One of the delightful surprises of my recent trip to Germany and Belgium was to find, in two of the museums I visited, an integration of the old and new in the curated galleries. Typically, art museums choose to arrange their collections chronologically, grouping together artworks from a particular era, and within each era, like styles. But in Kolumba museum in Cologne and the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen (KMSKA) in Antwerp, medieval art from each museum’s collection (and in the case of KMSKA, Renaissance and Baroque art too) is displayed alongside contemporary pieces, creating a vibrant dialogue.

With the exception of the exterior shot of Kolumba, all photos in this post are my own.

Kolumba Kunstmuseum, Cologne

Originally called the Diözesanmuseum (Diocesan Museum), Kolumba was founded in 1853 by the fledgling Christlicher Kunstverein für das Erzbisthum Köln (Christian Art Association for the Archbishopric of Cologne), making it the city’s second oldest museum after the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum. Its collection focus for the majority of its history was late medieval art from Cologne and the Lower Rhine.

Kolumba’s first permanent home, just south of Cologne Cathedral, was a former sugar factory, but the building was destroyed in World War II, though much of the art had been safely evacuated beforehand. After the war, Kolumba relocated its art to a grammar school, then to rented rooms in the Gereonstraße, then to the Curia building at Roncalliplatz 2. But the limited space was an issue.

In 1989, ownership of the museum was transferred to the Archdiocese of Cologne, who decided to expand the collection to include modern and contemporary art, not only by German artists but by international artists as well. The museum shifted its approach from displaying traditional sacred works only, to placing those works in juxtaposition with newer ones by artists who aren’t necessarily Christian but whose works can converse fruitfully with their core collection. They also secured funding to construct a new permanent building.

In 2004, the museum’s name was changed to Kolumba in honor of the history of the site on which the new (and current) building would stand: atop the ruins of the medieval St. Kolumba church, destroyed in an air raid in 1943. St. Columba of Sens was a third-century virgin martyr who was born in Spain but lived mostly in France. The church dedicated to her in Cologne once housed Rogier van der Weyden’s St. Columba Altarpiece (now at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich), a triptych with scenes of the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Magi, and the Presentation in the Temple.

Kolumba museum’s permanent home opened in 2007 at Kolumbastraße 4. Designed by the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor (view more architectural photos here), the building encapsulates the bombed-out Gothic ruins of St. Kolumba with forty-foot-high, porous concrete walls, above which sit the floors of the museum.

It also incorporates the Madonna in den Trümmern (Madonna in the Ruins) chapel, an octagonal tent-like structure built by Gottfried Böhm in 1947–50 to house a late Gothic statue of the Madonna and Child that miraculously survived the Allied bombings and for the liturgical use of the small Kolumba parish, which continues today.

The postwar chapel is not accessible from inside the museum; it has its own separate entrance, which, as I found out after I had already left, is on the south side of the building, along Brückenstraße.

But I did cross over the excavation site of St. Kolumba to which the written museum guide directs visitors (it’s labeled “room 3”), and through which a walkway has been constructed. As I took in the war-wrought devastation, I wondered about the sounds I was hearing from an audio system. Turns out it was a sound installation called Pigeon Soundings by the American artist Bill Fontana. In 1994, he made a series of eight-channel sound map recordings of the pigeons that were inhabiting the St. Kolumba ruins at the time, particularly the rafters of the temporary wooden roof that had been erected. The recordings picked up not just the birds’ cooing and flapping, but also the ambient sounds outside.

Above this darkened space, Kolumba has sixteen exhibition rooms. The museum reinstalls its collection annually, each fall opening a new exhibition. I was there for the first day of “make the secrets productive!” Art in Times of Unreason, which runs from September 15, 2025, to August 14, 2026. The lack of art signage throughout is deliberate, to promote a more meditative experience; instead, visitors are given a (German-language) booklet, organized by room, that identifies the pieces on display and provides commentary for some.

Room 8 features a fifteenth-century sculpture of Christ at Rest—“at rest” not in the sense of being at peace in mind or spirit (he is visibly troubled), but rather in a bodily state of motionlessness or inactivity. Sometimes also called Christ in Distress, Christ on the Cold Stone, or Pensive Christ, the iconography shows an interior moment during Christ’s passion in which, having just been flogged, he sits awaiting his final torture: crucifixion.

Though the Gospels don’t mention a moment of seated pause in the narrative, artists were influenced by the figure of Job, an innocent sufferer who in that way prefigured Christ, and in particular the description in Job 2:8 of him sitting on a dung heap. The image of Jesus preparing to meet his death was meant to inspire feelings of pity. Isolated from the action and from all the other characters, the lone figure invites viewers to enter empathetically into the emotional anguish he suffered on his way to the cross.

