(This post is optimized for viewing in a web browser on a computer screen.)

The pelican was one of the most popular animal symbols for Christ in the Middle Ages, appearing widely in art and literature. The association was first made in the Physiologus, a Late Antique Greek compilation of moralized animal lore written (probably around the year 200) in Alexandria and intended for Christian edification. Its anonymous author says the mother pelican is such “an exceeding lover of its young” that, to revive them from death, she pierces her breast with her beak and spills her blood over them.

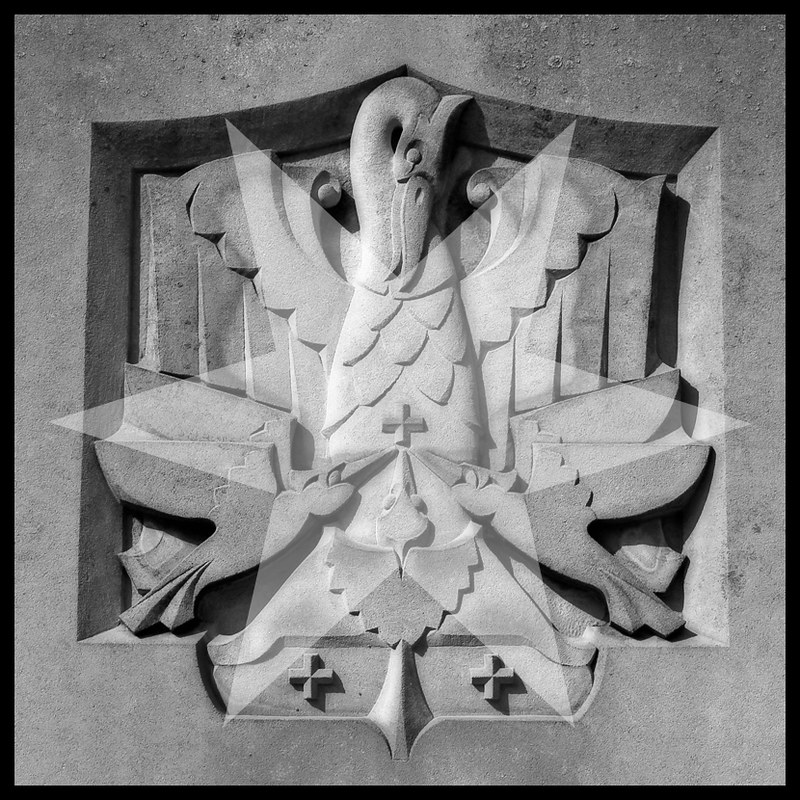

The church sometimes refers to this allegorical bird as the vulning pelican (from the Latin vulnerō, “to wound”), or the Pelican in Her Piety.

The Christological parallel is obvious: Jesus submitted to being pierced with nails and spear on the cross, his heart’s blood spilt, in order to give life to his children. But the Physiologus cites a more obscure biblical passage: “ὡμοιώθην πελεκᾶνι ἐρημικῷ” (Ps. 101:7a LXX). In the Latin Vulgate, that’s “Similis factus sum pelicano solitudinis,” and in English, “I am like a pelican of the wilderness” (Ps. 102:6a KJV). The Physiologus author puts these words of the psalmist, which express a sense of isolation, into the mouth of Christ, lonely in his messianic ministry and in his passion.

Not all parts of the pelican legend recounted in the Physiologus map easily onto Christ’s love for his church. The chicks are dead because they kept striking their parents in the face, and their parents, striking back, killed them. The parents feel bad, and it’s after three days of mourning that mama bird breaks herself open to bring back her little ones.

In his commentary on Psalm 102, Augustine writes, “Let us not pass over what is said, or even read, of this bird, that is, the pelican.” Standing over her dead chicks, “the mother wounds herself deeply, and pours forth her blood over her young, bathed in which they recover life. This may be true, it may be false: yet if it be true, see how it agrees with him, who gave us life by his blood. It agrees with him in that the mother’s flesh recalls to life her young with her blood; it agrees well. For he calls himself a hen brooding over her young. If, then, it be so truly, this bird does closely resemble the flesh of Christ, by whose blood we have been called to life.”

Augustine then goes on to explain how the mother’s killing her young relates to God metaphorically killing our old self so that he can then raise us up to new life in Christ; he likens conversion to death and rebirth. Medieval theologians loved to stretch allegories to the extreme!

A more streamlined version of the pelican legend that got passed down omits the filicide, focusing simply on the bird’s animating sacrifice—on how her shed blood raises the dead to life. And after the Feast of Corpus Christi was established in 1311, a variant emerged that said the pelican feeds her young with her blood when no other food would satisfy, a picture that resonated with the increased attention on the Eucharist in the Latin West.

