LOOK: Adoration of the Magi by Silvestro dei Gherarducci

(See commentary below.)

LISTEN: “Ecce advenit dominator Dominus” (Behold, the Sovereign Lord Is Come), introit for the Epiphany of the Lord, ca. 7th century | Performed by Floriani (men’s vocal ensemble), 2024

Ecce advenit dominator Dominus:

et regnum in manu eius

et potestas et imperium.

Deus, judicium tuum regi da,

et justitiam tuum filio regis.

Gloria patri,

et filio, et spiritui sancto,

sicut erat in principio,

et nunc, et semper,

in saecula saeculorum. Amen.

Behold, the Sovereign Lord is come,

and in his hand the kingdom,

and power, and dominion.

Give the king your justice, O God,

and your righteousness to a king’s son.

Glory be to the Father,

and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit,

as it was in the beginning,

is now, and ever shall be,

world without end. Amen.

In the Roman Catholic Church, the introit (sung while the priest approaches the altar for the Eucharist) for the Mass of the Epiphany is derived from three Old Testament texts: Malachi 3:1, 1 Chronicles 29:12, and Psalm 72:1. It communicates the royalty of Christ.

The church has sung this cento since as far back as the seventh century. The musical notation has been preserved in graduals (books that collect all the musical items of the Mass).

