Juneteenth (June 19) is a federal holiday in the United States celebrating the liberation of enslaved African Americans in Texas in 1865. Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, but it was not implemented in places still under Confederate control, and because Texas, being on the westernmost edge of the Confederacy, was farthest from the military action of the Civil War, Texans could conveniently continue to enslave, as there were no soldiers there to enforce the executive decree. But when Union troops, both white and Black, arrived in Galveston Bay on June 19, 1865, two months after the official end of the war, they saw to it by threat of force that the 250,000-plus enslaved Black people in the state were freed.

Also known as Emancipation Day or Jubilee Day (after the year of release mandated by ancient Israelite law), Juneteenth has been celebrated by African American communities in Texas ever since the first anniversary of the freeing event. Historically, the church has been at the center of these celebrations, as the formerly enslaved attributed their liberation to God, to whom they gave effusive thanks and praise. In the twentieth century, Juneteenth expanded into other states but still remained very niche, until 2021, when, after decades of lobbying by Black activists, President Joe Biden signed into law the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act, moving the holiday into the mainstream.

Juneteenth marks not only that one historic day but also, more broadly, freedom as an ongoing struggle. It’s not as if the illegalizing of chattel slavery, or even the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, ended racial oppression or prejudices, which manifest today in, for example, the racial wealth gap, voter suppression, and disparities in policing. We have made important progress as a country, for sure, but there’s still a ways to go until everyone breathes free.

Bishop T. D. Jakes of The Potter’s House in Dallas says that Juneteenth must involve a reckoning with our nation’s sordid past and a commitment to identifying and rooting out whatever sordidness persists. “It’s vital we all must remember when liberty and justice is delayed or denied, it causes traumatic ripples throughout future generations. . . . As we collectively stop to acknowledge and learn from the delayed liberties of our nation’s ancestors, we must not allow those same systems to repeat injustices.”

In recognition of Juneteenth, I’ve compiled on Spotify 118 songs of Black joy, liberation, and faith. From Beyoncé to Duke Ellington, Adolphus Hailstork to Rhiannon Giddens, Mary Lou Williams to Richard Smallwood, these artists jubilate, extol, lament, protest, revel, testify, and hope.

I acknowledge the complications of me, a white person, offering this playlist. I have grappled with how to appropriately celebrate Juneteenth and how to balance its predominant tone of joy (am I allowed to feel joy?) with an honest accounting of past and present evils that mark the Black experience in America, especially slavery and its legacy. One basic piece of advice I’ve heard is to center Black voices. Listen to and lift up Black historians, Black theologians, Black novelists, Black songwriters, etc.

The Art & Theology Juneteenth Playlist combines sacred and so-called secular music written and/or performed by Black artists and exhibiting a spirit of defiant joy. It emphasizes the beauty, power, creativity, and divine belovedness of Black people.

Honoring the religious roots of Juneteenth and the faithful ongoing witness of the Black church, I have incorporated many Christian songs, especially those that speak to the imago Dei and to God’s faithfulness, guidance, and deliverance. The Bible is full of divine deliverance tales: the Israelites from slavery in Egypt; Daniel from the lions’ den; the three Hebrew boys from the fiery furnace; Jonah from the belly of the whale; Paul and Silas from prison. “Didn’t my Lord deliver Daniel? Then why not every man?” sings one spiritual. Another, “Go Down, Moses,” confronts Pharaoh, a stand-in for white Southern enslavers, with the demand “Let my people go,” while yet another exults in the toppling of Pharaoh’s power—“Pharaoh’s army got drownded.” The spiritual “Satan, We’re Gonna Tear Your Kingdom Down” addresses the Enemy directly, expressing resolve to overthrow demonic systems and ideologies, such as white supremacy.

There are also plenty of feel-good vibes on the playlist, lighter songs like Lee Dorsey’s “Occapella,” Count Basie’s “Jumpin’ at the Woodside,” and Jon Batiste’s “Freedom” (with its stylish, smile-inducing music video that I can’t get enough of!):

There’s also the gospel song “This Joy” by Shirley Caesar, sung by the Resistance Revival Chorus:

Its first verse is: “This joy that I have—the world didn’t give it to me. . . . The world didn’t give it, and the world can’t take it away.” “This strength,” “this love,” and “this peace” follow in subsequent verses—otherworldly qualities given to us by God, as Caesar makes explicit in the original, and which no one can ever steal from us. No matter what harm people may do to us, we still possess these inner gifts, which help us face whatever comes.

