VIDEO INTERVIEW: “InStudio: An Image book launch celebrating Abram Van Engen’s Word Made Fresh, including a conversation with Shane McCrae”: The other week I mentioned the upcoming July 9 virtual event hosted by Image journal with Word Made Fresh author Abram Van Engen, who teaches poetry to university students, church groups, and (through his podcast Poetry for All, which he hosts with Joanne Diaz) an online public. The recording for the Image conversation is now available, in case you missed it!

Van Engen answers questions from poet Shane McCrae and from the audience, addressing how to read a volume of poetry, how poetry produces an experience, the role of understanding and not understanding when it comes to poems, why Christians in particular should read poetry, hymns as poetry, how Adam’s naming creation in Genesis 2 relates to the task of the poet, his favorite poets, and the qualities of a good poem.

Two especially great questions from attendees were:

- How do you imagine poetry nourishing discipleship and/or corporate worship, if used by a church leader?

- What, if anything, would you like to see more of from Christian poets writing today?

Regarding the first, he says,

I often think that ministers in particular—and especially the heavier the preaching tradition, the more true this is—need creative literature—poetry, novels, and other things—to enliven what it is they’re doing from the pulpit. Not just to understand human life in all of its flourishing and misery, but to connect to people in different kinds of ways than pure principle and message can do.

He mentions the recurring summer seminar for pastors co-led by Dr. Cornelius “Neal” Plantinga, “Imaginative Reading for Creative Preaching,” to help participants explore the possibilities and homiletical impact of engaging in an ongoing program of reading novels, poetry, short fiction, children’s lit, and nonfiction outside the category of Christianity—not just to mine for sermon illustrations but also to develop a “middle wisdom” (“insights into life that are more profound than commonplaces, but less so than great proverbs”) and to deepen their perception of people.

+++

PODCAST EPISODE: “Opening Your Bible? Turn on Your Imagination” with Russ Ramsey and Sandra McCracken, The Gospel Coalition Podcast, May 8, 2020: This is a recording of a breakout session—“Reading Scripture with an Engaged Imagination”—from the Gospel Coalition’s 2019 National Conference in Indianapolis. Pastor Russ Ramsey (author of Rembrandt Is in the Wind: Learning to Love Art through the Eyes of Faith) and singer-songwriter Sandra McCracken (“We Will Feast in the House of Zion,” “Thy Mercy, My God”) discuss the role the imagination plays in reading scripture and understanding and conveying its truth.

Scripture calls for reading with a fully engaged imagination, Ramsey says, because that’s how literature works and that’s how people work. “How are you supposed to understand Scripture if you’re not trying to empathize or get into a situation and walk around inside of it?” he asks. They discuss wonder, mystery, and paradox—the unresolved dissonance and complexity present in many Bible stories—and the need to take a Bible story on its own terms instead of always trying to extract a moral or “life application” from it.

Though they don’t use the term, they’re basically advocating for Ignatian contemplation, aka the Ignatian method of Bible reading and prayer, in which you put yourself into the story and try to experience it with all your senses. Ramsey demonstrates with the story of Mary and the nard. “In those hours as Jesus is being arrested and tried and flogged and crucified, he smells opulent. And I think we’re supposed to get that, you know. We’re supposed to . . . especially a first-century reader is going to say, ‘He left a lingering scent as he went down the Via Dolorosa, and it was the scent of royalty. And it was the scent of extravagance.’”

Some of the names that come up along the way are Robert Alter, Ellen Davis, Eugene Peterson, and Frederick Buechner.

+++

IMMERSIVE ART EXPERIENCE: Rembrandt’s Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee at Frameless in London: I’ve been seeing these kinds of exhibitions advertised more and more—ones that use animation and projection-mapping technology and dozens of loudspeakers strategically placed around the room to create a wall-to-wall, multisensory experience built around one or more masterpiece paintings. Some people say it’s gimmicky or overstimulating, but though I’ve never been to one, I generally think they look like fun! They’re not meant to be a substitute for seeing the actual artwork in person.

In the case of Rembrandt van Rijn’s Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, though, that’s not possible, as the painting was stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990 and has not been recovered. In collaboration with their long-term partner Cinesite, Frameless recently developed an immersive art experience based on the painting—the Dutch master’s only seascape—in which visitors can get a sense of the terror and exasperation Jesus’s disciples must have felt that night they were caught at sea in a torrential wind- and rainstorm while Jesus lay calmly asleep in the boat’s stern (see Matt. 8:23–27; Mark 4:36–41; Luke 8:22–25). Here’s a making-of featurette for that experience, which garnered a nomination for a prestigious Visual Effects Society award earlier this year:

Frameless is permanently housed in the Marble Arch Place in London’s West End cultural district. Christ in the Storm is one of forty-two works of art they riff on across four galleries.