At Kolumba, this sculpture is surrounded by large-scale, black-and-white photographs from the Transzendentaler Konstruktivismus (Transcendental Constructivism) series by the collaborative duo of German neo-dadaist artists Anna and Bernhard Blume. In the series the couple is threatened by white geometric objects that are unleashed on them in a blur of motion.

The diptych that hangs behind the Christ sculpture appears to show a man carrying a cross, disoriented by its weight.

One of the other resonant pairings at Kolumba is in room 21, which stages a fifteenth-century Ecce homo sculpture across from a colored chalk drawing on a three-paneled blackboard.

The title Ecce homo, Latin for “Behold the man,” comes from John 19:5, where the Roman governor Pilate presents a scourged, thorn-crowned Jesus to a mob that demands his execution. Like Christ on the Cold Stone, this too is a devotional image intended to stir the affections of the viewer, who is called, like the crowds on that fateful day, to gaze upon the wounded God-man. His hands are bound in front of him, evoking a sacrificial sheep tied up for slaughter. What have we done?

While I instantly recognized this subject, the drawing was more of a mystery.

Not having any wall text to clue me in, I had to simply observe and intuit. I saw a winding chute, rainbow-colored, with a few white feathers sticking out of it. And is that water in the background?

I noticed, too, that it’s a triptych, a common format for altarpieces.

Water, birds, rainbows—those all play into the story of Noah’s flood, in which the rainbow signifies God’s promise to never again destroy the earth and all its inhabitants. It’s a symbol of grace and reconciliation.

There are also two prophetic texts in scripture that associate the rainbow with Christ and his glory: Ezekiel’s and John’s recorded visions of the divine throne (Ezek. 1:28; Rev. 4:3).

The curator has positioned Jesus facing the rainbow road, across a fairly large gap. Since, as the museum states, the artworks are arranged to interpret each other, at least in part, then it’s possible this room conveys Jesus following the path of promise, even as it takes dark turns. Or choosing to endure the judgment of the cross to secure a glorious inheritance for his beloveds.

After these ruminations, I looked up the work in the booklet: Plumed Serpent by Paul Thek.

Hmm. In the Christian tradition serpents are often associated with the devil. However, in Numbers 21:1–9, Moses lifts one up on his staff in the wilderness and it becomes an agent of healing and even a symbol of Christ himself, lifted up on the cross for the salvation of the world (John 3:14–15).

The description in the booklet informed me that “plumed serpent” is the English translation of the Nahuatl name Quetzalcoatl, an Aztec creator-god. I don’t know much about pre-Columbian mythologies, so I looked him up when I got home. Apparently he represents the union of earth (reptile) and sky (feathers), and he is also known as the god of the morning star. (Jesus also calls himself the bright morning star!) Although he was initially portrayed as a large snake covered in quetzal feathers, from 1200 onward, he often appeared in human form, wearing shell jewelry and a conical hat. What I find most striking about his story is that he gave new life to humankind by gathering their bones from the land of the dead, grinding them down, and mixing them with his own blood from self-inflicted wounds.

I also did some research on the artist, of whose work Kolumba has the most comprehensive holdings. Paul Thek was a devout Catholic, an identity complicated by the fact that he was also gay. He rose to fame in the 1960s with his “Technological Reliquaries,” hyperrealistic wax sculptures depicting severed body parts and chunks of flesh in vitrines, inspired by his visit to the Capuchin catacombs in Palermo. Much of his art deals with death and rebirth, divinity and decay, mystical transformation.

Feathers feature in another piece of his from the same year as Plumed Serpent: Feathered Cross. (See it against the wall in a photo from the 2021 exhibition Paul Thek: Interior/Landscape at the Watermill Center in Water Mill, New York.) The feathers’ softness, their weightlessness, seem to contradict the reality of crucifixion. But I think it’s Thek’s way of conveying the transcendent meaning of that act of self-giving. I also think of how down feathers fill pillows on which we rest. “Come to me, all you who are weary,” Christ says (Matt. 11:28); we can rest on his finished work.

But back to Plumed Serpent. Chalk is its material—its ephemerality must be a nightmare for conservators, and indeed it seems like some of the drawing has partially rubbed away. But this choice of material plays into the artist’s interest in the enduring versus the perishable, and the transitory dimensions of death.

