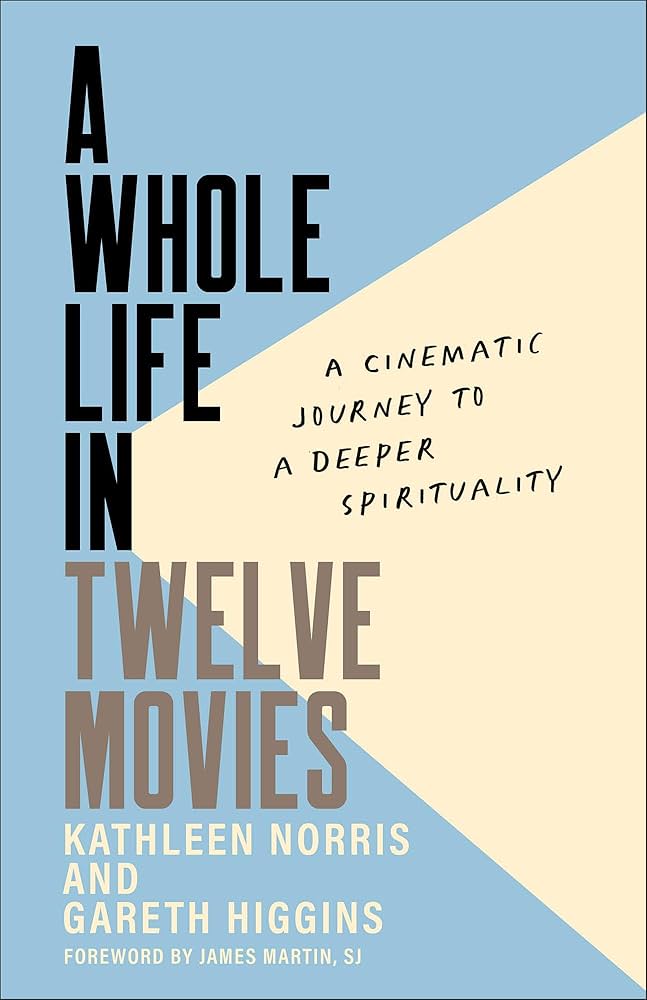

NEW BOOK: A Whole Life in Twelve Movies: A Cinematic Journey to a Deeper Spirituality by Kathleen Norris and Gareth Higgins: Published last October by Brazos Press, this excellent book comprises twelve chapters reflecting on fourteen movies (two chapters feature a complementary pair), drawing out story, insights, and meaning. It’s authored by the award-winning American spiritual memoirist and poet Kathleen Norris (Acedia and Me; The Cloister Walk; Dakota: A Spiritual Geography) and the Irish writer, peace activist, retreat leader, and festival organizer Gareth Higgins. Each chapter contains two mini-essays—one by each author, the second responding to the first, sometimes disagreeing on points—and a section of “Questions and Conversation,” which make the book especially fitting for a film/reading club. There’s also a “For Further Viewing” section in the back, with many more recommendations, several of which are new to me and which I’ve been watching (e.g., Le Havre, Love Is Strange, Patti Cake$) and really enjoying!

I so appreciate the variety of films featured in the book—which come from different eras, cultures, and genres and address different themes—and I like that the writers don’t overdetermine the films’ meanings to try to make them fit a Christian agenda, which is sometimes a trap that people writing on Christianity and film fall into (influenced partly, I’m sure, by publishers’ demands, to make the marketing easier). Norris and Higgins are simply two Christians writing about their shared love of cinema, and I had so much fun listening in on their conversations.

You may also want to check out the Substack that Norris and Higgins write together, Soul Telegram: Movies & Meaning, whose purpose is “to help people find the most life-giving movies, and to write about them as a way of reflecting on the meaning of our lives.” See also the recent Habit podcast episode “Kathleen Norris watches movies,” where Norris discusses Paterson, Babette’s Feast, After Life, and more.

+++

SONGS:

>> “Oh Mercy (Long Way to Go)” by Glen Spencer and David Gungor, 2024: Debuted by the Good Shepherd Collective on December 8, 2024. Watch on Instagram below, or this cued-up YouTube video.

>> “Sawubona” (I See You) by Jane Ramseyer Miller, 2012: The most common greeting used by Zulu people is “Sawubona,” literally meaning “I see you,” with the implication of “My whole attention is with you. I value you.” The word conveys a deep witnessing and presence, acknowledgment and connection. A standard reply is “Ngikhona,” “I am here.” This humanity-honoring exchange that occurs regularly in South Africa was set to music by the American choral director Jane Ramseyer Miller and is performed in the video below by the Justice Choir, a grassroots movement that encourages more community singing for social and environmental justice.

The song is authorized for free noncommercial use, and sheet music is available from the Justice Choir Songbook.

+++

PODCAST EPISODE: “Taylor Worley: Sacramental Eyes and Conceptual Art,” The Artistic Vision, January 31, 2025: Dr. Taylor Worley is a visiting associate professor of art history at Wheaton College, the author of Memento Mori in Contemporary Art: Theologies of Lament and Hope (Routledge, 2019), and a recipient of a grant from the Templeton Religion Trust, which he has used to research the intersection of conceptual art and Christian contemplation. He’s also become a friend of mine, as we often run into each other at conferences!

In this recent podcast interview, he talks about his most amazing teaching experience to date; helping Protestants like himself recover a sacramental ontology of the world; asking questions verbally versus aesthetically; death and mortality; what conceptual art is, and why it’s “real art”; what the esteemed Roger Scruton got wrong in his documentary Why Beauty Matters; the “Art of Attention” study he conducted with a psychophysiology colleague in the modern wing of the Art Institute of Chicago (which I participated in! here’s one of the three pieces I was tasked with looking at for five straight minutes while hooked up to a heart-rate monitor); and why artists inspire him.

+++

LECTURE: “Spirituality and Art in the Twenty-First Century” by Aaron Rosen: For its fourth annual keynote on October 23, 2024, the MSU (Michigan State University) Foglio Speaker Series on Spirituality hosted Dr. Aaron Rosen, a writer, curator, and educator on religion and the arts. He is a practicing agnostic Jew married to an Episcopal priest and the author of Art and Religion in the 21st Century (Thames & Hudson, 2015). His presentation is so well-structured and spotlights a vast range of artworks! It starts at 5:05 of the video below; the Q&A is not included.

In the talk, Rosen explores how art can facilitate or exemplify four spiritual states:

- Attention

– Simplicity

– Repetition

– Memory - Wonder

– The Uncanny

– Technological Sublime

– Sublime Silence

– Darkness

– Ecological Lament

– Ecological Hope - Care

– Resilience

– Replenishment

– Maintenance

– Recognition - Belonging

– Homecoming

– Pilgrimage

– Sanctuary

– Sharing Sacred Space

+++

VIDEO INTERVIEW: “VCS Creative Conversations: Ben Quash with Steve Reich”: “This film continues our series of ‘Creative Conversations’. In these conversations, living artists working in a variety of different artistic media discuss how the Bible and its legacies of visual and theological interpretation operate as a vital resource for their own creativity. In this film, VCS [Visual Commentary on Scripture] Director Ben Quash interviews the legendary American contemporary composer Steve Reich. They discuss the profound role of the Bible in transforming both the subject matter and the style of Reich’s music, reflecting especially on his settings of the Abraham story, the episode of Jacob’s ladder, and texts from the Psalms.”