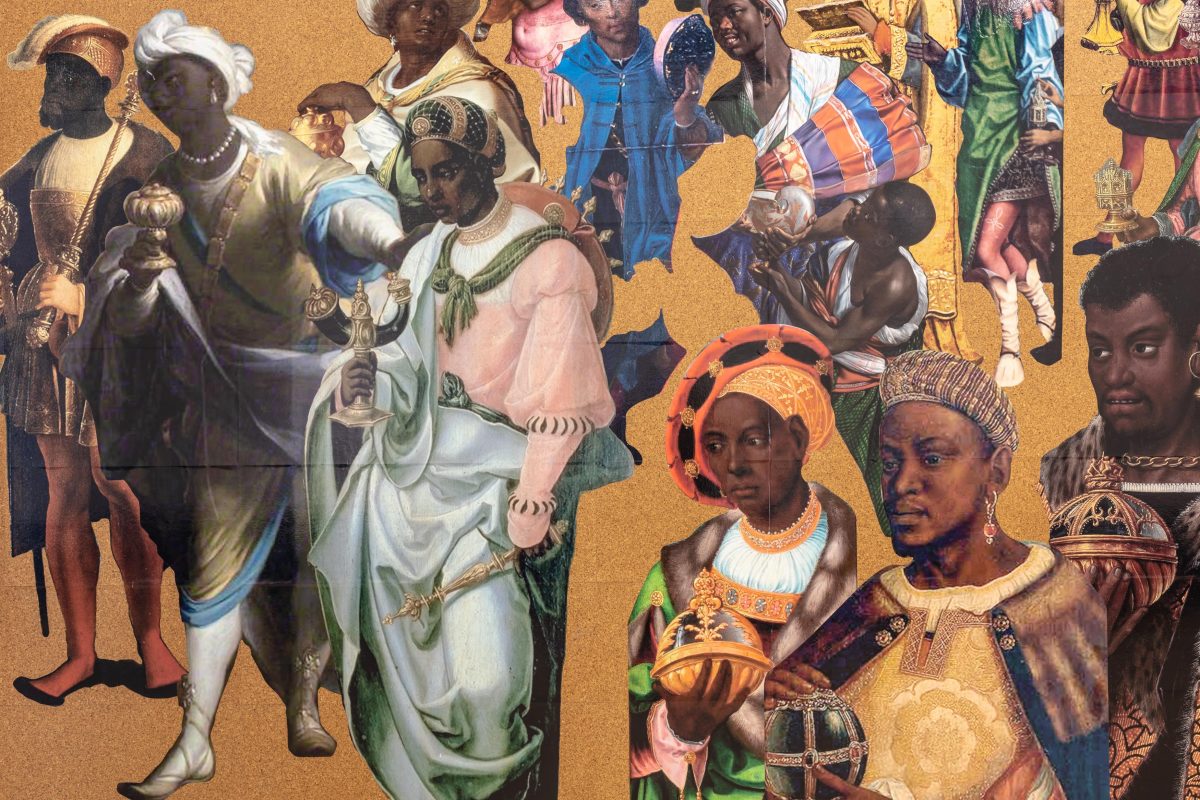

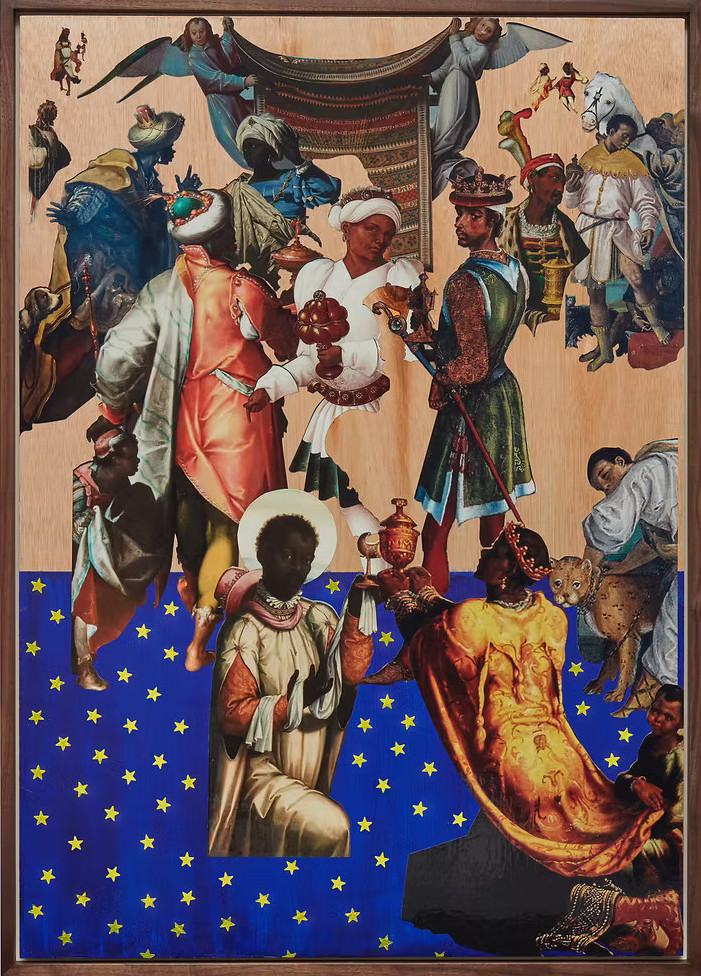

Two years ago at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, I saw an Ecce advenit leaf from a now-dispersed medieval gradual that caught my attention with its glimmering gold. It’s one of twenty-three cuttings that the museum owns from a manuscript made at the Camaldolese monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Florence, Italy, in the late fourteenth century, for the monastery of San Michele a Murano in Venice. The illuminations are by the then-prior (head) of Santa Maria, Silvestro dei Gherarducci.

