Following the popularity of last year’s “25 Poems for Christmas,” I’ve decided to publish a brand-new installment, and will perhaps make this a yearly tradition! All the selections can be read online—just follow the links.

Despite the pithy title of this post, not all the poems are “Christmas” poems, strictly speaking, but rather they encompass the season of Advent too, as well as Epiphany. Advent is a four-week season leading up to Christmas that is characterized by a mood of longing and expectation; it is oriented not only toward Jesus’s first coming but also toward his second. Christmas, of course, celebrates the birth of Jesus, the Word of God made flesh. And Epiphany, on January 6, commemorates the visit of the magi to the crib, representing God’s self-revelation to the wider world.

Each poem is accompanied by a micro-commentary or short descriptive blurb, which I suggest you read after reading the poem itself. There’s a benefit to first entering a poem without having any context—then after registering your initial impressions and questions, to consider another person’s framing or analysis or highlights, and reread. And then a third time! Each reading can potentially reveal new meaning.

1. “Haiku for an Advent Calendar” by Richard Bauckham: Church services during Advent tend to focus on messianic prophecies from the Hebrew Bible, rumblings of a coming savior. In this sequence of twenty-four haiku, Richard Bauckham pulls a detail from each book of the Jewish scriptures, finding anticipations of Christ. For example, Isaiah: “In the wilderness / a voice cries for centuries / seeking an echo.” Or Job: “God answered Job but / not his question. Maybe he / will do that again.”

Source: Tumbling into Light: A Hundred Poems (London: Canterbury Press Norwich, 2022) | https://richardbauckham.co.uk/

2. “How Christ Shall Come” (anonymous): The cosmological Christ blew in from the four cardinal directions, coming as lover, knight, merchant, and pilgrim. So says this fourteenth-century Middle English lyric, rich in metaphor, compiled in a book of preaching aids and sermons by John Sheppey (d. 1360), bishop of Rochester. (It is unclear whether he is the author of the poem.) The great medieval literature scholar Carleton Brown gave it the title “How Christ Shall Come” in his landmark Religious Lyrics of the XIVth Century (1924), and Grace Hamman brought it to my attention recently in her wonderful monthly Substack, Medievalish, providing a modern English translation and commentary.

Source: Merton College MS 248, fol. 139b. Public Domain.

3. “Hawk Lies Down with Rabbit” by Seth Wieck: What would it look like for death to no longer have dominion in the animal world? Grappling with Isaiah’s end-time vision of a peaceable kingdom void of predation, this poem describes in graphic terms a bird of prey making its kill, feeding on flesh, and wonders how a hawk could still be itself with rewired impulses. Hear the author read and provide context for the poem on the Reformed Journal Podcast.

Source: Reformed Journal, January 31, 2023 | https://www.sethwieck.com/

4. “john” by Lucille Clifton: Written in the voice of John the Baptist, this poem is part of an extraordinary sixteen-poem sequence titled “some jesus,” which features a range of biblical characters. In her retelling of his ministry as forerunner to the Messiah, Lucille Clifton casts John as a Black Baptist preacher, preparing his listeners to receive the one who “com[es] in blackness / like a star.” Clifton’s larger body of work would suggest that “blackness” here is multivalent, describing what Jesus comes into and as: the word suggests the darkness of the world that Christ entered, on the one hand, but also functions as a positive racial identifier. In Clifton’s revisioning, Christ comes as a Black man, wearing “a great bush / on his head”—which, again, could be read as an Afro, and/or as a mystical reference to the site at which God revealed himself to Moses in the Sinai desert. Luminous with truth, Christ comes, “calling the people brother.”

Source: Good News About the Earth (New York: Random House, 1972); compiled in The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton (Rochester: BOA Editions, 2012)

5. “Christmas Mail” by Ted Kooser: Every December the story of an ancient birth comes alive again in couriers’ mailbags, in tin boxes at the ends of driveways, on mantels and fridges. This poem honors those postal workers who deliver good tidings in the form of Christmas cards, the magic spilling out the envelopes to make even the most tiresome routes sparkle a bit.