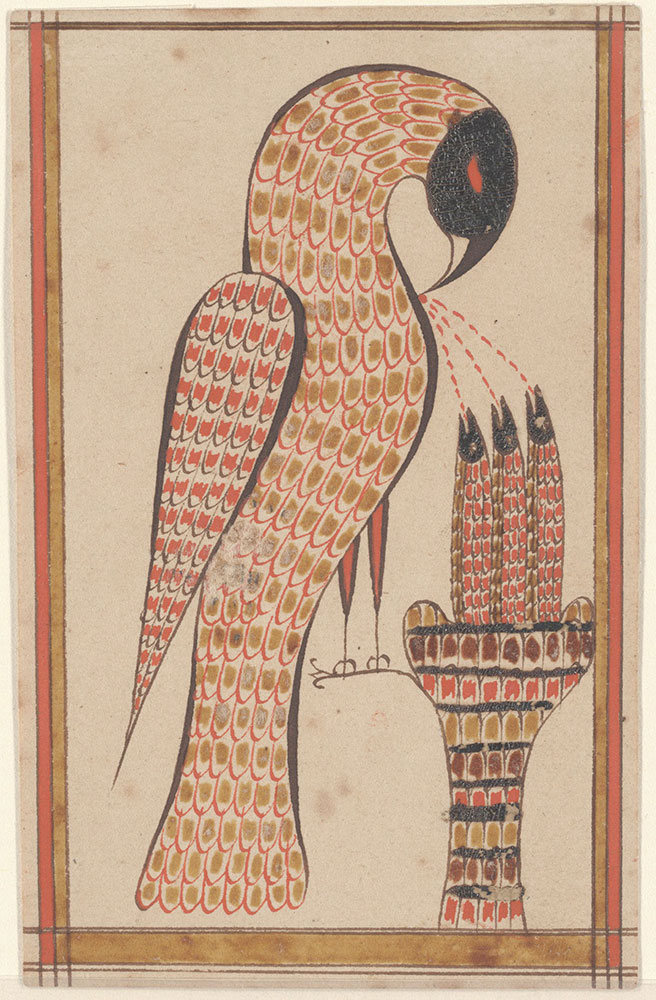

The Physiologus, which contains the earliest known appearance of the pelican legend, was translated from Greek into Latin sometime between the fourth and early sixth centuries, and from there into Ethiopic, Armenian, Syriac, and a multitude of European and Middle Eastern vernaculars. By the end of the twelfth century its legends were absorbed into the bestiary, a genre of popular nature-book in keeping with the encyclopedic taste of the High Middle Ages.

In Art

The vulning pelican has appeared in all kinds of visual media from late antiquity through the medieval and premodern eras and on into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, including illuminated prayerbooks, missals, bestiaries (as in the tiled gallery below; hover to view captions, or click to enter carousel); panel paintings, frescoes; mosaics; stained glass windows; tapestries; lecterns, roof bosses, bench ends, misericords, corbels; and a range of liturgical objects and vestments.

The bird doesn’t always look like an actual pelican, though. It could be that some of the artists had never seen one, although the Dalmatian pelican, which has the long bill and the expandable throat pouch that we most associate with the genus, had been widespread across Europe since ancient times. More likely, the imaginative rendering of the pelican in Christian art derives from the account of the bird in book 12 (“De animalibus”) of the widely influential compendium Etymologies by the Spanish archbishop Isidore of Seville, written around 623, which repeats the popular legend and adds that the pelican lives in Egypt. An exotic bird therefore required exotic treatment.

Neither does the behavior the Physiologus ascribes to pelicans have any basis in natural fact. It’s possible the legend arose from the observation that the pelican sometimes bends its beak into its chest, which may look like it’s piercing it, and that some pelicans have a reddish tinge on their breast plumage and/or a red tip on their beak. However, zoological accuracy was not the point; the point was to convey theological truth.

In The Bestiary of Christ, Louis Charbonneau-Lassay says the pelican first started appearing as a Christian symbol on clay oil lamps in ancient Carthage (present-day Tunisia), citing “L. Delattre, Carthage, Symboles eucharistiques, p. 91”—the French archaeologist Alfred Louis Delattre (1850–1932). But I’ve not been able to track down the cited text or find any such examples. If you can point me to photographs, please do!

In the “Ējmiacin [Etchmiadzin] Codex” entry in The Eerdmans Encyclopedia of Early Christian Art and Archaeology, Paul Corbey Finney identifies the border illustrations in that Armenian Gospel book’s Baptism of Christ miniature from ca. 600 as depicting a pink-bodied pelican spreading its blue wings and pecking its breast while standing in a bejeweled chalice. The figure is repeated ten times.

Finney mentions that a vulning pelican also appears in the Rabbula Gospels from sixth-century Syria. I think he’s referring to the bird at the top of the canon tables on folio 5a, which also shows the prophets Joel and Hosea and the Wedding at Cana. The iconography is far less obvious here.