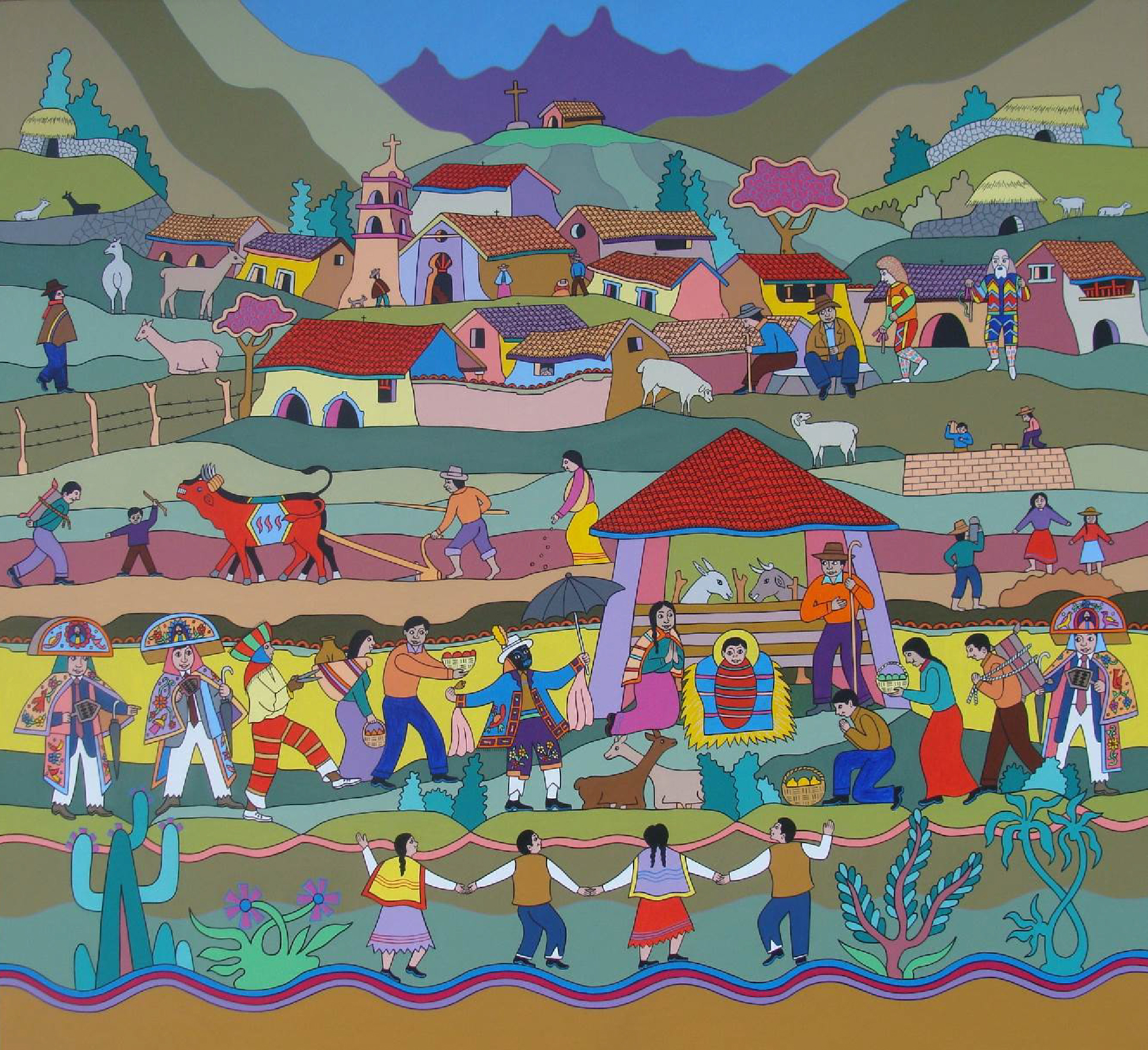

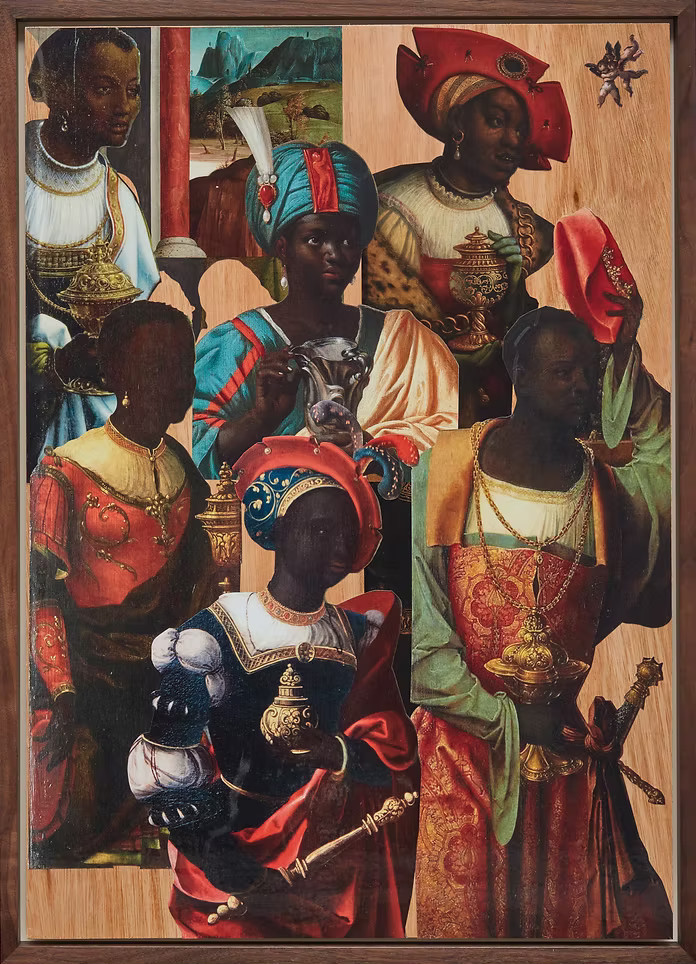

The primary image on the page is an Adoration of the Magi inside a letter E (for Ecce). When a scene or figures appear inside a large decorative letter at the start of a text section, it’s called a historiated initial.

In the scene, the Holy Family stands at the mouth of a cave—Jesus is seated on Mary’s lap, while Joseph stands beside them holding a vessel that the elder magus handed him, a gift for the Christ child. It was typical for artists to depict the three magi as different ages: young (beardless), middle-aged, and elderly (gray-haired). The oldest of the group kneels on the ground, lays down his crown, and kisses Christ’s feet while the other two await their turn. In the background, a servant restrains two bridled camels.