Source: Poetry Foundation | https://www.tedkooser.net/

6. “December 25” by George MacDonald: Through the mid-nineteenth century, denominations influenced by the Reformed tradition, including the Church of Scotland in which George MacDonald was raised, typically did not observe Christmas, the rationale being that no one day should be thought of as holier than any other. But in his book-length dramatic poem Within and Without, MacDonald refers to December 25 as “this one day that blesses all the year”—and in this seven-liner from his Diary of an Old Soul, he describes Christmas as a gleaming blue sapphire, a structural center around which all the other jewels of the church calendar are oriented.

Source: The Diary of an Old Soul (privately published, 1880). Public Domain.

7. “On a Cardinal Climbing Down a Manhole to Restore Power to 400 Homeless People” by Michael Stalcup: On May 11, 2019, Cardinal Konrad Krajewski, the papal almoner (Pope Francis’s special appointee to distribute charity), crawled into a manhole and broke a police seal to personally restore power to a homeless shelter in Rome whose electricity had been shut off due to its failure to pay its bills. The shelter was occupied by some 450 people at the time, 100 of them children, who had been without electric light, hot water, and refrigeration for nearly a week. In this poem, which can be read Christologically, Michael Stalcup celebrates this defiant humanitarian act that brought light to a people living in darkness.

Source: Commonweal, April 2020 | https://www.michaelstalcup.com/

8. “Incarnation” by Amit Majmudar: “Inheart yourself, immensity. Immarrow, / Embone, enrib yourself.” So begins the five-poem sequence “Seventeens.” Musical and witty, this first poem is a plea to the great I AM to take on a body and “be all we are, and all we aren’t.”

Source: Heaven and Earth (West Chester, PA: Story Line Press, 2011) | http://www.amitmajmudar.com/

9. “The Lord Is with Thee” by Micha Boyett: Written in 2010 as the third in a five-poem sequence commissioned by John Knox Presbyterian Church in Seattle, this poem centers on the Visitation episode described in Luke 1:39–58. It’s about Mary finding belonging in God’s story, especially through the companionship of her elder cousin Elizabeth, who has nurtured Mary’s faith since infancy and continues to do so in this her moment of crisis. “How easily she spoke of God, / as if he were a neighbor, a fish vendor on the street,” Mary admires. Elizabeth supports Mary physically, emotionally, and spiritually, holding her hair back as she vomits, protecting her from vicious rumors, affirming the work of God in her life, and accompanying her at the start of this wild path God has set them both on.

Source: The By/For Project | https://www.michaboyett.com/

10. “Our Lady” by Mary Elizabeth Coleridge: The great-grandniece of the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Mary Elizabeth Coleridge (1861–1907) grew up in a home visited by family friends Alfred Lord Tennyson, Anthony Trollope, John Ruskin, and Robert Browning, among others. In this poem she marvels at how God chose the common-born Mary for such a task as mothering the Christ, singing along with Mary’s Magnificat about how God raises up the lowly.

Source: Fancy’s Following (privately published, 1896). Public Domain.

11. “Traveling Man” by Marjorie Maddox: With his pregnant wife alongside, Joseph plods down south to Bethlehem, “convinced of the predestined / roll of dice chrismated with Miracle.” An epigraph from a Leonard Cohen song sets the tone.

Source: Begin with a Question (Brewster, MA: Paraclete, 2022) | http://www.marjoriemaddox.com/

12. “Sonnet in the Shape of a Potted Christmas Tree” by George Starbuck: This charming shape poem contrasts the extravagance of our popular celebrations of Christmas with the poverty of the first-century event it marks. The first half describes the furious wind of decorative activity that uproots evergreens from their natural habitats to bring them indoors and deck them with baubles and ribbon. I don’t know how to interpret “no scapegrace of a sect,” but “Daughter-in-Law Elect” refers to a duet from the Gilbert and Sullivan opera The Mikado. The turn comes with “a son born / now / now,” the latter two lines styled as the visible trunk of the tree; here the scene shifts to the simple stable of old, where Mary lies “spent” next to her newborn along with a cow and donkey, a sole “firework” guiding the magi and us all to the spot.

