Watch therefore: for ye know not what hour your Lord doth come.

—Matthew 24:42 (KJV)

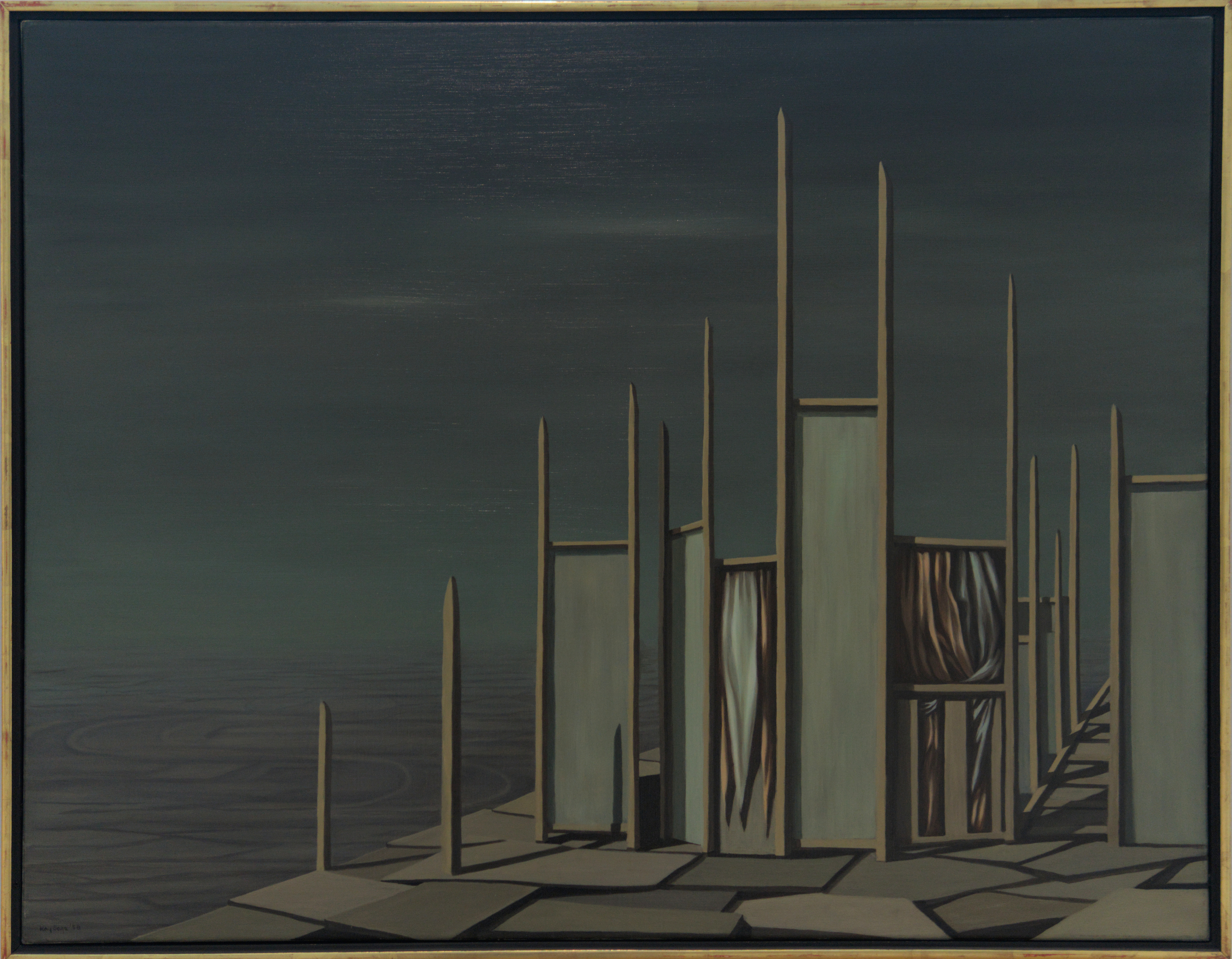

LOOK: Quote-Unquote, Hyphen, and The Point of Intersection by Kay Sage

There’s a wistful quality to the paintings of the midcentury American surrealist artist Kay Sage [previously], which often feature tenuous, draped structures and a distant light in the vast dark. The first work of hers I saw in person was Quote-Unquote, which shows a ragged, exposed architectonic form—is it fallen into disrepair, or incomplete?—whose vertical wood beams pierce the dreary gray sky.

The museum label at the Wadsworth Atheneum reads in part: “Sage’s later paintings featured vertical architectural structures, such as walls and scaffolding, set in otherwise deserted landscapes. These inanimate forms were often draped with plain fabric, as if to suggest a human presence or absence.” The title Quote-Unquote provides little interpretive help. What is being quoted here? Is irony intended?

Painted the same decade, Sage’s Hyphen shows a towering structure of open doors and windows.

And The Point of Intersection shows a series of wooden boards and frames standing, slightly diagonal to the viewer, on a ground that recedes into infinity. In the bottom left corner a rumpled sheet or garment lies on a squat platform.

Is the “intersection” of the title between time and eternity, or . . . ?

LISTEN: “Not Knowing When the Dawn Will Come” | Words by Emily Dickinson, ca. 1884 | Music by Jan Van Outryve, 2018 | Performed by Naomi Beeldens (voice) and Jeroen Malaise (piano) on Elysium, Emily Dickinson Project, 2018

Not knowing when the Dawn will come,

I open every Door,

Or has it Feathers, like a Bird,

Or Billows, like a Shore –

This is one of twelve musical settings of Dickinson poems for piano and voice by the Belgian composer Jan Van Outryve. It’s sung by soprano Naomi Beeldens, with Jeroen Malaise on keys.

I’ve always read “Not knowing” as an Advent poem, as promoting a posture of readiness for the coming of Christ—he who is, as we call out in the O Antiphons of late Advent, our Oriens, Rising Sun, Dayspring. Will he come softly, rustling, avian-like, or will he come crashing onto earth’s shore like a wave?

Expecting Dawn’s imminent arrival, the speaker of the poem opens every door, welcoming its light.

(Related posts: https://artandtheology.org/2022/12/14/advent-day-18-will-there-really-be-a-morning/; https://artandtheology.org/2022/12/15/advent-day-19-healing-wings/)

From Augustine (Confessions) to Teresa of Ávila (The Interior Castle), the picture-making nuns of St. Walburga’s Abbey in Eichstätt to C. S. Lewis (Mere Christianity), the human heart has long been compared to a house. To open the windows or doors of the heart to Christ is to invite him to come in and dwell there and to transform the place.

Advent commemorates three comings of Christ: his coming in “history, mystery, and majesty,” as one priest put it. That is, Christ’s coming (1) as a babe in Bethlehem, (2) in the Spirit, to convert, illuminate, equip, and console, and in the bread and wine of the Eucharist, and (3) at the end of time.

Have you opened every door to him? Do you eagerly expect him to arrive—this Christmas (are you telling, singing, enacting the story of his nativity?); into your struggles and brokenness, to companion you and to heal and strengthen; and again on earth, to unite it with heaven and establish, fully and finally, his universal reign?

This is the first post in a daily Advent and Christmastide series that will extend to January 6. I hope you follow along!