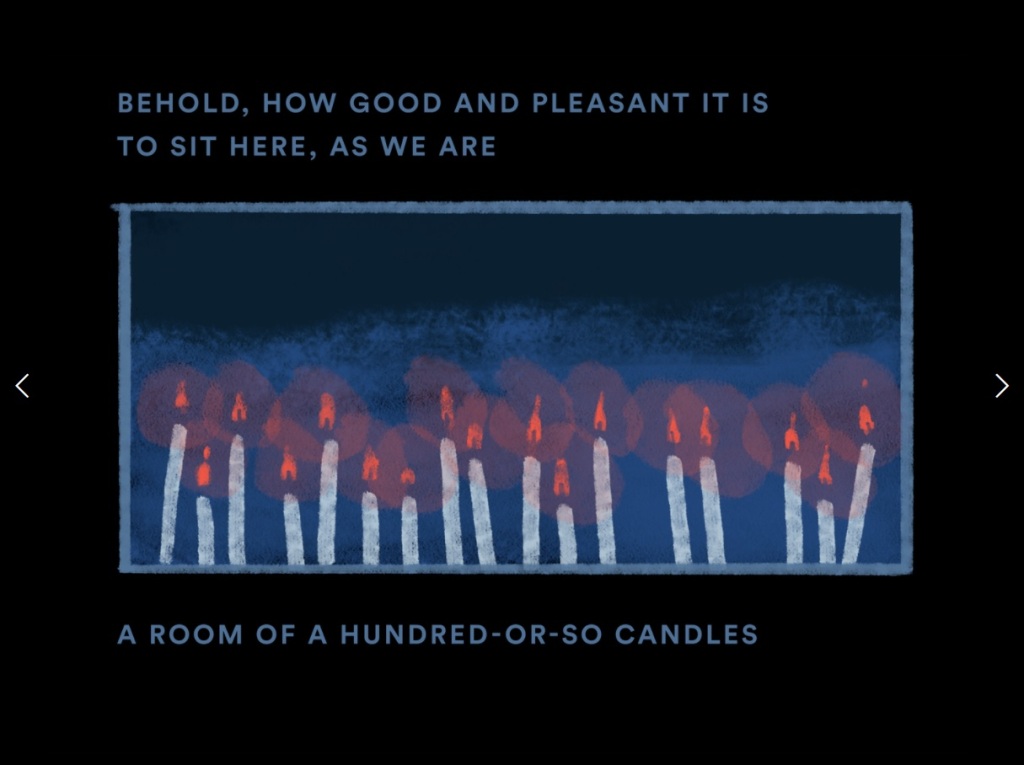

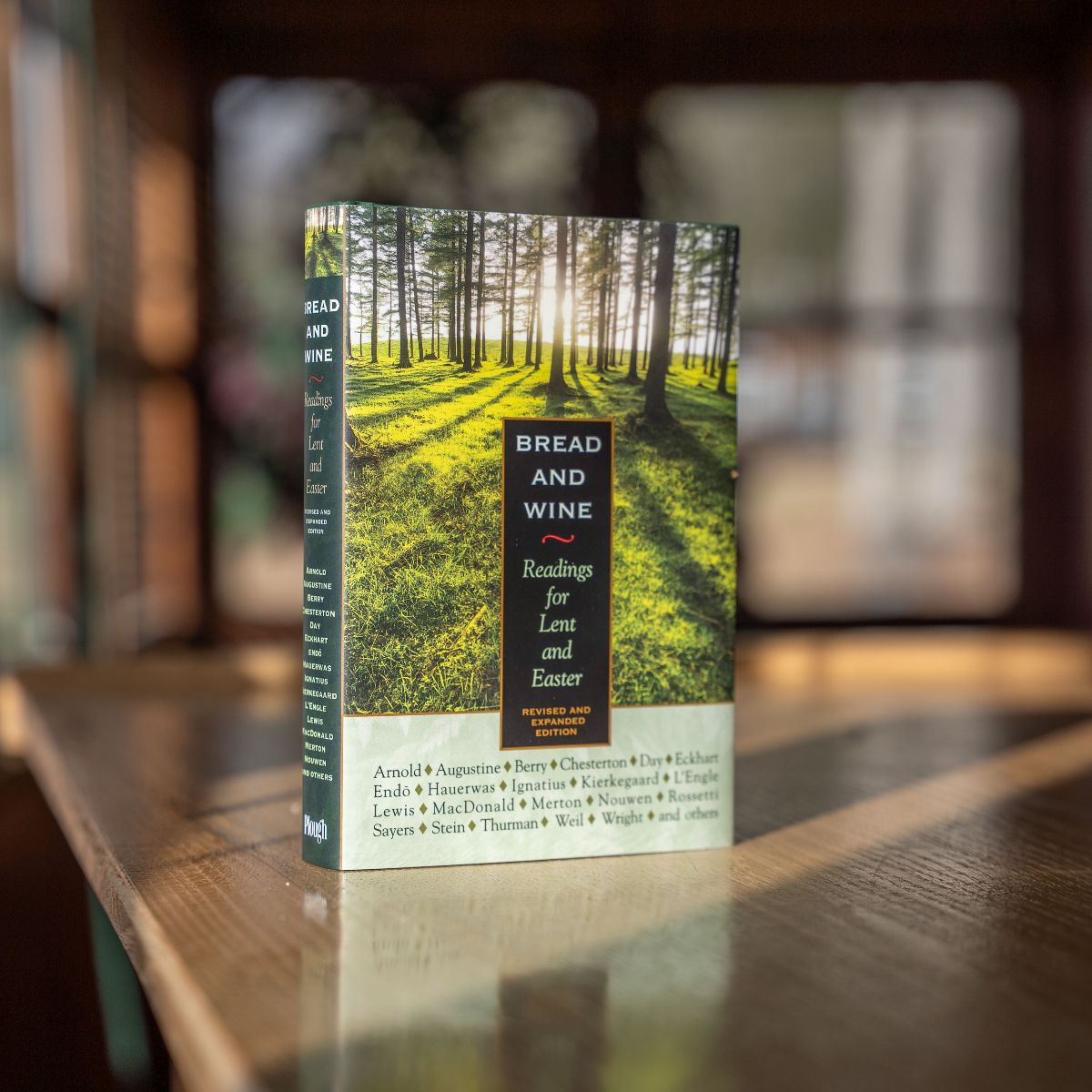

NEW BOOK: Bread and Wine: Readings for Lent and Easter, Second Edition: Plough is the publishing house of the Bruderhof, an international Anabaptist communal movement. This year they released a revised and expanded edition of their popular Lent and Easter devotional, increasing the original seventy-two entries to ninety-six to cover the full fifty days of Easter—although the last section is themed around Pentecost. The selections are all from previously published material, but what a treasure-house has been curated here from across denominations, countries, and eras, from early church fathers to medieval mystics to modern saints. Clement of Rome, Julian of Norwich, Kahlil Gibran, Watchman Nee, Gonzalo Báez Camargo, Thomas Merton, Simone Veil, Howard Thurman, Toyohiko Kagawa, Barbara Brown Taylor, Jürgen Moltmann, Tish Harrison Warren—these are some of the many voices included here that reflect on and expound the beautiful truths of the Lent and Easter seasons. Each reading is just a few pages long, so it’s easy to pick up with your morning coffee or just before bed.

Besides the expansion, other changes I’ve noticed in this edition are:

- Thinner pages, which, despite the additional content, reduce the overall thickness of the book

- The epigraph at the beginning of each reading was removed, as these were not the authors’.

- Thirteen of the original readings were replaced, possibly due to permissions costs, but maybe also just to get in some fresh voices or content, and in one case, to remove an accused sex abuser.

- A misattribution in the original to Mother Teresa was corrected to Joseph Langford, who founded the Missionaries of Charity Fathers with her.

- There is a slight reordering of readings so that pertinent meditations appear during Holy Week.

I’ve provided a link to the Plough book page above, but you can also purchase through Amazon or your retailer of choice.