Source: The Works: Poems Selected from Five Decades (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2003)

13. “Christmas (I and II)” by George Herbert: George Herbert (1593–1633) is one of the most celebrated poets of the English language. In part 1, a sonnet, of this two-part poem, he imagines himself a weary traveler who chances upon a humble inn where he unexpectedly finds his Lord, the infant Christ. It’s the inn of Bethlehem. Having then received rest from Christ his host, in the closing couplet he expresses his desire to reciprocate—to offer his own soul, lowly though it is, as a residence for Christ, praying that God first adorn it to make it hospitable. In the second part of the poem, Herbert uses a metaphysical conceit (extended metaphor) comparing his soul to a shepherd whose flock of thoughts, words, and deeds pastures on God’s word and who, like the shepherds of Bethlehem, sings glory to God. His shepherd-soul seeks eternal daylight, which he finds in the Son/sun, whose beams so intertwine with his song that the beams sing and his song shines.

Source: The Temple: Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations (Cambridge, 1633). Public Domain.

14. “Descending Theology: The Nativity” by Mary Karr: The physicality of childbirth, from the contractions (which pierce the Virgin like a star, Karr writes) to the bodily fluids, is heavily featured in this poem. Jesus emerges from his mother “a sticky grub” with a “lolling head” and “sloppy mouth” that seeks out her breast for food. And as she feeds him physically, he feeds her spiritually. Then he falls asleep. His first nap, Karr writes, is a foretaste of the sleep of death he will eventually come to taste. But for now, he wakes up crying—as all babies do.

Source: Sinners Welcome (New York: HarperCollins, 2006) | https://www.marykarr.com/

15. “from spiralling ecstatically this” by E. E. Cummings: What a fantastic opening line! The heavenly spheres whirling, twirling, down into the “proud nowhere”—Bethlehem—“of earth’s most prodigious night.” Heretofore living in mundanity, the domestic animals, hungry for miracle, for newness, are vouchsafed to be witnesses of this supernatural event, before which they kneel “humbly in their imagined bodies.” Overhead floats the “perhapsless mystery of paradise,” a phrase suggesting that heaven is beyond human understanding but not without certainty; it’s a declarative reality, not subjunctive, even if it can’t quite be put into words. Mary herself has no words—she silently, knowingly smiles, while the created world erupts in song around her. The “mind without soul” is a reference to Herod, who seeks to snuff out this new life, but to no avail.

The omission of spaces after punctuation marks (e.g., “a newborn babe:around him,eyes”) is not a mistake; that’s how E. E. Cummings liked it. Scholars say it’s to create a faster rhythm, but in this poem I don’t think that choice is as effective, as pauses and slow savoring seem more appropriate to its contemplative mood.

Source: Atlantic, December 1956; compiled in E. E. Cummings: Complete Poems, 1904–1962, exp. ed., ed. George J. Firmage (New York: Liveright, 2016)

16. “How the Natal Star Was Born” by Violet Nesdoly: Narrated by the angel Gabriel, this poem imaginatively describes heaven’s nervously awaiting the birth of Jesus during the nine months following Gabriel’s dispatch to Mary, and then busting out in celebration when at last they hear his infant-cry. When his Son is born, instead of cigars, the Father passes out trumpets to his company of friends, who sound them all the way to Bethlehem’s fields, and pops open a bottle of champagne whose bubbles spray far and wide.

Source: Calendar (Surrey, BC: SparrowSong Press, 2004) | https://violetnesdoly.com/