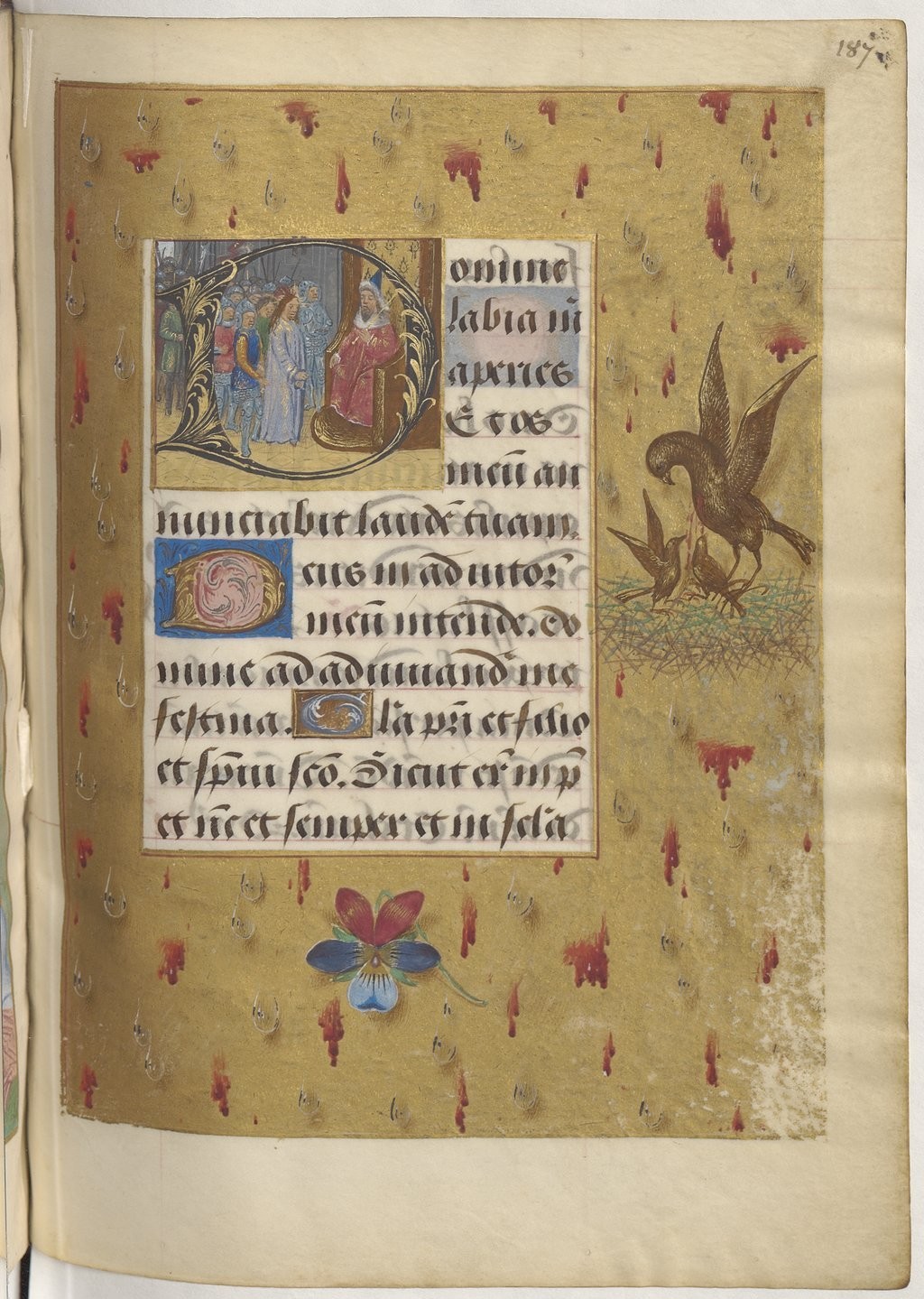

One illuminated manuscript page I love that makes use of the pelican symbol comes from the late Flemish Boussu Hours, a prayerbook made for Isabelle de Lalaing, probably after the death of her husband Pierre de Hennin, lord of Boussu.

Appearing opposite a full-page miniature of Christ in Gethsemane, folio 187r opens the Hours of the Passion prayer cycle:

V: Domine labia mea aperies.

R: Et os meum annunciabit laudem tuam.

V: Deus in adiutorium meum intende.

R: Domine ad adiuvandum me festina.

Gloria Patri, et Filio: et Spiritui sancto.

Sicut erat in principio, et nunc, et semper: et in saecula saeculorum.English translation:

V: O Lord, open my lips,

R: And my mouth shall declare thy praise.

V: Incline unto my aid, O God.

R: O Lord, make haste to help me.

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost,

as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be: world without end.

The historiated initial “D” shows Christ before Pilate, and in the margin a pelican exudes her lifeblood into the mouths of her two chicks, a scene set against a gold background likewise dripping with blood—as well as sweat and tears. It’s “almost as if the gold margin were an expanded microcosm of the bird’s broken breast,” writes Katharine Davidson Bekker in her essay “Those Who Weep: Tears, Eyes, and Blood in the Boussu Hours.” Bekker further notes that “the pansy flower in the margin, the name of which references the French penser (‘to think’), . . . encourages the reader to think deeply about the images on the page.”

Another remarkable appearance of the pelican in medieval manuscript illumination is in the Holkham Bible Picture Book from fourteenth-century England—remarkable because it appears not in a passion cycle, as was typical, but in a creation cycle!

In the garden of Eden, God the Creator, portrayed here as Christ, instructs Adam and Eve that they may freely eat of any tree except the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, which he points to with one hand and with the other wags his finger in a forbidding manner. Various birds perch atop the adjacent trees, but at the apex of this fateful one at the center is the vulning pelican, foreshadowing the sacrifice of Christ that will be required for humanity to reenter Paradise after the fall.