+++

SONGS:

I grew up in an independent Baptist church, ignorant of most of the historic prayers of the church at large. The first time I ever heard the phrase “Kyrie eleison” [previously] was on track 5 of the Christian recording artist Mark Schultz’s 2001 album Song Cinema, which is a cover of an eighties rock song by Mr. Mister. I was in middle school, and I had to look up what it meant. Derived from a prayer found in multiple places in the Psalms and the Gospels, “Kyrie eleison” (pronounced KEER-ee-ay eh-LAY-ee-sohn) is Greek for “Lord, have mercy,” and it’s traditionally followed by “Christe eleison”—Christ, have mercy. An inheritance from early Eastern Christian liturgies, it has been part of the Ordinary of the Catholic Mass since the fifth century, which means it’s recited or sung in every eucharistic service regardless of the liturgical season, and it’s used in many other Christian traditions as well. I’ve never been part of a church that sings the Kyrie, but I occasionally sing it in my personal devotions. It’s been set to music by hundreds of composers, for choirs, contemporary bands, and more. Here are two settings that I’ve recently come across and enjoy, followed by a song that entreats (God’s?) mercy on father, brother, church, country, and every living thing.

>> “Kyrie (Lord, Have Mercy)” by Robert Alan Rife: This song was written by Robert Alan Rife [previously], a minister with the Evangelical Covenant Church, serving in Edinburgh. It’s performed here by worship musicians at Great Road Church (formerly Highrock Covenant Church) in Acton, Massachusetts. The lead vocalist is Caelyn Jarrett Poetz; she’s accompanied on guitar by her dad, Travis Jarrett, the church’s music pastor, and Hannah Moulton provides backing vocals. Rife tells me you can purchase the sheet music here, and that other songs of his can be streamed on Spotify, Apple Music, etc.; he has not yet recorded this one, but it’s in the works.

>> “Kyrie” by Paul Smith: This peaceful, resonant setting of the Kyrie was composed by Paul Smith, cofounder of the Grammy-nominated British vocal ensemble VOCES8, who perform it here. The song appears on Smith’s 2025 album Revelations.

>> “Mercy Now” by Mary Gauthier: In this video from the 2010 Americana Music Festival in Nashville, folk singer-songwriter Mary Gauthier (last name pronounced go-SHAY) performs her most famous song, “Mercy Now,” originally released on her 2005 album of the same title. It doesn’t directly invoke God, but it feels like a prayer, asking for mercy (forgiveness, relief, compassion, lovingkindness) first for two family members—her father on his deathbed, and her drug-addicted brother—and then for the institutions of church and state, both in need of repair, and then for everyone: “We all could use a little mercy now / I know we don’t deserve it / But we need it anyhow,” and “only the hand of grace” can give it, can intervene to save us from our self-destructive ways. In response to the song’s being listed as “one of the saddest 40 country songs of all time” by Rolling Stone in 2014, Gauthier said, “It is not a sad song. It is about hope.”

+++

EXHIBITION: Sanctuary by Nicholas Mynheer, February 18–April 12, 2026, Portsmouth Cathedral, UK: One of my favorite artists, Nicholas Mynheer, has a show that opened on Ash Wednesday at Portsmouth Cathedral, aka the Cathedral of the Sea, and that will continue for the duration of Lent plus some. “The exhibition features paintings and sculptures that explore the experiences of refugees, both ancient and contemporary. The story of Jesus, Mary and Joseph fleeing to Egypt sits alongside the realities faced by people crossing the English Channel today. Mynheer’s work doesn’t offer easy answers – instead, it asks questions. What would we do if our home were no longer safe? How do we respond to those seeking refuge? What does it mean to hope for a better life when the risks are so great?”

View artworks from the exhibition on the artist’s website at https://www.mynheer-art.co.uk/gallery/sanctuary-exhibition.html. Follow him on Instagram @mynheer_art. Mynheer writes:

As an artist, one of the themes that I’ve been drawn to repeatedly is that of the Holy Family on the Flight to Egypt. The fact that even Jesus, Mary and Joseph became refugees to escape the wrath of Herod reminds us that it could happen to any one of us.