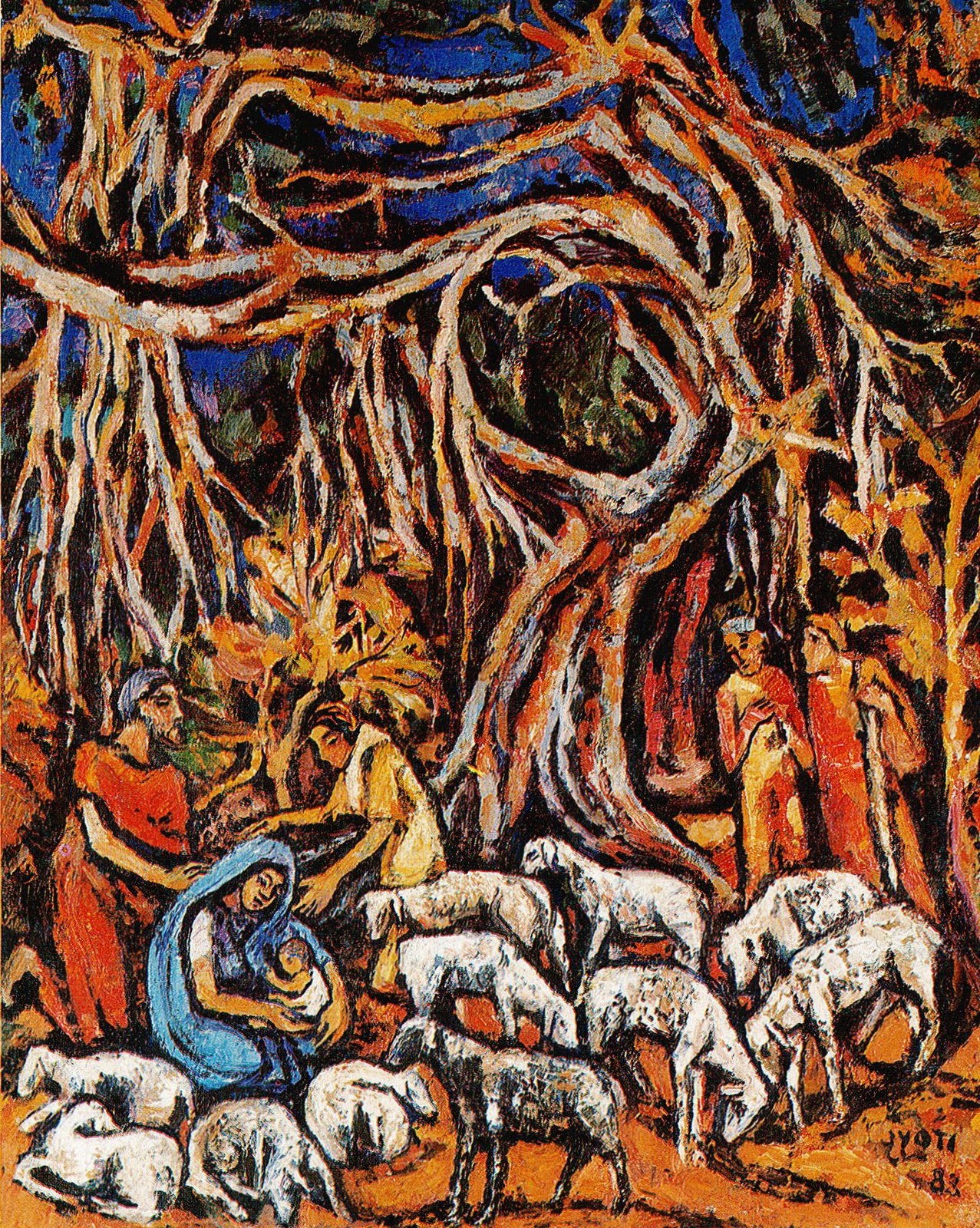

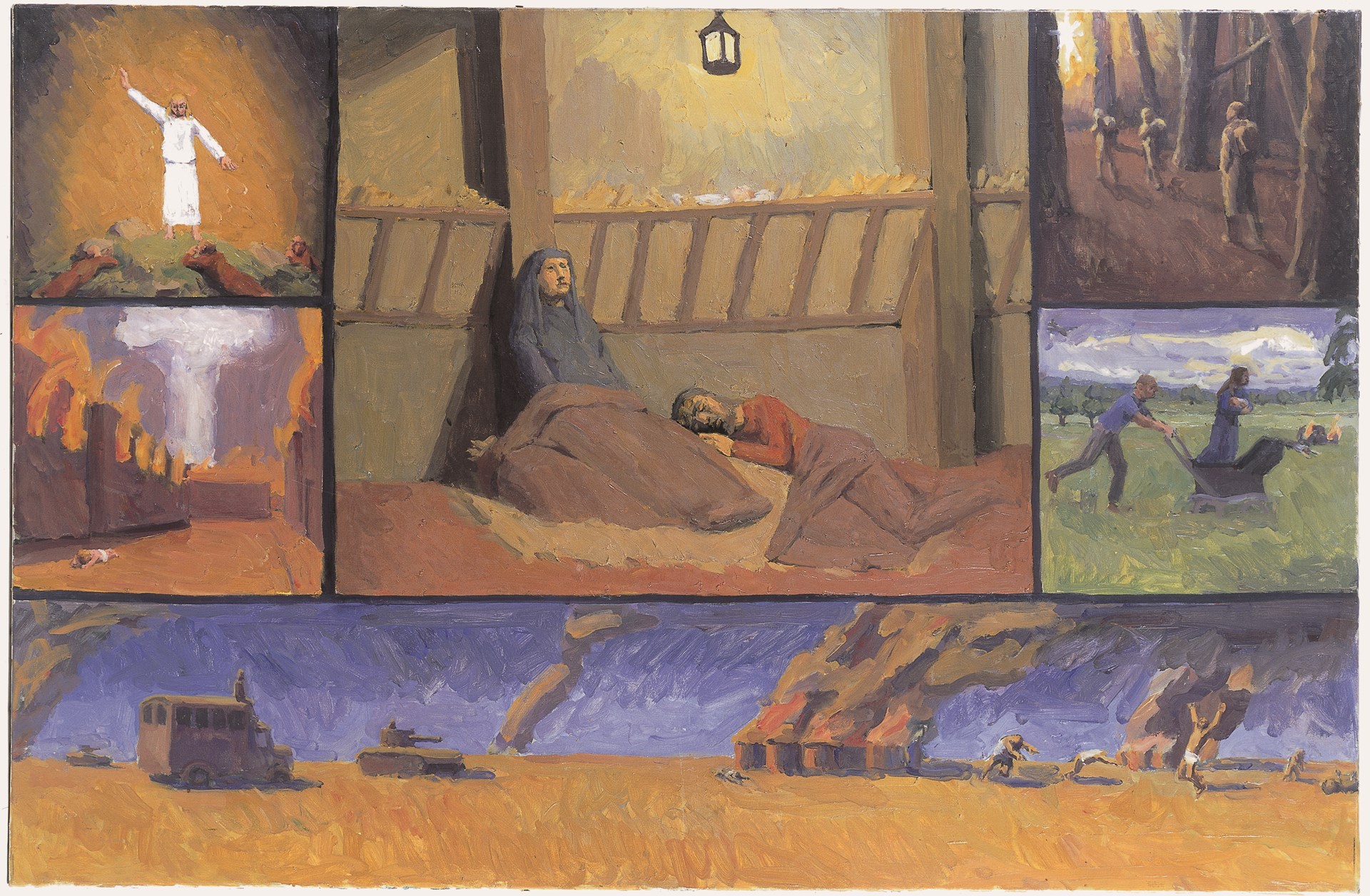

17. Sections 9–10 of “The Child” by Rabindranath Tagore: Hinduism was the religion of Rabindranath Tagore’s birth and upbringing, but he also held deep respect for Jesus Christ. (For more on the influence of Christianity on Tagore’s thought and writing, see chapter 4 of Rabindranath Tagore and Interfaith Dialogue by Manas Kumar Ghosh [DMin thesis, Charles Sturt University, 2010].) “The Child” is a free-verse poem that Tagore wrote in English in 1930 after seeing a passion play in Germany and then translated into Bengali in 1932 with the title “Sishutirtha” (Pilgrimage to Childhood). In it a “Man of faith” gathers people from all walks of life to join him on a “pilgrimage of fulfilment,” to “struggle [through the dark] into the Kingdom of living light.” Initially met with enthusiasm, the Man later becomes a target of the people’s anger and distrust, and they kill him. Disorientation ensues. But a man in the crowd is able to rally the others to repent and resume their quest, following the spirit of “the Victim.”

The final two sections, 9 and 10, are the selection I’ve chosen. (Scroll right to read the last.) At “the first flush of dawn,” when the time is ripe, the pilgrims arrive at a thatched hut in a palm grove, where they finally meet the eternal Light they’ve been seeking: “the mother . . . seated on a straw bed with the babe on her lap, / . . . the morning star.” Here is the Child of the title, humanity’s redeemer.

Source: The Child (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1931)

18. “Love’s Bitten Tongue (11)” by Vassar Miller: This poem, “You, my God, lonesome man, Love’s bitten tongue,” is from a crown of twenty-two sonnets, a type of sequence in which the last line of each sonnet is repeated as the first line of the next, but each time with a new twist of syntax and sense. The crown as a whole expresses the poet-speaker’s struggle against her ego, and her desire for Christ (whom she gives such an evocative name in the title!). In this particular sonnet she describes waiting at the edge of her bed every Christmas Eve as a child in anticipation of both Santa’s arrival with gifts and the holy mystery of Christ’s birth, an admixture of sacred and profane longings that fill her still as an adult.