+++

POEMS:

Here are two poems published this month that each explores a different episode from the story of Jacob’s family in the book of Genesis—one of his wife Rachel stealing her father’s household gods as they flee to Canaan, and one of Jacob’s sons avenging the rape of their sister, Dinah. Both are examples of how poems can stimulate renewed engagement with scripture, as these were stories I had forgotten some of the details of, and the poems did not make sense until I revisited the relevant Bible passages. Poems can help us walk around inside the biblical narratives, both familiar and unfamiliar ones, and see things from the perspectives of different characters, especially ones who are not given a voice in scripture, such as a Shechemite woman taken captive by Jacob’s sons.

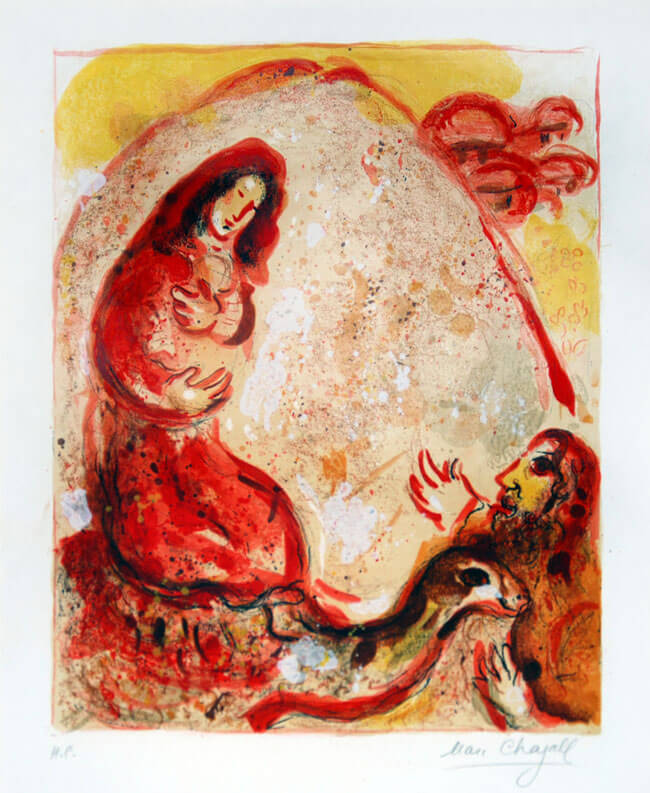

>> “Rachel, Cunning” by Patricia L. Hamilton, Reformed Journal: Read the poem first, then Genesis 29–31, then my commentary.

Voiced by Jacob’s second wife, Rachel, in this poem Rachel vents her jealousy over Jacob having first married her sister, Leah, who bore him six sons to her one at this point. This marriage was due to the trickery of her father, Laban, who also tried to cheat Jacob out of fair shepherding wages—so Rachel resents her father. As she prepares to secretly leave Paddan-aram for Canaan with Jacob, Leah, and their children, she steals her father’s teraphim (small images or cult objects used as domestic deities or oracles by ancient Semitic peoples).

In the biblical narrative, Rachel’s motive for stealing the idols is not given. Was she seeking to prevent Laban from consulting them to find out which way she and her family went? Was possession of the gods in some way connected to property inheritance, as some scholars have attested? Was she stealing a blessing from her ancestors? Did she take them for their monetary value? Or leaving her homeland, did she simply wish to take with her a little piece of home, for nostalgia’s sake?

I think the most likely reason is she still believed in these gods’ power—her allegiance to the God of Jacob had not yet been firmly established—and so she stole them for protection. That’s what Hamilton imagines in her poem: that Rachel sees them as “talismans against the spite of brothers,” averting the evil Jacob’s older twin brother, Esau, wished him for his having stolen their father’s blessing that belonged to him. (According to Genesis 27:41–45, before Jacob left for Paddan-aram, Esau had vowed to kill him.)

Caught between two tricksters—her husband and her father—Rachel herself becomes a trickster. When Laban catches up with their traveling party and searches among their possessions for the stolen gods, Rachel, who’s sitting on them, lies and says she cannot get up because she’s menstruating (Gen. 31:34–35). She deceives her deceitful father to keep her deceitful husband and her son Joseph safe from Esau’s rage, as she believes the gods will act in the interests of whoever possesses them. The poem explores the ever-thickening web of deceptions woven in Jacob’s and Rachel’s families and also reminds us that Rachel, remembered now as a great Jewish matriarch, was not raised in the then-still-developing Israelite religion, nor was her turn to Yahweh necessarily immediate upon her marriage to Jacob. I hear in the poem a lament for fraternal and sororal rivalries, and a subtle sad awareness of the vulnerabilities and pressures of women in patriarchal cultures, who are bought and sold in marriage, valued primarily for their childbearing capacities, and typically forced to rely on men for survival, often suffering the consequences of men’s mistakes. (In the poem at least, Rachel’s feeling of insecurity comes from Esau’s threat of vengeance.)

