One day

[. . .]

God

will come forward

to settle the conflicts between us

finally the one

true witness

even the finality of holocaust

will melt away

like lowland snow

the military hardware

translated into monkey bars

where children play

the hardened postures

crumbled

like ancient statues

children will wave through the gunholes

of tanks

rumbling off to the junkyard

people will find hands

in theirs

instead of guns

learn to walk

into their gardens

instead of battle

Oh House of Israel

let’s walk in the sunlight ways

of his presence

—Isaiah 2:2–5, translated by David Rosenberg in A Poet’s Bible: Rediscovering the Voices of the Original Text (New York: Hyperion, 1991)

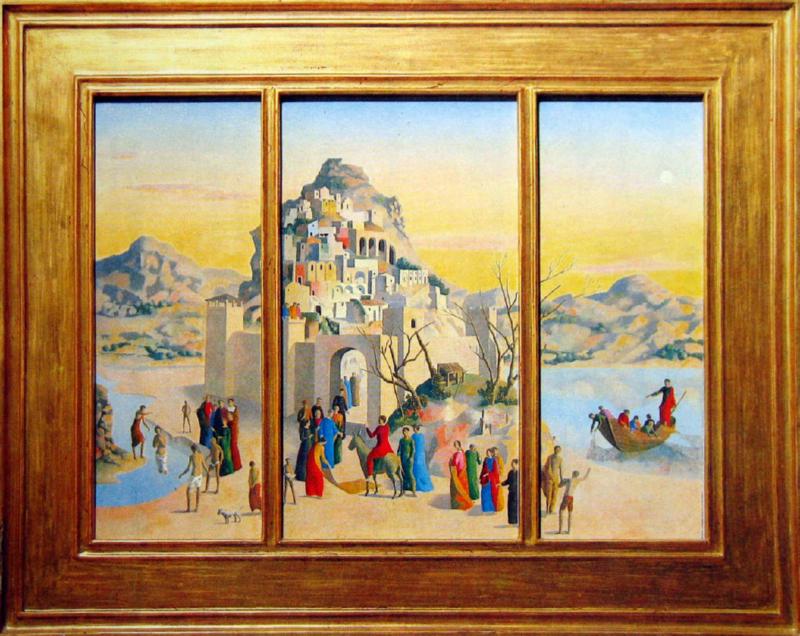

LOOK: Isaiah’s Vision of Eternal Peace by Mordecai Ardon

Born in 1896 to a Jewish family in the village of Tuchów in what is today Poland, Mordecai Ardon studied art in Germany under Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, he moved to Jerusalem, becoming a teacher in 1935 at Palestine’s chief art academy, the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts, which he directed from 1940 to 1952. Known for their vibrant tones and stirring rhythms, Ardon’s paintings often explore the connections between the visible and the invisible and reflect his interest in mysticism and antiquity.

From 1982 to 1984 Ardon carried out a commission by the National Jewish University and Library (now the National Library of Israel) in Jerusalem to develop a monumental triptych of stained glass. His painted designs were translated into the medium of stained glass by the French master glazier Charles Marq, a frequent collaborator of Marc Chagall’s. The result is titled Isaiah’s Vision of Eternal Peace.

The left panel illustrates Isaiah 2:2–3:

In days to come the mountain of the LORD’s house shall be established as the highest of the mountains and shall be raised above the hills; all the nations shall stream to it. Many peoples shall come and say, “Come, let us go up to the mountain of the LORD, to the house of the God of Jacob, that he may teach us his ways and that we may walk in his paths.”

Winding like roads, the white bands contain the boldfaced line in various languages—I can detect English, Russian, Polish, Arabic, Latin, and French—representing the peoples of the world streaming to Jerusalem.

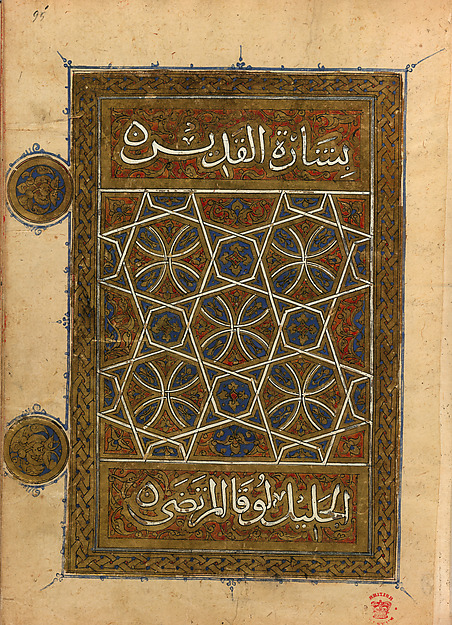

The center panel depicts a merging of the earthly and heavenly Jerusalems. At the bottom stand the city walls, made up of the seventeen sheets of parchment that comprise the Great Isaiah Scroll from Qumran, dating to around 100 BCE. Floating above are Kabbalistic symbols, including the Tree of the Sefirot, signifying the Divine Presence. There are also several Hebrew texts from Jewish history that I can’t identify.