Source: Struggling to Swim on Concrete (New Orleans: New Orleans Poetry Journal Press, 1984); compiled in If I Had Wheels or Love: Collected Poems of Vassar Miller (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1991)

19. “Gloria in Profundis” by G. K. Chesterton: G. K. Chesterton’s poems are of variable quality, but this one is brilliant, emphasizing God’s descent from the rich heights of heaven into an obscure cave in a simple town. “Glory to God in the lowest!” it exclaims, a clever inversion of the angels’ song to the shepherds in Luke 2:14. The poem was originally published in a 1927 Christmas pamphlet with wood engravings by Eric Gill. The Latin title translates to “Glory in the Depths.”

Source: Gloria in Profundis by G. K. Chesterton (Ariel series pamphlet) (London: Faber and Gwyer, 1927); compiled in The Spirit of Christmas (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1985)

20. “Silent Night” by Bonnie Bowman Thurston: Rev. Dr. Bonnie Thurston invokes a tradition that says the night of Christ’s birth, there was a whole hour in which time stood still and all was silent. What a fascinating legend! Thurston told me its origin is northern European, said she remembers reading it in some scholarly Celtic studies; I wasn’t able to locate any such mentions, but the second-century Protoevangelium of James, chapter 18, probably written in Egypt or Syria, does describe everything momentarily freezing in place around Joseph as he steps out to find a midwife for Mary. Anyway, the poem ends with a striking metaphor! Word, flesh: fire. (Reminds me of this digital artwork by Scott Erickson.)

Source: Remembering That It Happened Once: Christmas Carmen for Spiritual Life All Year Long, ed. Dennis L. Johnson (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2021)

21. “After Luke 2:19” by Michelle Ortega: When the shepherds recounted to Mary what the angels had told them in the fields about Jesus being the promised Messiah, “Mary treasured all these words and pondered them in her heart,” Luke narrates in his Gospel. Poet Michelle Ortega expounds on this verse, emphasizing the relationship of Mary’s body to her son’s from conception to birth and now postpartum—an intimacy known well by mothers across the centuries. As wondrous as it was to be part of a cosmic story writ large in the skies, Ortega suggests that Mary treasured just as much as the grand pronouncements those small moments of being just an ordinary mama.

Source: Mary, Mary: Contemporary Poets and Artists Consider Mary (Arlington, VA: St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, 2021), a free e-book accompanying an art exhibition

22. “Christmas: 1924” by Thomas Hardy: “We the civilized world have given Christianity a fair trial for nearly 2000 years, & it has not yet taught countries the rudimentary virtue of keeping peace,” lamented the British novelist and poet Thomas Hardy (1840–1928) in a letter to Florence Henniker dated February 25, 1900, during the Boer War. World War I only increased his cynicism, which is on display in this sour little epigram that opens with an ironic quotation of the angels’ proclamation to the shepherds the night of Jesus’s birth.

Source: Winter Words in Various Moods and Metres (New York: Macmillan, 1928). Public Domain.

23. “Eating Baklava on New Year’s Eve” by Anya Krugovoy Silver: Poet Anya Silver (1968–2018) reads a spiritual benediction in her piece of baklava, layered and sweet and consumed on the eve of a new year.

Source: Second Bloom (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2017)

24. “A Ballad of Wise Men” by George M. P. Baird: Jesus so often confounds the wisdom of the wise, starting with his birth. With gentle humor and in iambic rhythm and rhyme, this poem celebrates the simple access we all have to Christ.

Source: Rune and Rann (Pittsburgh: Aldine Press, 1916). Public Domain.