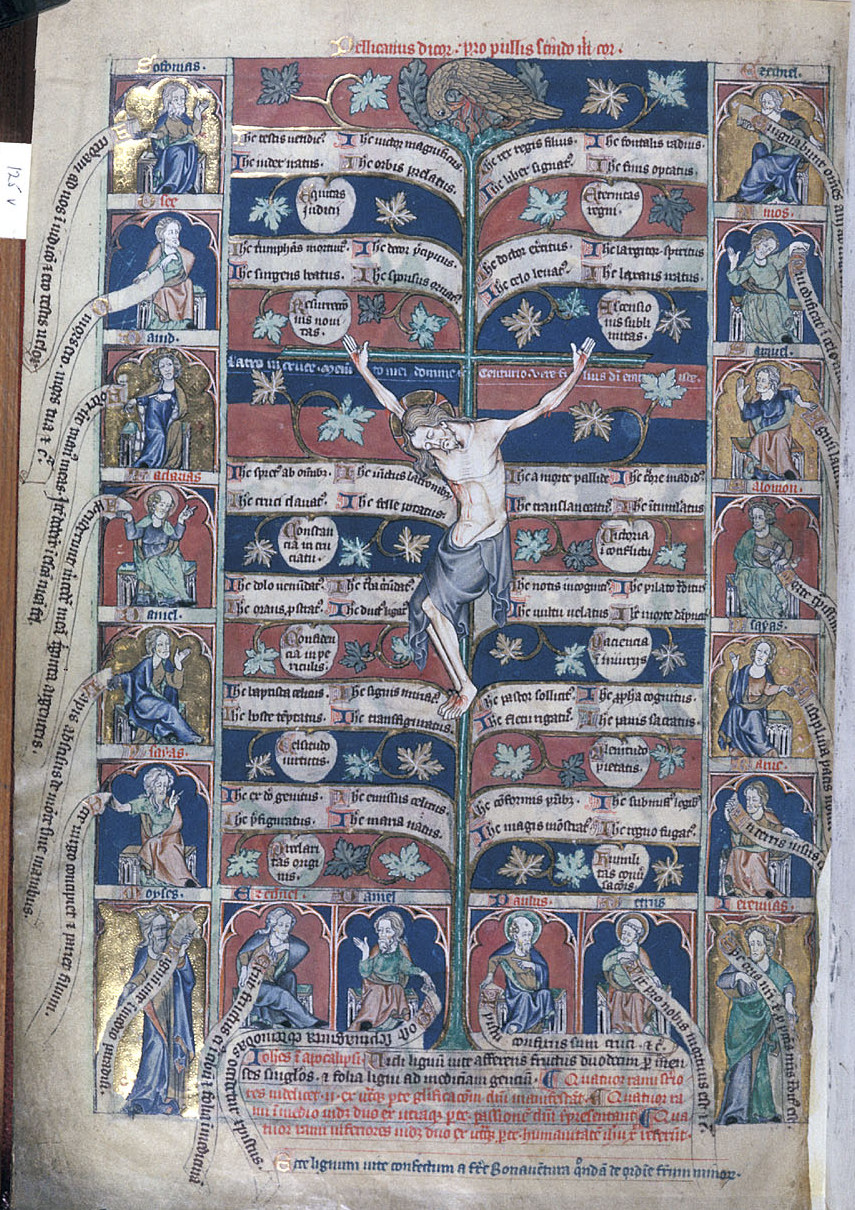

Compare this image to the diagrammatic one on folio 125v of the De Lisle Psalter, which was inspired by Bonaventure’s meditational treatise the Lignum vitae. It shows a pelican nesting atop the tree of life on which Christ is crucified, wounding herself to feed her offspring with her blood:

The Latin inscription above it in red reads, Pellicanus dicor, pro pullis scindo mihi cor (“I am called a pelican, because I tear open my heart for my chicks”). The twelve branches contain texts relating to Christ’s humanity, passion, and glorification, while the surrounding panels contain Old Testament witnesses.