The right panel visualizes the fulfillment of Isaiah 2:4: “. . . they shall beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation; neither shall they learn war any more.” All the machinery of war—tanks and fighter jets, guns and bullets—lies in a garbage heap at the base, and shovels emerge overhead as the weapons are transformed into farming tools.

This glasswork covers an entire wall of the old National Library of Israel building on the Givat Ram campus of Hebrew University. The library moved into a new building in October 2023, situated between the Knesset and the Israel Museum in the heart of Jerusalem. But Ardon’s window remains in its original building at HUJI, which has become a multipurpose space.

LISTEN: “Lo Yisa Goy (Study War No More)” (ֹא יִשָּׂא גוֹי) | Traditional Jewish folk song, arr. Linda Hirschhorn and Fran Avni | Performed by Vocolot, on Behold! (1998)

לֹא יִשָּׂא גוֹי אֶל גוֹי חֶרֶב

לֹא יִלְמְדוּ עוֹד מִלְחָמָה(Transliteration:

Lo yisa goy el goy cherev

Lo yilmadu od milchama)(Translation:

Nation will not take up sword against nation

Nor will they train for war anymore)And into plowshares [they’ll] beat their swords

Nations shall learn war no more

The lyrics of this traditional Jewish antiwar song come from the original Hebrew of Isaiah 2:4, a text held sacred by both Jews and Christians. The song looks with prayerful hope toward the day when global peace will be a reality.

If this is the glorious end state to which we all are headed, the future that God has envisioned and charted for us, then why do we participate in violence now? When governments try to control people through violence, and those people respond with violence, that response only provokes violent retaliation, and so the cycle continues on and on—militancy and death. The line between aggressor and defender becomes blurred. We’ll never get closer to the Isaiah 2 ideal by asserting ourselves with weapons.

May the people of God be a people who refuse violence even when the state commands it, even when we’ve been hit tremendously hard and the urge for payback is intense. May we not become what we fear, inflicting terror because we have been terrorized. And may God bring peace and healing to people and nations who have been victims of war; so too perpetrators of war. To those just trying to survive and be free in this fallen world as best they know how.

The first chapter of Isaiah, which precedes the famous “swords into plowshares” chapter, contains this word from the Lord to his people:

When you stretch out your hands,

I will hide my face from you;

even though you make many prayers,

I will not listen;

your hands are full of blood.

Wash yourselves clean, make yourselves clean;

remove the evil of your doings

from before my eyes;

cease to do evil,

learn to do good;

seek justice,

rescue the oppressed,

defend the orphan,

plead for the widow.—Isaiah 1:15–17

So let us renounce our vindictiveness and “wash ourselves clean.” And then let us sing this song (1) as a prayer that the Messiah, whom Christians recognize to be Jesus of Nazareth, would come to actualize this beautiful vision of peace, but (2) also as a pledge, committing ourselves to the path of life—to, in the words of the apostle Paul, “overcom[ing] evil with good” (Rom. 12:21).

I like Vocolot’s “Lo Yisa Goy” arrangement best; it has a celebratory mood, as if the coming peace is in sight. But what follows is a handful of others that carry more of a lamentful tone, which is also appropriate as we consider the persistence of war and how short we fall of God’s plan for human flourishing that’s never at the expense of others.

For harp and voice by Estela Ceregatti of Brazil, 2020:

A cappella by the American Midwest female vocal trio Rock Paper Scissors, 2010:

For strings, by La Roche Quartett from Germany, 2018:

A virtual choir under the direction of Andrea Salvemini, 2020:

The last performance employs an increasing number of instruments as the song progresses: guitar, recorder, keyboard, cello, percussion, and accordion. It also includes steps to an Israeli circle dance performed by participants in isolation because this was during the days of COVID quarantines; elsewhere online you can find communal performances where the circle is closed.

Some versions add these two lines as a verse, adapted from Micah 4:4:

And every man ’neath his vine and fig tree

Shall live in peace and unafraid