Based on a lithograph by Marc Chagall, this ekphrastic poem is one of twenty-four from the unpublished chapbook Voiced by Patricia Hamilton, all inspired by biblical artworks by Chagall. Hamilton is currently looking for a publisher to take on the collection.

(Related post: “Bithiah’s defiance: Kelley Nikondeha and poet Eleanor Wilner imagine Pharaoh’s daughter”)

>> “For the Circumcision of a Small City” by Emma De Lisle, Image: The deception continues in Genesis 34; like father, like sons. This poem is based on the episode of the massacre of the men at Shechem by Jacob’s sons Simeon and Levi to avenge the rape of their sister, Dinah. Shechem, meaning “shoulder,” was the name of both the city in Canaan where the rape took place and the Hivite prince’s son who committed the rape. Jacob and his family were sojourning there, having even bought land. After sexually assaulting Dinah, Shechem wanted to make her his wife. Dinah’s brothers were disgusted by this request, but they pretended they would entertain bride-price discussions on the condition that all the males in the city be circumcised. Shechem’s father agreed, and his position as ruler meant the people obeyed. A few days after the mass circumcision, while the men were still sore, Simeon and Levi attacked with swords, killing all the males in the city. Their brothers then joined them in capturing the men’s wives and children and plundering their wealth.

Emma De Lisle’s poem is written from the perspective of a woman of Shechem, taken captive in the slaughter. The women of the city scorned the lengths Shechem was willing to go to for the homely Dinah, barely old enough to have her period. “Jacob’s silence for you” alludes to Genesis 34:5, which says that when he found out about his daughter’s rape, “Jacob held his peace” until his sons returned from the fields. If he felt grief or outrage, it’s not apparent in the scripture text. His initial response was to say and do nothing, and then to defer to his sons, who exact an outsize punishment for the crime that Jacob admits after the fact disappointed him because when word spreads, it will negatively impact the hospitality of other Canaanite cities toward them.

Stanzas 4 and 5 refer to two of Jacob’s previous deceptions: donning goatskins on his hands and neck to impersonate his hairy brother, Esau, before their blind father, so as to steal the blessing of the firstborn (Gen. 27), and altering the breeding pattern of Laban’s flocks to increase the number of spotted sheep and goats (how this is accomplished is vague and has posed difficulties for interpreters) and so enrich himself, as the spotted animals were his agreed-upon wage (Gen. 30:25–43). The implication of this mention is, I think, that men will take what they feel is owed to them, whether by guile or force.

Sometimes women participate in this violence. The poetic speaker wonders whether Dinah will force her or the other captive women to bear children for her (future husband’s) family line, just as her mother, Leah, had used her slave, Zilpah, when her own womb had closed.

“The city bled one way // or another, before your brothers took interest,” the speaker says. Sexual violence was not new to them. The last sentence suggests that Dinah was not the only female victim of the lustful Shechem’s assault—the women of the city paid a price too, seeing their husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons murdered in retaliation and themselves taken prisoner.

+++

ORATORIO: The Book of Romans by Emily Hiemstra (2019): Consisting of musical settings of select passages from the apostle Paul’s letter to the Romans, this piece for SATB soloists, choir, and string orchestra was commissioned by Grace Centre for the Arts, a ministry of Grace Toronto Church, where it premiered October 22, 2019. (Hooray for churches that commission new art!) Read a statement from the composer on the Deus Ex Musica blog. The performers are Meghan Jamieson (soprano), Rebecca Cuddy (alto), Asitha Tennekoon (tenor), Graham Robinson (baritone), Lyssa Pelton (violin), Amy Spurr (violin), Emily Hiemstra (viola), and Lydia Munchinsky (cello).

Here is the video time stamp for each of the eight movements:

- 0:18: i. Who Has Known the Mind of the Lord? (Rom. 11:33–36)

- 3:56: ii. His Eternal Power and Divine Nature (Rom. 1:20)

- 6:04: iii. None Is Righteous (Rom. 3:10–12, 17–18)

- 10:39: iv. For All Have Sinned (Rom. 1:16; 3:23–26)

- 14:08: v. There Is Now No Condemnation (Rom. 8:1, 29, 31–32)

- 19:39: vi. Those Who Were Not My People (Rom. 9:25–26)

- 24:19: vii. How Beautiful (Rom. 10:14–15)

- 28:12: viii. May the God of Hope (Rom. 15:13)

(Related post: “Book of Romans album by Psallos”)