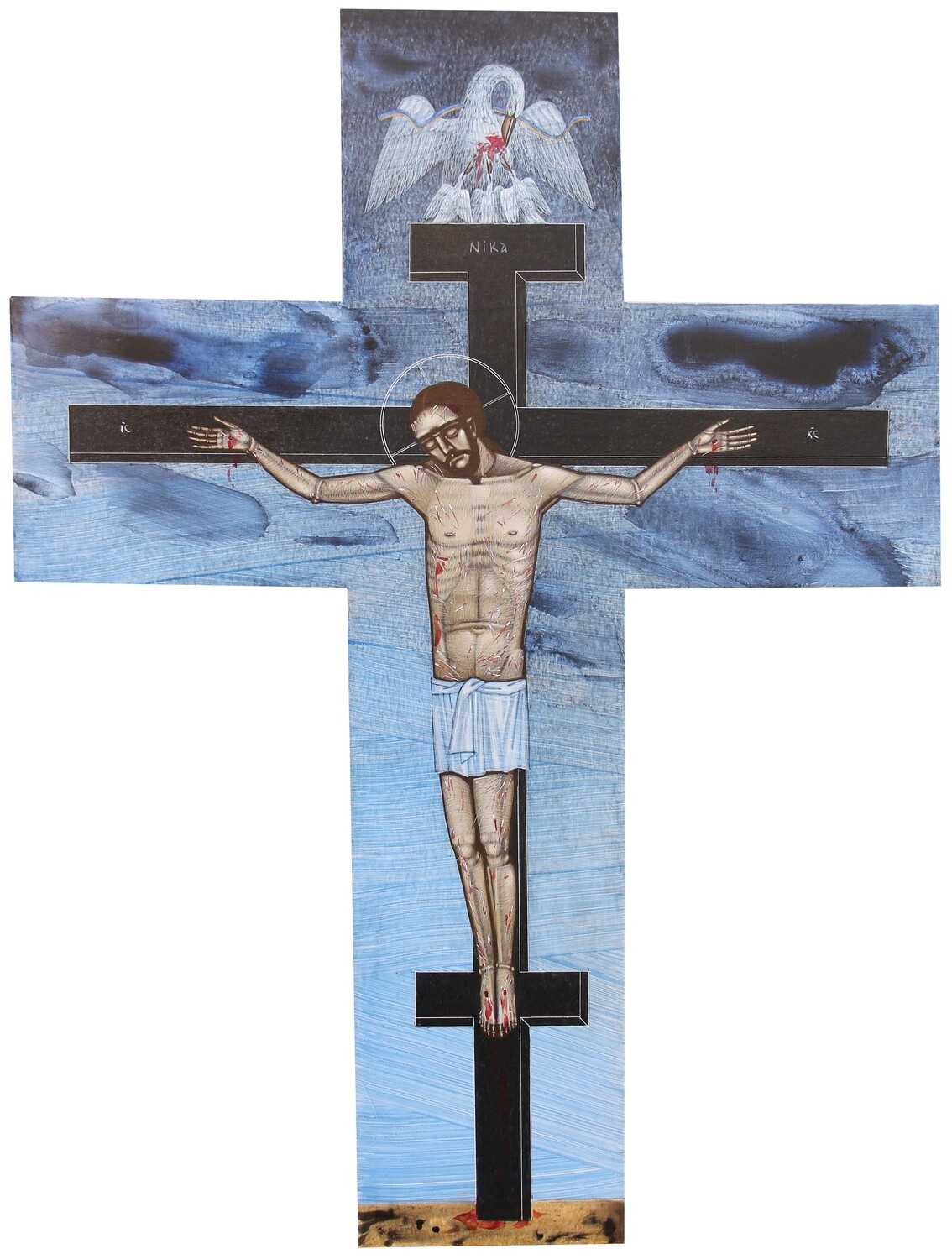

The Crucifixion is the narrative context in which the vulning pelican most often appears in art, reinforcing the notion of Christ’s self-emptying sacrifice. It was especially popular in proto- and early Renaissance panel paintings from Italy—which the gallery below reflects, in addition to featuring a few other examples from France, Greece, and Armenia.

In the Simone di Filippo Benvenuti example above (third row, left), notice the little winged dragon fleeing the pelicans’ nest as the mother pelican undoes the harm he has inflicted. A similar detail can be found in the Crucifixion fresco from the altar wall of the Oratory of St. John the Baptist in Urbino, which shows a snake slithering away from the perishing chicks, who are brought back to life by their intervening mother:

The snake motif references a version of the pelican legend found in De natura rerum (On the Nature of Things) by the Flemish Dominican friar Thomas of Cantimpré (ca. 1200–1272) and the slightly later De animalibus (On Animals) by the German Dominican friar Albertus Magnus (ca. 1200–1280). According to these two works, when the mother pelican leaves her nest to find food for her fledglings, she returns to find them dead from the bite of an ambushing snake. She then tears her own flesh to revive them with her blood, which is full of healing properties.

One of the most unique visual treatments of the vulning pelican that I found is a painting by the Dutch Renaissance artist Hieronymus Bosch. Rendered in grisaille (gray monochrome), his pelican appears in the center of a ring depicting scenes from the passion of Christ. It’s painted on the reverse of a panel that shows John the Evangelist in exile on Patmos, penning the book of Revelation.

Staged around mountain crags, the passion cycle begins on the right with Jesus praying in Gethsemane and continues clockwise with the Arrest of Christ, Christ before Pilate, the Flagellation, the Crowning with Thorns, the Carrying of the Cross, the Crucifixion, and the Entombment.

Outside this ring of scenes is a darkness populated by shadowy demons:

But the inner disc, the focal point of the composition, contains the promise of redemption. Emerging from the still waters of a vast postdiluvian landscape is a hillock with a hollow that houses a burning fire. On the summit, a large mother bird spreads her protective wings over her brood, inclining her head toward her chest—an iconography we recognize as the vulning pelican, symbolic of the deep, saving love God embodied on the cross.

As we view this painting, we progress from the outer darkness with its infernal powers, to the growing light actualized by the events of Maundy Thursday and Good Friday, and finally to the brilliant center with its red flame—which, other than two dim, flickering torches in Gethsemane, contains the sole bit of color in the whole painting. Images of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which would gain prominence in the seventeenth century, feature a flame, representing Christ’s ardent love burning bright. And that’s what we have here.

Red is also the color of blood. I’m reminded of Robert Southwell’s poem “Christ’s Bloody Sweat,” which combines imagery of the pelican and the self-immolating but ultimately indestructible phoenix, marveling at “how bleedeth burning love.” (I’ll explore a few more poems about the pelican in the next section.)

As John writes in the wonderful prologue to his Gospel, “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overtake it” (John 1:5).

In Bosch’s painting, the Christbrand bursts, like the pelican’s split side. The flame of redemption is lit, like a lighthouse, calling us home into the love of God.

Another especially compelling art object that draws on the pelican legend is a silver-plated tabernacle monstrance from Portuguese Goa in southwestern India.

