in America by police. They do not make the explicit connection to Herod’s massacre, but I do, as I hear, in the many Black mothers who have lost their children to state violence, Rachel weeping and refusing to be comforted. And I see Herod-like rulers who want to silence those wails and reverse the progress made in awareness and reform.

(Related posts: Saltcellars by Rebekah Pryor and “Mothers and Shepherds” by Common Hymnal; Antiquarum Lacrimae (The Tears of Ancient Women) by Joan Snyder and “Neharót Neharót” by Betty Olivero)

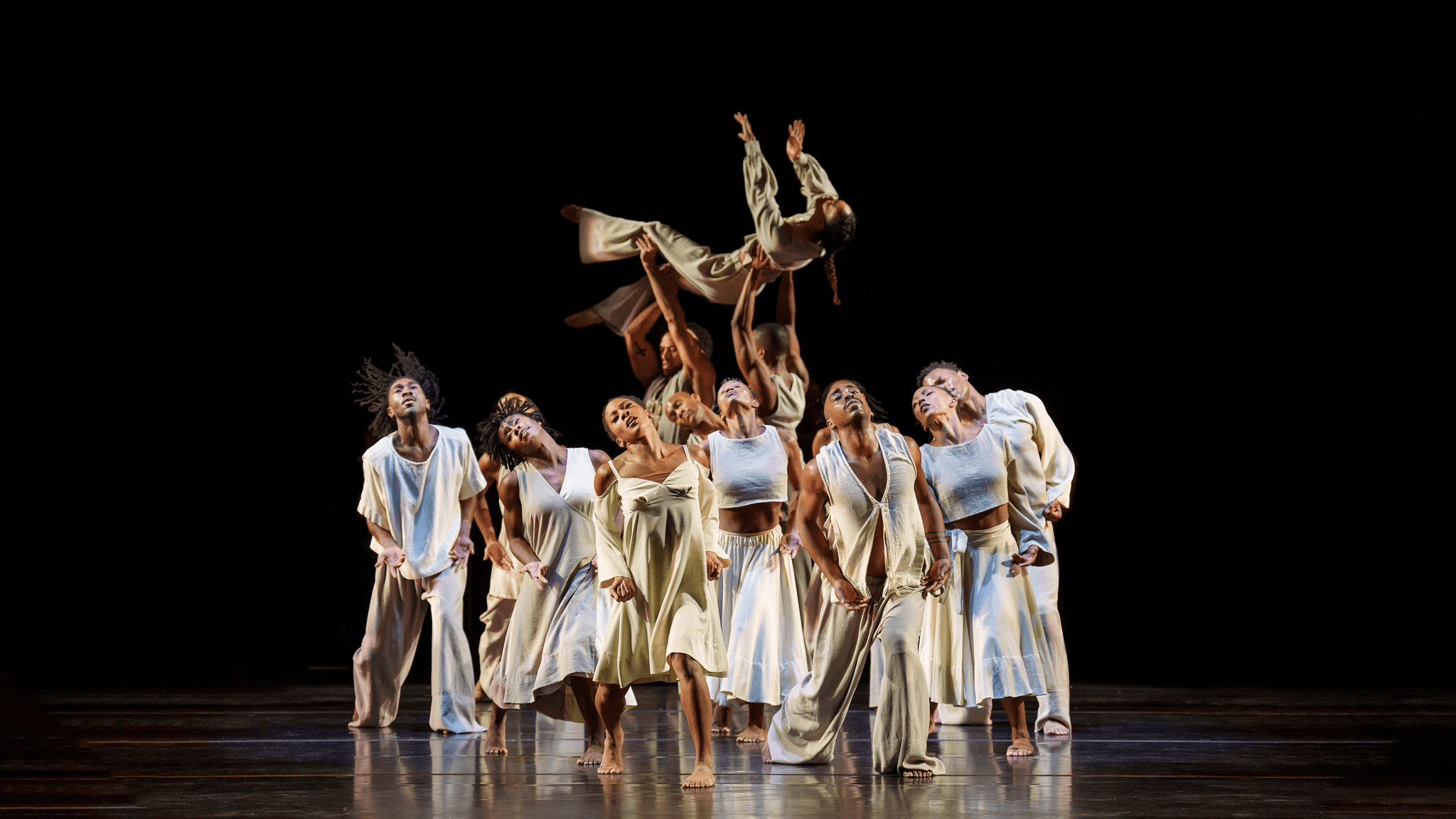

LOOK & LISTEN: The Ritual of Being, a site-specific dance performance by T. Lang in front of the Mothers March On mural by Sheila Pree Bright, 2019

The 2010s was a decade of racial reckoning in America. In response to neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman’s killing of the unarmed Black teen Trayvon Martin and subsequent acquittal, the Black Lives Matter movement was founded in 2013, demanding policing and criminal justice reform and the safety of marginalized Black communities. BLM activism and the continual miscarriages of racial justice that prompt it received ample media coverage all the way through the movement’s peak in 2020 with the murder of George Floyd. That coverage has lessened in the last few years, but the movement is still active, and mothers still bear the wound of their slain children.

