She lay, skin down in the moist dirt,

the canebrake rustling

with the whispers of leaves, and

loud longing of hounds and

the ransack of hunters crackling the near branches.

She muttered, lifting her head a nod toward freedom,

I shall not, I shall not be moved.

She gathered her babies,

their tears slick as oil on black faces,

their young eyes canvassing mornings of madness.

Momma, is Master going to sell you

from us tomorrow?

Yes.

Unless you keep walking more

and talking less.

Yes.

Unless the keeper of our lives

releases me from all commandments.

Yes.

And your lives,

never mine to live,

will be executed upon the killing floor of innocents.

Unless you match my heart and words,

saying with me,

I shall not be moved.

In Virginia tobacco fields,

leaning into the curve

of Steinway

pianos, along Arkansas roads,

in the red hills of Georgia,

into the palms of her chained hands, she

cried against calamity,

You have tried to destroy me

and though I perish daily,

I shall not be moved.

Her universe, often

summarized into one black body

falling finally from the tree to her feet,

made her cry each time into a new voice.

All my past hastens to defeat,

and strangers claim the glory of my love,

Iniquity has bound me to his bed,

yet, I must not be moved.

She heard the names,

swirling ribbons in the wind of history:

nigger, nigger bitch, heifer,

mammy, property, creature, ape, baboon,

whore, hot tail, thing, it.

She said, But my description cannot

fit your tongue, for

I have a certain way of being in this world,

and I shall not, I shall not be moved.

No angel stretched protecting wings

above the heads of her children,

fluttering and urging the winds of reason

into the confusions of their lives.

They sprouted like young weeds,

but she could not shield their growth

from the grinding blades of ignorance, nor

shape them into symbolic topiaries.

She sent them away,

underground, overland, in coaches and

shoeless.

When you learn, teach.

When you get, give.

As for me,

I shall not be moved.

She stood in midocean, seeking dry land.

She searched God’s face.

Assured,

she placed her fire of service

on the altar, and though

clothed in the finery of faith,

when she appeared at the temple door,

no sign welcomed

Black Grandmother. Enter here.

Into the crashing sound,

into wickedness, she cried,

No one, no, nor no one million

ones dare deny me God, I go forth

along, and stand as ten thousand.

The Divine upon my right

impels me to pull forever

at the latch on Freedom’s gate.

The Holy Spirit upon my left leads my

feet without ceasing into the camp of the

righteous and into the tents of the free.

These momma faces, lemon-yellow, plum-purple,

honey-brown, have grimaced and twisted

down a pyramid of years.

She is Sheba and Sojourner,

Harriet and Zora,

Mary Bethune and Angela,

Annie to Zenobia.

She stands

before the abortion clinic,

confounded by the lack of choices.

In the Welfare line,

reduced to the pity of handouts.

Ordained in the pulpit, shielded

by the mysteries.

In the operating room,

husbanding life.

In the choir loft,

holding God in her throat.

On lonely street corners,

hawking her body.

In the classroom, loving the

children to understanding.

Centered on the world’s stage,

she sings to her loves and beloveds,

to her foes and detractors:

However I am perceived and deceived,

however my ignorance and conceits,

lay aside your fears that I will be undone,

for I shall not be moved.

from I Shall Not Be Moved (Random House, 1990), copyright © Caged Bird Legacy, admin. CMG Worldwide

Maya Angelou (1928–2014) was an African American poet, storyteller, civil rights activist, and lecturer, most famous for her autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969). She began her career as a singer, dancer, and actress but started writing in the late 1950s, often combining personal narrative with advocacy for racial and gender equality. In 1960 she worked as the northern coordinator for Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, before moving to Egypt and then Ghana with her son. She returned to the US in 1965 to help Malcolm X build the Organization of Afro-American Unity.

In addition to seven autobiographies and multiple poetry collections, Angelou also wrote children’s books, cookbooks, essays, short stories, stage plays, screenplays, documentaries, and music (including film scores). She was a recipient of three Grammys for her spoken-word albums, an Emmy nomination for her portrayal of Kunta Kinte’s grandmother in the miniseries Roots (1977), the National Medal of Arts (2000), the Presidential Medal of Freedom (2010), the Literarian Award (2013), and many other honors. Recurring themes in her literary works include hardship and loss, love, social justice, Black beauty, the strength of women, and the human spirit.

In her Nancy Hanks Lecture on Arts and Public Policy, given March 20, 1990, for the American Council for the Arts in Washington, DC, Maya Angelou addressed her audience with a question:

I often wonder what would happen if I could come face to face with a grandparent, a great-great-great-grandparent. Suppose you did? Just imagine. What would happen? Not a specter, a real person, 200 years old, who said, “So . . . You’re the reason I took the lash, you’re it, huh? So you’re the reason I took the auction block, and stayed alive . . . you’re it, are you? How is it with you? How are you doing with the gifts I gave you?”