In the Roman Catholic Church, a tabernacle is a container in which the consecrated hosts (small unleavened wafers of bread) of the Eucharist are stored as part of the “reserved sacrament” rite, and a monstrance is a vessel that displays the consecrated host on the altar and in procession. This object combines both into one—the spherical base serving as the tabernacle, with access gained through an opening at the back, and the bird’s breast bearing a transparent aperture surrounded by a golden sunburst halo, through which the host can be viewed. The body of Christ, broken for you.

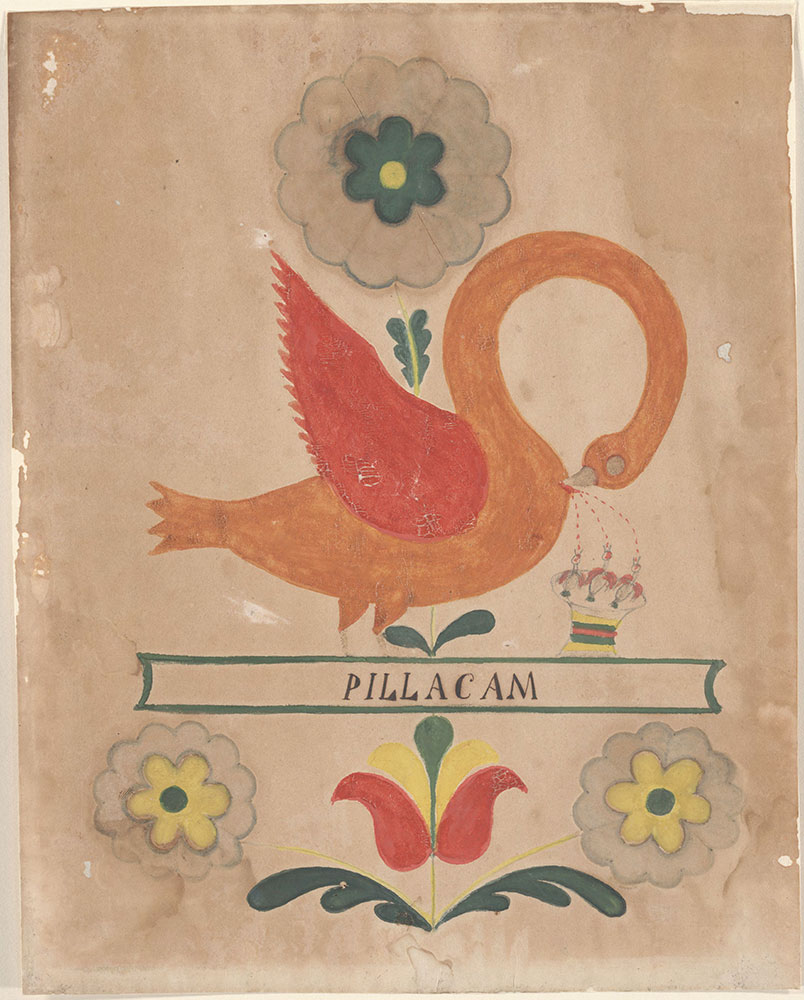

In researching this essay, I found that the pelican is a subject that recurs (so charmingly!) in the folk art of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Pennsylvania Germans:

From the Victorian era, I’m especially fond of the stained glass pelican design by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones, fabricated by Morris & Co. to serve as part of the East Window of St Martin’s Church, Brampton, in Cumbria. Burne-Jones drew his design in 1880, and after the window was completed the following year, he returned to the drawing out of personal fondness, embellishing it with colored chalks, and gold for the blood drops, thus developing it into a more substantial work.