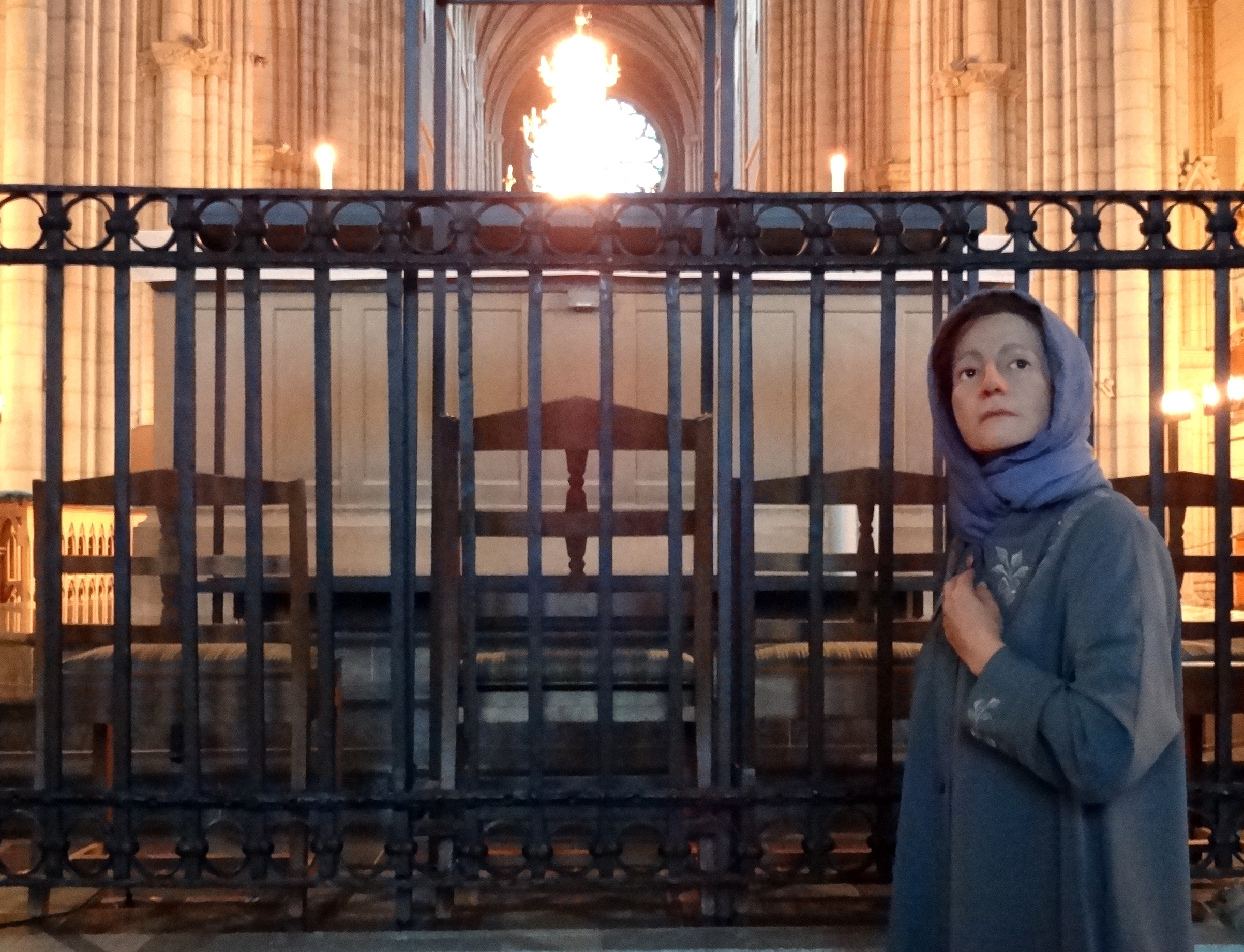

25. “Excrucielsis” by Hannah Main-van der Kamp: Originally published at ArtWay.eu as a response to the contemporary Romanian sculpture The Spring by Liviu Mocan, this poem alternates between the weary journeying toward truth of one of the biblical magi and that of a modern-day seeker similarly “longing for / the something more.” It can be a trudge, finding the Light—it involves risk, a willingness to follow the signs, and the tenacity to hold on to your “vision burden,” “clutch[ing] the weight” of it all the way over rough and varied terrain. But the epiphanic moment awaits, to sound like a trumpet blast. The title of the poem is a neologism combining the words “excruciating” and “excelsis” (Latin for “the heights”); “every excelsis contains something excruciating, that’s how we get to genuine excelsis,” the poet told me in an email. Read a related prose reflection by Main-van der Kamp here.

Source: The Slough at Albion (Victoria, BC: Ekstasis Editions, forthcoming)

Disclosure: This post contains Amazon affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission from qualifying Amazon purchases originating from clicks on this site.