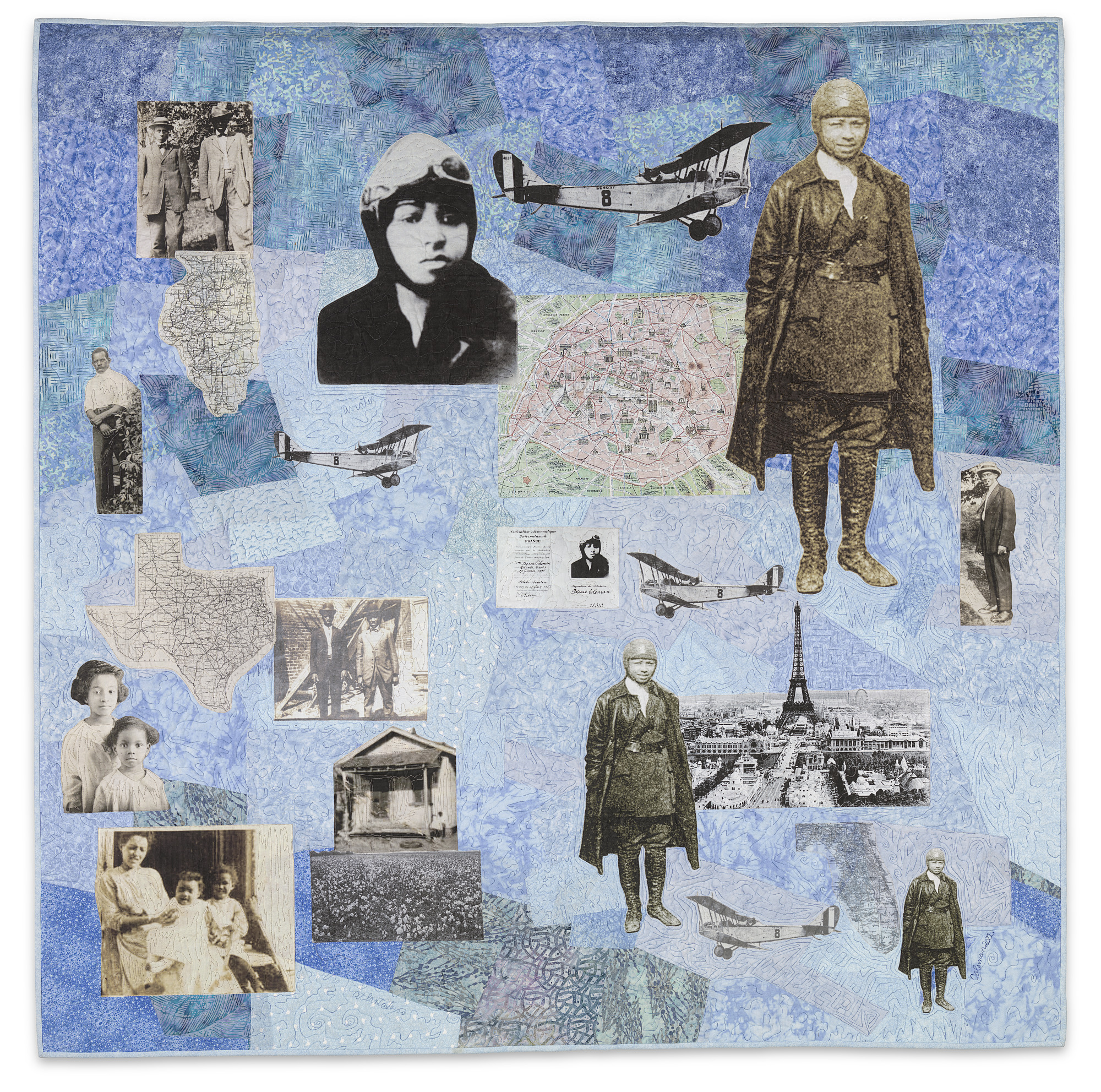

In 2019, the lens-based artist Sheila Pree Bright, author of #1960Now: Photographs of Civil Rights Activists and Black Lives Matter Protests, brought together nine mothers who are fighting for justice for their boys whose lives were taken from them by police. She wanted to give them a safe space to talk, and to photograph them. The portrait Mothers March On depicts, from left to right, Tynesha Tilson (mother of Shali Tilson), Wanda Johnson (mother of Oscar Grant), Felicia Thomas (mother of Nicholas Thomas), Gwen Carr (mother of Eric Garner), Monteria Robinson (mother of Jamarion Robinson), Dr. Roslyn Pope (author of An Appeal for Human Rights), Dalphine Robinson (mother of Jabril Robinson), Patricia Scott (mother of Raemawn Scott), Montye Benjamin (mother of Jayvis Benjamin), and Samaria Rice (mother of Tamir Rice).

Carr, whose son died in the chokehold of an NYPD officer who ignored his cries of “I can’t breathe,” is the focal point of the image, with her arms outstretched and fingers spread. This body language connotes an offering of self to the cause of justice and a readiness to receive it. That her hands are open rather than clenched in a fist indicates unguardedness, while her planted feet indicate firmness.

The woman in glasses beside Carr is Roslyn Pope, who died in 2023. A mother to two daughters, she had not herself lost a child to police violence, but she was part of Mothers March On on account of her seminal civil rights work in Atlanta. In 1960, while serving as president of the student government at Spelman College, she drafted the manifesto An Appeal for Human Rights, announcing the formation of the Atlanta Student Movement, whose campaign of civil disobedience would contribute to the dissolution of racist Jim Crow laws across the region. In a 2020 interview for the sixtieth anniversary of the manifesto’s publication, Pope expressed concern that some of the students’ hard-fought gains were being eroded, telling the Associated Press, “We have to be careful. It’s not as if we can rest and think that all is well.”

Sheila Pree Bright describes the photo she composed:

The Mothers March On photographic project is about Black women who have witnessed the tragic loss of their children who have fallen to police brutality. . . . This project pays homage to the sacrifices, wisdom, and guidance of Black mothers as nurturers and protectors who are passing on a legacy of determination and love, showing how they are fierce and tender, protective and vulnerable, and strong and soft. I’m honoring the struggles of Black mothers, celebrating the beauty of their strength and resilience. These mothers continue to march on for Human rights for their children to bring attention to the urgent need for police reform and the systemic racism that continues to fuel police brutality against Black bodies since slavery.

