CHRISTMAS EVE SERVICE 2021, Good Shepherd New York: Good Shepherd New York is an interdenominational church located in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan. When the pandemic hit in 2020, like many churches, they pivoted to online services. This video-only format enabled them to expand their music ministry, soliciting participation from nonlocal musicians, who collaborated virtually with the church’s in-house musicians to release some stellar worship music—beautiful arrangements and performances. While GSNY now meets again in person for worship, they also release separate digital worship services on their YouTube channel to reach a wider community. Last year I tuned in to their Christmas Eve service, which I really enjoyed, particularly the music. “Mary’s Lullaby,” written by associate pastor David Gungor and sung by his wife, Kate, with harmonizing vocals by Liz Vice, is my favorite from the list.

- Children’s skit

- 4:31: Prelude: “Carol of the Bells,” cello solo by David Campbell

- 5:20: Welcome

- 7:22: “Mary, Did You Know,” feat. Charles Jones

- 11:04: “O Come, All Ye Faithful”

- 13:55: “Joy to the World!”

- 16:55: “Angels We Have Heard on High”

- 20:51: “Hark! the Herald Angels Sing”

- 23:51: “O Holy Night,” feat. Charles Jones

- 28:05: “Mary’s Lullaby” (by The Brilliance), feat. Kate Gungor and Liz Vice

- 30:03: Sermon by Michael Redzina

- 44:55: “Silent Night,” feat. Matthew Wright and Liz Vice

- 48:43: “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” (by John Lennon)

Many of these songs were released last month on the Good Shepherd Collective’s debut Christmas album, Christmas, Vol. 01, available wherever music is sold or streamed.

Good Shepherd New York will be holding an in-person candlelight service at 5 p.m. on Christmas Eve this year in the Chapel of the Good Shepherd at 440 West 21st Street. Musician Charles Jones will be there.