Over the past years we have become increasingly aware of the plight of refugees; from Syria, Afghanistan, Ukraine, Somalia, along with daily reports of refugees attempting to cross the English Channel. Whether they flee from war, persecution, famine, political instability or for economic reasons, the risks are the same; all driven by hope, the hope of a better life.I often wonder what I would do if I lived in a country ravaged by war? What would I do if I was persecuted for my faith, my colour or my culture? What would I do if scrolling on my phone, others’ lives seemed easier, happier, and all I had to do was get there?

It is my hope that these meditations in paint and stone might draw us in to question how we might respond if we, like Jesus, Mary and Joseph, were forced to seek refuge; to be refugees . . . to search for Sanctuary.

Starting February 25, Portsmouth Cathedral is offering a free four-week Lent course (classes are in person on Wednesday evenings) inspired by the exhibition. The first class will be a talk by Mynheer himself, and the other three will be led by clergy, exploring biblical themes of journey, rescue, and redemption through the art on display.

+++

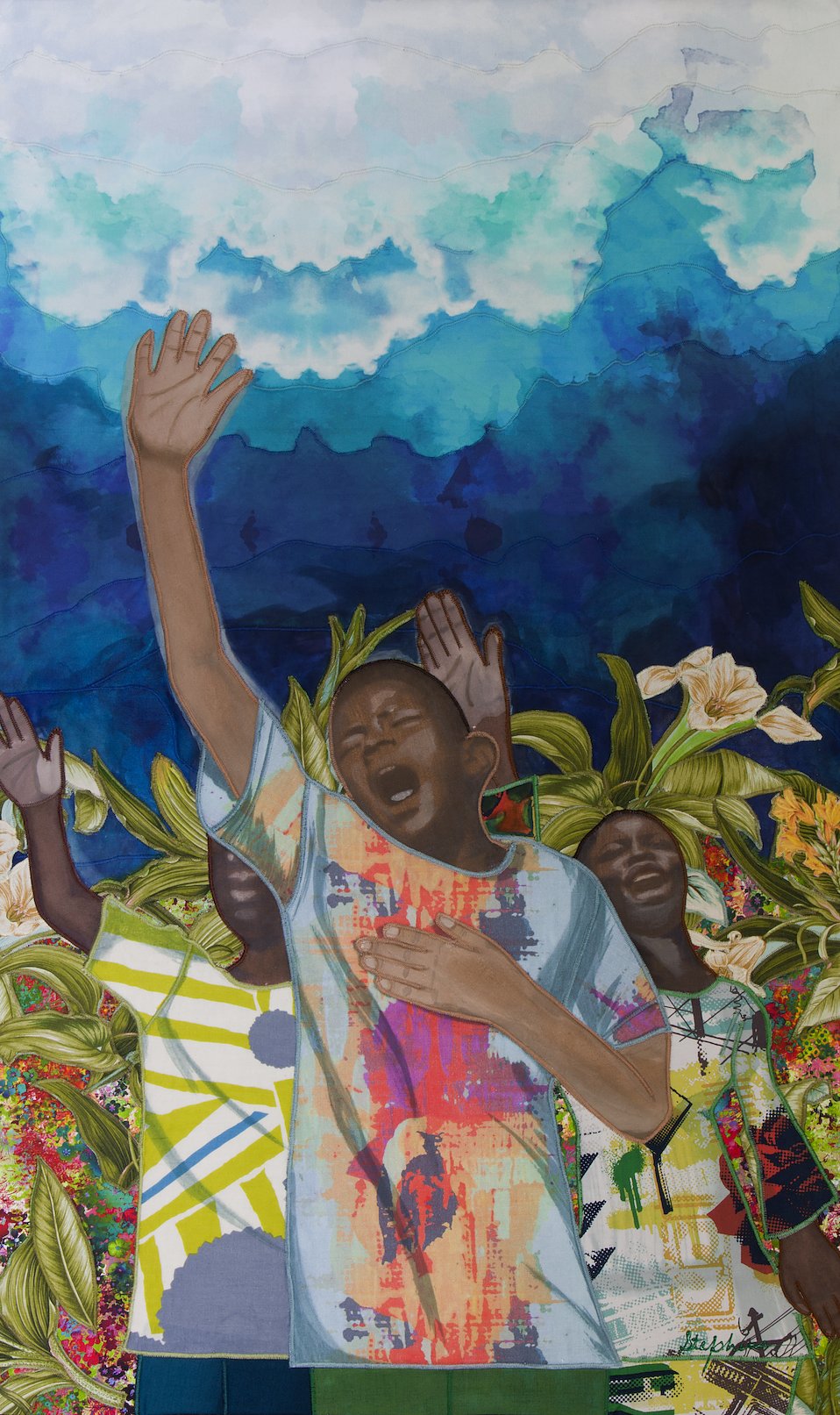

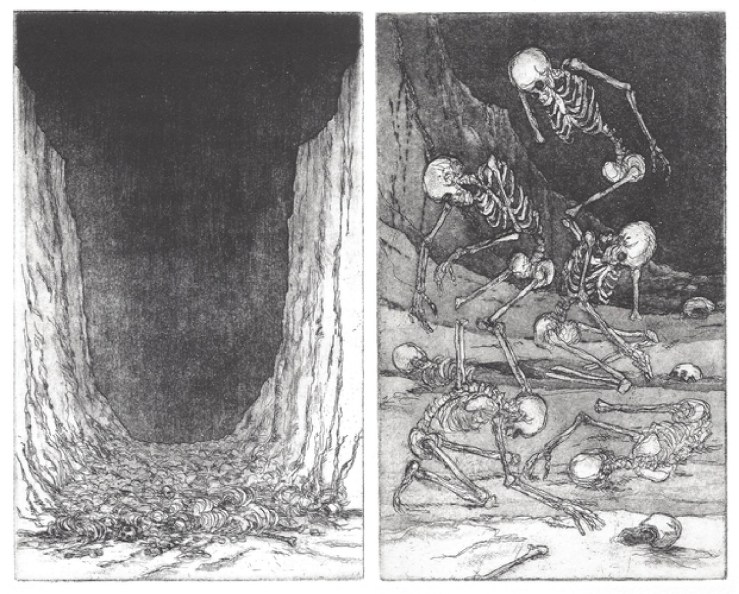

CALL FOR ART: The Valley of Dry Bones, Museum of the Bible, Washington, DC: “The Valley of Dry Bones art invitational seeks to inspire the creation of new artwork based on Ezekiel 37:1–14, the biblical vision in which God brings life, renewal, and restoration to a valley of dry bones. Museum of the Bible invites Christian and Jewish artists residing in the continental United States to create original pieces in a