One of the joys of blogging at Art & Theology is being introduced to new artists by my readers. I was pleased to receive in the mail recently, as a gift from one such reader, a color booklet and a 2018 documentary on the art of Dom Gregory de Wit (1892–1978), a Dutch artist and Benedictine monk who between 1938 and 1955 lived in the United States painting murals for Catholic churches and monasteries. This was the first time I’ve encountered the artist, and I enjoyed getting to know him better through these materials.

All photos in this post are provided courtesy of Edward Begnaud or Stella Maris Films.

Gregory was born Jan Aloysius de Wit on June 9, 1892, in Hilversum, Netherlands. He entered the monastic life in 1913 at age twenty-one, joining Mont César Abbey in Leuven, Belgium, and there taking the name Gregory. (His interest in liturgy and ecumenism is what drew him to that particular abbey.) de Wit was passionate about art making since a young age, and his order encouraged him to further develop his talent as a painter. He therefore studied at the Brussels Academy of Art, the Munich Academy, and throughout Italy. In 1923 he exhibited at The Hague and ended up selling forty-five paintings in one month! He then went on to fulfill three sacred art commissions—one in Bavaria, two in Belgium—while continuing to live as a monk.

In 1938, Abbot Ignatius Esser of Saint Meinrad Archabbey in southern Indiana met de Wit in Europe and invited him to design and execute paintings for the abbey’s church and chapter room—which he gladly accepted.

Here he started to develop his own style, which would come to be marked by brilliant (sometimes garish) colors, bold outlines, distortion or disfiguration (e.g., disproportionate hands), and “overlapping” perspective.

In Christus, Jesus is borne upward by a red-winged chariot. In his right hand he holds a victory wreath, and in his left, an open book that declares, EGO SUM VITA (“I am the Life”). The three small Greek letters in the rays of his halo, a traditional device in Orthodox iconography, mean “I am the Living One,” a New Testament echo of God’s “I am who I am” in Exodus 3:14.

+++

Shortly after de Wit arrived in the US, World War II broke out, and even after he completed his work at Saint Meinrad, he couldn’t return to Belgium. Luckily, another stateside commission came his way, from the newly built Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The parish priest, Father Dominic Blasco, hired him to paint a series of murals, which resulted in de Wit’s most polarizing work: his Christ Pantocrator in the apse behind the altar. Many of the parishioners hated it (and I have to say, I’m not partial to it). A humorous anecdote in the documentary recalls Maria von Trapp, who had once visited the church, expressing her horror at the image to de Wit, not knowing he was its artist!

Not only did de Wit’s art garner dislike, but so did his temperamental personality and sometimes irreverent behavior. For example, while at Sacred Heart, he smoked while he painted, dropping cigarette butts onto the floor during services. Although he did have his supporters, he was eventually fired from Sacred Heart. The last painting he did for the church was of the Samaritan woman at the well—descried as “pornographic” by the sisters of the school because of the suggestive way her dress clings to her forwardly posed thigh.

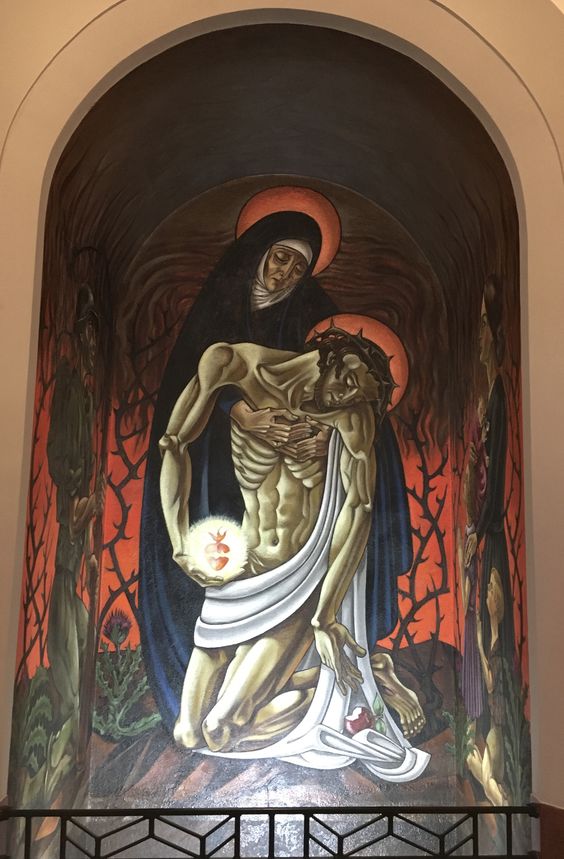

The painting at Sacred Heart that I’m most intrigued by is the Pietà in the narthex, which shows Mary holding her dead son. Genesis 3 is invoked by the thorns that not only crown Christ’s brow but that rise up all around him, symbolic of the curse. What’s more, a half-bitten apple rolls from his limp hand; he, like his forefather, Adam, has tasted death. And this he did willingly out of love, signified by the fiery, thorn-enwrapped heart of his that he holds in his right hand, whose glow illuminates the darkness.

Because de Wit painted this image during the war, it is contextualized with a soldier on one side and the soldier’s wife and three children on the other, praying for his safe return. Why do they belong in this scene? Some wartime artists drew parallels between Christ and the soldiers’ sacrificial laying down of their lives (cf. John 15:13). I’m uneasy with this comparison for several reasons, not least of which is my Christian pacifism. But de Wit’s painting seems, rather, to use the soldier and his family as a representation of war and to suggest that Jesus, the Suffering Servant, is with us in our present suffering. He entered our world, after all, and died to redeem us from its evils—sin and death and all their extensions. The presence of Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows, must have been a comfort to the mothers at Sacred Heart whose sons were overseas fighting.

Moreover, even though its hieratic style may be off-putting to some, I also really like the crucifix de Wit created for Sacred Heart (but which is now at St. Paul the Apostle Catholic Church, also in Baton Rouge). The corpus is painted on solid mahogany, with real nails driven through the hands. Continue reading “The Art of Dom Gregory de Wit”