+++

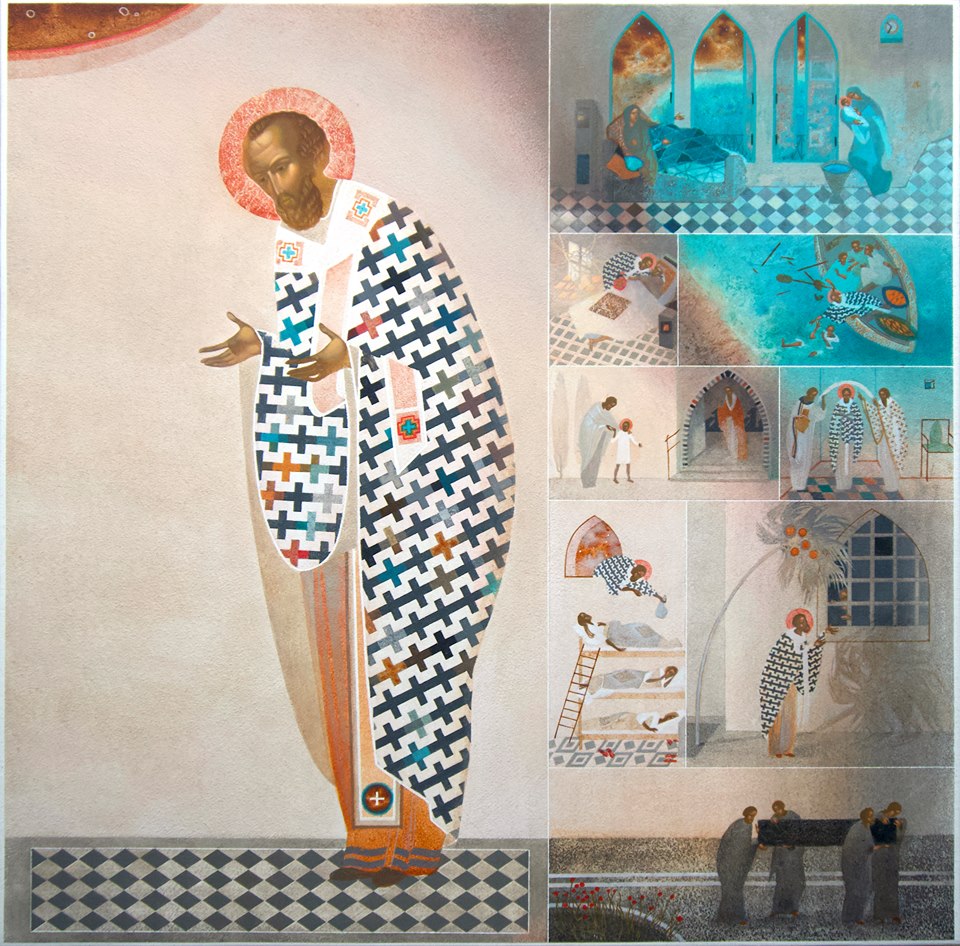

EXHIBITION WALK-THROUGH: Słowo stało się Ciałem (The Word Became Flesh), Warsaw Archdiocese Museum, March 3–31, 2021: Last year a collection of contemporary Ukrainian and Polish icons on the theme of Incarnation was exhibited in Warsaw. In this video, curator Mateusz Sora and Dr. Katarzyna Jakubowska-Krawczyk, head of the Department of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Warsaw, discuss some of the pieces. I don’t speak a lick of Polish, and closed captioning is not available, so I’m not sure what is said—but the camera gives a good visual overview. You can also view a full list of artists and photos of select icons in this Facebook post.

ON A RELATED NOTE: There’s a public exhibition of icons by several of these artists happening in North Carolina at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary–Charlotte through February 17, 2023: East Meets West: Women Icon Makers of Western Ukraine. I attended an earlier iteration of East Meets West in Massachusetts back in 2017 (mentioned here), and it was wonderful. The icons are owned by the American collector and former news correspondent to the USSR John A. Kohan, and he has added more pieces to this area of his collection since I last saw it.

There will be a special event on Wednesday, February 1, from 7 to 9 p.m., featuring a talk about the history of iconography by Professor Douglas Fairbairn and a video introduction by Kohan; RSVP here.

+++

ICON INTERPRETATION: “The ‘All-Seeing Eye of God’ Icon” by David Coomler: Icons expert David Coomler unpacks a preeminent example, and two variants, of this unusual icon type that emerged in Russia at the end of the eighteenth century, influenced by the “Eye of Providence” symbol found, for example, on the Great Seal of the United States. Moving from the center outward, four concentric circles show a young Christ Emmanuel, a sun-face, the Theotokos (Virgin Mary), and the angelic hosts, with Lord Sabaoth (God the Father) at the top and symbols of the Four Evangelists at the corners. Inscriptions include “As the burning coal that appeared to Isaiah, a sun arose from the virgin’s womb, bringing to those who wandered in darkness the light of the knowledge of God” (a variant of the Irmos, Tone 2, from the Easter Octoechos) and “My eyes [shall be] on the faithful of the land, that they may dwell with me” (Psalm 101:6).

For more icons of this type, see Dr. Sharon R. Hanson’s Pinterest board. And for a fascinating history of the disembodied eye–in-triangle that’s most often associated (unwarrantedly) with Freemasonry in the popular imagination, read Matthew Wilson’s BBC article “The Eye of Providence: The symbol with a secret meaning?” (I learned that one of its earliest appearances is in a Supper at Emmaus painting by Pontormo! It was a Counter-Reformation addition, to cover up the newly banned trifacial Trinity that Pontormo had painted.)

+++

SONG: “Almajdu Laka” (Glory to You) (cover) by the Sakhnini Brothers: The Sakhnini family has lived in Nazareth—Jesus’s hometown!—for generations and is part of the town’s minority Arab Christian population. Adeeb, Elia, and Yazeed Sakhnini [previously] record traditional and original Arabic worship songs together as the Sakhnini Brothers. This is their latest YouTube release, just in time for Christmas. The song is by the Lebanese composer Ziad Rahbani. Turn on “CC” to view the lyrics in English, and see the full list of performers in the video description.

+++

BLOG SERIES: Twelve Days of Carols by Eleanor Parker: There’s a plethora of medieval English Christmas carols preserved for us in medieval manuscripts, a few of which are still part of the repertoire around the world but most of which have fallen into disuse or that are at least lesser known. Medievalist Eleanor Parker spotlights twelve from the latter category. She ran this series back in 2012–13 with the intention of doing twelve posts, one for each day of Christmas, but she stopped short at seven—so I’ve added links to additional carol-based posts of hers from other years. She provides modern translations of the Middle English and, in some cases, brief commentary.

Note that #11 contains an Old English word that Tolkien adopted in his Lord of the Rings!

- “Welcome, Yule” (below)

- “The Sun of Grace”

- “Come kiss thy mother, dear”

- “A Becket Carol”

- “The Jolly Shepherd”

- “Be Merry, and the Old Year”

- “Behold and See”

- “Hand by hand we shall us take”

- “King Herod and the Cock” (below)

- “Be merry, all that be present”

- “Hail Earendel”

- “Christmas Bids Farewell”