BALTIMORE-ANNAPOLIS CONCERTS:

This November near where I live in Maryland there are at least two concerts by Christian artists I’d like to invite you to:

>> Matthew Clark, November 1, 2025, Crownsville, MD: The Eliot Society, an organization I volunteer with, is hosting Matthew Clark, a singer-songwriter from Mississippi, for an evening of music and stories this Saturday. Tickets are $10; wine, coffee, and refreshments will be served. Here’s Clark’s song “Ordinary Artists”:

>> Ordinary Time, November 22, 2025, St. Moses Church, Baltimore: Longtime friends Peter La Grand (Vancouver), Jill McFadden (Baltimore), and Ben Keyes (Southborough, Massachusetts) make up the acoustic folk trio Ordinary Time. They’re performing a free concert at McFadden’s church in a few weeks, which will be followed by Q&A around the role of music in the communal life of the church. Here’s their song “I Will Trust (Isaiah 12)”:

+++

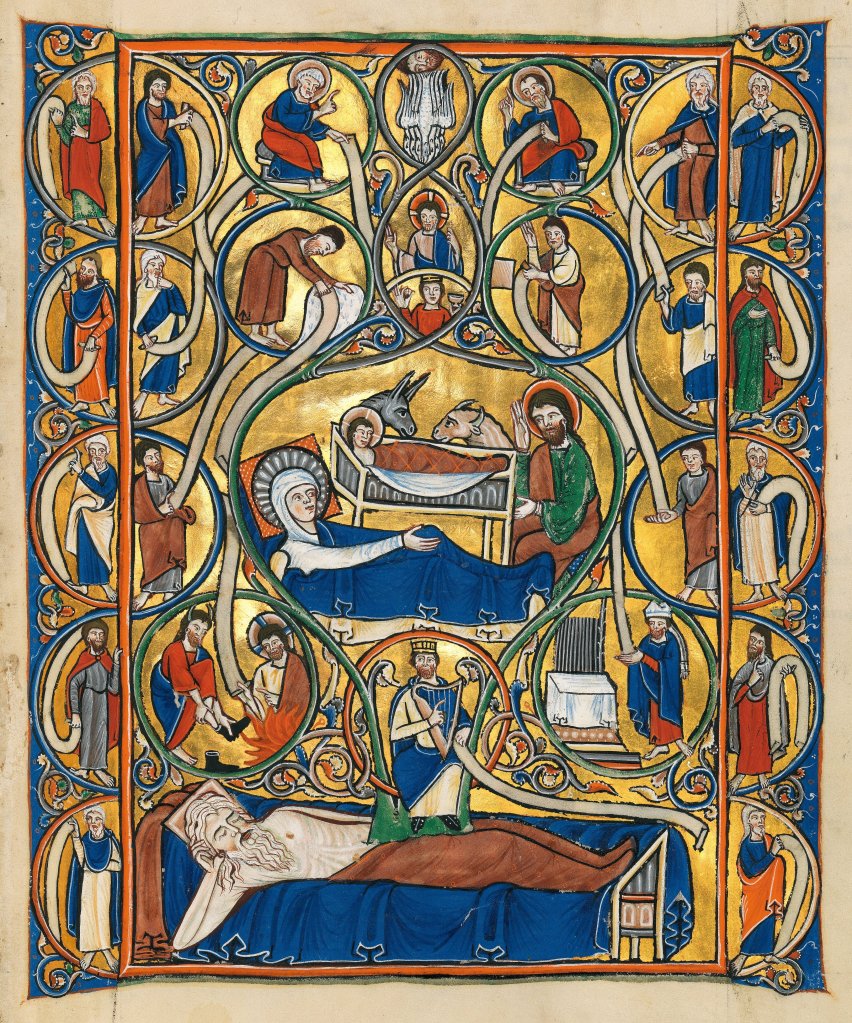

BOOK REVIEW: “How Does Your Garden Grow? Grace Hamman on Medieval Conceptions of Virtue and Vice” by Victoria Emily Jones, Mockingbird: I reviewed Grace Hamman’s latest book, Ask of Old Paths: Medieval Virtues and Vices for a Whole and Holy Life, for Mockingbird. Check it out!

+++

FREE AUDIOBOOK: An Axe for the Frozen Sea: Conversations with Poets about What Matters Most by Bel Palpant: “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us,” Franz Kafka wrote in a letter to his friend Oskar Pollak in 1904. That quote is the source of the title of Ben Palpant’s new book, one of my favorites of this year. An Axe for the Frozen Sea is a collection of one-on-one interviews Palpant conducted with seventeen acclaimed poets of faith, exploring the human experience, especially everyday joys and struggles, and the writing life. Featured poets include Scott Cairns, Marilyn Nelson, Robert Cording, Li-Young Lee, and Jeanne Murray Walker. I was really compelled by the conversations.

An Axe for the Frozen Sea is available for purchase in print, but it also kicked off the new podcast Rabbit Room Press Presents, serialized audiobooks of select titles from the publisher. All the book’s content, read by the author, can be listened to for free in this format. Highly recommended!

+++

ARTICLE: “Bone chapels and their strange art” by Lanta Davis, Christian Century: If my last blog post piqued your interest in Christian bone chapels, you’ll want to read this article Lanta Davis wrote last November about her visit to the crypt of Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini in Rome. With a scythe-wielding skeleton overhead and arches, garlands, chandeliers, and mock clocks made of human bones, you’d be forgiven for thinking you mistakenly wandered into a haunted house. But in fact this is a sacred space, its unusual decoration the devotional labor of a seventeenth-century friar. Davis reflects on how the bone installations transform the ugliness of death into something beautiful, rearranging death into surprising forms—such as a skull with butterfly wings made from shoulder blades—that culminate in the Crypt of the Resurrection.

+++

SONG: “Bones” by Mark Shiiba: The title track of Mark Shiiba’s debut album from last year references the placard that greets visitors to Rome’s Crypt of the Three Skeletons (see previous roundup item): “What you are now we used to be; what we are you will be.” This saying was a common memento mori, which I first learned when studying Renaissance art in Florence as a junior in college: Io fu già quel che voi siete, e quel chi son voi ancor sarete, reads the inscription above the fictive cadaver tomb that Masaccio painted inside Santa Maria Novella.

Shiiba’s song is jaunty in tone, and when he shared an excerpt on Instagram, he set it to the similarly sprightly animated short The Skeleton Dance (1929) by Walt Disney, which is based on medieval “danse macabre” imagery. Perhaps that seems to you unbefitting of such a serious subject as death—but since its inception, the church has proclaimed Christ’s ultimate defeat of death. “Where, O death, is your victory?” the apostle Paul taunts. “Where, O death, is your sting?” Death is lamentable, but it’s not the end of the story. The playfully arranged “bones at the bottom of a church in Rome” anticipate the resurrection of our bodies on the last day.