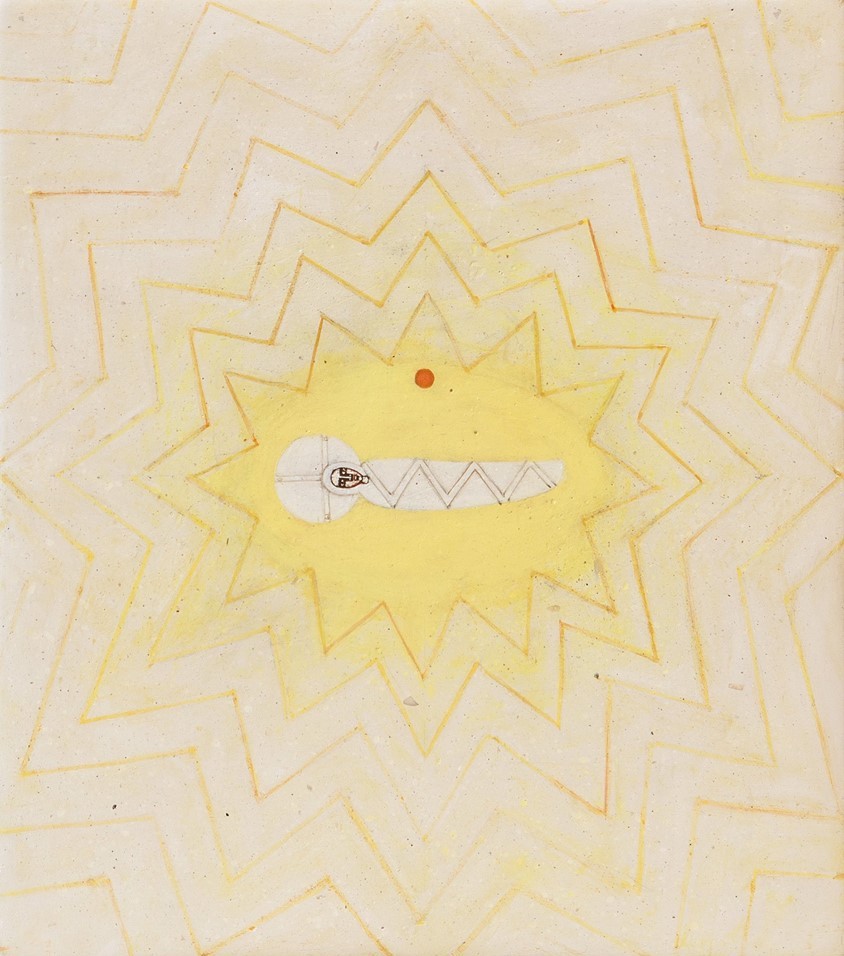

Across the top and left margins of the page is a colorful vine scroll, and in the lower margin there’s a bas-de-page depicting the magi following the star. I love their fantastic hats! The elder one, astride a horse, points the way forward (the guiding star shines from the left of the page near some blue foliage); the other two follow his direction on camels. In front of the caravan are two servants, one walking on foot with a bag slung over his shoulder, and the other riding a camel beside a second camel carrying a chest that contains the treasures the magi will bestow on the newborn king they’re journeying to pay homage to.

I like to imagine the community of Camaldolese monks in late medieval Venice singing from this choirbook on Epiphany, the lovingly wrought images of Christ-pursuing, Christ-worshipping magi enlivening their engagement with the gospel story and supplementing their own worship.

While monastic choirs have retained the monophonic style of music (that is, a single melody line sung in unison or traded off) that the church used for most of the Middle Ages—what we call Gregorian chant—over time, the church at large developed a taste for more elaborate, polyphonic music (that is, music with two or more simultaneous but relatively independent melodic lines), which came into full flower during the Renaissance and was sung in cathedrals.

To illustrate the difference between medieval monophony and Renaissance polyphony, here’s an example of the latter: the English composer William Byrd’s setting, from 1607, of the Ecce advenit. During his lifetime it was sung in Epiphany services in the Church of England as well as in the manor houses of recusant Catholic families (who were forced by law at the time to worship clandestinely).

Epiphany is no isolated and solitary act. It is a process: it is eternally typical of the Divine character. We will not merely look back over the long centuries at the manifestation that first flashed forth before the eyes of the Three Wise Men. Here and now, God is revealing Himself afresh before our very eyes. . . . For us too, clogged and choked by the dismal sand, there is a star that guides, a God who beckons. If only we would see!

—Henry Scott Holland (1847–1918) [HT]

May you see God’s light and, with curiosity and intent, follow it. Find what it illuminates.

A blessed Epiphanytide to you all.