ORIGINAL MIDDLE ENGLISH:

Loue me brouthte,

& loue me wrouthte,

Man, to be þi fere.

Loue me fedde,

& loue me ledde,

& loue me lettet here.

Loue me slou,

& loue me drou,

& loue me leyde on bere.

Loue is my pes,

For loue i ches,

Man to byƷen dere.

Ne dred þe nouth,

I haue þe south,

Boþen day & nith,

To hauen þe,

Wel is me,

I haue þe wonnen in fith.

MODERN ENGLISH TRANSLATION:

Love me brought,

And love me wrought,

Man, to be thy fere. [companion]

Love me fed,

And love me led,

And love me fastens here.

Love me slew,

And love me drew,

And love me laid on bier.

Love’s my peace;

For love I chose

To buy back man so dear.

Now fear thee not;

I have thee sought

All the day and night.

To have thee

Is joy to me;

I won thee in the fight.

Trans. Victoria Emily Jones

This medieval passion lyric is from the Commonplace Book of John of Grimestone, compiled in Norfolk, England, in 1372 and owned by the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh. It was transcribed by Carleton Brown in Religious Lyrics of the Fourteenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924), page 84.

(Related post: “Undo thy door, my spouse dear”)

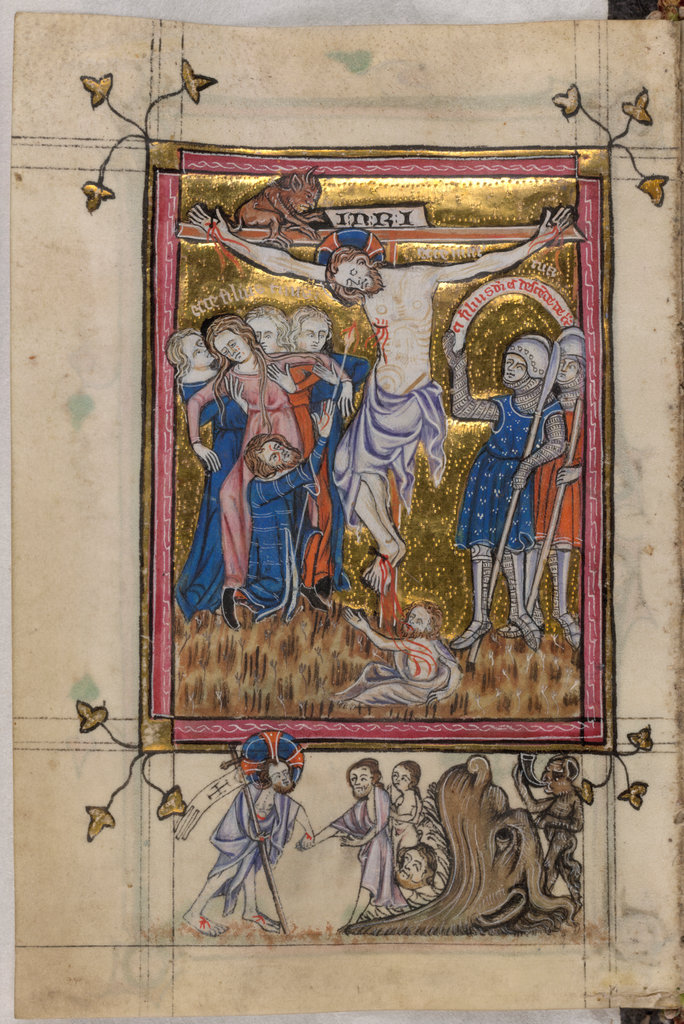

In the poem, Christ addresses humankind from the cross, professing his great love for her. He was begotten in love by the Father, and it’s love that brought him to earth. Love nourished and guided him, and for love he stayed the difficult course, all the way to the end. Satan had stolen Christ’s beloved, and to win her back, Christ went into battle, to redeem her who was rightfully his. His decisive move: spreading out his arms across a wooden beam, so as to embrace the world, and submitting to being nailed there.

He died for love of his lady. Love is what drew him to and secured him to that cross, what kept him there when the physical and emotional agony begged he desist. And because of his persistence in seeking us, his courageous endurance as the enemy assailed, he attained ultimate victory. “Well is me!” (Blessed am I), he exclaims, “for you are mine and I am yours.” Let nothing stand between.

Katharine Blake, the founder and musical director of Mediæval Bæbes, wrote a setting of “Love Me Broughte,” in medieval style, for the group’s 1998 album Worldes Blysse. Sweet and vigorous, it features, besides voices, a zither, pipe, recorder, tambourine, and drums.

Did you enjoy this poem? For more like it, come on out on November 23 to “Christ Our Lover: Medieval Art and Poetry of Jesus the Bridegroom,” a lecture by Dr. Grace Hamman that I’ve organized for the Eliot Society in Annapolis. Learn some of the ways Christian preachers, poets, theologians, mystics, and artists in the late Middle Ages, both male and female, conceptualized Christ’s passionate love, drawing from the Song of Songs, courtly love poetry, and more—often in quite imaginative ways!