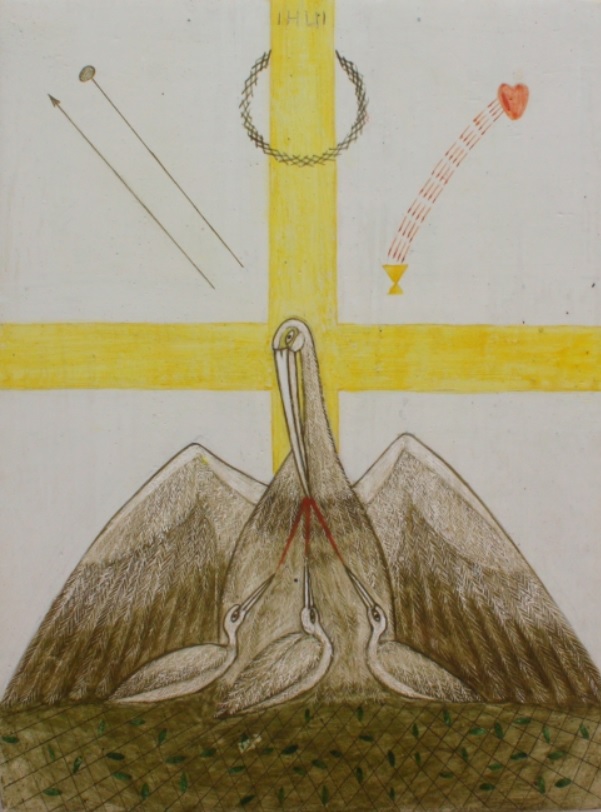

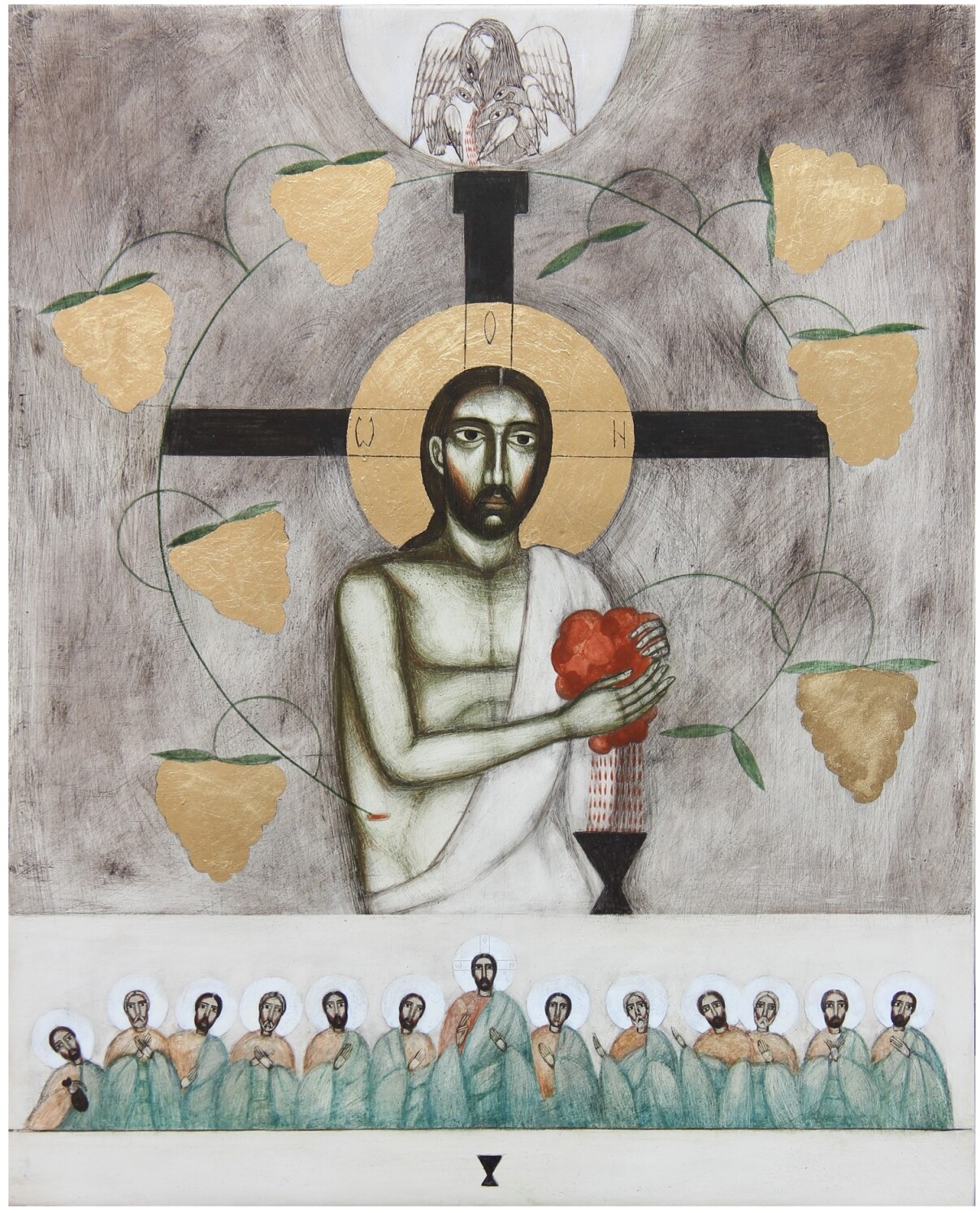

Contemporary artists have also turned to the subject of the vulning pelican, especially the Ukrainian Catholic women iconographers of Lviv:

Addendum, 4/8/25: Shortly after publishing this, a reader reminded me of Josh Tiessen’s painting All Creatures Lament from his Vanitas and Viriditas series, which shows an American white pelican protecting her chicks in the face of another oil spill and the accumulation of fishing-related plastic waste. Tiessen, an artist of faith, directs the symbolism of the pelican toward a call for wildlife conservation. (I previously featured Tiessen’s work here.)

In Poetry and Song

Probably the most universally famous poetic treatment of the pelican as an emblem of Christ is the eucharistic hymn “Adoro te devote” (Hidden God, Devoutly I Adore Thee). Written around 1260 by Thomas Aquinas, it is one of the most beautiful medieval poems in Latin. Aquinas did not originally write it for the liturgy, but it was added to the Roman Missal in 1570 and since then has been used in the Catholic Mass. The penultimate stanza reads:

Pie pelicane, Jesu Domine,

Me immundum munda tuo sanguine,

Cujus una stilla salvum facere

Totum mundum quit ab omni scelere.

Like what tender tales tell of the Pelican,

Bathe me, Jesus Lord, in what thy bosom ran—

Blood that but one drop of has the pow’r to win

All the world forgiveness of its world of sin.

Trans. Gerard Manley Hopkins

Here’s a great video of the hymn put out by the Fundación Canto Católico, set to a Benedictine plainsong melody from the thirteenth century, as has become standard. Our pelican passage appears at the 4:10 mark. The subtitles are in Spanish, but you can turn on CC for English.