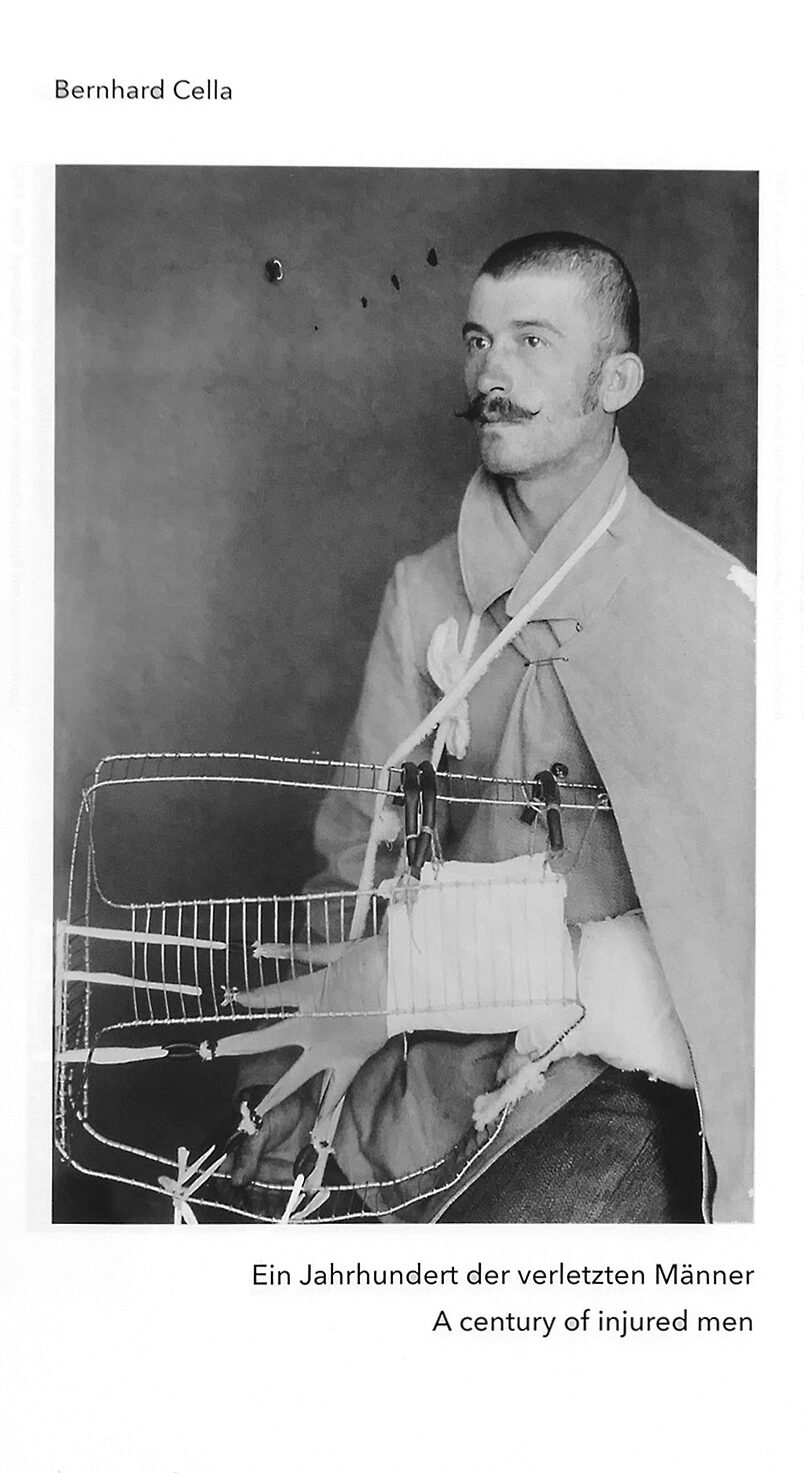

On the right side of room 21, against the wall, are three identical offset-printed artist’s books by Bernhard Cella titled Ein Jahrhundert der verletzten Männer (A Century of Injured Men). Published in 2022, the 152-page book contains photographs of convalescent men over the course of the twentieth century, questioning heroic images of masculinity. I’m assuming many of the injuries were caused by the two world wars.

I neglected to get a photo of the book, but here’s the cover image, and you can view sample pages here and here, as well as two photos of the books in situ at Kolumba on Cella’s Instagram page:

Vulnerability, injury, sacrifice, healing, the transmutation of pain, new life—these are the themes I gathered from this room.

The current Kolumba exhibition features much more contemporary art than medieval—there are some 175 contemporary works on display, compared to six from the Middle Ages—and I suspect that is now their modus operandi. So, the cross-temporal dialogue isn’t happening in every room, at least not explicitly.

I appreciate the uniqueness of this ecclesiastically run museum, acquiring and showing contemporary works by artists from a range of backgrounds while not shunning its own history as collectors and preservers of medieval German religious art.

As a Christian, I found myself latching on to the imagery that was familiar to me, like Jesus as the Man of Sorrows, and interpreting the surrounding works in light of that. But it seems to me the interpretive process could also move in the other direction, and I wonder how a visitor who doesn’t share my Christian vantage point would respond to the two rooms I’ve highlighted.

For two additional artworks I photographed at Kolumba, an ivory crucifix and an installation with coat, hat, and oil lamp, see my Instagram shares here and here.

Part 2, my reflections on my KMSKA visit, will be published tomorrow.