Composed in the antebellum South, “No More Slavery Chains for Me” (aka “Many Thousands Gone” or “No More Auction Block”) holds together proclamation and grief. The speaker boldly asserts her freedom: “No more slavery chains,” “no more auction block,” “no more peck of corn,” “no more driver’s lash,” “no more mistress’ call,” “no more children stole from me.” It could be spoken by someone who is still enslaved but who refuses to tolerate that condition any longer, or it could be spoken by someone recently freed, rejoicing in what she has escaped. But the solemn refrain, “Many thousands gone,” remembers the multitudes whom slavery has killed. Here’s a performance by mezzo-soprano Shirley Verrett, an international opera star active from the late 1950s through 1990s:

Often words fail to capture the emotional intensity one might feel. “Triptych: Prayer / Protest / Peace” by Max Roach, from his 1960 avant-garde jazz album We Insist!: Freedom Now Suite, featuring Abbey Lincoln, consists almost entirely of wordless vocal expressions, screaming, and sighing, along with drumming by Roach. It’s mournful and alarming. The only words are at the beginning of part 3: “I need peace.” Cued up here (starting at 5:50) is Lincoln and Roach’s performance of the first two parts of “Triptych” for a Belgian TV station that aired January 10, 1964. (The earlier song in the video is “Tears for Johannesburg,” from the same suite.)

In the liner notes for We Insist!, Nat Hentoff writes that “Triptych” is a “final, uncontrollable unleashing of rage and anger that have been compressed in fear for so long that the only catharsis can be the extremely painful tearing out of all the accumulating fury.”

From the same era and genre is “They Say I Look Like God” from The Real Ambassadors, a jazz musical by Dave Brubeck and Iola Brubeck that never made it to the stage but that was recorded in the studio in 1961 and released a year later. Sung by Louis Armstrong, the song opens with these humorous lines, which Armstrong delivers with chilling earnestness:

They say I look like God

Could God be black? My God

If all are made in the image of Thee

Could Thou perchance a zebra be?

This is one-half of the first of four verses, all of which are interspersed with lines of scripture from Genesis 1 and 1 John 4 intoned, like a liturgical chant, by the trio Lambert, Hendricks & Ross, affirming the inherent goodness of Black folks, bearers of the divine breath. Verses 2 and 3 are addressed to God, pleading that he would show “that our creation was meant to be.” The final verse expresses longing for the day

When God tells man he’s really free

Really free

Really free

Really free

The creation narrative of Genesis 1 is also where Sho Baraka’s “Black as Heaven” opens—with beautiful Blackness, sacred humanity. Historically the color white has been used to symbolize goodness, purity, and heaven, but Baraka turns that symbol inside out and declares that he is “black as heaven.” If God created all humans in his image and many of those humans have black skin, then Blackness is a reflection of God. The Creator loves what he created, and we should too.

Heaven is full of Black saints and will continue to fill with such. The song lists many from across the fields of politics, music, history, education, theology and homiletics, agricultural science, and the culinary arts: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., King Ezana of Aksum, King Lalibela of the Zagwe dynasty, Mahalia Jackson, Athanasius, Mary McLeod Bethune, George Washington Carver, David Walker, Edna Lewis, Carter G. Woodson, Bishop G. E. Patterson, Sister Rosetta Tharpe. These men and women are all “black as gold,” not in the sense that they are commodities or currencies, but rather are holy, luminous; and black as life-giving soil.

This is one of the songs commissioned for the 2022 documentary Juneteenth: Faith and Freedom [previously], and it includes a rap by Mag44 of Zambia. There’s so much richness in it, and I encourage you to follow along and sit with the lyrics, investigating any unfamiliar references and, depending on your background, humbly receiving the critiques or gladly receiving the affirmations.

In addition to hip-hop and jazz, the playlist is full of songs from the civil rights movement, such as “Woke Up This Morning with My Mind.” This old gospel song was recorded by Roosevelt and Uaroy Graves in 1936 and adapted in 1961 by the Rev. Robert Wesby, a Baptist minister from Aurora, Illinois. Wesby first sang it while spending time in jail in Hinds County, Mississippi, as a Freedom Rider, replacing the repeated word “Jesus” with one of Jesus’s key platform goals, “freedom”: “Woke up this morning with my mind stayed on freedom.”

This song became an important one in civil rights marches, and is led in the above recording by the famous activist Fannie Lou Hamer. For subsequent verses, she sings “Walkin’ and talkin’ with my mind . . . ,” “Singin’ and prayin’ with my mind . . . ,” “Ain’t no harm to keep your mind . . .” Stayed on freedom.

“Ain’t No Grave” is another traditional gospel song, first recorded by Bozie Sturdivant in 1942 and then by Sister Rosetta Tharpe in 1946–47. It’s about the general resurrection, when the saints will be called up out of their graves, but it’s also about indestructibility, the refusal to be or stay buried. I chose a more recent arrangement performed by jazz vocalist Tiffany Austin [previously], from her 2018 album Unbroken:

Hers starts off with the percussive sounds of a ring shout, a style borrowed from the Gullah Geeche of South Carolina’s Sea Bird Islands, and then goes on to incorporate scat singing. It’s full of enthusiastic energy!