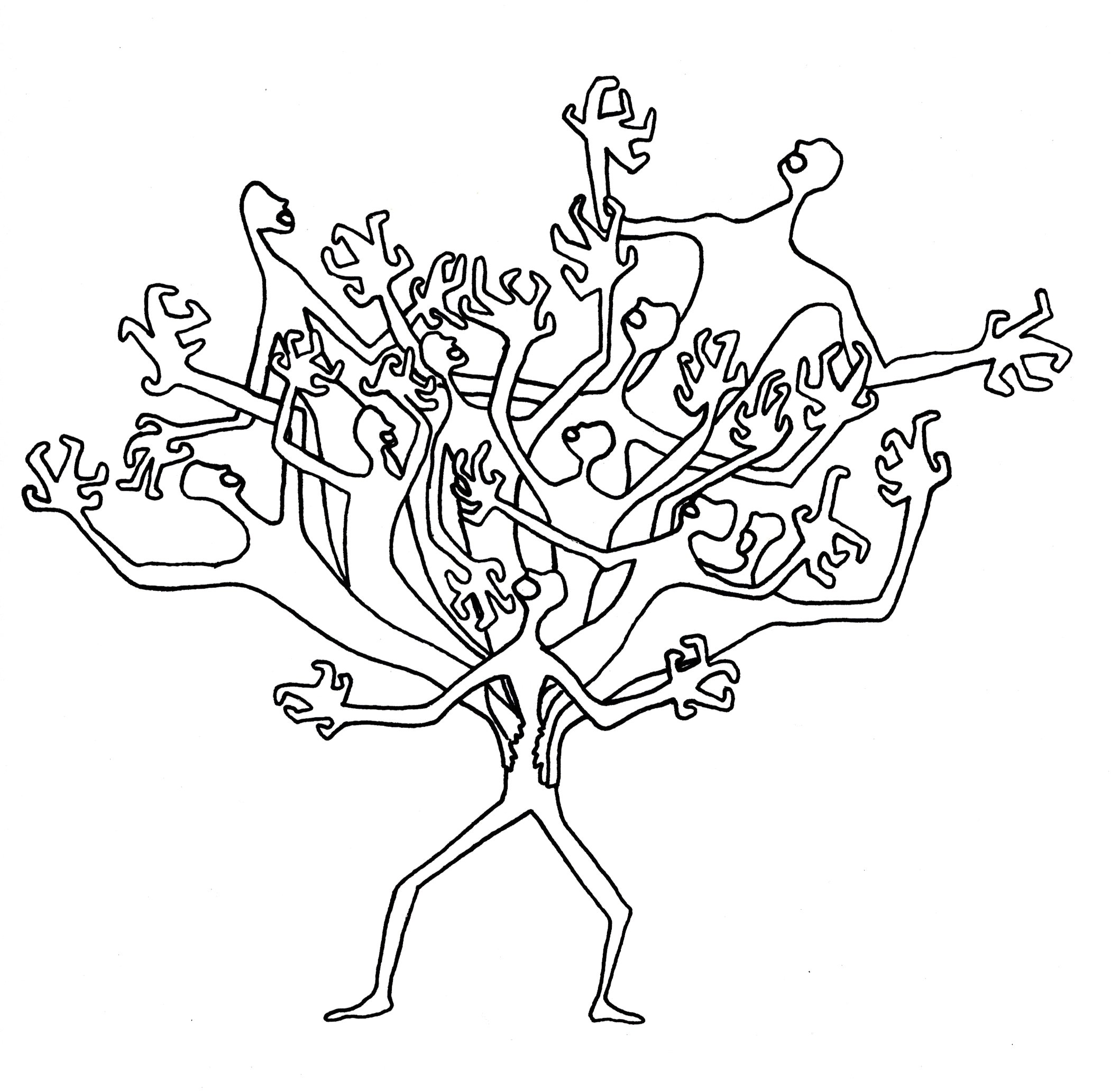

She went on to describe how her grandmother and mother used to sing the African American spiritual “I Shall Not Be Moved” around the house. Its lyrics are based on Jeremiah 17:7–8: “Blessed are those who trust in the LORD, whose trust is the LORD. They shall be like a tree planted by water, sending out its roots by the stream. It shall not fear when heat comes, and its leaves shall stay green; in the year of drought it is not anxious, and it does not cease to bear fruit” (cf. Ps. 1:3; 62:6).

Angelou then talked about the importance of “being flexible so one can bend, resilient so that one can stand erect after being knocked down,” before proceeding to read her poem “Our Grandmothers.”

The poem celebrates the strong Black women who have gone before, that great cloud of witnesses, the ancestors, who stood firm in the face of all kinds of adversity, giving life to succeeding generations. The queen of Sheba (who gifted gold, spices, and jewels to King Solomon of Israel, as 1 Kings 10 relates, and who the ancient historian Josephus said ruled over Ethiopia and Egypt), abolitionist Harriet Tubman, writer Zora Neale Hurston, and educator and philanthropist Mary Bethune are among the women named. Self-assertive, tenacious, filled with holy desire, steadfast in the pursuit of freedom and justice.

Angelou is one of the most banned authors in the United States, particularly in high schools, where some districts deem her books inappropriate for their use of racial epithets and frank depictions of violence, including sexual assault. “Our Grandmothers” is mild by comparison to her first autobiography, but it does allude to lynching and rape and contains a litany of vulgar, demeaning names. She does not want to sugarcoat these realities, this history.

While acknowledging the suffering endured by Angelou’s female forebears, the poem is triumphant in tone. It’s that refusal to despair, that holding on to faith, that Angelou so admires and that impels her to join in that old refrain, composed in chains and having carried her people through countless trials and acts of resistance: “Like a tree planted by the water, I shall not be moved.”