La Tanya S. Autry writes for Hyperallergic:

Bright’s depiction . . . stresses Black mothers’ memory, determination, love, and corporeality. Through the repetition of standing figures, the portrait insists on the integrity of Black bodily form. The women speak back to lynching culture. With rose petals at their feet, like fallen bodies of their murdered sons, these mothers, on the front-lines of state violence, refuse to relent. They know who and what has been taken from them; they will never forget. . . .

The various activist work of these mothers is astounding, and they include organizing family support groups, such as Georgia Moms United, legislative advocacy of Georgia House Bill 378 (Use of Force Data Collection Act) to track police violence, and developing youth centers, such as the Tamir Rice Afrocentric Cultural Center.

Bright printed the portrait in large scale and pasted it on the side of a brick retail building at 190 Pryor Street in Atlanta, Georgia, near the Georgia State Capitol. Then, for ProtectYoHeART Day in Atlanta, she and the performance artist T. Lang collaborated on a video piece at that site, where T. Lang dances before the mural to the aching instrumental jazz piece “Alabama” by the saxophonist John Coltrane. (Coltrane wrote the music as a memorial for the four girls who were murdered by Ku Klux Klansmen at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham in 1963; learn more here.) Clothed in a fringe dress, T. Lang spins, jerks, reaches, heaves, throws herself against the wall, crouches, withers, bursts, climbs, pulls, and walks forward, movements of grief and struggle capped by resolve.

A temporary installation, the Mothers March On mural is no longer on Pryor Street.

I first learned about Sheila Pree Bright’s photography from a compelling series of hers that I saw at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, titled Young Americans. In it she invited people across the US between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five to pose with the American flag in whatever way they felt most comfortable. “My practice moves between documentary and conceptual work, from portraiture to constructed realities—always grounded in truth, history, and lived experience,” Bright says.