One of the most powerful songs on the playlist is “Make It Home” by Tobe Nwigwe, written after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020. The song is “for the nappy heads in heaven, with a nappy-head Christ by they side”—for Blacks who have died.

It’s also a prayer and a blessing for Blacks who are living. “I pray you catch a wave that doesn’t subside. . . . May your streets be paved with gold. Hope my whole hood make it home.” He prays that his friends, family, and neighbors are able to make it safely back to their homes each night and are not killed in the streets. But “home” operates on other levels as well. To be at home with yourself, for example, is to feel whole, confident, secure in your body. Home also implies belonging. And of course “home” can also mean heaven, that place of ultimate freedom and rest. Are we creating the necessary conditions for freedom and rest here on earth as it is in heaven?

I learned about this song from Dr. Mary McCampbell (see the February 17, 2022, installment of her newsletter, The Empathetic Imagination), who teaches the music video in her humanities class at a Christian university.

Collectively, the songs on this playlist reflect the multifaceted spirit of Juneteenth, which encapsulates exultation, passion, power, praise, irrepressibility, resistance, sorrow, anger, and hope and trust. Like Juneteenth itself, the playlist is a looking back and a looking forward. We Americans are a people “on our way.” The work of emancipation is unfinished. These Black artists invite us to join the work.

I invite you, as a way of commemorating the holiday, to:

1. Choose one of the songs and pray from it.

2. Choose one of the artists and explore more of their oeuvre.

3. Choose one of the older songs and explore its origin and history, learning more about the context from which it arose and how it has been received over the decades. Listen to other renditions to see the different ways it’s been interpreted.

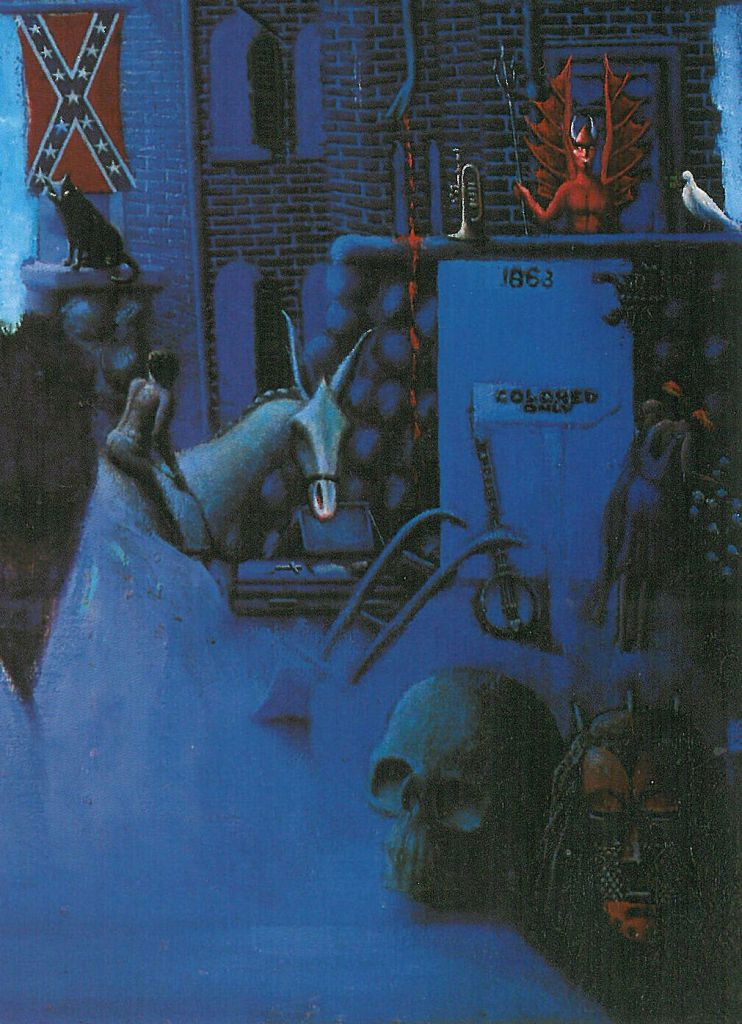

The image on the playlist cover is cropped from a photo I took a few years ago at Duke University Chapel of the linocut Ain’t No Grave by Steve A. Prince (2019), which shows a dancing winged figure emerging from the head of Carlotta Walls LaNier, the youngest of the Little Rock Nine, as she integrates the city’s high school in 1957. It is an embodiment of LaNier’s mighty spirit, and that of other Black “agents of God,” to use Prince’s term, who pursue freedom for themselves and others.