(If, like me, you’re wondering what in the world the video’s images are from, an explanatory note in the YouTube comments section explains: they are from the Cuasimodo festival in Chile, celebrated the second Sunday of Easter. The festival has nothing to do with Victor Hugo’s famous hunchback but rather is about bringing Communion to the sick and elderly who were unable to leave their residences to participate in the sacrament during Holy Week. [The Spanish Cuasimodo comes from the Latin Quasimodo, from the incipit of the day’s introit based on 1 Peter 2:2: “Quasi modo géniti infántes . . . ,” or “As newborn babes . . .”] Traditionally for this task, priests were escorted by horsemen, who showed them the route and protected them from assaults.)

The vulning pelican also appears in the liturgy of the Eastern Orthodox Church, whose members sing at Matins on Good Friday evening, “Like a pelican wounding her breast, Thou, O Word, hast made Thy mortal children to live, for Thou hast shed upon them life-giving streams.”

Dante Alighieri, the great medieval Italian writer, calls Christ “nostro Pelicano” (our Pelican) in canto 25 of his Paradiso, the third book in his Divine Comedy trilogy of extended narrative poems.

The Christ-pelican appears, too, in English poetry from the late Middle Ages onward. One Middle English poem found in a prayerbook from ca. 1460 reads:

The pellicane his bloode dothe blede

Therwith his birdis for to fede.

It figureth that God with his bloode

Us fede hanging on the rode,

Whane he us brought oute of hell

In joy and blis with him to dwel,

And be oure fader and oure fode,

And we his childerne meke and good.

[Bodleian Library MS Douce 1, fol. 57r]

The pelican his blood doth bleed,

Therewith his birdies for to feed.

It figures God, who, with his blood,

Fed us hanging on the rood,

By which he brought us out of hell,

In joy and bliss with him to dwell,

To be our father and our food,

And we his children meek and good.

A more sophisticated verse treatment of this idea can be found in A Collection of Emblems, Ancient and Modern by George Wither, published in London in 1635:

Our Pelican, by bleeding thus,

Fulfill’d the law, and cured us.Look here, and mark (her sickly birds to feed)

How freely this kind Pelican doth bleed.

See how (when other salves could not be found)

To cure their sorrows, she herself doth wound;

And when this holy emblem thou shalt see,

Lift up thy soul to him, who died for thee.For this our hieroglyphic would express

That Pelican which, in the wilderness

Of this vast world, was left (as all alone)

Our miserable nature to bemoan;

And in whose eyes the tears of pity stood,

When he beheld his own unthankful brood

His favors and his mercies then condemn,

When with his wings he would have brooded them,

And sought their endless peace to have confirm’d,

Though to procure his ruin, they were arm’d.To be their food, himself he freely gave;

His heart was pierc’d, that he their souls might save,

Because they disobey’d the sacred will,

He did the law of righteousness fulfill;

And to that end (though guiltless he had been)

Was offered for our universal sin.Let me, oh God! forever fix mine eyes

Upon the merit of that sacrifice:

Let me retain a due commemoration

Of those dear mercies, and that bloody passion,

Which here is meant; and by true faith, still feed

Upon the drops this Pelican did bleed;

Yea, let me firm unto thy law abide,

And ever love that flock for which he died.

I already mentioned, in relation to Bosch’s pelican painting above, “Christ’s Bloody Sweat” by the English Catholic martyr Robert Southwell.

More recently, the Anglican priest Matt Simpkins, who performs music under the name Rev Simpkins, wrote a song titled “Pelican,” which he released on his album Big Sea (2020). Gritty and impassioned, here’s a live performance at Colchester Arts Centre:

Pelican feeds the hungry and needy

I kneel before her

My throat like an open graveFood cannot fill me

Water dilutes me

Nothing contents me

Pelican, pity meShe tears her breast, her children to refresh

By her I am blessed, led to life from living deathThough death entreats me

Her life flows sweetly

Given so freely

Given in flesh and bloodShe tears her breast, her children to refresh

By her I am blessed, led to life from living deathPelican feeds me

Loves me completely

Though I’m unworthy

She gives so graciouslyShe tears her breast, her children to refresh

By her I am blessed, led to life from living deathShe crowns the whole earth, the heavens and seas

The Pelican tears her breast for meShe’s queen of what was and what is to be

The Pelican tears her breast for meShe gives of herself in infinity

The Pelican tears her breast for meShe’s compassion and love, she’s strength and glory

The Pelican tears her breast for me

I love it when contemporary artists engage with historical Christological symbols, whether from the animal world or elsewhere, tapping into a creative wisdom the saints of ages past have bequeathed to us but that is too often dismissed in favor of literalism or wordy, intellectual articulations of doctrine.

I wholeheartedly support the endeavor of academic theology, but it must be remembered that for centuries, the church has developed her theology not just through discursive prose but also through liturgy, verse, and visual art. While many modern Christians may discount medieval allegories of Christ as naive, backward, too fanciful, or too obscure, I want to suggest that there’s value in learning (at least some of) them and even incorporating them into new material, to explore how they might come alive in new contexts.

By studying the pelican of ancient lore, for example, as it has been adapted in Christian art and literature, I’ve grown in my appreciation for the mother-love of God, who, to restore me to life and to nourish me—his child, his dependent—allowed his sacred flesh to be torn, so that I might know the power in the blood.

This essay took many hours to research and write and came to fruition only after several years spent collecting enough Pelican images to reach a critical mass. If you have the inclination and means to support more essays like this, I’d really appreciate a donation!