variety of media that show their personal and spiritual reflections on this powerful theme. The goal is to show how the Bible can shape modern art and give visitors a meaningful way to connect with biblical themes through creativity. Museum of the Bible will choose 15 artists through a national call and design a professional exhibition to showcase their art from May 7–November 7, 2027. The museum will also help promote the artists and their work through talks, social media, and special events. Each artist chosen will be paid a stipend of $3,000 to cover the costs of creation, travel, and shipping.” Entry deadline: April 24, 2026.

Here’s a double print on the subject by my friend Margaret Adams Parker, aka Peggy:

+++

SHORT FILM: Forevergreen (2025), dir. Nathan Engelhardt and Jeremy Spears: With the announcement of the 2025 Academy Award nominations last month, I learned that Forevergreen is one of five nominees for Best Animated Short Film! Written and directed by two Christians in the animation industry (employed by Disney but working independently here) and executed by a team of over a hundred, Forevergreen is a thirteen-minute gospel-oriented film in which “an orphaned bear cub finds a home with a fatherly evergreen tree, until his hunger for trash leads him to danger.” I found out about it last November through the music artists who wrote the soundtrack, Josh Garrels and Isaac Wardell, and am delighted to see it recognized in such a huge way. I really dig its unique animation style, which uses whittled wood figures. The movie is currently streaming for free on YouTube (see embed below), but if you want to see it on a big screen, check your local theater listings.